Mental qualities emphasized in Zen practice

Zen places particular emphasis on the direct experience of reality through meditation and intuitive insight. While this school is often associated with paradox, spontaneity, and aesthetic simplicity, its foundation lies firmly within the core principles taught by Siddhartha Gautama. At its heart, Zen does not advocate a different doctrine, but rather a distinct approach to the realization of impermanence, interdependence, and non-self.

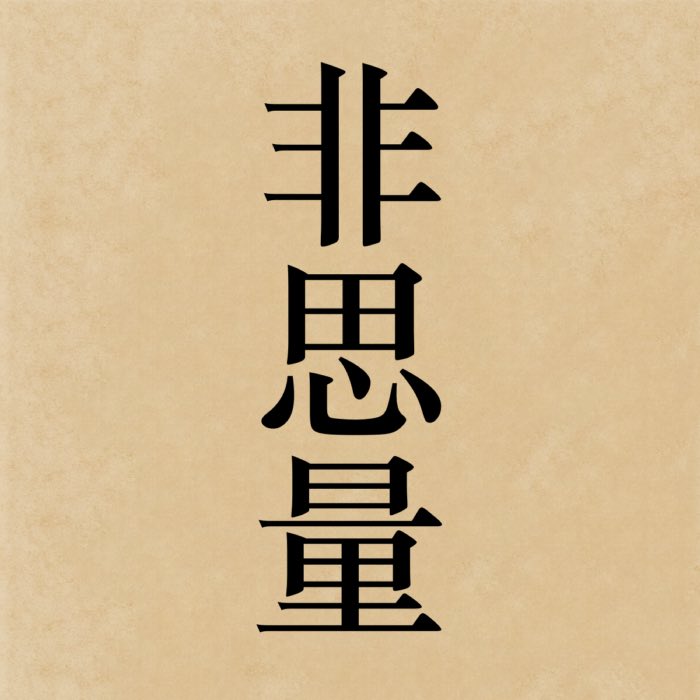

Zenga (Zen ink painting) evoking the mental qualities cultivated in Zen practice — serenity, focus, and non-attachment — symbolized by a lone figure amid a vast, layered mountain landscape. Interpreted by DALL•E 2.

A recurring theme in Zen training is the cultivation of specific states of mind. These are not to be seen as fixed stages or mystical attainments, but rather as dynamic dispositions — mental qualities that emerge from embodied practice and deepened insight. These states are closely tied to Siddhartha’s teachings, particularly the Eightfold Path, mindfulness (sati), the cultivation of mental qualities (citta-bhāvanā), and the renunciation of clinging (upādāna).

In this post, we explore the key mental states valued in Zen practice. While many originate from or are influenced by Japanese Zen, their psychological and philosophical underpinnings can be found throughout Buddhist thought. They reflect how the practitioner gradually transforms perception and engagement with reality.

Overview of key Zen mental states

The list below is ordered not by chronology or popularity, but by their depth of connection to Buddhist insight.

Foundational and essential realizations

Hishiryō (非思量) – Translated as “non-thinking”, this term refers to a mental state beyond both thinking and not-thinking. It is often invoked in the context of seated meditation (zazen), where it denotes a direct and non-dual mode of awareness. This concept does not advocate a blank mind, but rather a mode of consciousness that observes without conceptual interference. It echoes the early Buddhist emphasis on mindfulness (sati) and the cessation of discursive identification.

Datsuraku (脱落) – Literally meaning “dropping off body and mind”, this expression originates from the encounter between Dōgen and his Chinese teacher Rujing. It marks the shedding of all attachments to form, identity, and thought. In Buddhist terms, it reflects the insight into anattā (non-self) and the renunciation of craving. It is not merely symbolic, but descriptive of a transformation in how reality is experienced.

Mushin (無心) – Often translated as “no-mind”, mushin designates a state free of obstructive thoughts, intentions, or egoic impulses. It is not a negation of consciousness, but a purification of it: a return to direct responsiveness without fixation. The concept parallels the early Buddhist ideal of right mindfulness and the stilling of the five hindrances.

