Zen’s way of knowing: From conceptual thought to direct realization

Zen (Chán) Buddhism places a radical emphasis on direct, non-conceptual realization of reality. Unlike the analytic, scholastic traditions found in some schools of Indian and Tibetan Buddhism, Zen centers on awakening that occurs beyond words and letters (教外别传, jiàowài biéchuán), through intuitive insight into one’s true nature. This epistemological orientation links Zen to Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka philosophy and its deconstructive critique of conceptual elaboration (prapañca). But Zen moves beyond critique into praxis: it seeks not to defeat concepts for their own sake, but to open the practitioner to a different kind of knowing altogether.

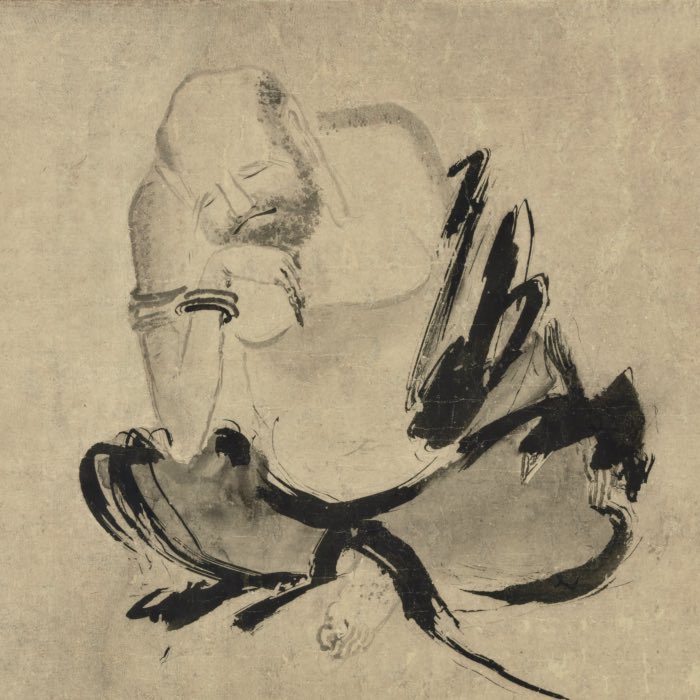

Ensō (“Zen circle”) calligraphy by Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh, 2015. In Zen, the ensō symbolizes enlightenment, the universe, and the void. It is often painted in a single brushstroke, embodying the idea of non-duality and the interconnectedness of all things. The circle can be open or closed, representing the cyclical nature of existence and the balance between form and emptiness. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Chinese phrase wàijiào biéchuán (外教别传) literally means “a separate transmission outside the scriptures” or “a special transmission beyond the teachings.” It is most famously associated with Zen (Chán) Buddhism and expresses one of its core self-understandings:

A special transmission outside the scriptures;

Not relying on words and letters;

Directly pointing to the human mind;

Seeing one’s true nature and becoming Buddha.

(外教别传,不立文字,直指人心,见性成佛)

Here, 外教 (wàijiào) refers to “external teachings” or scriptural learning, while 别传 (biéchuán) signals a “separate transmission” — the direct, often wordless, communication of awakening from master to student. This underscores Zen’s emphasis on direct experience and realization over scholasticism or doctrinal formulation.

In this post, we explore the epistemology of Zen as a unique mode of Buddhist insight. It traces the shift from conceptual cognition (vijñāna) to direct knowing (prajñā), highlights key contrasts with discursive methods, and considers how Zen’s “non-knowing” (不知, bù zhī) functions not as ignorance but as awakened awareness.

From conceptualization to prajñā

In mainstream Mahāyāna Buddhism, especially in the Prajñāpāramitā (Perfection of Wisdom) literature, prajñā (wisdom) is regarded as the faculty of direct, non-dual insight that sees through the illusions of conceptual thought. Unlike vijñāna (discriminative consciousness), which divides experience into subject and object, prajñā sees things as they are — empty of inherent essence and arising dependently. This teaching is further developed in Madhyamaka philosophy founded by Nāgārjuna, which systematically deconstructs all conceptual views to reveal their emptiness (śūnyatā). For Nāgārjuna, liberation is not achieved by acquiring true concepts, but by letting go of all views — including Buddhist ones — recognizing their lack of intrinsic substance.

Zen inherits these insights and deepens them in praxis. It does not merely critique conceptuality but seeks to cut through it entirely. Rather than constructing philosophical arguments, Zen turns to silence, paradox, and direct experience. This makes it not irrational but trans-rational: it transcends the limitations of discursive reasoning and opens a path toward prajñā as lived, embodied wisdom. Central to this is the Zen phrase seeing into one’s nature (见性, jiànxìng, Japanese: kenshō). This phrase, literally meaning “to see one’s [true] nature”, refers to the sudden, direct realization of one’s original mind — pure, unconditioned, and empty of fixed identity. It is not a mystical essence but an experiential insight into the selfless and impermanent flow of mind and reality.

