The central element of Zen: Zazen

Zazen, literally “seated meditation”, is not merely one technique among others in Zen; it is the very heart of its path. More than a means to an end, it embodies the entirety of the Zen approach: direct, immediate, and grounded in the here and now. Zen does not prioritize reading scriptures, performing rituals, or climbing hierarchical stages of attainment. Instead, it points us to reality as it is, and asks us to sit down and meet it.

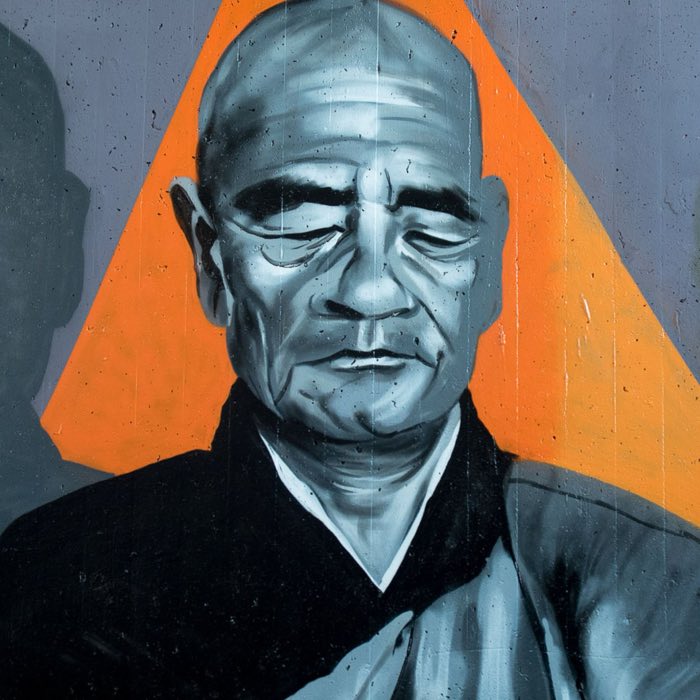

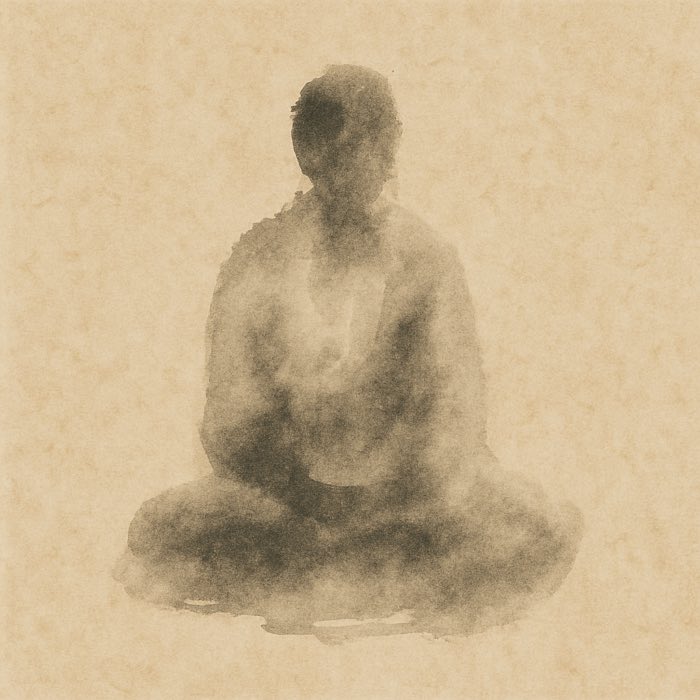

Kodo Sawaki in Zazen (1920) sitting in Zazen. His eyes are closed, his legs crossed, and his hands from a so-called gasshō (合掌) position. His mind is focused on the present moment, free from distractions. This posture embodies the essence of Zazen: a deep connection to the body and the breath, a stillness that allows for the unfolding of reality as it is. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Why sitting? Because zazen strips away distractions. In stillness and silence, the usual dramas of goal-setting, striving, and self-definition begin to fall away. We return to the body, the breath, the ground beneath us. In this simplicity, we come face to face with suchness (tathatā) — the unfiltered presence of things, free from projection and resistance. Zazen is not about producing insight; it is insight embodied. Not about chasing enlightenment, but realizing it was never absent.

Thus, sitting becomes the most radical act: to do nothing, to go nowhere, to be fully present. And in this presence, Zen teaches, everything is revealed.

Historical roots of Zazen in Zen

Zazen, though famously associated with Japanese Zen, has its roots in much earlier Buddhist meditation traditions. In early Indian Buddhism, meditative practices such as dhyāna (Pāli: jhāna) were central to the path of liberation. These were states of deep concentration and absorption cultivated by the historical Siddhartha Gautama himself. The emphasis was on calming the mind, observing inner phenomena, and eventually transcending conceptual dualities.

When Buddhism entered China in the early centuries CE, these Indian forms of seated meditation encountered native Daoist sensibilities and Chinese philosophical frameworks. The emerging tradition of Chán (Zen) Buddhism began to adapt meditative discipline into a new form — less focused on methodical absorption and more directed toward direct insight. Bodhidharma, the legendary first patriarch of Chinese Chán, is credited with re-centering the tradition on meditative practice and “wall-gazing” (bìguān), a term evoking both literal seated stillness and inward-looking contemplation. While the exact nature of Bodhidharma’s practice remains unclear, the symbolic meaning is powerful: a direct, non-conceptual turning toward the mind.

This orientation would find its most radical expression in the teachings of Eihei Dōgen (1200–1253), the founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan. After studying in China and returning to Japan, Dōgen emphasized a form of meditation he called shikantaza (只管打坐), or “just sitting.” Unlike earlier meditative traditions that used meditation as a means to attain insight or specific mental states, Dōgen declared that sitting itself is awakening. For Dōgen, practice and realization are not two. One does not sit in order to awaken; one sits as awakening.

The practice of Zazen

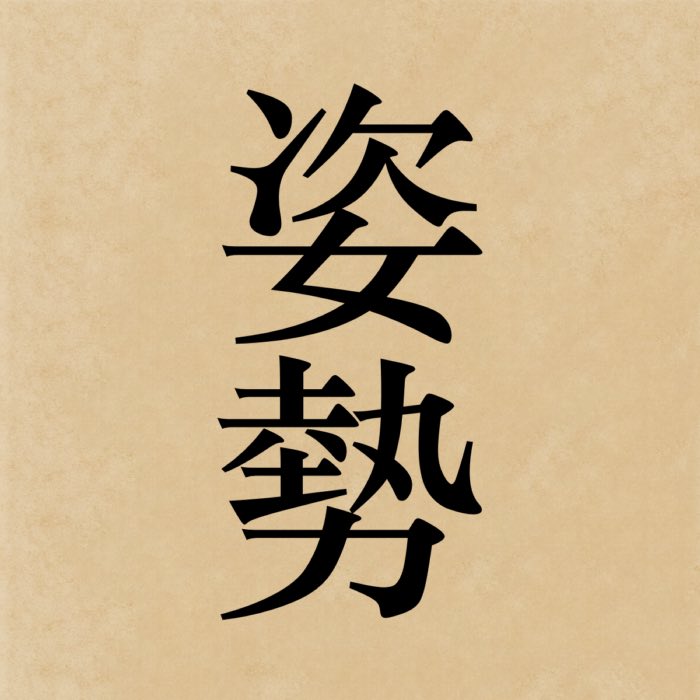

Zazen begins with the body. The practitioner takes a stable seated position, often in lotus or half-lotus posture, with the spine upright and the hands placed in the cosmic mudra — right hand cradling the left, thumbs lightly touching, forming an oval that rests just below the navel. The eyes are half-open, softly resting on a point before them, and the breath flows naturally, without control or force. This physical stillness is not incidental: it grounds the practice in the reality of embodiment.

In Zen, the body is not a vehicle for the mind or a passive recipient of instruction — it is the very site of awakening. The act of sitting still is itself a kind of wisdom, revealing the movements of the mind not through analysis, but through the contrast with silence. One begins to notice the subtlest patterns of grasping, distraction, and resistance, not in order to suppress them, but simply to see them, and let them pass. This seeing arises not from thinking, but from presence.

Zazen embodies the principle of non-doing — wuwei, as known in Daoist philosophy. There is nothing to attain, nothing to achieve. One sits not to become something other than what one is, but to fully be. In this sense, zazen is radical receptivity: a return to suchness, to reality as it is, without resistance, without embellishment. It is through this radical simplicity that the practitioner comes to realize that awakening is not elsewhere, but always already here — discovered, not acquired.

