Space Physics: A definitional perspective

I was trained as a space physicist. My PhD work was rooted in space physics, with a clear emphasis on space plasma physics. That background still shapes how I think about physical systems, not only in space but more generally. At the same time, I have never understood space physics as being synonymous with plasma physics alone. Plasma processes form its dynamical core, but the discipline itself is broader in scope, historically grounded in geophysics and conceptually extending planetary physics beyond Earth.

Schematic of Earth’s magnetosphere, with the solar wind flows from left to right. Space physics studies the interacttion between charged particles, electromagnetic fields, and planetary bodies in space environments. However, its scope extends beyond plasma physics alone, encompassing neutral atmospheres, planetary magnetism, and the coupling between solid bodies and their space environment. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Space physics did not emerge from astronomy looking outward into deep space. It emerged from geophysics looking upward. In this post, I want to outline how I see space physics as a discipline, its relationship to plasma physics, planetary science, and astrophysics, and how my own training shaped my perspective.

From geomagnetism to space

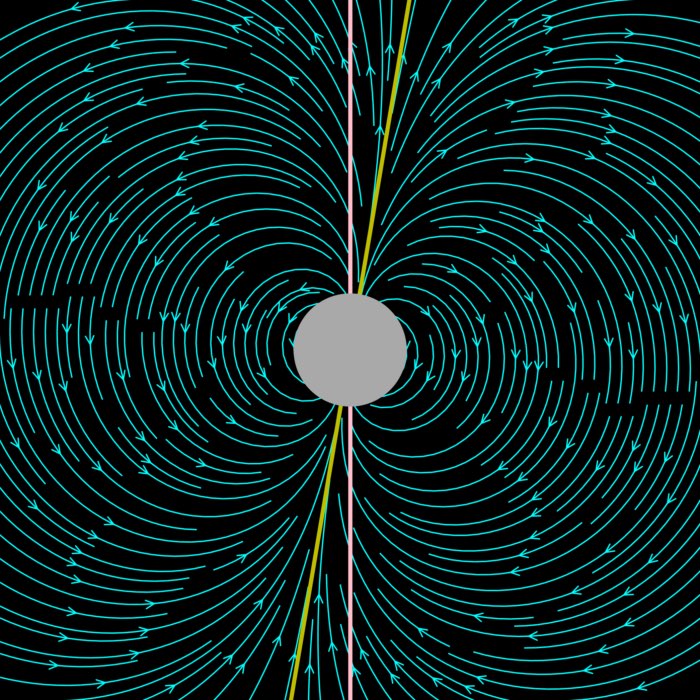

The historical roots of space physics lie in the study of Earth’s magnetic field, aurorae, and the electrically active upper atmosphere. Long before the first satellite, scientists were already dealing with phenomena that could not be explained within classical atmospheric physics. Magnetic storms, compass deviations, and polar lights were clearly linked to processes beyond the neutral atmosphere, yet intimately coupled to Earth as a physical body.

Artist’s impression of solar wind flow around Earth’s magnetosphere. The solar wind is a continuous outflow of ionized plasma from the Sun that interacts with planetary magnetic fields. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

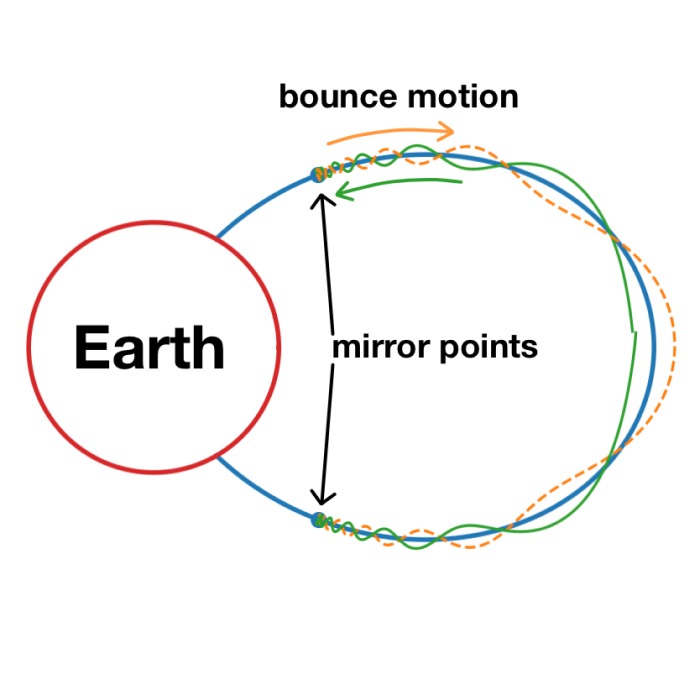

This is why the intellectual lineage of space physics runs through geomagnetism, atmospheric electricity, and ionospheric physics rather than classical astronomy. The central questions were not about distant objects, but about interactions: how solar activity affects Earth’s magnetic environment, how charged particles move along magnetic field lines, and how energy enters and propagates through coupled geospace systems.

In this sense, space physics can be understood as an extension of geophysics. It applies the same physical thinking to regions where neutral fluids give way to ionized, magnetized matter.

Plasma physics as the dynamical core

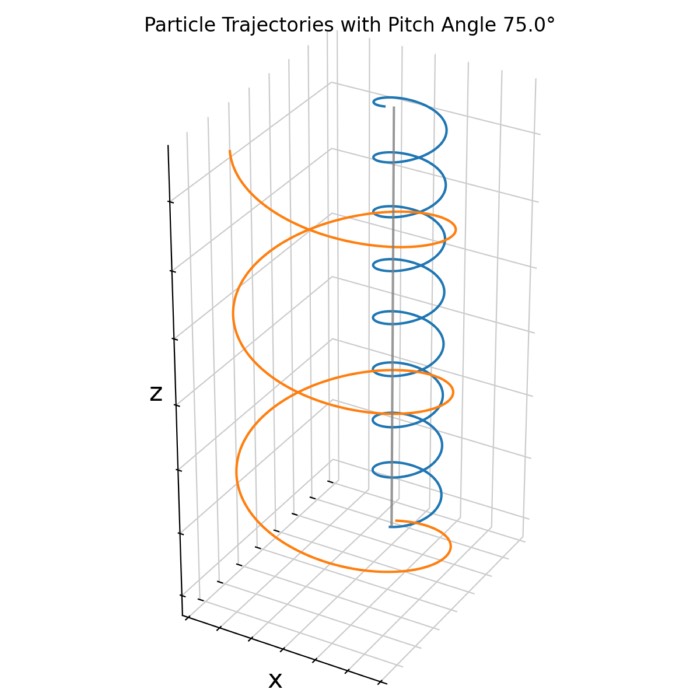

The prominence of plasma physics in space physics is not ideological, but physical. Most of near-Earth space, the heliosphere, and the environments of many planets and moons are plasma dominated. Charged particles, electromagnetic fields, and collective behavior define the dynamics.

