Sati: A historical and philosophical analysis of mindfulness in Buddhism

The concept of mindfulness has gained immense popularity in contemporary Western societies, often promoted as a secular practice for stress reduction, emotional regulation, and enhanced cognitive performance. While the modern notion of mindfulness is largely derived from Buddhist traditions, the term “mindfulness” is a translation of the Pāli word sati, which occupies a more complex and multifaceted role within Buddhist thought and practice. In this post, we examine sati from a historical, philosophical, and doctrinal perspective, tracing its origins and development within Buddhist contexts, and critically analyze how it differs from or aligns with modern interpretations.

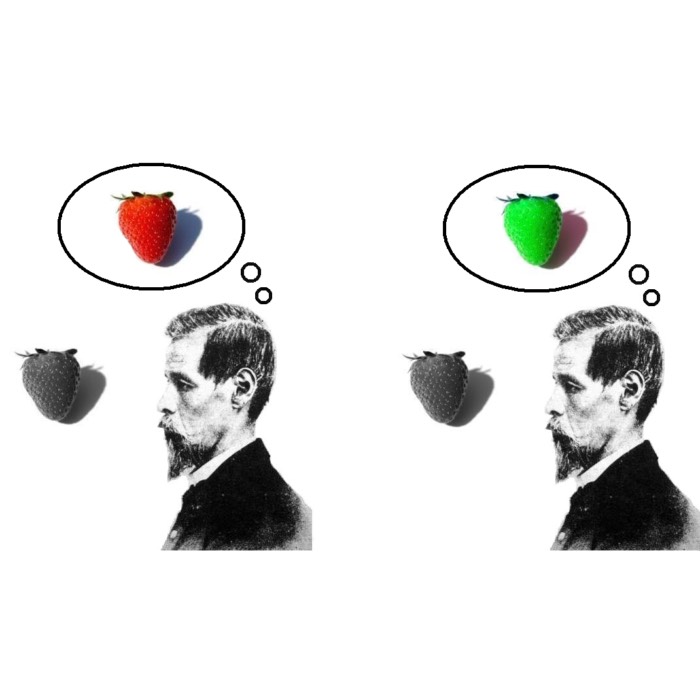

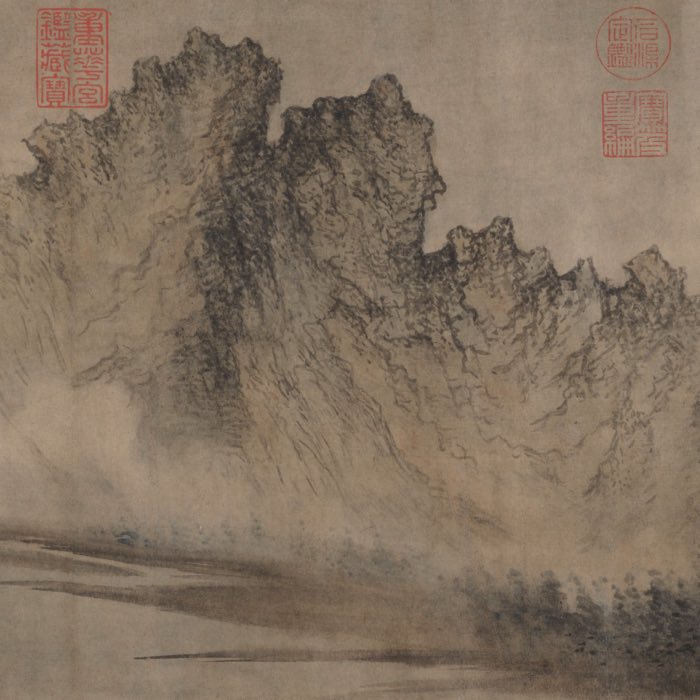

Modern reinterpretations of mindfulness often depict meditative postures in secular contexts. While inspired by Buddhist practices like sati, such representations frequently omit the ethical and soteriological dimensions that originally defined mindfulness as part of the Eightfold Path. Source: Jared Riceꜛ on Unsplashꜛ (license: Unsplash Licenseꜛ).

Modern reinterpretations of mindfulness often depict meditative postures in secular contexts. While inspired by Buddhist practices like sati, such representations frequently omit the ethical and soteriological dimensions that originally defined mindfulness as part of the Eightfold Path. Source: Jared Riceꜛ on Unsplashꜛ (license: Unsplash Licenseꜛ).

The meaning of sati in early Buddhism

In the earliest textual sources, sati is best understood as a faculty of memory and recollection. The term is rooted in the verbal form “to remember” (sarati), indicating that its original connotation is not simply awareness of the present moment, but the capacity to recall, bear in mind, and remain attentive to relevant aspects of experience, doctrine, or ethical commitments. Within the framework of the Pali Canon, particularly the Satipatthana Sutta, sati is presented as a foundational quality that supports the cultivation of insight (vipassana) and the development of the Eightfold Path.

Rather than being an isolated technique, sati functions as an integral component of a larger ethical and soteriological project. It enables a sustained attentiveness to bodily processes, sensations, mental states, and phenomena, but always in conjunction with a framework of disciplined observation and critical analysis. This use of mindfulness is not passive; it is a purposeful act of remembering the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama and applying them moment to moment.

Sati in the context of the Eightfold Path

Sati is one of the eight integral components of the Noble Eightfold Path, where it appears as samma-sati, or “right mindfulness.” This placement situates sati within a normative framework: it is not mindfulness in any generic sense, but mindfulness that is directed and shaped by ethical and epistemological concerns. Samma-sati involves remembering and applying the Four Noble Truths, recognizing impermanence (anicca), non-self (anatta), and suffering (dukkha), and using this awareness to undermine clinging and delusion.

