The eight vijnanas: The Buddhist psychoanalysis

Among the many philosophical and psychological systems developed within Buddhism, the Yogācāra school of Mahayana Buddhism introduces one of the most elaborate models of consciousness. Central to this model is the concept of vijñāna (Pāli: viññāṇa), often translated as “consciousness” or “cognitive awareness”. Etymologically, the prefix vi- implies separation or discrimination, suggesting a divided or dualistic knowing that stands in contrast to the undivided awareness of enlightenment.

Illustration from a 19th-century Yoga manuscript (1899), showing the subtle body and Sapta Chakra system. Just as Tibetan traditional medicine and Tantric traditions examined the energetic and symbolic structure of the human body, the Yogācāra school developed a detailed inner cartography of the mind. The eightfold model of vijñāna offered a systematic framework for diagnosing cognitive and karmic processes, aiming not at physical healing, but at liberating insight and the cessation of suffering. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Illustration from a 19th-century Yoga manuscript (1899), showing the subtle body and Sapta Chakra system. Just as Tibetan traditional medicine and Tantric traditions examined the energetic and symbolic structure of the human body, the Yogācāra school developed a detailed inner cartography of the mind. The eightfold model of vijñāna offered a systematic framework for diagnosing cognitive and karmic processes, aiming not at physical healing, but at liberating insight and the cessation of suffering. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Yogācāra framework identifies eight distinct forms of consciousness, each contributing to how beings perceive, interpret, and act within the world. This model serves both as a metaphysical explanation of the cognitive process and as a diagnostic system for identifying the roots of delusion (moha) and suffering (dukkha). These eight vijñānas can be seen as the Buddhist counterpart to psychoanalysis, delineating layers of the mind and mechanisms of identity-formation, attachment, and transformation.

The eightfold network of consciousnesses

Emerging within the Yogācāra school of Mahayana Buddhism — founded by Asaṅga and Vasubandhu in the 4th–5th centuries CE — the theory of the eight vijñānas (aṣṭa vijñānakāyāḥ) reflects a sophisticated philosophical psychology that builds on earlier Abhidharma models (systematic scholastic elaborations of the Buddha’s teachings that aimed to analyze and categorize all phenomena, particularly mental and perceptual events, developed within the early Buddhist schools such as the Sarvāstivāda and Theravāda). Yogācāra, which literally means “practice of yoga,” was less concerned with metaphysical speculation than with analyzing the nature of cognition and delusion in the path toward liberation. The school’s emphasis on citta-mātra (“mind-only”) or vijñapti-mātra (“representation-only”) underscores its central claim: all experience is mediated by consciousness.

In this context, the eight vijñānas form a hierarchical and interactive system of mental functioning. These are:

- Cakṣu-vijñāna (eye-consciousness)

- Śrotra-vijñāna (ear-consciousness)

- Ghrāṇa-vijñāna (nose-consciousness)

- Jihvā-vijñāna (tongue-consciousness)

- Kāya-vijñāna (body-consciousness)

- Mano-vijñāna (mental consciousness)

- Kliṣṭa-mano-vijñāna or manas-vijñāna (defiled or self-reflective mind)

- Ālaya-vijñāna (storehouse consciousness)

The first six consciousnesses, collectively known as pravṛtti-vijñānāni (functional consciousnesses), are based on direct cognition (pratyakṣa), arising through contact between sense bases (āyatanas, i.e., eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind) and their respective objects (forms, sounds, smells, tastes, tactile sensations, and mental objects). These six include the five sense consciousnesses and the integrative mental consciousness (mano-vijñāna). They are considered “beautiful” or aesthetically direct in the sense that they relate immediately to the world.

The seventh consciousness, manas-vijñāna, is based on inferential cognition (anumāna). It reflects upon the ongoing activity of the first six and erroneously appropriates the stream of consciousness as a fixed self.

The eighth and most foundational consciousness, ālaya-vijñāna, is connected with reasoning cognition (yukti). It serves as the unconscious base in which karmic seeds (bīja) are stored and from which all other consciousnesses emerge.

These layers of consciousness function in concert, producing what is perceived as a coherent self and world. Yet according to Yogācāra thought, this apparent coherence is ultimately illusory, constructed through karmically conditioned processes and habitual identification with impermanent phenomena.