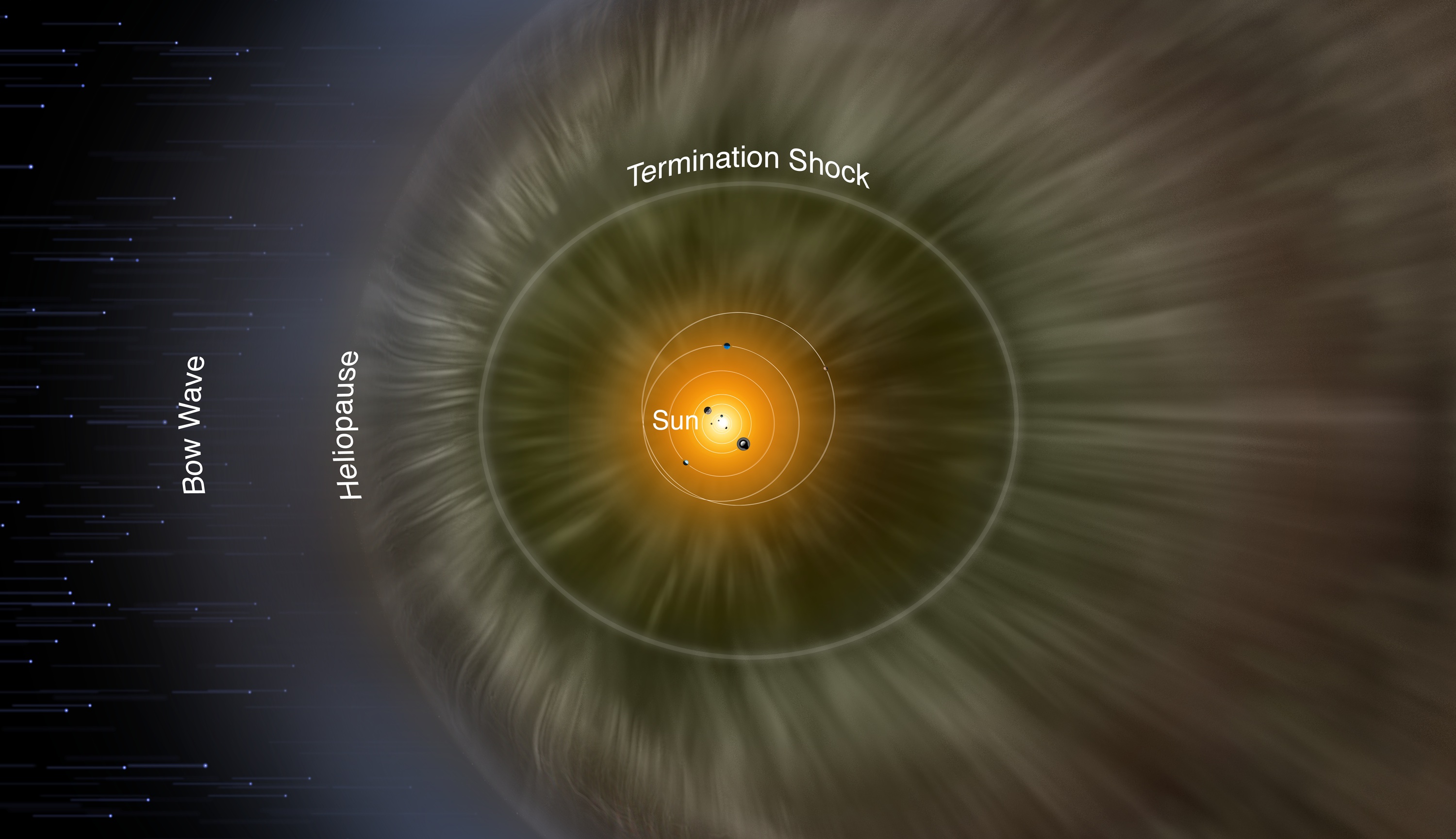

The heliosphere under the influence of the interstellar medium with the orbits of the planets and Pluto. It is bounded by the heliopause. The extent to which it is deformed and has a long “heliotail” is unclear. The interstellar gas probably accumulates to form a bow wave, but not a bow shock. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

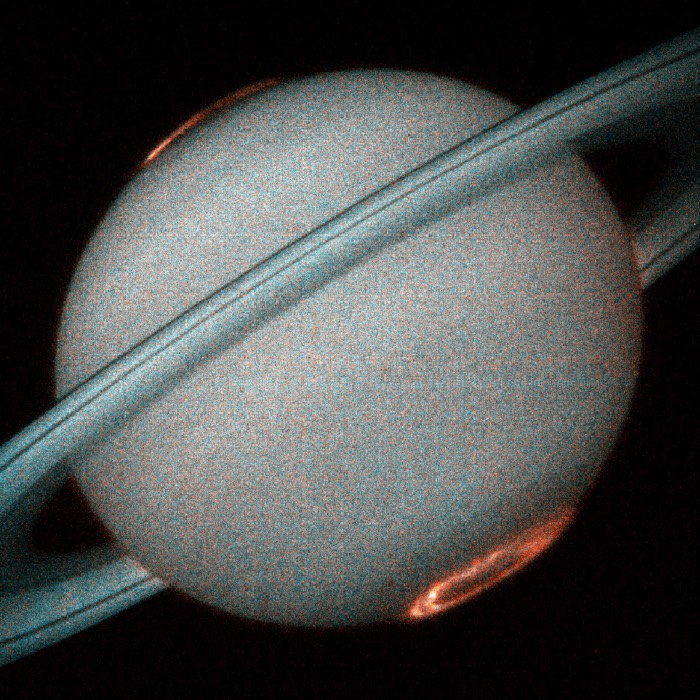

My own work was rooted in these processes. During my training, I focused on the motion of charged particles in magnetic fields, on plasma waves, and on auroral phenomena. My master’s work dealt with ion cyclotron waves in the vicinity of Saturn’s moons, while my PhD focused on the aurora of Ganymede, a system where plasma dynamics, magnetic topology, and planetary boundary conditions intersect in a particularly clear way. These topics naturally fall under the umbrella of space plasma physics, and they shaped how I learned to think about space environments as physical systems.

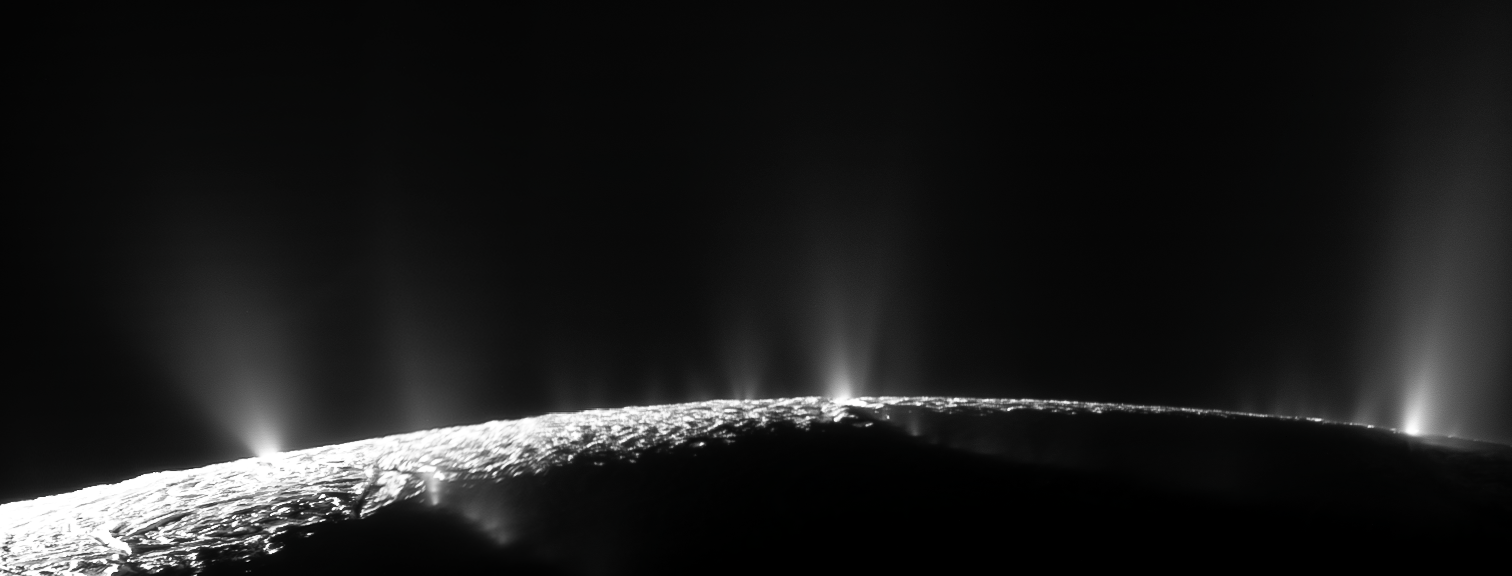

A panorama of Enceladus’s plumes taken by the Cassini spacecraft. The interaction between Enceladus’s plumes and Saturn’s magnetospheric plasma creates a complex plasma environment that is a key focus of space physics research. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 2.0).

At the same time, it is important not to confuse a dominant physical framework with the full scope of the discipline. Space physics also includes neutral atmospheres, radiation belts, energetic particles, planetary magnetic fields, and the coupling between solid bodies and their surrounding space environment. Plasma physics explains much of the dynamics, but it does not exhaust the subject.

Left: Magnetic field of the Jovian satellite Ganymede, which is embedded into the magnetosphere of Jupiter. Closed field lines are marked with green color. Ganymede is, so far, the only moon in the solar system known to possess a substantial intrinsic magnetic field. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: Aurorae on Ganymede. Due to the interaction with Jupiter’s magnetospheric plasma, Ganymede exhibits auroral emissions similar to those on Earth. From the shifting of the auroral belts, space physics is able to infer the presence of a subsurface ocean beneath Ganymede’s icy crust. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Space physics and planetary science

Space physics and planetary science are not competing disciplines. They intersect.