In this context, sati becomes both a method and a means of liberation. It serves as a support for meditative concentration (samadhi), and through repeated contemplation of the changing and conditioned nature of experience, it lays the foundation for liberating insight. Importantly, sati is never a neutral awareness; it is a morally informed and conceptually structured attentiveness, always embedded in a broader system of Buddhist soteriology.

This Buddhist view of mindfulness presupposes what modern philosophy might describe as a process ontology — the understanding that reality is not composed of static entities but of interdependent and impermanent events. Sati is the mental faculty that tracks these events as they arise and pass, grounding awareness not in things, but in unfolding conditions. In this sense, mindfulness is not merely present-moment attention, but a disciplined way of seeing the dynamic nature of all phenomena. It fosters a shift from substance-thinking to process-seeing — an insight that is essential to the Buddhist path of transformation.

Later developments and interpretations

As Buddhism evolved across different regions and schools — such as in Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana traditions — the concept of sati retained its centrality while also undergoing significant reinterpretation. In the Abhidhamma literature, sati is classified as one of the mental factors (cetasikas) that arise in wholesome states of consciousness. It is described not only as awareness but as non-forgetfulness and non-distraction — qualities essential for ethical and spiritual progress.

In Mahayana texts, although the term sati may appear less frequently, the underlying principle persists under different designations, such as smṛti in Sanskrit. Here, mindfulness is often associated with bodhicitta (the aspiration toward enlightenment for the sake of all beings) and the practice of upaya (skillful means), extending its ethical implications to compassionate engagement with the world.

Sati and contemporary mindfulness movements

Modern mindfulness practices, particularly those popularized by figures such as Jon Kabat-Zinn, often draw upon Buddhist techniques while stripping them of their religious and doctrinal components. This process of secularization has led to a significant shift in how mindfulness is understood and applied. Rather than being embedded in a comprehensive path of liberation, contemporary mindfulness is often employed for pragmatic outcomes: reduced anxiety, improved focus, or enhanced productivity.

This transformation raises important questions about the integrity and implications of such adaptations. When sati is removed from its ethical and philosophical context, it risks becoming a commodified form of self-regulation — detached from the deeper insights into suffering, impermanence, and interdependence that formed its original core. Moreover, in its original context as one of the eight interlinked components of the Noble Eightfold Path, sati does not function independently but in constant interaction with other path factors such as samma-ditthi (right view), samma-vayama (right effort), and samma-samadhi (right concentration). This holistic structure ensures that mindfulness is always oriented by wisdom, sustained by ethical intention, and directed toward meditative clarity. Removing sati from this framework not only dilutes its transformative potential but also risks misrepresenting its role within the comprehensive Buddhist path to liberation.

Sati and Samadhi: Distinction and complementarity

While often practiced together, sati (mindfulness) and samadhi (concentration or meditative absorption) refer to distinct yet complementary faculties within the Buddhist path. Sati entails a vigilant attentiveness to the flow of experience, aimed at discerning patterns of impermanence, suffering, and non-self. It maintains a broad, inclusive awareness, sensitive to the arising and passing of mental and physical phenomena without clinging or aversion.

Samadhi, by contrast, involves the narrowing and stabilization of attention. It refers to a unified, focused mental state where distractions are subdued, and the mind becomes absorbed in a single object. This focused state allows for a deep inner stillness that supports the development of insight (vipassana), but it is not synonymous with mindfulness itself.

In the context of the Eightfold Path, samma-sati (right mindfulness) and samma-samadhi (right concentration) are placed in succession, underscoring their interdependence. Sati monitors the quality of attention and ensures that it remains grounded in ethical clarity and experiential awareness, while samadhi deepens that attention into sustained meditative absorption. Without mindfulness, concentration risks becoming rigid or escapist; without concentration, mindfulness may remain superficial and scattered. Together, they create the cognitive and emotional stability necessary for the cultivation of liberating insight.

Conclusion

The Buddhist concept of sati, or mindfulness, emerges as a complex and deeply embedded component of a broader spiritual and philosophical system. Rooted in recollection and ethical attentiveness, sati functions not merely as a technique but as a mode of being that facilitates insight, moral clarity, and ultimately liberation. Its development across different Buddhist traditions reflects both its central importance and its adaptability.

In its canonical formulation as samma-sati, or right mindfulness, sati is one of the eight integral and interdependent components of the Noble Eightfold Path. It works in concert with right view, right effort, and right concentration, among others, forming a cohesive and ethically grounded structure for spiritual development. This interconnectedness means that mindfulness in Buddhism is never an isolated practice; it is always contextually guided and informed by wisdom and ethical commitment.

Modern appropriations of mindfulness have undoubtedly brought some of its benefits to a wider audience, but they often do so at the cost of its depth and critical function. Stripped of its soteriological context, sati risks becoming a tool for coping with, rather than understanding and transforming, the conditions that produce suffering. While useful in managing stress and enhancing focus, secular mindfulness practices frequently neglect the broader existential and ethical insights that are central to the Buddhist approach.

The Buddhist framework offers not only methods for mental training but also a profound critique of selfhood, desire, and delusion — elements largely absent in mainstream Western mindfulness discourse. Recontextualizing sati within its original doctrinal structure reveals its potential as a holistic and transformative discipline aimed not merely at wellbeing, but at liberation from suffering itself.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments