Dajian Huineng: The sixth patriarch and the great divergence in Chinese Zen

Dajian Huineng (大鑒惠能; Japanese: Daikan Enō) is widely regarded as the Sixth Patriarch of Chinese Zen (Chán) and one of its most transformative figures. While his historical biography is shrouded in uncertainty and myth, the ideas and texts associated with his name — especially the Platform Sūtra — profoundly shaped the trajectory of Zen thought and practice. Huineng’s legacy marks a watershed in the development of Zen, characterized by a decisive shift away from gradualist approaches to enlightenment and toward the idea of sudden awakening, accessible to all regardless of education or background.

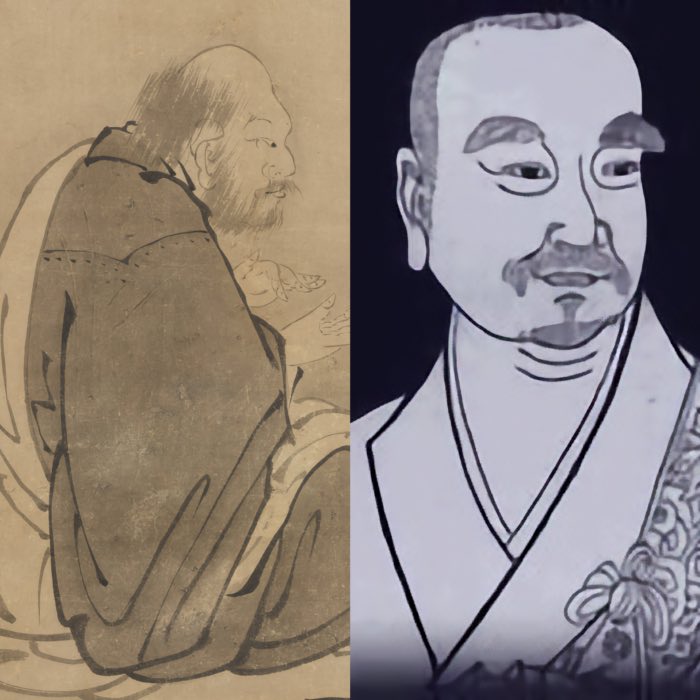

The sixth patriarch tearing a sutra, ink wash painting, Song Dynasty (960–1279), China. Depicted is a pivotal moment in the legendary life of Huineng (638–713), the Sixth Patriarch of Chinese Chán (Zen) Buddhism. According to tradition, Huineng, an illiterate layman, astounded a monastic assembly by arguing that true understanding of the Dharma does not depend on textual study but on direct, intuitive insight into one’s own mind. In this radical gesture — symbolically tearing a Buddhist sutra — Huineng challenges the primacy of scriptural learning, emphasizing instead the immediacy of awakening beyond words and letters. The act illustrates a foundational Zen principle: that ultimate truth cannot be grasped through texts alone, but must be realized directly in lived experience. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) (modified)

Huineng’s rise to prominence also marks a critical moment in the institutional history of Chán, as the lineage split between Northern and Southern interpretations. His story, whether taken as legend, history, or both, stands as a powerful narrative of anti-elitism, immediacy, and direct realization. In this post, we explore Huineng’s historical and legendary life, his teachings, the influence of the Platform Sūtra, and the broader impact of his legacy on the direction of East Asian Zen.

Historical and legendary biography

Huineng’s life is primarily known through the Platform Sūtra of the Sixth Patriarch (Liùzǔ Tánjīng), a text compiled decades after his death and one of the most important documents in the entire Zen tradition. The biographical narrative presented there blends history, hagiography, and doctrinal polemic.

Huineng was born in 638 in Guangzhou in southern China into the Lu family. After the early death of his father, he supported his mother by collecting and selling firewood. He was never formally educated and remained illiterate throughout his life. One day, while delivering firewood to an inn, he overheard a guest reciting the Diamond Sūtra and experienced a moment of profound awakening. After ensuring his mother’s well-being, he set out to seek a teacher of the Buddha Way.

Eventually, Huineng arrived at the monastery of the Fifth Patriarch, Hongren, who assigned him work in the kitchen where he hulled rice and gathered firewood. Despite his humble background and lack of formal education, Huineng’s spiritual insight impressed Hongren. When the time came to determine his successor, Hongren challenged the monks to express their understanding in verse.

Shenxiu, the senior monk, composed the following gāthā:

The body is the Bodhi tree,

The mind a standing mirror bright.

Polishing it diligently,

Let no dust alight.

Hongren praised this verse but noted that it revealed only an initial understanding. Hearing this verse recited in the monastery, Huineng, still an unrecognized worker, composed his own gāthā and had it written on the wall:

Originally there is no Bodhi tree,

Nor a mirror standing bright.

