The Six Patriarchs of Zen: Foundations and transformations of the Chán tradition

Zen (Chán) places special emphasis on direct realization, meditative practice, and the transmission of insight from teacher to student. Central to this lineage-based model of spiritual authority is the narrative of the “Six Patriarchs” — a succession of figures who, according to tradition, preserved and conveyed the essence of Zen through a direct, mind-to-mind transmission. Far more than mere historical personalities, these patriarchs came to symbolize key developments in the evolution of Zen thought and practice from its roots in India to its distinct formation in China. In this post, we briefly explore the lives and teachings of these six pivotal figures, tracing their impact on the development of Zen and its subsequent diversification into various schools.

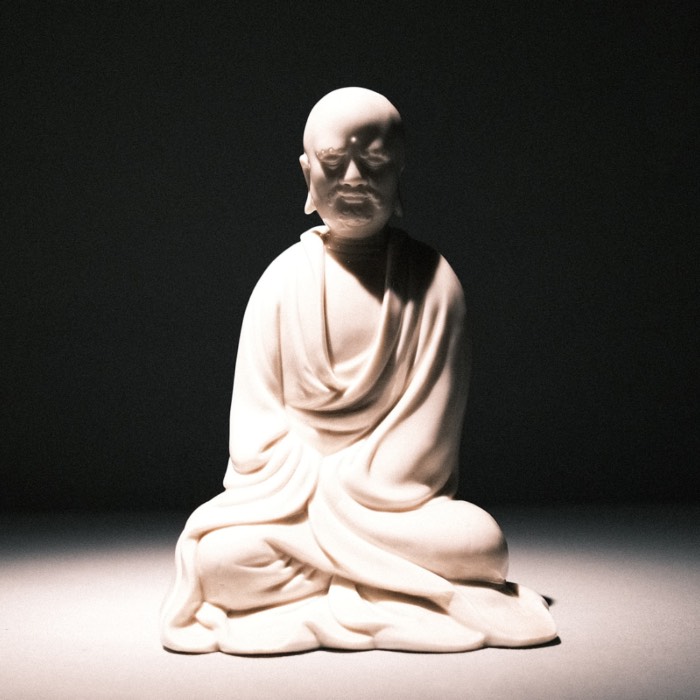

Life-size sculpture of the seated Bodhidharma, Ming dynasty, North China, stoneware with green and brown glaze, 1484. Bodhidharma and five other (Chinese) patriarchs are traditionally considered the founders of Chán (Zen) Buddhism. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

The role of the patriarchs in Zen Buddhism

The notion of unbroken transmission lies at the heart of Zen’s identity. Unlike scholastic schools that root authority in scriptural commentary, Zen emphasizes personal realization — awakening to the nature of mind as it is. According to tradition, this began with a non-verbal transmission from Siddhartha Gautama (the historical ](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-05-18-siddhartha_gautama/)) to his disciple Mahākāśyapa, symbolized by the well-known story of the udumbara flower: the Buddha silently held up a flower before his assembly, and only Mahākāśyapa smiled, signifying a shared understanding beyond words.

From this moment, Zen traces a direct lineage through twenty-seven Indian patriarchs, culminating in the twenty-eighth, Bodhidharma. As discussed in the previous article, Bodhidharma traveled to China in the early 6th century and catalyzed a shift away from textual reliance and toward direct meditative realization. He is therefore regarded as the First Patriarch of Chinese Zen. The transmission continued through five more patriarchs, each of whom played a formative role in shaping the early identity of Chán Buddhism.

The Six Patriarchs are:

- Bodhidharma 菩提達磨 (Japanese: Bodaidaruma or short: Daruma) (~440-~528 CE)