Planetary science addresses the full physical reality of planets and moons, including geology, geochemistry, atmospheres, and internal structure. Space physics becomes relevant wherever these bodies interact with their space environment through magnetic fields, ionospheres, or plasma flows.

The Sun, planets, moons, and dwarf planets (true color, size to scale, distances not to scale). Space physics intersects with planetary science wherever planetary bodies interact with their space environment through magnetic fields, ionospheres, or plasma flows. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

The solar wind interaction with Mars, the intrinsic magnetosphere of Ganymede, or the plasma torus around Io are not marginal topics. They are central examples of how planetary bodies and space environments form coupled systems. In that sense, space physics generalizes geophysics to other celestial bodies.

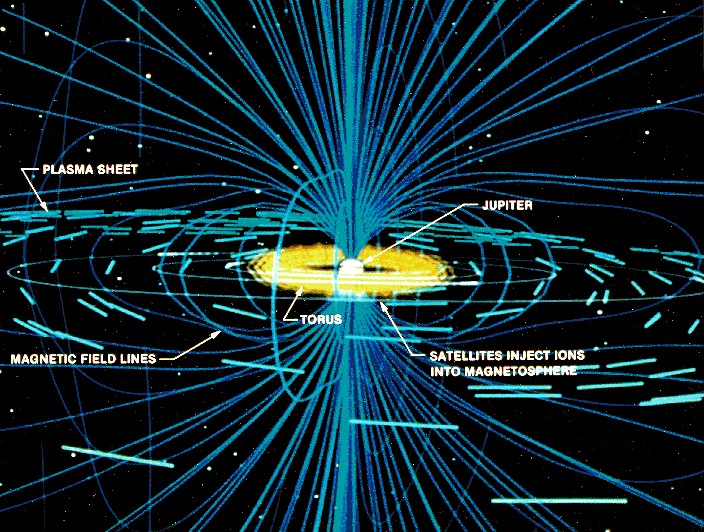

Io’s interaction with Jupiter’s magnetosphere. The Io plasma torus, a ring of ionized particles originating from Io’s volcanic activity, here shown in yellow, is a prime example of how planetary bodies and space environments form coupled systems. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

This perspective was always natural to me. Studying Earth’s magnetosphere and ionosphere inevitably raises the question of how similar processes operate elsewhere. The physics does not change, only the boundary conditions do.

Relationship to astrophysics

Space physics is often grouped together with astrophysics, but the overlap is limited. Astrophysics is primarily concerned with gravitationally bound systems and relies heavily on remote sensing. Space physics is fundamentally local and in-situ. It measures fields, particles, and distribution functions directly, often resolving temporal and spatial variability that astrophysical observations must average over.

The planetary nebula Messier 57, also known as the Ring Nebula, in the constellation Lyra (NGC 6720, GC 4447). Astrophysics often deals with gravitationally bound systems and vast distances, while space physics focuses on local, in-situ measurements within our solar system, with focus on planetary environments. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

There is increasing conceptual exchange, especially where plasma processes dominate in astrophysical settings. Still, the methodological DNA of space physics remains distinct. Its closest relative is not stellar astrophysics, but geophysics and fluid dynamics.

Beyond the solar system

Operationally, space physics has focused on the solar system, simply because this is where in-situ measurements are possible. Conceptually, the field is not limited to it. The same physical processes govern stellar winds, astrospheres, and exoplanetary environments.

Artist impression of the magnetic field around Tau Boötis b detected in 2020. Exoplanets interact with their stellar environment through plasma processes similar to those studied in our solar system. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

As observational techniques evolve, the boundary between space physics and astrophysical plasma physics will likely shift. The discipline is defined not by distance, but by the physics of coupled plasma–field systems.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST), as seen from the space shuttle Discovery during its second servicing mission. One source of data for space physics research are space-based observatories like HST, which can capture auroral emissions and other phenomena in planetary atmospheres. Other data come from in-situ measurements by spacecraft exploring planetary magnetospheres and the solar wind. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 2.0).

Closing perspective

Looking back, my training in space physics shaped how I approach complex systems more generally. The field sits at an intersection: between Earth and space, between plasma physics and planetary science, between theory and measurement. It studies systems that are inherently nonlinear, multiscale, and driven far from equilibrium.

Space plasma physics was my entry point, and it remains a central pillar. But space physics, as I understand it, is larger than that. It is geophysics extended into space, applied wherever electromagnetic processes link celestial bodies to their environment.

That perspective still informs how I think about physics today, even when working far outside the original domain of my PhD.

Historical overview of space physics

Out of a whim, I once compiled a timeline of key milestones in space physics. It highlights how the field evolved from early observations of aurorae and geomagnetic phenomena to the modern era of space missions and plasma theory. I think, it nicely illustrates the interplay between theory, observation, and technological advancement that characterizes space physics. Be aware, the list anything than complete. I will update it over time. If you have suggestions for additions, please let me know in the comments below.

| Year | Theory | Observation | Mission | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 BCE | ✗ | Earliest written records of auroral phenomena in China | ||

| ~1300 BCE | ✗ | Bronze Age depictions of solar or celestial events in Europe | ||

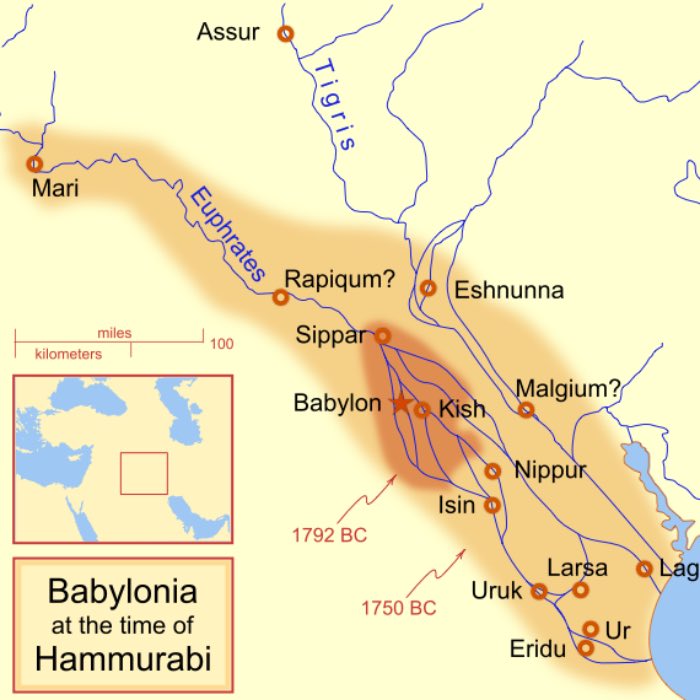

| ~800 BCE | ✗ | Babylonian eclipse records | ||

| ~600 BCE | ✗ | Thales of Milet and early eclipse prediction | ||

| 450 BCE | ✗ | Magnetic lodestone alignment observed in China | ||

| 400 BCE | ✗ | Empedocles and Plato discuss first speculative theories about light and radiation | ||

| ~300 BCE | ✗ | Aristotle’s natural philosophy explanation of aurora | ||

| 28 BCE | ✗ | First recorded sunspots | ||

| 1st c. CE | ✗ | Plinius the Older talks about magnetic effects and sunspots in his Naturalis historia | ||

| ~1000 | ✗ | Use of floating magnetic compasses in China for navigation | ||

| 1187 | ✗ | Alexander Neckam describes fixed magnetic compass in Europe | ||

| 1269 | ✗ | Petrus Peregrinus’ Epistola de magnete, systematic magnet theory | ||

| 1600 | ✗ | Gilbert’s De Magnete, foundation of geomagnetism | ||

| 1610 | ✗ | Telescopic sunspot observations by Galileo | ||

| 1620ies | ✗ | Christoph Scheiner and Johannes Fabricius document regularly the tracks of sunspots (first sunspots maps) | ||

| 1635 | ✗ | Descartes proposes mechanical explanation of aurorae | ||

| 1705 | ✗ | Edmond Halley discovers the periodic return of a comet, that later bears his name; marks the beginning of cometary astronomy | ||

| 1716 | ✗ | Halley links aurorae to geomagnetic processes | ||

| 1770 | ✗ | Global auroral event, early link to solar activity | ||

| 1785 | ✗ | Charles-Augustin de Coulomb describes the inverse quadratic las of magnetic forces, which become the fundamental base for the electromagnetic theory | ||