Practicing Zazen

The practice of zazen is deceptively simple, yet it requires a deep commitment to presence. It is not about achieving a particular state of mind or cultivating specific qualities. Instead, it invites the practitioner to be fully present with whatever arises in the moment — thoughts, sensations, emotions — without clinging or aversion.

Even with correct posture, zazen is not simply a matter of sitting still. If the mind wanders and becomes absorbed in thoughts, one is not truly practicing zazen — one is simply thinking while seated. Likewise, if sleepiness overtakes the body, one is merely dozing. Zazen is neither reverie nor drowsiness. It is an active, living posture — one that embodies wakefulness, vitality, and total presence.

The energy of zazen must be balanced: not slack and lifeless, but also not strained or rigid. When we drift into dullness, our posture collapses; when we chase thoughts, the body tenses. True zazen expresses life most purely — condensed, awake, and present in its rawest form. It is easy to talk about this, but difficult to actualize. That is why the practice requires a wholehearted commitment, a steering of one’s entire being — body, breath, and awareness — into the direction of true sitting.

The following guidelines can help establish a solid foundation for zazen practice. They are taken from Kōshō Uchiyama’s book Weg zum Selbst: Zen-Wirklichkeit (1973), which offers a clear and practical approach to zazen. They mostly reflect Dōgen’s teachings Fukanzazengi (普勧坐禅儀), a text that outlines the essential elements of zazen practice.

Creating the space

The practice of zazen begins with the environment. Choose a quiet space that is neither too bright nor too dark, warm in winter and cool in summer. Keep the room free from wind, smoke, and distractions, and maintain it in a clean and orderly state. This cultivates an atmosphere of peace — stable and conducive to deep sitting. If possible, designate this place as a regular meditation spot.

You may place a small statue of the Buddha, fresh flowers, and light incense. These are not objects of worship, but symbols of stillness, compassion, and presence. Upon entering the space, bring your palms together in gasshō (合掌) to show respect for the practice and the place that hosts it.

Arranging the posture

- Use a zafu (a firm round cushion) placed on a zaniku (a padded mat or zabuton).

- Sit on the forward third of the zafu. Your knees should firmly contact the mat, forming a stable tripod with your seat.

- Choose the full lotus position (right foot on left thigh and vice versa) if possible; otherwise, the half-lotus or Burmese position is fine.

- Sit upright, spine extended, chin slightly tucked, and crown of the head pressing gently upward — as if touching the ceiling.

- Let the shoulders relax and the ears align with them.

- The nose should align vertically with the navel.

- Place the hands in the cosmic mudra, resting in the lap with thumbs lightly touching.

- Keep the eyes open, gently lowered and unfocused, with a soft gaze toward the wall or floor.

The importance of this posture cannot be overstated. Unlike slouched or contracted positions that foster tension and rumination — like the figure in Rodin’s famous sculpture ‘The Thinker’, hunched forward, lost in thought — the Zazen posture is open, upright, and balanced. In sitting this way, the body releases unnecessary tension, the blood flows downward from the overstimulated head to the grounded abdomen, and the mind naturally settles. This physical arrangement makes it difficult to remain entangled in fantasies or anxieties. Thus, the posture itself supports the letting-go that is at the heart of Zazen.

Beginning the sitting

- Open your mouth briefly and exhale fully to reset your body-mind state.

- Rock side to side a few times to release tension, then settle into stillness.

- Breathe quietly through the nose. Let short breaths be short, long ones be long — there is no control here, only observation.

- Allow the breath to settle naturally in the tanden (丹田) — a point about three centimeters below the navel, considered the body’s energetic and grounding center.

-

Do not force or analyze the breath. As one modern interpretation of Dōgen’s instructions in the Shōbōgenzō suggests:

The breath goes into the abdomen — do not try to know from where. It comes out again — do not try to know where it goes. Let it be. The breath itself is neither long nor short.

While not a direct quote, this reflects Dōgen’s emphasis on natural breathing without control or fixation, and the importance of allowing the breath to settle in the tanden without conceptual interference.

This posture and approach are not just formalities. They embody presence and receptivity — awakening through form without clinging to it.