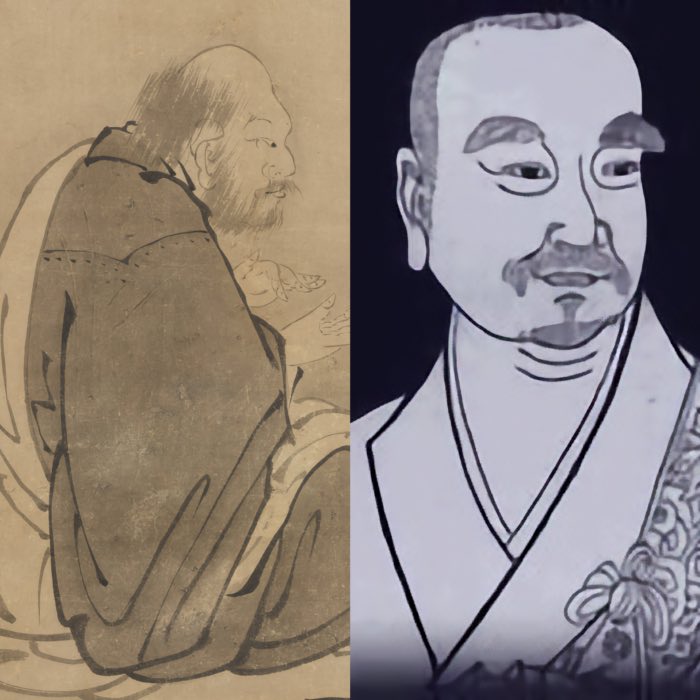

- Dazu Huike 大祖慧可 (Japanese: Taiso Eka) (487–593)

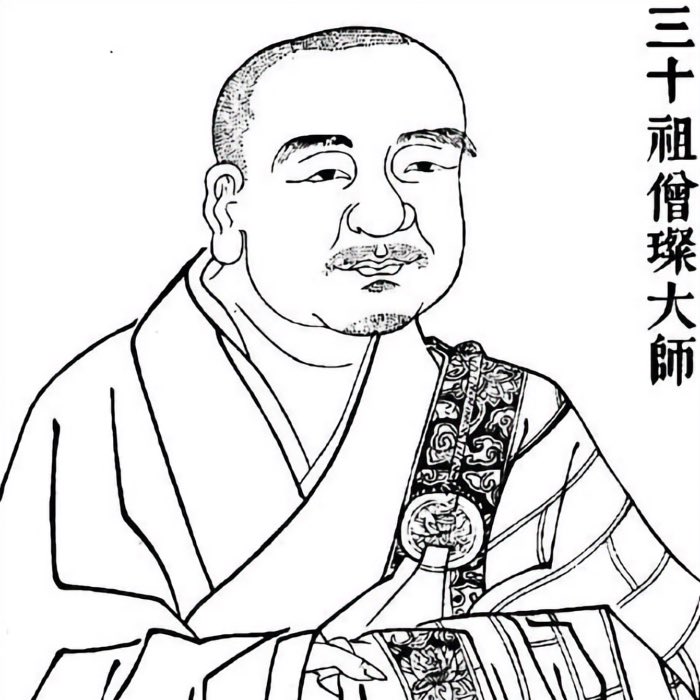

- Jianzhi Sengcan 僧璨 (Japanese: Kanchi Sōsan) (d. 606)

- Dayi Daoxin 道信 (Japanese: Dai’i Dōshin) (580–651)

- Daman Hongren 弘忍 (Japanese: Daiman Kōnin) (601–674)

- Dajian Huineng 大鑒惠能; (Japanese: Daikan Enō) (638–713)

The Six Patriarchs of Zen

The Six Patriarchs of Zen are not merely historical figures; they represent a lineage of awakening that transcends time and space. Each patriarch embodies a unique aspect of Zen practice and philosophy, contributing to the rich tapestry of Chán thought. Below, we briefly explore the lives and teachings of these six pivotal figures. In subsequent posts, we will explorer each of them in greater detail, focusing on their teachings and the impact they had on the development of Zen.

1. Bodhidharma: The first patriarch in China

Bodhidharma is credited with bringing the Zen teaching to China and is known for emphasizing meditation (dhyāna), the rejection of merit-based religiosity, and a “special transmission outside the scriptures”. His teachings laid the philosophical and practical foundations for the Chán tradition, though historical details about his life remain sparse and partially legendary. We have explored Bodhidharma’s historical and symbolic significance in detail in the previous article; you’ll find more on his life, teachings, and legacy in our previous article if you’re curious to dive deeper.