| 1800 | ✗ | Herschel discovers infrared radiation in the solar spectrum | ||

| 1804 | ✗ | Alexander von Humboldt observes aurorae during his expeditions; he later creates geomagnetic maps | ||

| 1811 | ✗ | The Giant Comet of 1811 observed worldwide; important event in cometary astronomy and systematical cometary classification | ||

| 1820 | ✗ | Hans Christian Ørsted discovers the connection between electric current and magnetism, marking the beginning of electrodynamics | ||

| 1821 | ✗ | Michael Faraday begins experiments on electromagnetic induction | ||

| 1830s | ✗ | Gauss and Weber develop the first worldwide network for systematic measurements of Earth’s magnetic field | ||

| 1839 | ✗ | Gauss shows dominant geomagnetic field originates inside Earth | ||

| 1843 | ✗ | Discovery of the solar sunspot cycle by Schwabe | ||

| 1851 | ✗ | First photographic solar eclipse, coronal structures observed | ||

| 1856 | ✗ | Wilhelm Eduard Weber and Rudolf Kohlrausch determine the speed of light as a link between electric and magnetic interaction | ||

| 1856 | ✗ | Wilhelm Eduard Weber and Rudolf Kohlrausch determine the speed of light as a link between electric and magnetic interaction | ||

| 1859 | ✗ | Carrington event, extreme geomagnetic storm | ||

| 1860 | ✗ | First systematic map of auroral phenomena; Maxwell formulates kinetic gas theory (later extended by Boltzmann) | ||

| 1864 | ✗ | Maxwell’s electromagnetic field theory | ||

| 1865 | ✗ | James Clerk Maxwell fully unifies electricity, magnetism, and light in Maxwell’s theory | ||

| 1867 | ✗ | Ångström shows aurorae are self-luminous gas | ||

| 1895 | ✗ | Hendrik Lorentz develops an electron model of the ether, forming the basis of classical plasma theory | ||

| 1896 | ✗ | Birkeland’s auroral electron hypothesis | ||

| 1905 | ✗ | Einstein explains the photoelectric effect, initiating the quantum understanding of electromagnetic radiation | ||

| 1918 | ✗ | Larmor motion of charged particles | ||

| 1926–1930 | ✗ | Appleton–Hartree theory of ionospheric wave propagation | ||

| 1930ies | ✗ | Emergence of magnetohydrodynamics | ||

| 1931 | ✗ | Jansky discovers cosmic radio emission | ||

| 1933 | ✗ | Schrödinger and Dirac generalize the quantum-mechanical description of electron motion in fields | ||

| 1942 | ✗ | First systematic radio observation of the Sun (solar radio burst) | ||

| 1942 | ✗ | Alfvén waves proposed | ||

| 1947 | ✗ | Ionosphere experimentally confirmed (Appleton) | ||

| 1950 | ✗ | Enrico Fermi formulates stochastic particle acceleration (Fermi acceleration), foundational for cosmic-ray physics | ||

| 1951 | ✗ | Start of continuous global geomagnetic monitoring | ||

| 1957 | ✗ | Parker solar wind theory | ||

| 1957 | ✗ | Sputnik 1, start of space age | ||

| 1957–58 | ✗ | International Geophysical Year establishes space-era geophysics | ||

| 1958 | ✗ | Discovery of Van Allen belts by Explorer 1 | ||

| 1958 | ✗ | Parker describes the spiral structure of the interplanetary magnetic field (Parker spiral) | ||

| 1959 | ✗ | Lunik 1 (USSR) detects the solar wind and performs the first lunar flyby | ||

| 1960 | ✗ | James Dungey describes his theory on magnetic reconnection and the open magnetosphere model | ||

| 1960 | ✗ | First satellite EUV image of the solar corona obtained with Aerobee | ||

| 1962 | ✗ | Mariner 2 (USA) becomes the first interplanetary probe and measures the solar wind during a Venus flyby | ||

| 1963 | ✗ | Eugene Parker reformulates the continuous solar wind as a solution of the hydrodynamic equations | ||

| 1963 | ✗ | Sagdeev potential extends nonlinear plasma wave theory | ||

| 1965 | ✗ | Akasofu formulates magnetospheric substorm theory | ||

| 1965 | ✗ | Axford–Hines model explains plasma flows in the magnetosphere | ||

| 1965 | ✗ | Venera 3 (USSR) becomes the first spacecraft to reach Venus (impact) | ||

| 1966 | ✗ | Solar wind compression of Earth’s magnetosphere modeled | ||

| 1967 | ✗ | Discovery of pulsars by Bell and Hewish, providing indirect evidence for extremely strong magnetic fields | ||

| 1970 | ✗ | Hannes Alfvén receives the Nobel Prize for foundational work in magnetohydrodynamics (Alfvén waves) | ||

| 1970 | ✗ | OGO-5 observes continuous ultraviolet solar flares for the first time | ||

| 1971 | ✗ | Mars 3 (USSR) achieves the first soft landing on Mars | ||

| 1973 | ✗ | Pioneer 10 (USA) performs the first Jupiter encounter and crosses the asteroid belt | ||

| 1973 | ✗ | Kennel and Petschek formulate the theory of standing Alfvén waves in the magnetosphere | ||

| 1973 | ✗ | Skylab Apollo Telescope provides the first UV and X-ray images of the solar corona | ||

| 1974 | ✗ | Helios 1 probe explores for the first time the solar wind in the inner heliosphere | ||

| 1976 | ✗ | Drift models of the plasmapause by Goldstein et al. | ||

| 1977 | ✗ | Voyager 1 & 2 exploration of outer planets | ||

| 1978 | ✗ | Pioneer Venus (USA) Orbiter and Lander investigate the Venusian atmosphere | ||

| 1981 | ✗ | Global magnetotail reconnection and plasma transport by Vasyliunas | ||

| 1983 | ✗ | ISEE-3/ICE (USA) is redirected to perform the first comet encounter | ||

| 1990s | ✗ | Global MHD simulations of magnetospheres | ||

| 1990 | ✗ | Ulysses (ESA/NASA) performs the first polar observations of the Sun | ||

| 1990 | ✗ | Hubble Space Telescope (HST) begins revolutionary optical observations of the Universe | ||

| 1991 | ✗ | Yohkoh (Japan/USA) conducts the first long-term X-ray observations of the Sun | ||

| 1995 | ✗ | SOHO (ESA/NASA) begins continuous solar observations from the L1 Lagrange point | ||

| 1997 | ✗ | Mars Pathfinder (USA) deploys the first Mars rover, Sojourner | ||

| 1997 | ✗ | Cassini-Huygens (NASA/ESA) launches toward Saturn, later delivering the Huygens lander to Titan | ||

| 1998 | ✗ | Deep Space 1 (USA) demonstrates ion propulsion and encounters an asteroid and a comet | ||

| 2000s | ✗ | Fully global MHD simulations of the magnetosphere (e.g. BATS-R-US, OpenGGCM) | ||

| 2001 | ✗ | Cluster mission and multi-point plasma diagnostics | ||

| 2001 | ✗ | NEAR Shoemaker (USA) performs the first landing on an asteroid (Eros) | ||

| 2002 | ✗ | RHESSI (NASA) observes high-energy X-ray and gamma-ray emission from solar flares | ||

| 2004 | ✗ | Rosetta (ESA) enters orbit around comet 67P and deploys the Philae lander | ||

| 2004–2005 | ✗ | Cassini reaches Saturn and Huygens lands on Titan | ||

| 2006 | ✗ | STEREO (NASA) enables 3D observations of coronal mass ejections with two spacecraft | ||

| 2006 | ✗ | New Horizons (USA) begins exploration of Pluto and the Kuiper belt | ||

| 2006 | ✗ | Hinode (JAXA/NASA) provides high-resolution measurements of photospheric magnetic fields | ||

| 2007 | ✗ | Dawn (NASA) investigates the asteroids Vesta and Ceres | ||

| 2007 | ✗ | THEMIS (NASA) studies magnetospheric substorms | ||

| 2008 | ✗ | IBEX (NASA) maps the heliospheric boundary using energetic neutral atom imaging | ||

| 2009 | ✗ | SDO (NASA) delivers high-resolution observations of the solar atmosphere | ||

| 2010s | ✗ | Plasma turbulence established as a central framework for coronal heating and solar wind acceleration | ||

| 2011 | ✗ | Juno (NASA) conducts an extensive mission to Jupiter, mapping its magnetic field and polar regions | ||

| 2014 | ✗ | MAVEN (NASA) studies the interaction between the solar wind and the Martian atmosphere | ||

