Nāgārjuna and his role in the development of Buddhist philosophy

The Indian philosopher Nāgārjuna, active between the second and third centuries CE, is regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of Buddhist thought. He is widely recognized as the founder of the Madhyamaka school, or the “Middle Way” school of Mahayana Buddhism. His works, especially the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way), are considered profound philosophical contributions that have shaped the development of Buddhist theory and practice for centuries. This influence, however, is not to be understood as a deviation or radical departure from the original teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, but rather as a clarification and deepening of the core principles already present in early Buddhism. Nāgārjuna’s efforts can be viewed as a systematic defense of dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda), non-self (anattā), and the rejection of essentialism — concepts foundational to Siddhartha’s philosophy.

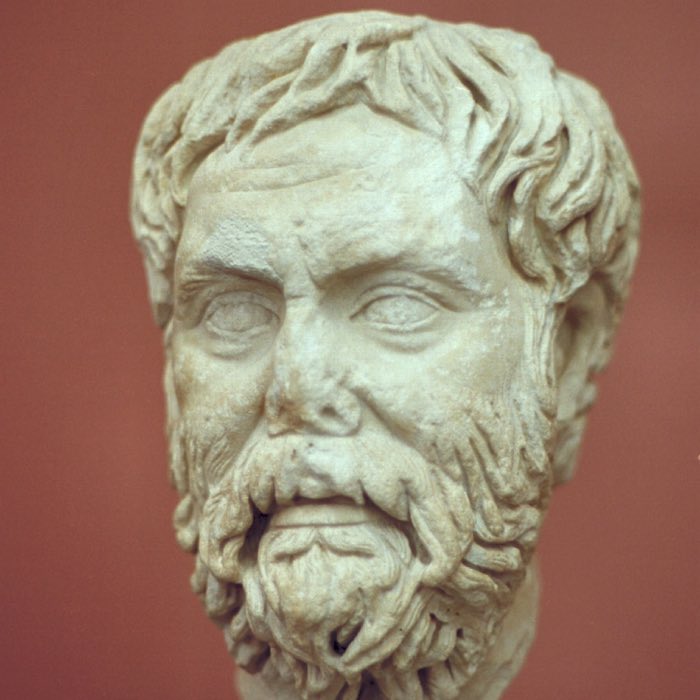

“Nāgārjuna Conqueror of the Serpent” by Nicholas Roerich, 1925. In a legendary tale, Nāgārjuna attracts the attention of a mythical race of dragon-like serpent beings, the Nāgas, through his discourses. Out of appreciation, they invite Nāgārjuna to their home world at the bottom of the sea and hand him the Prajñāpāramitā scriptures, which the Buddha himself is said to have given them for safekeeping, with the request that they only be made accessible to the world public when people were ready for their message. This legend alludes to the meaning of the name “Nāgārjuna”, which translates roughly as “white snake”. Indian mythology associates the color white (arjuna) with purity and the symbol of the snake (nāga) with wisdom. A distinguishing feature of Nāgārjuna is therefore the snakes that rise up behind his head in traditional depictions. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Biography and historical context of Nāgārjuna

Nāgārjuna is believed to have lived in southern India during the second to third century CE, though precise biographical details remain scarce and are often entwined with legend. He is traditionally associated with the region of Andhra Pradesh and sometimes linked to the Buddhist monastic university at Nālandā, though the latter is more a reflection of his intellectual legacy than a verified historical affiliation.

According to later biographical traditions, Nāgārjuna was born into a Brahmin family but became disillusioned with Vedic ritualism and turned toward the renunciant path, eventually becoming a Buddhist monk and scholar. Some accounts attribute to him alchemical or tantric interests, but these appear in later hagiographies and should be treated with caution when reconstructing his philosophical role. His most important contribution lies in his body of philosophical writings, particularly the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way), in which he systematically elaborates and defends the doctrine of emptiness.

Nāgārjuna’s works mark a pivotal point in the evolution of Buddhist philosophy, as they respond both to internal Buddhist developments and to external philosophical challenges, particularly from schools of Brahmanical thought. His method and tone suggest he was addressing contemporaneous philosophical debates while also clarifying the trajectory of Buddhist teaching. It is within this historical matrix that the Madhyamaka school emerged.

Historical context and the emergence of Madhyamaka

By the time Nāgārjuna composed his works, Buddhism had undergone significant evolution. Following the death of Siddhartha Gautama in the fifth century BCE, various schools emerged that sought to preserve and interpret his teachings. As Buddhist institutions expanded and Mahayana Buddhism gained prominence, new philosophical questions emerged — not only concerning the nature of enlightenment and nirvana, but also the validity of language, logic, and conceptual frameworks themselves. In this intellectual environment, Nāgārjuna formulated a rigorous critique of all views that sought to reify Buddhist concepts into absolute or self-existing truths.