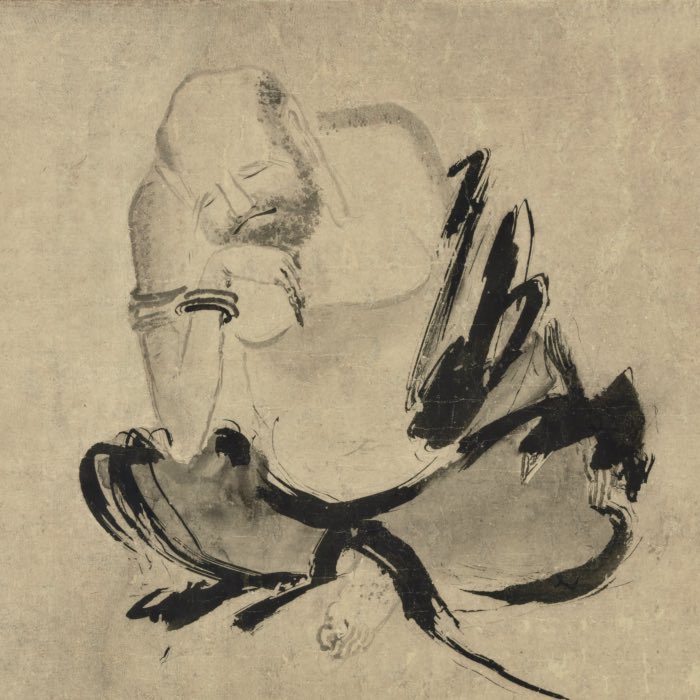

2. Huike: Transmission through action

Huike, Bodhidharma’s foremost disciple, is most famously known for cutting off his own arm to demonstrate his sincerity in seeking the Dharma. He emphasized meditative insight over scholasticism and is remembered for continuing the transmission in a manner deeply aligned with Zen’s emphasis on experiential transformation. Huike’s own teachings remain obscure, but his legacy lies in the intensity and immediacy with which he approached practice.

3. Sengcan: Harmony with emptiness

Sengcan, the third patriarch, is traditionally regarded as the author of the famous Zen poem Xinxin Ming (Faith in Mind), although historical attribution is uncertain. His teaching style emphasized non-duality, equanimity, and a calm acceptance of the mind’s movements. He is considered to have helped stabilize the early tradition and integrate Chinese philosophical elements into Chán.

4. Daoxin: Founding the monastic framework

Daoxin marked a turning point in the institutional development of Chán. Under his leadership, Zen began to establish a more formal monastic presence, particularly at Mount Lu. He emphasized seated meditation (zuochan) as central to the path and linked meditative discipline with everyday conduct. His teachings were more systematic and began to lay the groundwork for the later codification of Zen methods.

5. Hongren: Refinement and expansion

Hongren, Daoxin’s successor, is often seen as the real organizer of early Chán. He presided over a large monastic community at Mount Dongshan and developed a structured approach to meditation and ethical discipline. Hongren’s teaching emphasized the “pure mind” and introspective clarity, laying the groundwork for both gradual and sudden models of enlightenment. He was instrumental in broadening the social base of Zen, attracting lay and monastic students alike.

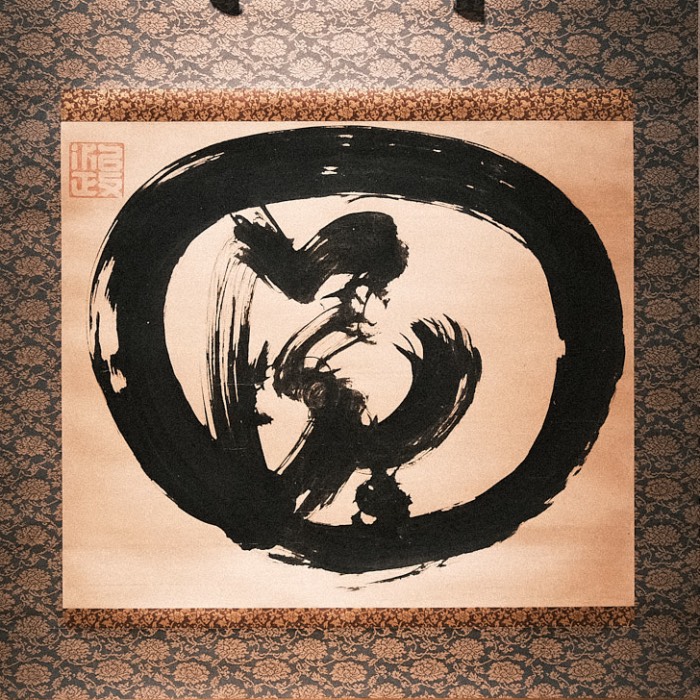

6. Huineng: The iconoclast and the Southern School

Huineng (638–713), the Sixth and final official Patriarch, is perhaps the most celebrated and transformative figure in the Chán tradition. Coming from humble, illiterate beginnings, Huineng’s sudden enlightenment upon hearing the Diamond Sūtra became emblematic of the idea that awakening is not dependent on scriptural knowledge or social status. The Platform Sūtra of the Sixth Patriarch, attributed to him, became one of the core texts of Chán.