| 2015 | ✗ | LOFAR (Netherlands) observes solar storms and planetary aurorae using a low-frequency radio array | ||

| 2016 | ✗ | ExoMars TGO (ESA/Roscosmos) analyzes trace gases in the Martian atmosphere | ||

| 2016 | ✗ | OSIRIS-REx (NASA) returns samples from asteroid Bennu (returned in 2023) | ||

| 2018 | ✗ | Parker Solar Probe enters solar corona | ||

| 2020s | ✗ | Theories of dissipative plasma turbulence validated by Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter | ||

| 2020 | ✗ | Solar Orbiter high-resolution solar observations | ||

| 2020 | ✗ | Perseverance (NASA) deploys the Ingenuity helicopter and searches for biosignatures on Mars | ||

| 2021 | ✗ | James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observes the early Universe in the infrared | ||

| 2021 | ✗ | Lucy (NASA) begins exploration of Jupiter Trojan asteroids | ||

| 2022 | ✗ | DART (NASA) performs the first active asteroid deflection test (Dimorphos) | ||

| 2023 | ✗ | JUICE (ESA) launches to explore the Jovian moons Ganymede, Europa, and Callisto | ||

| 2024 | ✗ | Psyche (NASA) targets the metallic asteroid 16 Psyche | ||

| 2025 | ✗ | THOR (ESA) investigates turbulence and dissipation in the solar wind | ||

| 2025 | ✗ | Europa Clipper (NASA) explores Jupiter’s moon Europa with a focus on its subsurface ocean |

Thematic overview

My last posts covered topics in space physics and I will continue that series a little further. Here This post is a good opportunity, I guess, to structure the topics of space physics in general, including links to relevant posts where available.

- Plasma: Definition and Characteristics

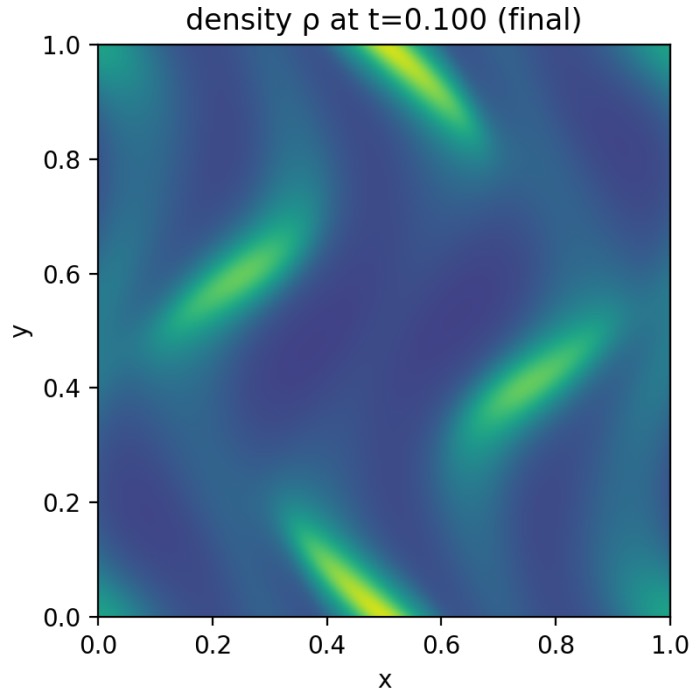

- Single-particle description of plasmas: Equation of motion, gyration, drifts

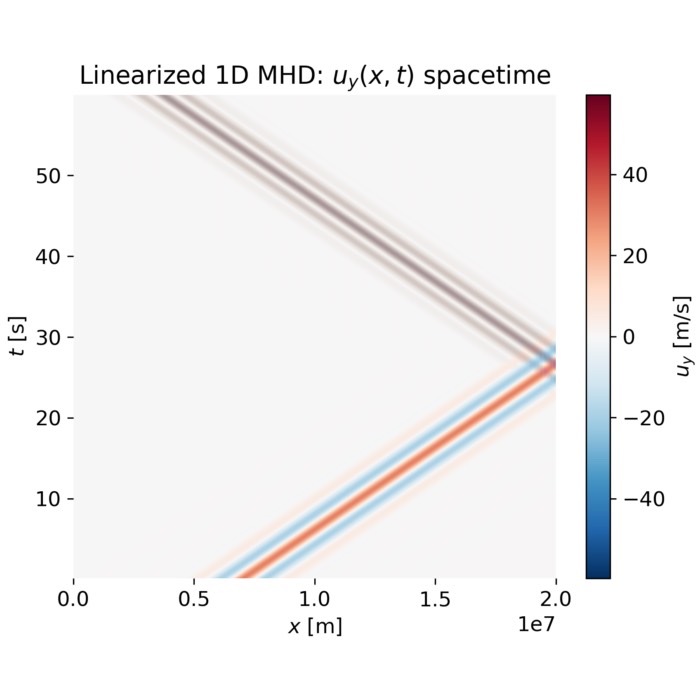

- Fluid description of plasmas: Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD), frozen-in theorem, adiabatic invariants and magnetic mirrors