The first five consciousnesses: Sensory engagement with the world

The first five vijñānas correspond to the five traditional sense faculties: sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. Each sense-consciousness arises in dependence upon a specific sense organ (indriya) and its corresponding object (viṣaya). For instance, the cakṣu-vijñāna (eye-consciousness) arises when the eye contacts a visible form (rūpa); śrotra-vijñāna (ear-consciousness) arises from contact between the ear and a sound (śabda); ghrāṇa-vijñāna (nose-consciousness) with smells (gandha); jihvā-vijñāna (tongue-consciousness) with tastes (rasa); and kāya-vijñāna (body-consciousness) with tangible objects or tactile sensations (spraṣṭavya).

These five sensory consciousnesses are directly linked to the six internal-external bases of perception, known as āyatanas — the six internal sense bases (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind) and their six corresponding external objects (forms, sounds, smells, tastes, tactile sensations, and mental objects). Their arising is considered immediate and momentary, conditioned by contact (sparśa) between a sense base and its object.

Despite their immediacy, these consciousnesses are not integrated in themselves. They operate independently, and the data they provide remains raw and unprocessed. They do not produce conceptual understanding or judgments. The synthesis and interpretation of this sensory data is the domain of the sixth consciousness.

The sixth consciousness: manovijñāna

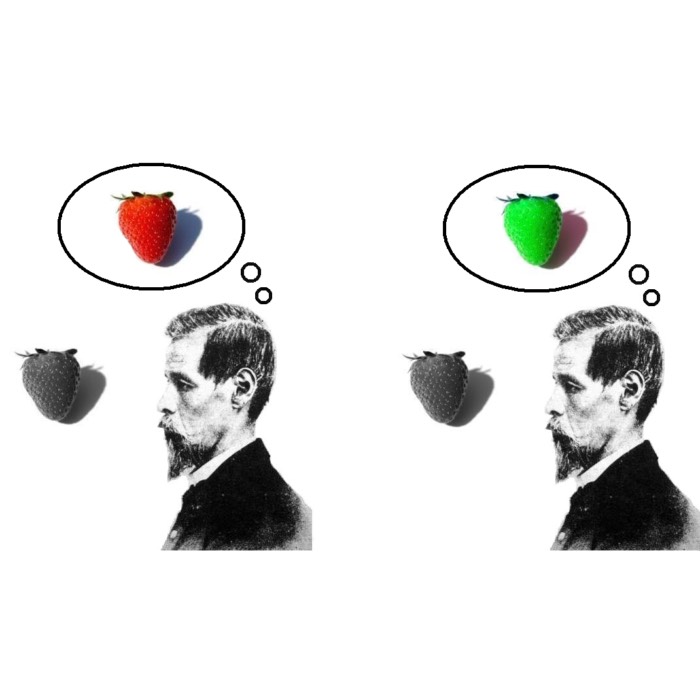

The manovijñāna, or mental consciousness, is the cognitive processor that integrates the data of the five senses. It allows for conceptualization, judgment, and volition. It is here that meaning is assigned to sensory input and where mental objects — thoughts, memories, anticipations — are also apprehended.

This sixth consciousness also serves as the basis for ethical valuation, decision-making, and narrative construction. It is the domain in which karmic intentions (Sanskrit: cetana) become operative, linking perception to action. However, it remains conditioned and transient. While capable of self-reflection, it is easily influenced by the deeper structures of delusion embedded in the seventh and eighth consciousnesses.

The seventh consciousness: kliṣṭamanovijñāna (or manas-vijñāna)

More subtle and insidious than the sixth consciousness is the manas-vijñāna, sometimes called the deluded or afflicted mind. This consciousness continually reflects upon the ālaya-vijñāna as “self.” It is responsible for the sense of ego, the abiding feeling that there is a subject behind experience.

While the sixth consciousness can operate without a sense of self — such as in moments of direct, unmediated perception — the seventh consciousness introduces a persistent cognitive distortion. It appropriates the contents of experience as belonging to a “me” or “mine,” generating clinging, aversion, pride, and other afflictions (kleśas).

In Yogācāra thought, the manas-vijñāna is not evil per se, but it is profoundly misled. Its delusion is not volitional but structural: it cannot help but construct the illusion of selfhood from the impersonal data of consciousness.