The central concern that motivated Nāgārjuna’s philosophy was the creeping essentialism that had begun to influence Buddhist thought. Even concepts such as nirvana, karma, or the path to liberation risked being interpreted as possessing inherent, independent existence. Nāgārjuna recognized this as a misunderstanding that contradicted the early Buddhist emphasis on impermanence (anicca), conditionality, and process.

Emptiness as a refinement of dependent origination

At the heart of Nāgārjuna’s philosophy lies the concept of śūnyatā, or emptiness. Contrary to popular interpretations that view this term as denoting nihilism or nonexistence, Nāgārjuna defines emptiness as the absence of intrinsic essence (svabhāva) in all phenomena. This definition is not novel in a vacuum; it is a conceptual elaboration of Siddhartha’s teaching on dependent origination — the principle that all phenomena arise in dependence upon causes and conditions, and therefore lack an independent, unchanging core. This also directly reinforces the doctrine of non-self (anattā), which asserts that what we conventionally refer to as a “self” is likewise a process composed of conditioned and impermanent aggregates (five skandhas), devoid of any fixed or intrinsic identity.

For Nāgārjuna, to say that a thing exists in dependence upon other conditions is to say that it does not possess a fixed essence — in full accordance with the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama. Therefore, the true nature of all things is emptiness. But rather than declaring emptiness as some ultimate metaphysical reality, Nāgārjuna emphasizes that emptiness itself is empty — it is a conceptual tool, a linguistic and philosophical strategy to dismantle dogmatic views and fixed ideas. His goal is not to replace one dogma with another, but to demonstrate the limitations of all fixed positions.

This is especially evident in his oft-quoted verse from Mūlamadhyamakakārikā 24.18:

“We state that conditioned origination is emptiness. It is a dependent designation, and is itself the middle way.”

In these few lines, Nāgārjuna identifies dependent origination and emptiness as conceptually equivalent and affirms the validity of the conventional world — so long as it is not misunderstood as containing inherent essence.

Deconstruction without destruction

Nāgārjuna’s methodology is dialectical. Rather than proposing positive metaphysical claims, he employs a form of logical analysis that deconstructs the very foundation of such claims. This technique often involves demonstrating that all conceptual positions — whether affirming existence, non-existence, both, or neither — inevitably lead to contradiction when taken as ultimate truths. This fourfold negation (catuṣkoṭi) does not aim to reject the world, but to undercut the conceptual reification that leads to suffering and delusion. A typical example of such a fourfold negation would be a question like: “Does the Tathāgata exist after death?” To which the response would be:

- he exists,

- he does not exist,

- he both exists and does not exist,

- he neither exists nor does not exist.

All four propositions are then shown to be conceptually incoherent when taken as ultimate truths. The purpose is not to offer a new metaphysical position, but to expose the limits of conceptual thinking itself. Through this, the catuṣkoṭi aims to loosen the grip of fixed views and reveal that liberation cannot be reached through conceptual construction or philosophical speculation. Instead, by revealing the contradictions and dependencies within all views, the fourfold negation functions as a tool for dislodging cognitive attachment and paving the way for direct, non-conceptual insight — which is, ultimately, in harmony with the experiential awakening sought in Buddhist practice.

In this sense, Nāgārjuna’s work echoes and extends Siddhartha Gautama’s early teachings on the danger of clinging. What Siddhartha had described as the root of suffering — the attachment to sensory experiences, to the illusion of self, and to rigid views — Nāgārjuna targeted at the conceptual level. Through his rigorous method of analysis, he demonstrated how philosophical positions themselves could become subtle forms of clinging when mistaken for ultimate truths. By dissolving the seeming solidity of all views, Nāgārjuna aimed to create the cognitive conditions necessary for a direct and unmediated perception of reality, free from conceptual overlay. — not only to sensory pleasures or personal identity, but to views and ideas. Nāgārjuna’s emptiness is not an endpoint or a metaphysical principle; it is a mirror that reflects the insubstantiality of all things, including the doctrines of Buddhism themselves. This point has far-reaching implications: it suggests that the path to liberation involves not merely ethical behavior or meditative practice, but a fundamental shift in one’s cognitive relationship to concepts, identity, and reality itself.