- Magnetic fields in space: Earth’s dipole field, planetary magnetism

- The solar wind and the Parker spiral

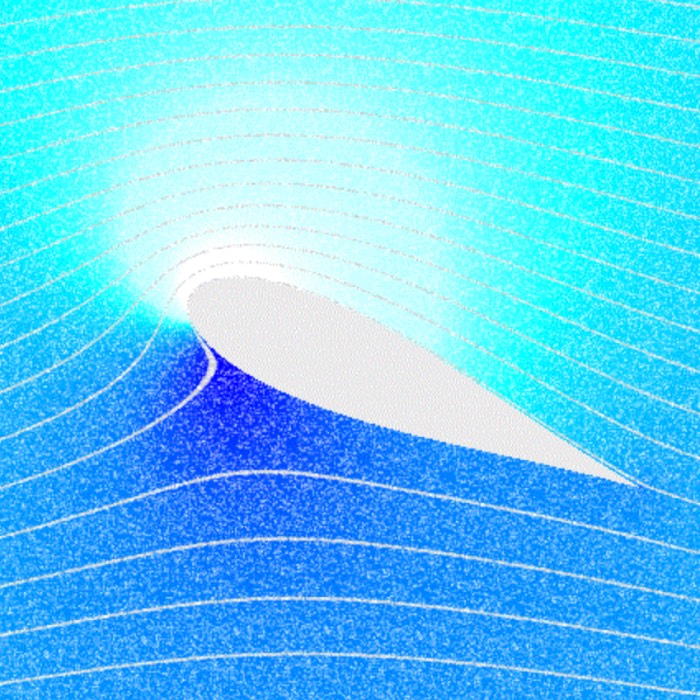

- Planetary magnetospheres: Structure, dynamics, and coupling to the solar wind

- Planetary ionospheres and atmospheres: Interaction with space environment

- Planetary aurorae

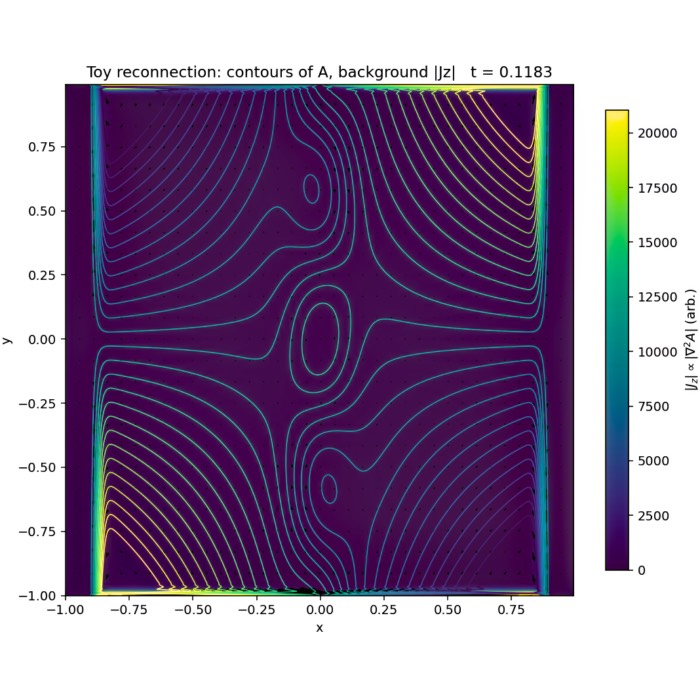

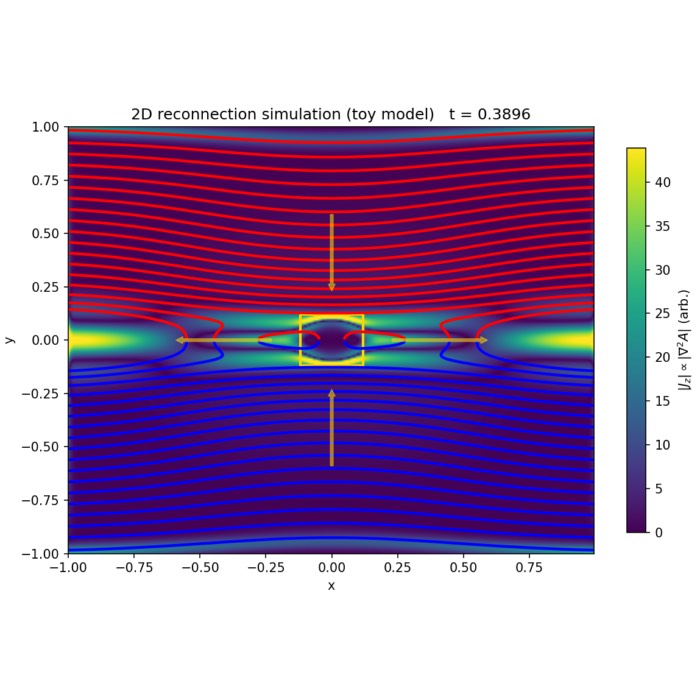

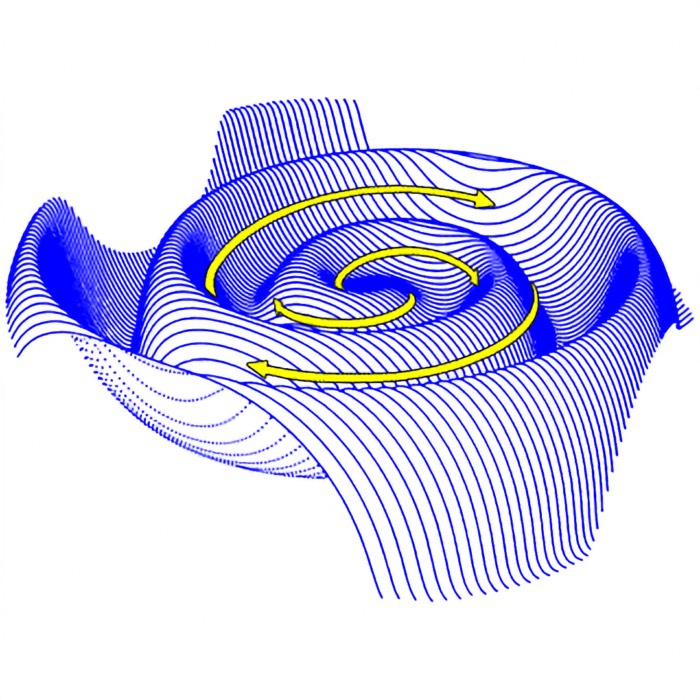

- Magnetic reconnection: Theory and applications in space plasmas

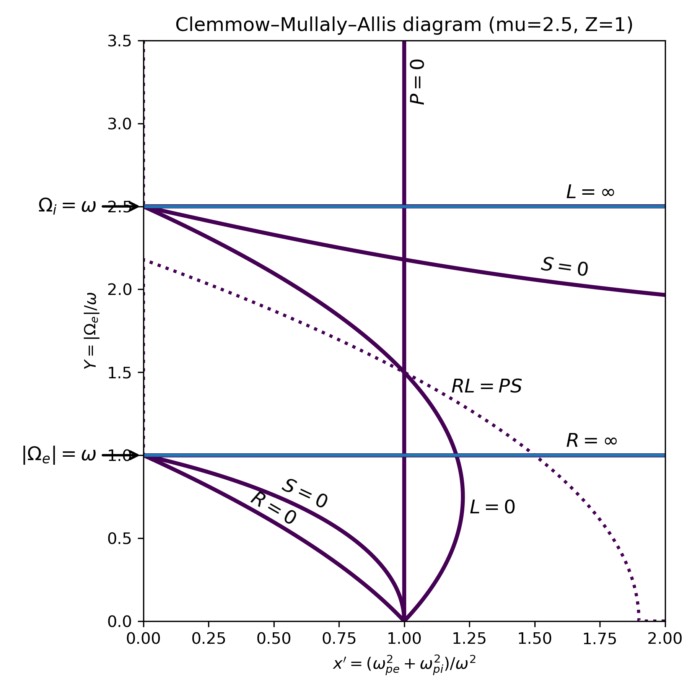

- Plasma waves and instabilities: Types (electrostatic and electromagnetic; Alfvén, whistler, magnetosonic, Langmuir, ion-acoustic), generation mechanisms, and observational signatures