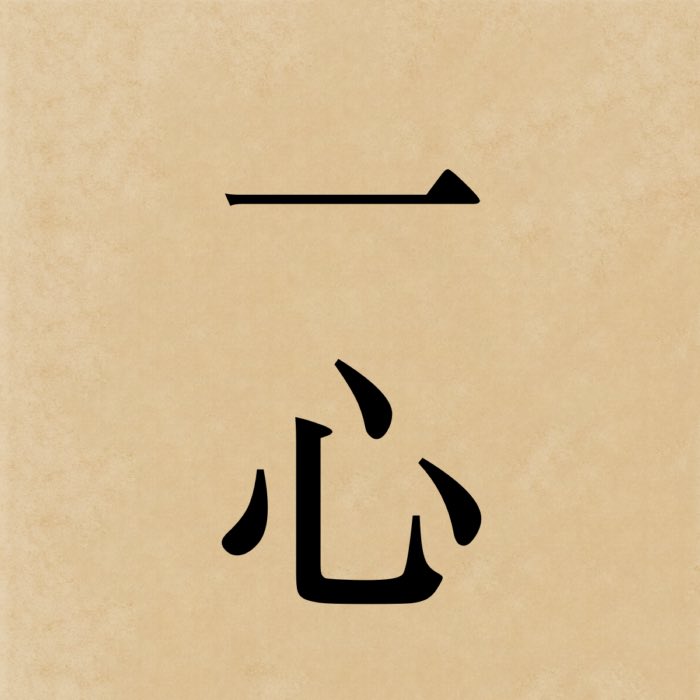

Once the body has assumed the correct posture and the breath begins to flow naturally, the heart settles. The breath is drawn gently into the lower abdomen and returns from it, not forced but arising spontaneously. Though inhalation and exhalation may differ, both are rooted in the same center — the tanden. Even if the breath is initially unsettled, through consistent posture and breathing, the heart-mind (心, shin) calms on its own.

On dealing with thoughts during Zazen

A common concern is whether zazen requires a complete absence of thought. Does a wandering mind mean one has failed at zazen? Not necessarily. The key is to distinguish between three things: having thoughts, chasing thoughts, and being lost in thoughts. It is entirely natural for thoughts to arise — we are living beings, not inert stones. Even if you sit motionless like a rock, thoughts will occur. What matters is whether you grasp at them.

Zazen does not require the absence of all thoughts, but the refusal to follow them. Let the thoughts fall away. When a thought arises — “a flower”, for instance — it holds no power unless it is followed by another thought like “it is beautiful.” If not continued, it loses all weight and dissolves on its own. This is what Dōgen calls “the thinking of non-thinking” (hishiryō): awareness without attachment. The posture itself supports this. With blood flowing downward and the body settled, associative thinking quiets, and the “free fall of thoughts” becomes possible. One sits in wide openness, hands, mentally speaking, holding nothing.

Kinhin: Walking meditation

While zazen is the core practice of Zen, it is traditionally complemented by kinhin, or walking meditation. Practiced between periods of sitting, kinhin serves to harmonize stillness with movement and to extend meditative awareness into action. The principle remains the same: being fully present.

In kinhin, the practitioner walks slowly, step by step, usually in a circle or along a path, with hands held in a specific mudra — often left hand closed in a fist and right hand enclosing it, resting at the solar plexus. Each step is synchronized with the breath, and the eyes are lowered, maintaining the same soft gaze as in zazen. Movement is deliberate, unhurried, and fully embodied.

Kinhin is not a break from meditation, but meditation itself — in motion. It allows the body to stretch, the blood to circulate, and the mind to maintain continuity of awareness. Just like sitting, walking becomes an expression of non-doing. The aim is not to arrive anywhere, but to be completely present with each step. As such, kinhin trains the practitioner to carry the stillness of zazen into the activity of everyday life.

Shikantaza: Just sitting

Within the broader practice of zazen, one form is particularly emphasized in the Sōtō Zen tradition: shikantaza, often translated as “just sitting.” Unlike other meditative forms that use breath-counting, visualizations, or mantras as aids to concentration, shikantaza is a pure form of open awareness. The practitioner does not aim to control or direct the mind in any particular way. Instead, one simply sits, with wholehearted presence, fully attentive to whatever arises, moment by moment.

Shikantaza is deceptively simple. Without a technique to master, there is nothing to “get right”, and yet it can be profoundly challenging precisely because the mind is so used to doing, evaluating, and striving. In shikantaza, every sensation, thought, or feeling is included, but not grasped. One does not try to push away distractions or cling to clarity — one simply allows everything to appear and disappear in its own rhythm.

This form of meditation echoes the Zen ethos that practice and realization are not two. There is no goal apart from the sitting itself. In that act of “just sitting”, the entire path is present.

The non-goal of Zazen: Awakening without attainment

A paradox lies at the heart of zazen: it is a practice without a goal, yet it is profoundly transformative. In most traditions, meditation is treated as a means to an end — calmness, insight, liberation. In Zen, zazen resists this instrumental logic. It is not practiced to attain enlightenment, but to express the very enlightenment that is already present.

From the Zen perspective, kenshō (見性; Japanese: seeing one’s true nature) or satori (悟り; Japanese: awakening) are not things to be achieved but awakenings to what has always been the case. The practice of sitting is itself the realization of buddhahood. One does not sit to become a Buddha; one sits as a Buddha. This radical non-duality collapses the usual divide between seeker and sought, between practice and fruition.

In this way, zazen offers an experiential entry point into the core teachings of Mahāyāna Buddhism: tathatā (suchness), śūnyatā (emptiness), and dependent origination. The practitioner comes to see the nature of reality not through abstract doctrine, but by dwelling silently in its unfolding. Form is emptiness; emptiness is form — not as theory, but as the direct and vivid reality of each breath, each sensation, each passing thought.

Zazen is not a method that leads somewhere else. It is the unfiltered immediacy of here and now. In sitting without grasping, resisting, or analyzing, the practitioner stops fleeing reality and begins to dwell in it completely. That is the heart of Zen.

Zazen also dismantles our habitual way of thinking in terms of goals and achievements. It is not a path with a measurable endpoint. One may sit for years and never be able to say, “Now I have reached it”. And if one does say so, that very thought signals a fall away from true zazen. The one who sits simply sits — not knowing whether they are attaining or failing, only continuing.

In this way, zazen becomes the practice of relinquishing all self-measurement. It is the Self building the Self into the Self, a movement that can never be grasped from the outside. One must entrust the body to the practice, not the calculating mind. With every breath, we let go of striving, judgment, and self-consciousness.

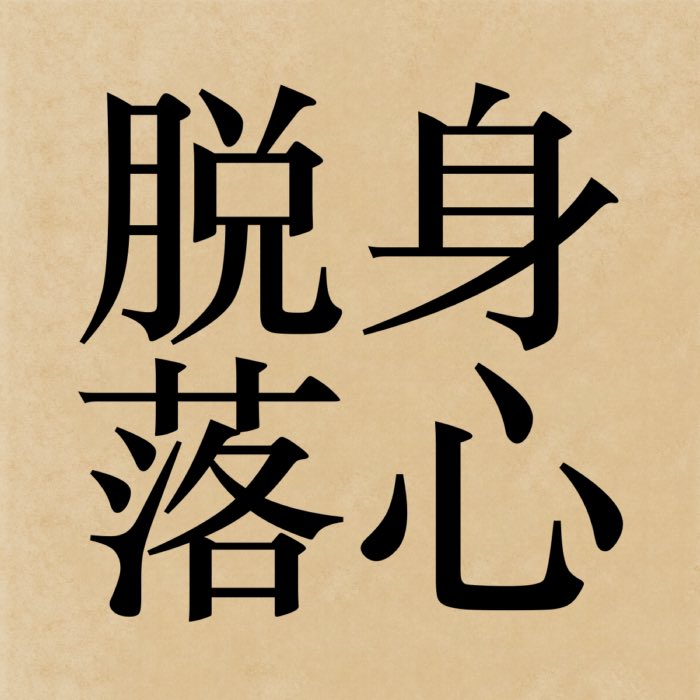

This is why Dōgen speaks of “dropping off body and mind” (shinjin datsuraku) — not as a metaphor, but as the lived reality of full presence. Zazen is not done for a purpose beyond itself. Zazen does zazen. To sit is to enact awakening itself, not to pursue it. This is what makes it the most distilled expression of life in its purest, most awakened form.

As Dōgen quotes his teacher Tiantong Rujing:

To sit with legs crossed has always been the posture of the Awakened. If you entrust your body to the sitting of Zen, you will drop off body and mind.

Insight into mind and reality

Zazen is not merely a discipline of sitting, it is an invitation to see directly into the nature of mind and reality. In this stillness, one does not engage in analysis or deduction, but learns to observe the ever-changing flow of thoughts, emotions, and perceptions. Through this silent witnessing, the practitioner gradually uncovers the non-substantial, transient nature of all mental activity.

This direct seeing echoes the Zen principle of kenshō, the recognition of one’s true nature. Yet this “true nature” is not a self or substance, but the very absence of fixed essence: mind as empty, luminous, and ungraspable. What remains is tathatā, suchness – the world as it appears when seen without conceptual overlay. Reality is not constructed by the mind, nor separate from it. It arises as a seamless field of interdependence, appearance, and disappearance.

Zazen thus becomes a way of encountering śūnyatā not through doctrine but through experience. The practitioner does not understand emptiness as a theory but feels its truth in every arising and passing moment. No thought or perception stands alone; everything is connected, contingent, and momentary.

This is also the insight into dependent origination and non-duality: the realization that all things arise together and vanish together, with nothing permanent or isolated. From this vantage point, there is no self separate from the world, no observer apart from what is observed. Suchness (tathatā) is not something behind or beyond things — it is the way things truly are.

Zazen is the direct encounter with that truth. It does not aim to explain reality, but to let it reveal itself. In the clarity of presence, one begins to see that awakening is not something to find, but something to stop ignoring.

Misunderstandings about Zazen

Despite its simplicity, zazen is frequently misunderstood, both by newcomers and by those outside the tradition. A common misconception is to equate zazen with escapism, relaxation, or trance. While the practice may bring calm, its aim is not to flee reality or achieve altered states. Zazen is the opposite of dissociation; it is radical engagement with the present moment in all its ordinariness.

Another misunderstanding is to treat zazen as a ritual or performance — a formalized sitting done to gain merit, fulfill obligation, or demonstrate discipline. In Zen, external form is never the point. The posture and setting support the practice, but they are not its essence. What matters is sincerity, presence, and the willingness to meet reality without filters.

Perhaps most significantly, zazen is not a technique to induce special states of mind. It is not about generating bliss, visions, or insights to be collected. In fact, the grasping for such states becomes an obstacle. Zazen is the practice of non-grasping. It teaches the practitioner to sit with whatever is: restlessness, boredom, joy, pain. Nothing is rejected, and nothing is pursued.

In this way, zazen is profoundly countercultural. It asks us to abandon striving, let go of self-improvement, and trust that the deepest truths are already here, waiting to be seen in the simplicity of sitting still.

Zazen in daily life

The essence of zazen does not end with the meditation cushion. It extends naturally into every aspect of daily life. Zen has long emphasized that true practice is not confined to formal sitting but includes all activities, however mundane. Every moment becomes an opportunity to embody presence.

This is what Dōgen means when he says that practice and realization are not two. Zazen is not preparation for awakening — it is awakening. Whether walking, cooking, working, or resting, the same mind that sits in zazen is available. The practice becomes seamless with life itself.

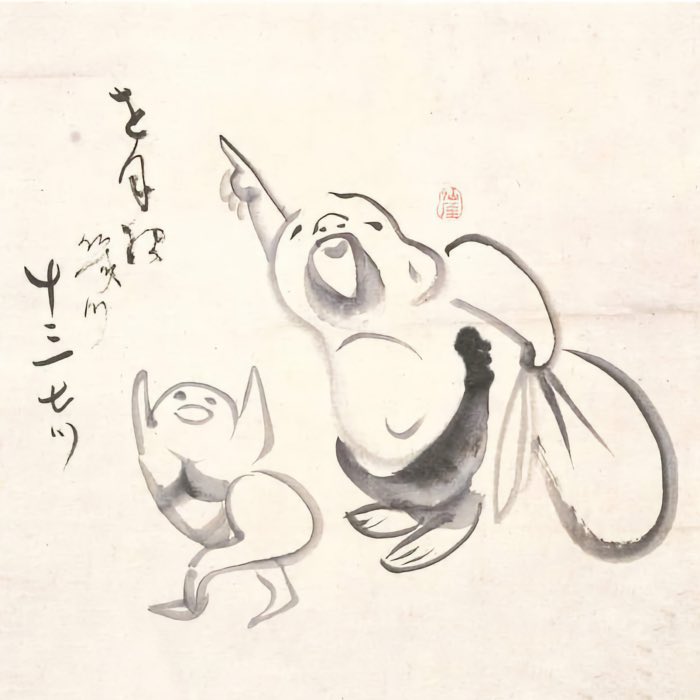

The famous Zen saying, “Before enlightenment, chop wood and carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood and carry water”, captures this spirit perfectly. Enlightenment does not remove us from the world; it reorients our relationship to it. The actions may remain the same, but the awareness within them transforms.

Zazen teaches us that every act, when performed with attention, humility, and non-grasping, becomes an expression of suchness. Thus, the goal is not to retreat from the world but to live within it fully, seeing clearly, and acting compassionately in each moment.

Zazen and the Zen community

Historically, zazen was practiced within the sangha, the monastic community that formed the heart of early Buddhist and later Zen practice. Sitting together in silence, following a shared schedule, and receiving guidance from a teacher were all considered essential to the training. In Zen monasteries, communal zazen (sōdō) became a central daily rhythm, reinforcing discipline, mutual support, and the non-verbal transmission of the Dharma. The shared silence of a zazen hall was not just about personal effort, but about cultivating a collective field of awareness and sincerity.

Practicing in a community still holds significant value today. The presence of others helps maintain motivation, exposes one to different stages of understanding, and creates a context in which the self is constantly mirrored, challenged, and supported. A teacher’s presence can offer crucial course corrections, preventing one from getting lost in subtle ego-traps or misunderstandings.

Yet in the modern world, not everyone has access to a Zen community or teacher. Many sincere practitioners are laypeople without monasteries nearby or without the possibility of joining regular zazenkais or retreats. Fortunately, this does not mean the path is closed. The essence of zazen remains fully accessible, even when practiced alone.

Zen history and teaching offer validation for lay practice. From the Sixth Patriarch Huineng (638–713), who was illiterate and awakened while still working as a laborer, to countless others who cultivated awakening outside the formal structures of the sangha, the message is clear: what matters most is sincerity, presence, and the willingness to sit down and face oneself.

For lay practitioners, regular sitting, even in solitude, can become a profound and steady path. Establishing a daily rhythm, dedicating a quiet space, and engaging with trustworthy written or recorded teachings can all support this practice. Occasionally attending retreats or finding a community online can provide additional structure and connection. But even without these, zazen remains what it always was: the silent return to reality, here and now.

In Zen, the truth is not monopolized by institutions or dependent on credentials. It appears wherever one sits wholeheartedly, drops striving, and allows the Dharma to reveal itself. Whether among many or alone, zazen remains a gateway into suchness.

Conclusion

Zazen stands as the foundational practice of Zen not because it delivers results in a linear sense, but because it is the clearest expression of Zen’s core insight: that awakening is not something to be reached, but something to be remembered, uncovered, and lived. Through sitting, one ceases chasing after states and instead meets the world without separation.

This non-dual immediacy is what distinguishes zazen from many other spiritual or meditative systems. Unlike practices that aim to refine the self, transcend the body, or attain altered states, zazen calls the practitioner into the very heart of experience — just as it is. That includes discomfort, boredom, joy, and ordinariness. Nothing is excluded. In this, zazen affirms the inherent dignity of the everyday.

Compared to other Buddhist schools that emphasize textual study, ritual, or sequential cultivation, Zen offers a radical simplicity: sit down and see. While not anti-intellectual, this path de-emphasizes discursive knowledge in favor of direct presence. Even in comparison to certain mindfulness traditions in the West, zazen differs in its resistance to goals, metrics, or techniques. Its wisdom lies in its refusal to depart from what is already here.

Zazen also shows its universality in the way it transcends institutional boundaries. While traditionally rooted in monastic life and supported by the Zen sangha, it remains fully available to lay practitioners, even those without access to a formal teacher or community. What matters is the sincerity of sitting and the willingness to return, again and again, to presence. Whether in a temple hall or a quiet room at home, the path of zazen remains unbroken.

Zazen embodies what it teaches. And what it teaches is not a doctrine, but a way of being that is open, silent, and awake. That is why Zen calls us to sit — not to escape, not to improve, but to realize that the deepest truth is already present, waiting patiently in stillness.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki (Autor), Jochen Eggert (Übersetzer), Zazen: Die Übung des Zen: Grundlagen und Methoden der Meditationspraxis im Zen, 1. Januar 1990, Herausgeber: O. W. Barth; 2. Edition, ISBN-10: 3502645957

- Dōgen, Eihei, Shōbōgenzō, 1243, Shōbōgenzō Kōkyōshū

- Dōgen, Eihei, Fukanzazengi, 1227

- Kōshō Uchiyama, François-Albert Viallet, Kōshō Uchiyama, Weg zum Selbst: Zen-Wirklichkeit, 1973, Barth, ISBN: 9783870412654

comments