The eighth consciousness: ālayavijñāna, the storehouse

At the foundation of all experience lies the ālaya-vijñāna, or storehouse consciousness. It is said to retain the “karmic imprints” (vāsanāḥ) of all past experiences, thoughts, and actions in the form of latent seeds (bījas). These seeds mature when conditions ripen, giving rise to future experiences, including sensory perceptions, emotions, and volitions.

The ālaya-vijñāna is also referred to as the “basic consciousness” (mūla-vijñāna) or “causal consciousness”. According to the traditional interpretation, the other seven consciousnesses are “developing” or “changing” consciousnesses (pravṛtti-vijñānāni) that have their origin in this foundational consciousness. It accumulates all potential energy as seeds (bīja) that form the basis for the mental (nāma) and physical (rūpa) manifestation of one’s existence (nāma-rūpa or pudgala). In this way, the ālaya-vijñāna becomes the engine of continuous rebirth — the personality’s reformation in the wheel of samsāra.

From a broader perspective, the ālaya-vijñāna integrates into the process-like structure of the Five Skandhas by acting as the karmic substratum that conditions their moment-to-moment arising. Though not listed as an aggregate itself, it underlies and dynamically feeds into all five — from rūpa (form) to viññāṇa (consciousness). As such, it provides a unifying continuity across the otherwise discrete and impermanent skandhas, while remaining itself impermanent and conditioned. Rather than serving as a static essence, it is woven into the unfolding of the aggregates, thereby preserving the Buddhist rejection of an enduring self while still accounting for psychophysical continuity.

It is thus the source of our delusions, as it contains all the mental reaction and habit patterns that have formed in our experiential world. These are activated by the experiences of a particular moment. There are two possible ways this activation can unfold:

- When new experiences combine with stored memories and reaction patterns, the mind uses these to build its subjective reality. In doing so, the karmic patterns become more deeply anchored in the ālaya, perpetuating samsāra.

- However, if the arising patterns are recognized as mere constructions of mind — without inherent reality or selfhood — they lose their compelling force. No longer appropriated or clung to, these seeds cannot re-anchor themselves in the storehouse, thus weakening the cycle of rebirth and suffering.

The ālaya-vijñāna functions as a kind of deep memory structure, unconscious in nature, but dynamically involved in shaping the field of conscious awareness. It is neither good nor bad; it simply contains the traces of karmic conditioning accumulated over countless lifetimes.

While it is impersonal and pre-reflective, the ālaya-vijñāna is not permanent. It too is conditioned, subject to transformation (parāvṛtti) through insight and practice. In advanced stages of realization, it is said that the ālaya transforms into a non-dual awareness free of subject-object dichotomy, sometimes referred to as amalavijñāna (pure consciousness) in some sub-traditions.

Transforming consciousness: Toward prajñā and liberation

The function of the eightfold consciousness system is not merely descriptive but soteriological. It offers a means by which delusion can be understood and ultimately overcome. In Yogācāra thought, ignorance (avidyā) is not simply a failure to know but a misidentification of impermanent, conditioned phenomena as permanent and self-existing. The manas-vijñāna, in its habitual clinging to the ālaya-vijñāna as “self,” becomes the pivot around which samsāric suffering revolves.

By bringing to awareness the processes by which the various vijñānas function and interrelate, the practitioner — according to Yogācāra theory — can begin to dissolve their mistaken views of reality. Through meditative insight and analysis, the deluded projections of the mind can be recognized as empty (śūnya) of intrinsic selfhood. This recognition is the gateway to wisdom (prajñā).

The transformation (parāvṛtti) of the eighth consciousness is a particularly important goal in this process. When karmic imprints are no longer reinforced by clinging and identification, the ālaya-vijñāna ceases to generate the conditions for rebirth and suffering. In this way, the transformation of consciousness directly supports the cessation of dukkha and escape from saṃsāra.

Rather than relying on metaphysical beliefs or divine intervention, the Yogācāra system provides a model for self-transformation grounded in psychological and phenomenological analysis. It illustrates how liberation is possible through cognitive restructuring, achieved not by eliminating consciousness but by purifying and reorienting it toward non-dual awareness.

Reception

The influence of Yogācāra thought, especially its theory of consciousness, extended across various strands of East Asian Buddhism. In China, it became a cornerstone of the Fǎxiàng school, while in Japan, it informed the Hossō school. Even in Tibetan Buddhism, Yogācāra terminology and ideas were integrated into later Madhyamaka interpretations, particularly within the Dzogchen and Mahāmudrā traditions.

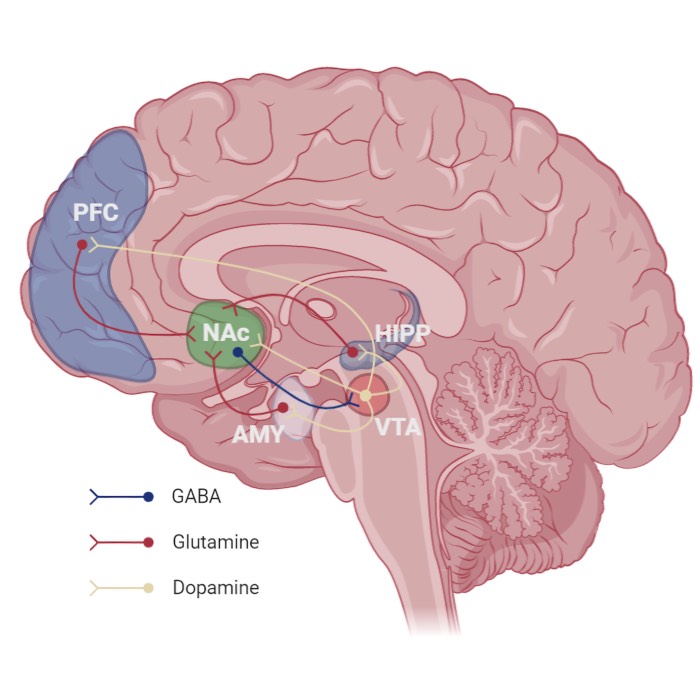

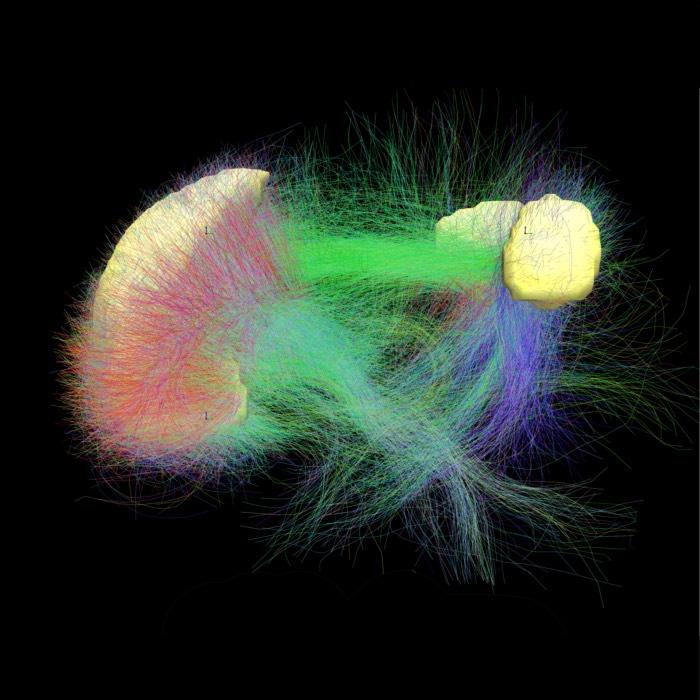

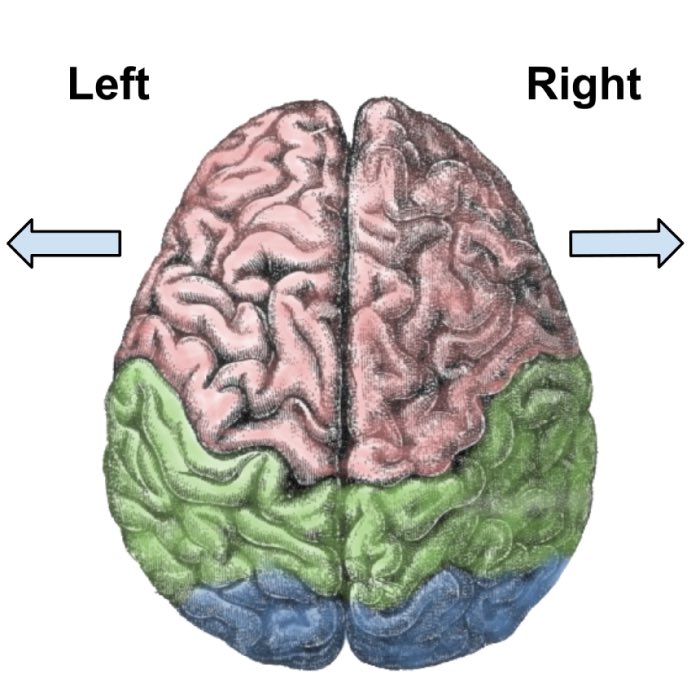

In the modern period, the Yogācāra school as a formal institution has largely faded, but its insights remain influential. Contemporary Buddhist scholarship, psychology, and even cognitive science have taken interest in its analytic depth, particularly the model of the ālaya-vijñāna as a precursor to concepts like the unconscious or implicit memory. Scholars such as Thomas Kochumuttom (1982) and William S. Waldron (2003) have noted similarities between Yogācāra models and contemporary cognitive psychology, especially in relation to mental schemas, habitual patterning, and the persistence of cognitive bias. Likewise, the structure of ālaya-vijñāna has been loosely compared to non-conscious processing, long-term memory, and predictive coding models in cognitive neuroscience (see Varela, Thompson & Rosch, The Embodied Mind, 1991; Damasio, Self Comes to Mind, 2010; Waldron, The Buddhist Unconscious, 2003). While not directly mapped onto modern frameworks, its sophisticated exploration of perception, cognition, and identity formation continues to provide valuable dialogue with contemporary thought.

Conclusion: Psychoanalysis without a self

The eight vijñānas present an elaborate and layered model of consciousness that functions both as a philosophical framework and a therapeutic tool. Long before the emergence of Western psychoanalysis in the 19th and 20th centuries, Yogācāra Buddhism had already articulated a detailed account of mental functioning, delusion, and behavioral conditioning. Its analysis of how experience and identity are constructed through multiple interacting layers of consciousness anticipates key insights from modern psychological theory — yet with a distinct metaphysical orientation grounded in non-self (anātman) and karmic causality.

Unlike Western psychoanalytic traditions, which tend to preserve the notion of a core self or ego — whether as a regulator (Freud), a chooser (existentialism), or a cognitive subject (Descartes) — Yogācāra radically denies such enduring selfhood. All eight consciousnesses are seen as transient, dependently arisen processes. The illusion of a unified ego emerges from misidentification with these processes, particularly through the workings of the manas-vijñāna and its fixation on the ālaya-vijñāna as “self.”

This system provided practitioners with both explanatory depth and a roadmap for liberation. By identifying the sources of perceptual distortion and habitual reactivity, practitioners could develop awareness (sati) and wisdom (prajñā) to break the cycles of dukkha and saṃsāra. The vijñānas thus served as a diagnostic schema for introspective observation and transformation, not only describing how delusion functions but enabling its dismantling.

In this light, the Yogācāra model represents a unique pre-modern form of psychoanalysis — comprehensive in scope, deeply ethical in orientation, and aimed at profound existential transformation. Whether approached historically, philosophically, or clinically, it remains one of the most systematic and nuanced contributions to the understanding of the human mind without resorting to the fiction of a permanent self.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Kochumuttom, Thomas. A Buddhist Doctrine of Experience: A New Translation and Interpretation of the Works of Vasubandhu the Yogācārin, 1989, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120806627

- Waldron, William S. The Buddhist Unconscious: The Ālaya-Vijñāna in the Context of Indian Buddhist Thought, 2006, RoutledgeCurzon, ISBN: 978-0415406079

- Varela, Francisco J.; Thompson, Evan; Rosch, Eleanor. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience, 2017, MIT Press, ISBN: 978-0262529365

- Damasio, Antonio. Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain, 2012, Vintage, ISBN: 978-0099498025

- Hayes, G.A.; Timalsina, S., “Introduction to “Cognitive Science and the Study of Yoga and Tantra””, 2017, Religions, 8, 181. DOI: 10.3390/rel8090181ꜛ

- Srinivasan, Narayanan, Consciousness Without Content: A Look at Evidence and Prospects, 2020, Frontiers in psychology vol. 11 1992, DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01992ꜛ

comments