Since all is empty from the beginning,

Where could dust alight?

Hongren immediately recognized the depth of Huineng’s understanding. To avoid jealousy and sectarian conflict, he erased the verse and summoned Huineng by night. In secret, he transmitted to him the robe and bowl of patriarchal succession, declaring him the Sixth Patriarch. He instructed Huineng to hide for a time and later bring the Dharma to the people of the South.

Huineng went into hiding for several years before beginning to teach publicly, especially at Baolin Monastery in Caoxi, where he attracted a wide following. He passed away in 713 CE. His teachings and the school that grew around him, later called the Southern School of sudden enlightenment, came to dominate the development of Zen in China and beyond.

Teachings and the philosophy of sudden awakening

Huineng’s teachings are revolutionary in their redefinition of practice, realization, and the very nature of awakening. He argued that enlightenment is not something gradually attained through effort, purification, or study, but rather an immediate recognition of one’s already-pure mind. This view contrasts sharply with earlier forms of Buddhist training that emphasized gradual cultivation.

Huineng also challenged the authority of scriptural knowledge and ritual observance. He claimed that awakening is not confined to monastics or scholars, but available to anyone who turns inward. In this way, he emphasized formless practice over form-based ritual, direct perception over doctrinal elaboration.

Non-thought, non-attribute, and non-abiding

According to the Platform Sūtra, Huineng’s key teachings are often summarized under three interrelated concepts: no-thought (wúniàn), non-attribute (wúxiàng), and non-abiding (wúzhù).

No-thought does not mean the absence of thought altogether, but refers to a state of deep attentiveness that is unentangled and unobstructed. Huineng taught that thought itself is not a problem — it is attachment to thought that creates delusion. As he explained:

Thoughtlessness is to see and to know all dharmas with a mind free from attachment. When in use it pervades everywhere, and yet it sticks nowhere… But to refrain from thinking of anything, so that all thoughts are suppressed, is to be dharma-ridden, and this is an erroneous view.

Rather than suppress mental activity, Huineng instructed practitioners to observe the mind as it is — to see how thoughts arise and fall like mirages — and to avoid becoming entangled in them. In his words, “Freedom from thought means having no thought in the midst of thoughts.”

Non-attribute, closely related to no-thought, refers not to a denial of sensory or phenomenal characteristics, but to a way of engaging them without fixation. Huineng affirms the world of attributes while simultaneously teaching detachment from them. He compares our self-nature to space, saying:

The illimitable void of the universe is capable of holding myriads of things… Space takes in all of these, and so does the voidness of our nature.

To embrace all appearances without clinging to them is to live with equanimity. This teaching affirms a this-worldly orientation and resonates with indigenous Chinese perspectives that value relational and dynamic views of reality.

Non-abiding completes the triad. Huineng teaches that liberation comes from flowing through experience without attachment to any moment — past, present, or future:

Within each moment of experience, not to think of any previous state… to go through each experience without dwelling in it, that is freedom from bondage. This is why nonabiding is the root.

Unlike earlier Buddhist models that often emphasize stillness and quiescence, Huineng presents a dynamic vision of enlightenment as flow. As Brook Ziporyn observes, Huineng’s spacelike self-nature is not inert, but “a kind of hyperintense motion.” He affirms transformation, saying:

Good friends, one’s enlightenment must flow freely. How could it be stagnated? When the mind does not reside in the dharmas, one’s enlightenment flows freely… If you say that always sitting without moving is it, then you’re just like Śāriputra meditating in the forest, for which he was scolded by Vimalakīrti!

These core teachings — no-thought, non-attribute, and non-abiding — together express a uniquely fluid, dynamic, and non-dualistic view of practice and realization. They remain foundational for later Zen philosophy across East Asia.

Meditation and wisdom

Another defining feature of Huineng’s teaching is his non-dualistic view of meditation (dhyāna) and wisdom (prajñā). In contrast to schools that treat meditation as a preparatory stage leading to wisdom, Huineng insists that the two are inseparable and mutually inclusive. He famously states that to consider one as preceding the other would be to give the Dharma two characteristics.

For Huineng, wisdom is the function of meditation, and meditation is the essence of wisdom — an essence-function relationship. Just as a lamp and its light exist simultaneously (with the lamp as essence and light as function), so too do meditation and wisdom. This simultaneity underscores Huineng’s perspective that awakening is already present and need not be attained through a sequence of stages.

Huineng’s unification of meditation and wisdom implies a sudden approach to practice, rejecting the notion that meditation is a means to a future realization. Such dualistic thinking, Huineng argues, obscures the truth that awakening is immediate and always accessible, not a distant goal to be attained in time.