Speculated links between Nāgārjuna and Pyrrhonism

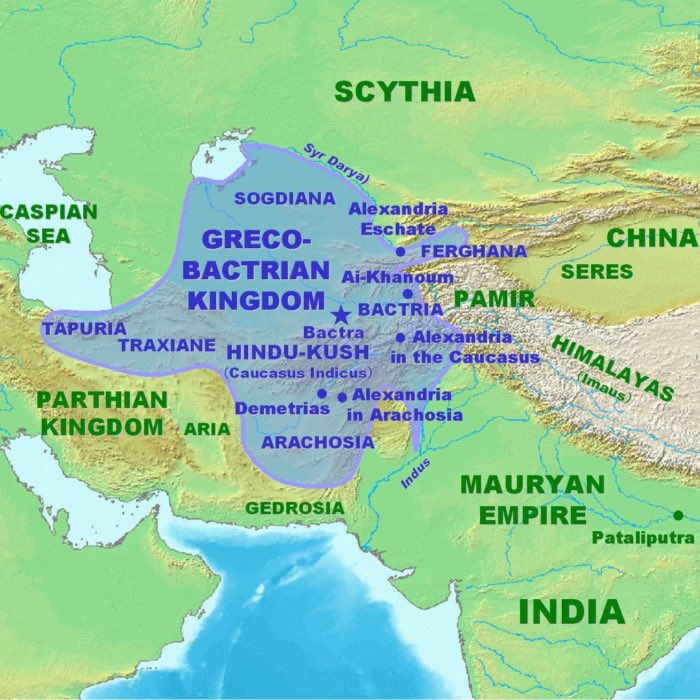

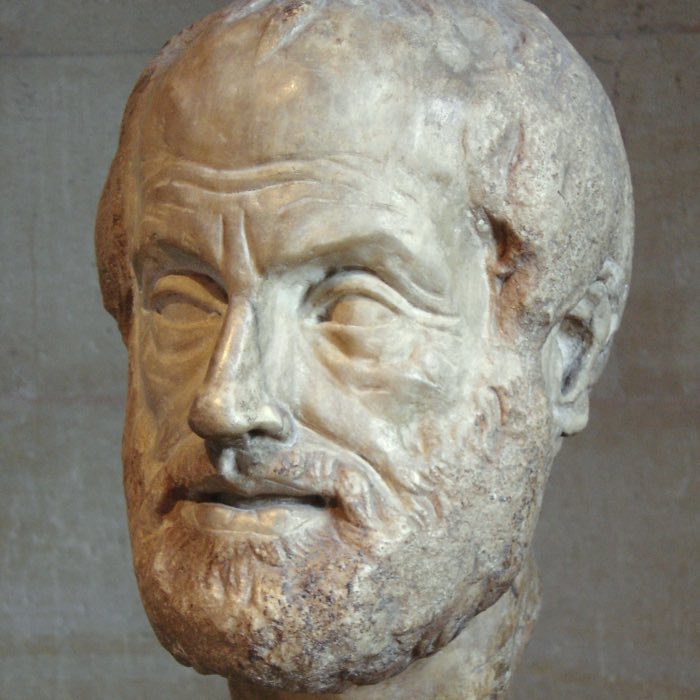

Some modern scholars have speculated about potential parallels or even historical connections between Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka philosophy and ancient Greek Pyrrhonism, particularly the works of Sextus Empiricus. Both traditions deploy a radical form of skepticism, not to deny reality outright, but to suspend judgment on all dogmatic claims and thereby attain a state of peace — ataraxia in the Pyrrhonist tradition, and nirvāṇa in the Buddhist. The methodological similarities include the rejection of fixed views, the use of dialectical reasoning to undermine assertions, and the aim of cognitive detachment from conceptual commitment.

While there is no concrete historical evidence proving direct influence, these similarities have led some to suggest that there may have been philosophical cross-pollination through the Hellenistic-Indian exchanges following the conquests of Alexander the Great and the Indo-Greek kingdoms that flourished in parts of northwest India during the early centuries BCE and CE. Others maintain that these resemblances are coincidental, arising independently in response to similar epistemological and existential concerns.

The comparison underscores the universality of the philosophical concerns addressed by both Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka and Pyrrhonism. Each tradition, in its own context, explores the limitations of thought and language in apprehending ultimate reality, reflecting a shared human pursuit that transcends cultural and geographical boundaries.

Continuity and influence

Nāgārjuna’s contribution to Buddhist philosophy is not a departure from Siddhartha Gautama’s core insights, but a continuation that aims to secure them against misinterpretation. Siddhartha had described how suffering arises through clinging — not only to pleasures or identity, but to ideas, views, and frameworks that give the illusion of stable ground. Nāgārjuna takes this observation seriously and extends it into the realm of philosophical thought itself.