Modes of knowing: Not Two, Not One

The phrase “Not Two, Not One” captures a key dimension of Zen epistemology: it denies the absolute division between knower and known (not two), while also rejecting any naïve oneness that collapses differentiation entirely (not one). True knowing in Zen transcends binary thinking without erasing lived experience. It points to a mode of perception that is radically immediate, in which distinctions are not fixed, but fluid and contingent.

Zen does not simply oppose conceptual knowledge with a mystical alternative. Instead, it reframes the entire structure of knowing. Where conventional knowledge is objectifying and reliant on dualities, Zen insists that true knowing is non-dual: it is a mode of awareness in which subject and object, knower and known, dissolve into immediacy. This mode is not abstract, but radically intimate.

In kōan encounters, for example, students are not asked to solve riddles intellectually, but to experience the collapse of dichotomous thought. When a master shouts, “Mu!” or declares, “Three pounds of flax!”, the point is not semantic. It is performative. It interrupts habitual cognition, allowing the student to glimpse a reality that is not mediated by concepts.

Such knowing is often described in Zen as no-mind (無心, wúxīn, Japanese: mushin), no-thought (無念, wúniàn, Japanese: munen), or “don’t-know mind” (不知, bù zhī, Japanese: fuchi). This is not a void of ignorance, but a clarity unclouded by fixation. As Linji Yixuan put it, “Just put down the myriad entangling conditions, and your original nature will appear.”

Practice as epistemology

Zen practice — especially zazen (seated meditation) — is epistemological (that is, related to how we know what we know and the nature of knowledge, in contrast to to metaphysics, which deals with the nature of reality itself) in its intent. It is not a concentration exercise aimed at tranquility for its own sake, but a way of unlearning. Through sustained sitting and present-moment awareness, the mind begins to disengage from its compulsive patterning. As the mind quiets, a deeper clarity emerges — one not constructed, but inherent.

This is why Zen often speaks of awakening rather than learning. The truth is not something to be acquired; it is to be directly realized, or better: directly encountered. This encounter does not require intellectual elaboration but sincerity, attentiveness, and radical openness.

Zen’s Challenge to Epistemology

In this light, Zen does not reject reason, but situates it within a broader horizon. It challenges modern epistemological assumptions: that knowledge is always propositional, representational, or transferable. Instead, Zen suggests that the most profound knowledge is embodied, non-transferable, and ineffable. It is something one must taste for oneself.

This is not anti-intellectualism. Great Zen masters were often deeply educated. Rather, Zen insists that real insight cannot be conveyed through texts or syllogisms alone. As the famous Zen saying goes, “A picture of a rice cake does not satisfy hunger.”

Conclusion

Zen epistemology presents a radical challenge to conventional understandings of knowledge. While much of Buddhist thought acknowledges the limitations of conceptualization, Zen transforms this critique into a lived practice of non-conceptual knowing. It is grounded not in the accumulation of ideas, but in a direct, embodied, and non-dual awareness — what it calls seeing one’s true nature (见性, jiànxìng, Japanese: kenshō). Rather than pursuing a linear path from ignorance to insight, Zen assumes that awakening is already present; the task is not to acquire something new, but to strip away the obscurations that conceal what is already the case.

In doing so, Zen offers a unique epistemological stance that differs significantly from both other Buddhist schools and Western traditions. In contrast to the often scholastic and text-centered approaches of Indian and Tibetan Buddhism, Zen embraces immediacy and performance — its use of kōans, paradoxes, and silence disrupts habitual cognition and invites a different mode of knowing. While Western epistemology typically seeks certainty, reproducibility, and clarity, Zen centers on insight that is transformative but incommunicable, verified only through direct experience. This does not mean Zen lacks rigor; rather, its rigor lies in disciplined attention, unflinching honesty, and sustained inquiry beyond the realm of language.

Zen’s way of knowing thus functions as a corrective to over-reliance on conceptual thinking. The human mind, when left untrained, tends to equate understanding with accumulation — especially in an age of information overload, Zen reminds us of a different possibility: that wisdom may lie not in knowing more, but in knowing less — in unknowing, in attending deeply, and in directly encountering the moment as it is.

This directness, however, is not unique to Zen alone. Other Buddhist traditions also, such as Yogācāra, early Theravāda, and Vajrayāna, emphasize prajñā (wisdom) as a form of direct insight, and even the Western philosophical tradition has currents — such as phenomenology and existentialism — that explore lived immediacy over abstraction. Yet Zen distinguishes itself through the intensity and singularity with which it commits to non-duality and the immediacy of practice as the path of knowing. It cultivates a form of realization that is not dependent on dogma, authority, or systematic knowledge, but on direct, intimate encounter with the nature of mind and world.

As we compare traditions and reflect on the role of Zen, it becomes apparent that its epistemology offers a distinct, practice-based alternative to both scholastic Buddhism and Western rationalism. Its emphasis on lived insight over theoretical formulation, and on unknowing as a gateway to wisdom, remains a powerful and timely counterpoint to dominant models of knowledge in the modern world.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Prajna, Zen und die Höchste Weisheit, Die Verwirklichung der „transzendenten Weisheit“ im Buddhismus und im Zen, 1. Januar 1990, O. W. Barth, ISBN-10: 3502645981

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

comments