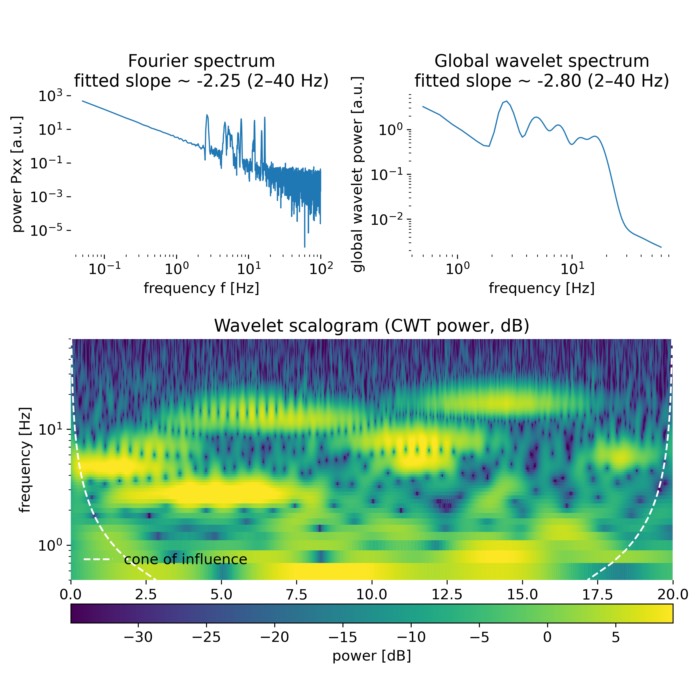

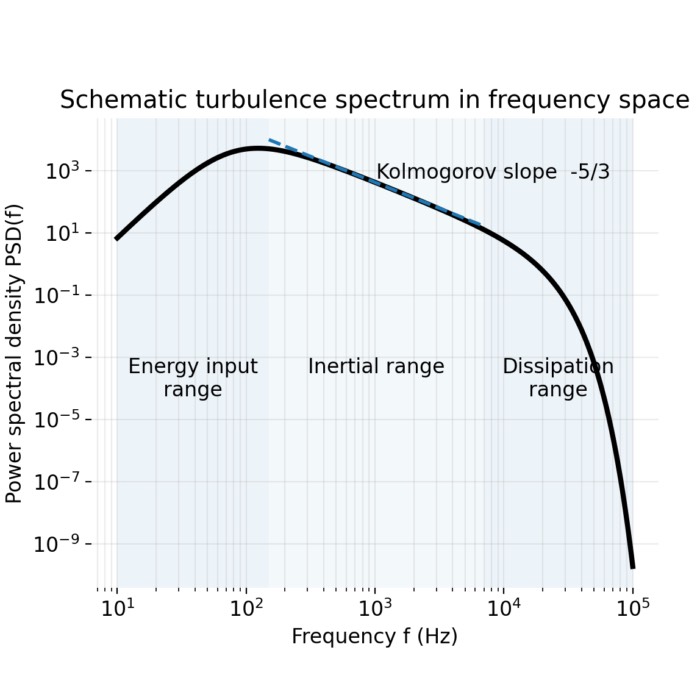

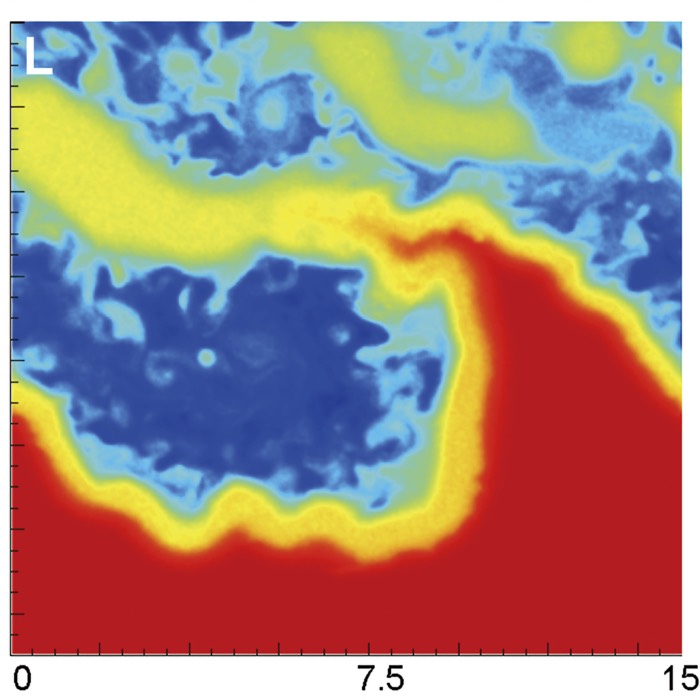

- Space plasma turbulence: Nature, scaling laws, and dissipation mechanisms

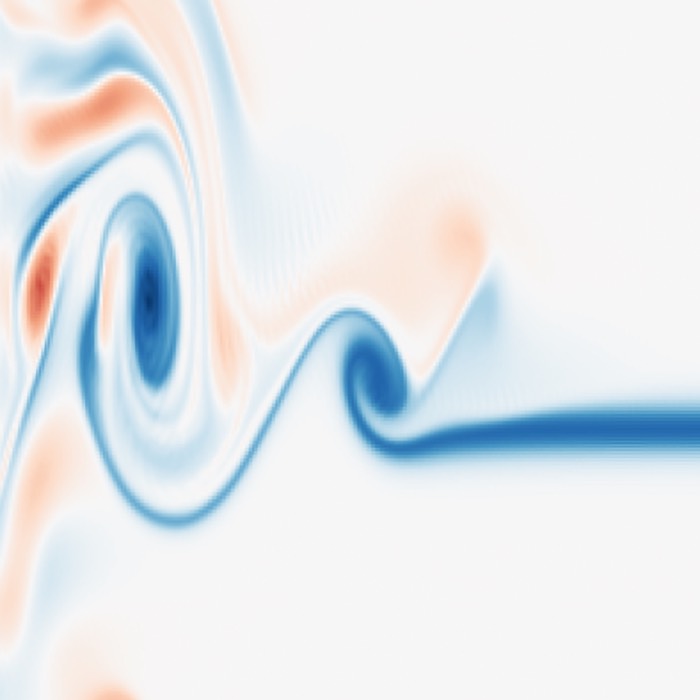

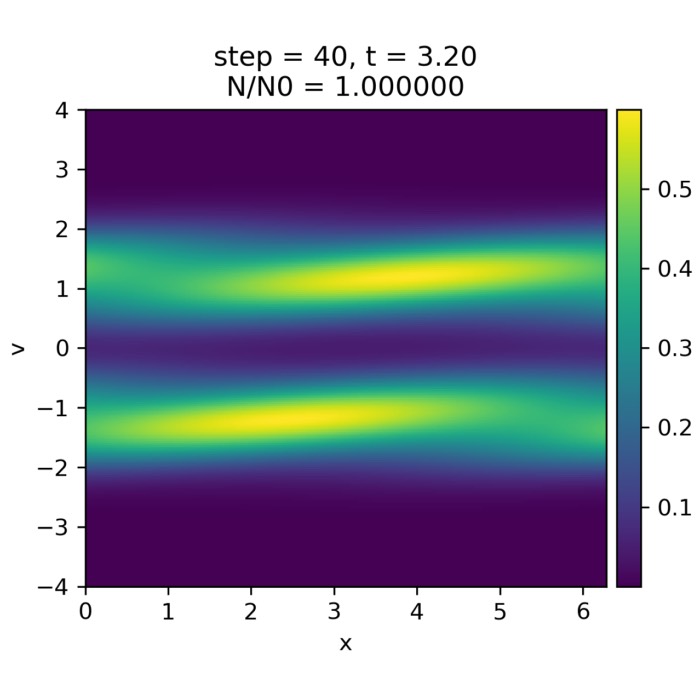

- Kinetic plasma theory: Distribution functions, Vlasov equation, wave-particle interactions