His method does not introduce new doctrines in the sense of novel metaphysical assertions. In my opinion, while the term śūnyatā (emptiness) might appear as a new conceptual element, it is not intended as an additional ontological claim, but as a clarification of already existing principles — most notably, dependent origination and non-self. Nāgārjuna does not assert emptiness as a new substance or reality, but employs it as a tool to expose the lack of intrinsic essence in all things, thereby reaffirming and protecting the original insights of Siddhartha Gautama. Instead, it dismantles the tendency to treat even Buddhist teachings as ultimate truths with fixed content. By systematically revealing the contradictions in all conceptual standpoints, including notions like existence, non-existence, and nirvana, Nāgārjuna prevents the solidification of ideas into dogma. His approach serves as a philosophical safeguard, reminding interpreters that liberation lies not in affirming new truths, but in freeing the mind from the habit of clinging to any view at all.

Rather than presenting the Middle Way as a compromise between opposing metaphysical positions, Nāgārjuna uses it to expose the assumptions behind those oppositions. In doing so, he offers a more precise expression of early Buddhist thought — not by adding something new, but by clarifying what was already implicit in Siddhartha’s emphasis on conditionality, impermanence, and non-self. This conceptual clarity would become foundational for later Mahayana developments, which sought to express the path not as a system of doctrines, but as a transformative insight into the very structure of experience.

Conclusion

Nāgārjuna’s contribution to the development of Buddhist philosophy lies not in introducing new metaphysical content, but in protecting the early teachings of Siddhartha Gautama from misinterpretation and conceptual reification. By rigorously clarifying the logic behind dependent origination and non-self, Nāgārjuna articulates the doctrine of emptiness (śūnyatā) not as a nihilistic denial of existence, but as a methodological tool to dismantle the illusion of essence — in all things, including Buddhist teachings themselves.

His use of the catuṣkoṭi and the radical deconstruction of all four possible truth positions — affirmation, negation, both, and neither — demonstrates a philosophy that resists all attempts to pin down reality in fixed categories. This makes Nāgārjuna’s approach one of the most refined examples of process-based thinking in the history of philosophy. Unlike systems that propose a stable ontology or a final metaphysical truth, his method guides into a space where all claims are provisional, contingent, and ultimately empty.

Critically, this distinguishes Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka from many strands of Western philosophy, which often pursue a foundational ground: whether substance (as in Aristotelian metaphysics), the thinking subject (as in Descartes), or transcendental conditions (as in Kant). Even Western skepticism, as found in Pyrrhonism, does not go as far as Nāgārjuna in applying doubt to the very structures of logical inference and linguistic formulation. Where Western thought frequently seeks to arrive at certainty — even if only by delimiting what can be known — Nāgārjuna’s project is to show that clinging to the project of certainty itself is a form of suffering. He does not propose a new theory to believe in, but invites a cognitive and existential unbinding from all such commitments.

In this context, Buddhism — at least in this specific philosophical formulation — appears uniquely consistent in its refusal to turn insight into dogma. Emptiness, in Nāgārjuna’s hands, becomes a mirror to thought itself: a way to see how even liberating ideas can become limiting when misunderstood as absolute. Liberation, then, is not achieved through the accumulation of correct views, but through the dissolution of the very need for fixed views.

In this way, Nāgārjuna’s work can be understood as a systematic effort to clarify and preserve the implications of Siddhartha Gautama’s core insights. Rather than proposing a new metaphysical framework, he highlights the risks involved in treating philosophical ideas — including Buddhist ones — as final or absolute. His approach reinforces the early Buddhist view that clinging, whether to material objects, personal identity, or conceptual frameworks, leads to distortion and suffering. By subjecting all views to critical analysis, Nāgārjuna’s philosophy offers a consistent method for resisting reification and maintaining the provisional character of all conceptual tools within the path to liberation.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Bernhard Weber-Brosamer, Dieter M Back, Die Philosophie der LLeere: Nāgarjunas Mula-Madhyamaka-Karikas, 2006, Harrassowitz, O, ISBN-10: 9783447052504

- Lutz Geldsetzer, Nagarjuna, Die Lehre von der Mitte - (Mula-madhyamaka-karika) Zhong Lu, 2010, Meiner, F, ISBN: 9783787321377

- Nāgārjuna, David J. Kalupahana, Mūlamadhyamakakārikā of Nāgārjuna, 1991, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN: 9788120807747

- Christopher I. Beckwith, Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia, 2015, Princeton University Press, ISBN 10: 0691166447

comments