Huineng (638–713) advocated for a sudden, non-gradual realization of one’s original mind and taught that practice and awakening are not sequential but simultaneous. His succession sparked a famous division between the so-called “Northern School” (gradual enlightenment) and the “Southern School” (sudden enlightenment), though later scholars suggest this split was rhetorically amplified by his disciples.

Beyond the sixth patriarch: Differentiation and growth

After Huineng (638–713), the Chán tradition diversified into multiple lineages and schools, moving away from a single patriarchal succession. While earlier patriarchs served to legitimize Zen’s continuity from the Buddha, later generations began emphasizing stylistic and methodological variations. The most significant outcome was the emergence of the Five Houses of Zen (Chán), each associated with distinct styles of teaching:

- Guiyang Zong (named after Guishan and Yangshan; also read Weiyang School): Founded in the 9th century, this school is known for its poetic, metaphorical style and subtle approach to awakening. It emphasized harmony between master and student and often used illustrative dialogues.

- Linji Zong (Rinzai-shū in Japanese): Originating in the 9th century and still active today, Linji is known for its vigorous methods, including shouting (katsu) and striking, to jolt students into realization. It stresses sudden enlightenment and strong personal presence in the teacher-student relationship.

- Caodong Zong (Sōtō-shū in Japanese): Founded in the 9th century, Caodong emphasizes silent illumination (mozhao) — a form of non-dual meditation that combines concentration and insight. Brought to Japan as the Sōtō school, it remains one of the two main Zen traditions in Japan.

- Fayan Zong: Also emerging in the 9th century, the Fayan School is noted for its refined doctrinal synthesis and use of sophisticated discourse. It often highlighted interpenetration and mutual dependence in understanding reality.

- Yunmen Zong: Named after Master Yunmen Wenyan (862–949), this school is known for its concise, cryptic one-word answers or short phrases used to awaken students. It emphasized the immediacy of awakening and often displayed a sharp, paradoxical teaching style.

These schools maintained shared emphasis on direct insight and teacher-student transmission but differed in tone, method, and institutional structure. The concept of a “patriarch” gradually gave way to more decentralized models of authority, where awakened masters transmitted the Dharma based on realization rather than formal inheritance.

Conclusion

The story of the Six Patriarchs of Zen provides more than a historical lineage — it reveals how Chán Buddhism developed both structurally and philosophically from its Indian roots into a distinct Chinese tradition. From Bodhidharma’s radical emphasis on direct experience and rejection of ritual, to Huineng (638–713)’s iconic articulation of sudden enlightenment and the accessibility of awakening to all, the patriarchs served not only as spiritual authorities but also as narrative anchors for the evolving identity of Zen.

Across the biographies of these six figures, certain themes recur: a persistent critique of institutional formalism, a call to return to meditative simplicity, and a conviction that awakening cannot be transmitted through texts alone. While the historical accuracy of some elements remains debated, the functional role of the patriarchs — as models of practice and touchstones of legitimacy — remains clear. Each patriarch marks a stage in the movement of Zen from esoteric marginality to monastic prominence.

Yet we also highlighted a critical shift: after Huineng (638–713), authority in Zen becomes less centralized. The proliferation of schools such as Linji, Caodong, and Yunmen reflects a transition away from patriarchal succession toward more diversified expressions of the Dharma. This flexibility allowed Zen to remain vital and responsive to different cultural and spiritual needs across East Asia.

In critically assessing the role of the patriarchs, it becomes clear that Zen’s lineage is less about fixed doctrine and more about the continuity of an attitude — an attitude grounded in questioning, directness, and practice. The patriarchs, whether historically precise or symbolically embellished, embody the core of what Zen seeks to preserve: a living transmission that bypasses conceptual filters to touch the root of human experience.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

comments