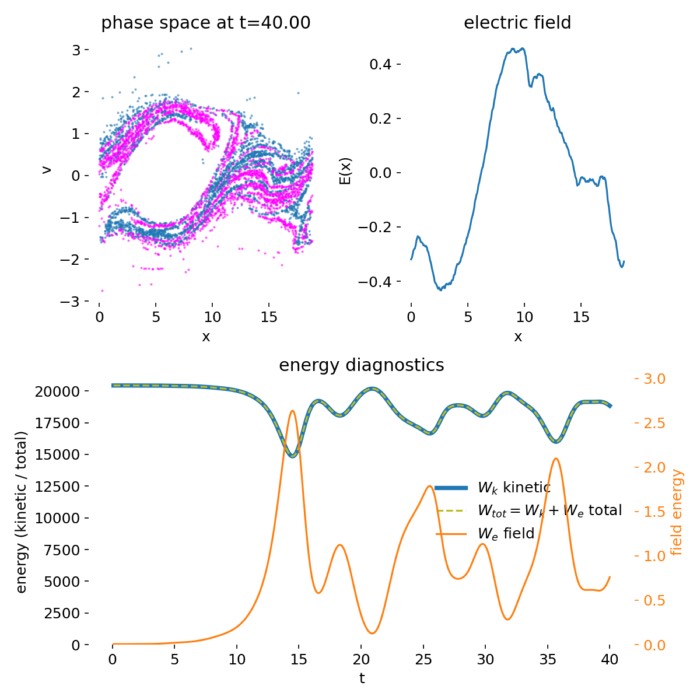

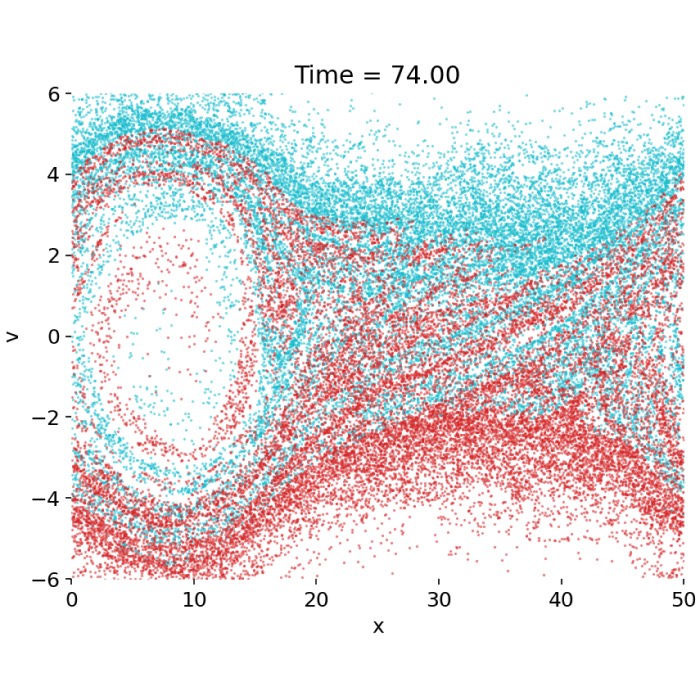

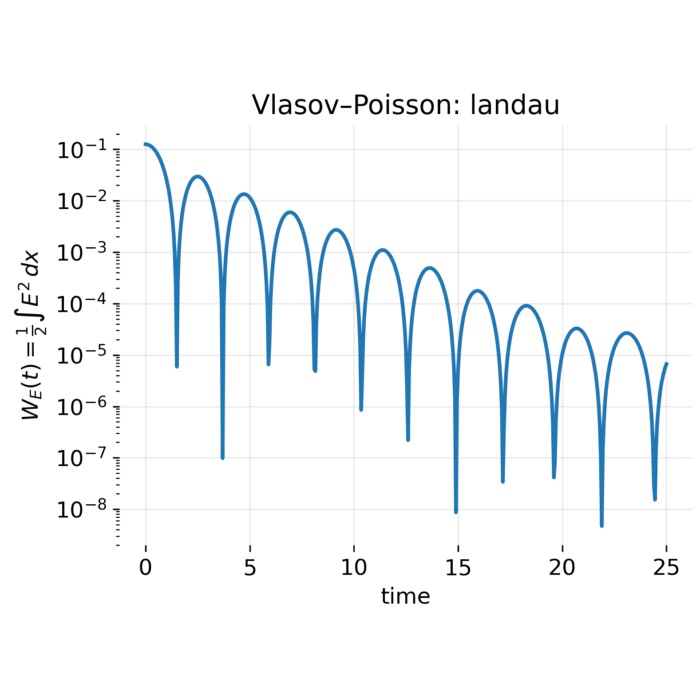

- Vlasov–Poisson dynamics: Landau damping and the two-stream instability

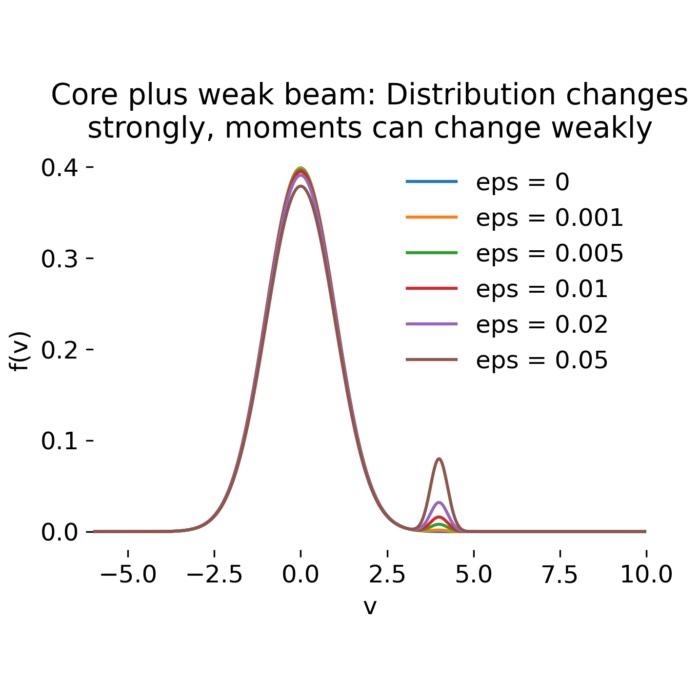

- Core plus beam distributions

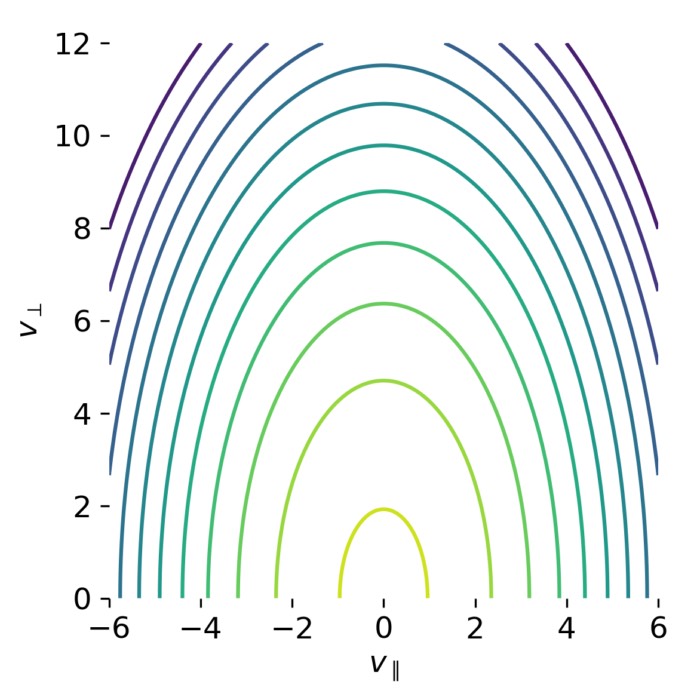

- Bi-Maxwellian distributions and anisotropic pressure

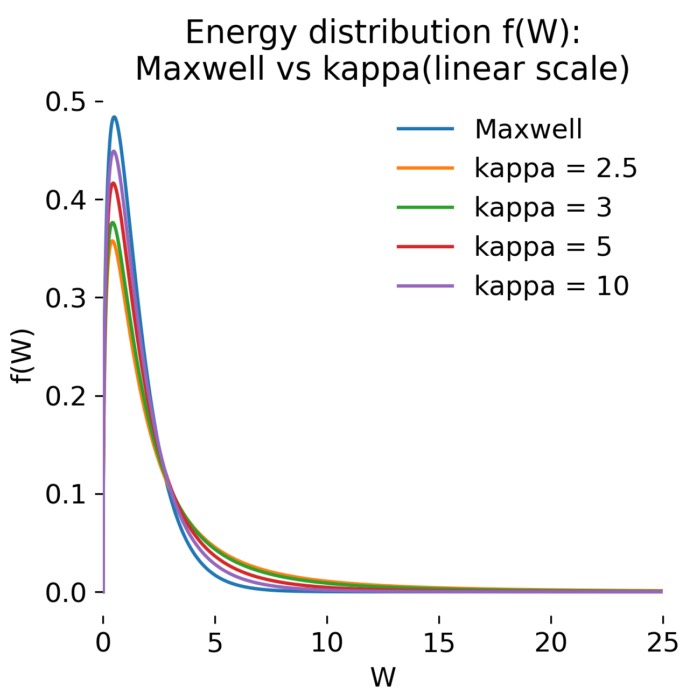

- Kappa versus Maxwell distributions: Suprathermal tails in collisionless plasmas

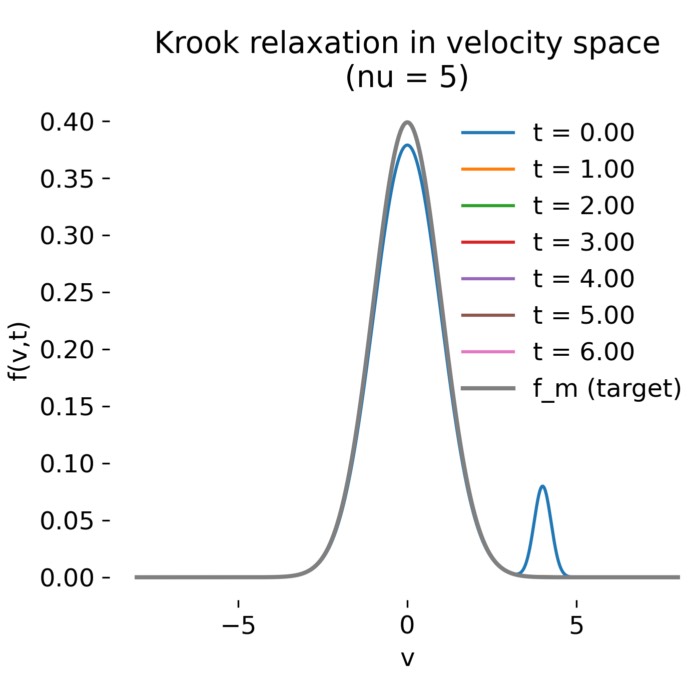

- Krook collision operator

- Particle-in-Cell methods, where different numerical techniques can be applied to solve the Vlasov equation

Update: This post was originally drafted in 2020 and archived during the migration of this website to Jekyll and Markdown. In January 2026, I substantially revised and expanded the content and decided to re-release it in an updated and technically consistent form, while keeping its original chronological context.

References and further reading

- Wolfgang Baumjohann and Rudolf A. Treumann, Basic Space Plasma Physics, 1997, Imperial College Press, ISBN: 1-86094-079-X

- Treumann, R. A., Baumjohann, W., Advanced Space Plasma Physics, 1997, Imperial College Press, ISBN: 978-1-86094-026-2

- J. A. Bittencourt, Fundamentals of Plasma Physics, 2004, Springer, ISBN: 978-0-387-20975-3

- Cravens, T. E., Physics of Solar System Plasmas, 1997, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521611947

- Bagenal, F., Dowling, T. E., McKinnon, W. B. (eds.), Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521035453

- Dougherty, M. K., Esposito, L. W., Krimigis, S. M., Gombosi, T. I., Amstrong, T. P., Arridge, C. S., Khurana, K. K., Krimigis, S. M., Krupp, N., Persoon, A. M., & Thomsen, M., Saturn from Cassini-Huygens, 2009, Springer, ISBN: 978-1402092169

- Kivelson, M. G., Russell, C. T. (eds.), Introduction to space physics, 1995, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521457149

comments