Dhyāna

Huineng also reinterpreted the practice of seated meditation (zuòchán) in a distinctly non-literal way. He defined “sitting” (zuò) not as physical stillness, but as the mind not being activated by external distinctions of good and bad. “Meditation” (chán), then, is the clear internal perception of the motionless nature of self. For Huineng, it was not bodily posture that mattered, but how one related to mind and awareness.

He criticized practices that focused on stillness, concentration on mind, or pursuit of inner purity. Such efforts, he explained, often reinforce dualistic thinking. As he put it:

If one is to concentrate on the mind, then the mind [involved] is fundamentally false. You should understand that the mind is like a phantasm, so nothing can concentrate on it. If one is to concentrate on purity, then [realize that because] our natures are fundamentally pure, it is through false thoughts that ‘suchness’ is covered up. Just be without false thoughts and the nature is pure of itself. If you activate your mind to become attached to purity, you will only generate the falseness of purity.

According to Huineng, this kind of objectification — making mind or purity into an object of meditation — leads to delusion. Rather than reveal the pure nature, it conceals it. According to this perspective, our nature is inherently pure, but activating the mind in pursuit of purity externalizes and obstructs that realization.

In place of structured concentration and conceptual purity, Huineng advocated effortless, non-abiding awareness: a state in which mind neither clings nor resists, but flows freely, unobstructed by form, effort, or goal.

The Platform Sūtra and its influence

The Platform Sūtra is the key textual source for Huineng’s teachings and the only Chán scripture attributed to a Chinese patriarch. Composed likely in the mid-8th century by followers of Huineng, the text blends personal biography, doctrinal exposition, and records of public sermons.

Among its central themes are the unity of meditation and wisdom, the inherent Buddha-nature of all beings, and the rejection of distinctions between lay and ordained, learned and unlearned. It famously proclaims that “meditation and wisdom are of one essence,” asserting that true insight is not a product of study but of direct realization.

The text had profound influence across East Asia, especially in the shaping of Korean Seon, Japanese Zen, and Vietnamese Thiền. Its rhetorical and doctrinal opposition to gradualism set the tone for centuries of debate within the Zen world, particularly in contrast to the teachings associated with Shenxiu and the Northern School.

Legacy and broader impact

Huineng’s importance in the Zen tradition cannot be overstated. He is revered not only as the Sixth Patriarch but as the one who clarified and made accessible the radical essence of Zen. His emphasis on sudden awakening democratized spiritual realization, allowing Zen to move beyond the monasteries and attract a wider social following.

The division between the so-called Northern and Southern Schools, though later exaggerated for sectarian reasons, reflects real differences in emphasis — gradual versus sudden, form versus formlessness. While later scholarship has questioned the historical basis of this dichotomy, it is clear that Huineng’s approach prevailed in shaping the mainstream of Zen’s identity.

His legacy lives on not only in texts and lineages, but in the ethos of Zen itself: non-attachment, immediacy, and the conviction that enlightenment is here and now, if only one sees clearly.

Conclusion

Dajian Huineng’s life and teachings mark one of the most significant turning points in the history of Chán (Zen) Buddhism. Through both his personal story and the doctrinal innovations preserved in the Platform Sūtra, Huineng catalyzed a transformation in how enlightenment was understood, practiced, and transmitted.

At the heart of his vision was the insistence that awakening is sudden, not the result of gradual effort or doctrinal study, but the immediate recognition of one’s already-pure nature. This core insight — radical in its time — redefined the parameters of Buddhist practice. By teaching non-thought, non-attribute, and non-abiding, Huineng placed emphasis not on escaping the world, but on realizing the true nature of mind in the midst of everyday life. Meditation and wisdom, in his view, were not separate steps but two facets of the same reality. His reinterpretation of meditation emphasized fluid, non-dual awareness over fixed form or conceptual purity.

Critically, Huineng’s role in challenging established norms extended beyond philosophy. His rise as a largely uneducated southerner in a monastic hierarchy dominated by elite literati made him a symbol of anti-elitism and inclusivity. His teachings resonated across East Asia precisely because they transcended institutional boundaries and spoke to a universal human capacity for awakening.

While modern scholarship has shed light on the constructed nature of some aspects of Huineng’s biography and the Northern–Southern School dichotomy, the enduring power of his message remains. His rejection of rigid practice and advocacy of immediate, non-attached awareness laid the groundwork for what Zen would become: a tradition rooted in direct experience, iconoclasm, and the liberation of mind from conceptual entanglements.

In this way, Huineng did not found something new apart from Buddhism — he reinvigorated its central concern with liberation, bringing it closer to Siddhartha Gautama’s original insight that freedom lies not in metaphysical speculation, but in seeing reality as it is. His legacy continues to shape the core ethos of Zen: uncompromising clarity, immediacy, and trust in the selfless nature of mind.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

comments