Samadhi / Zanmai (三昧) – A core term shared across all Buddhist traditions, samādhi refers to meditative absorption or collectedness of mind. In Zen, various forms of zanmai are spoken of, such as the self-fulfilling samādhi (jijuyū-zanmai), which embodies meditative awareness in all activities. This reflects a fully integrated form of right concentration (sammā samādhi).

Central meditative attitudes

Shoshin (初心) – Meaning “beginner’s mind”, this attitude values openness, curiosity, and the absence of preconceptions. It reflects a constant readiness to encounter each moment anew. This mental stance is aligned with the Buddhist idea of impermanence (anicca) and the insight that every moment arises freshly and cannot be reduced to past experience.

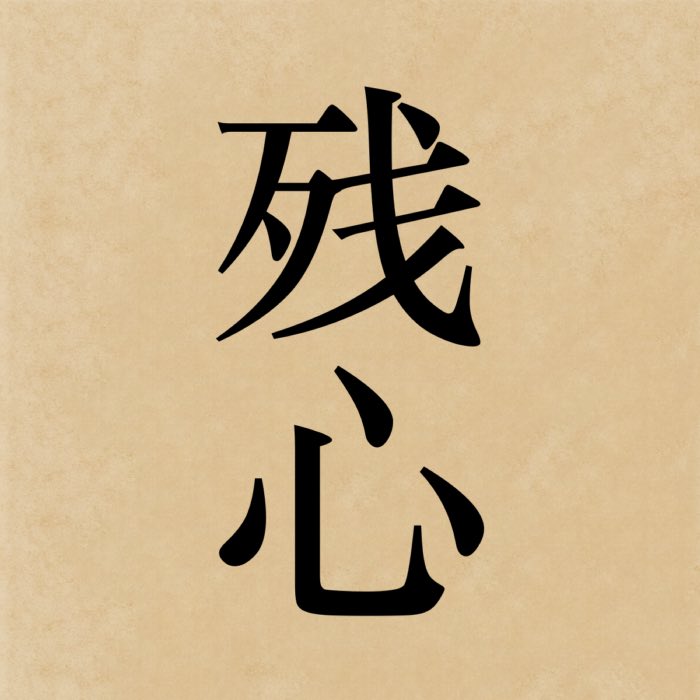

Zanshin (残心) – Literally “lingering mind” or “remaining mind”, zanshin denotes a state of sustained awareness that continues before, during, and after an action. It is especially cultivated in Zen arts and martial disciplines. Zanshin reflects the training of sati: a continuous presence that neither grasps nor ignores.

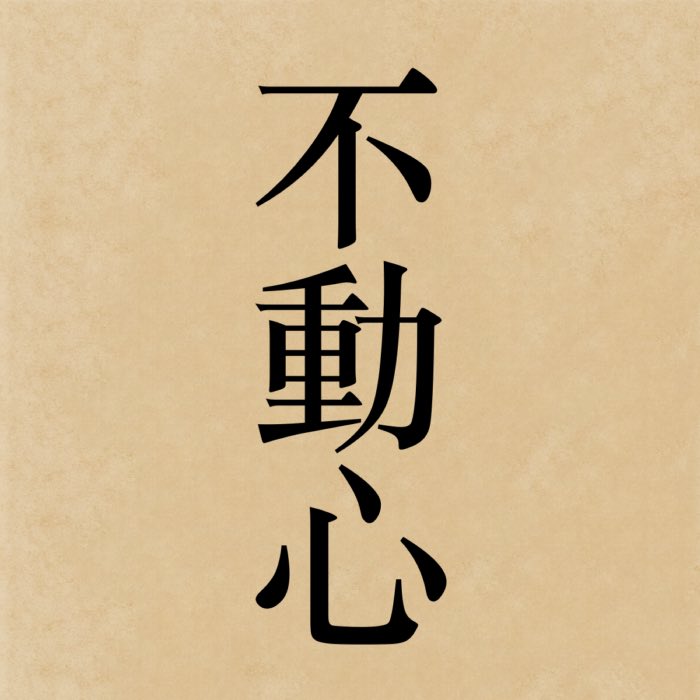

Fudōshin (不動心) – Translated as “immovable mind”, this state is characterized by equanimity and inner stability. Fudōshin does not imply rigidity but the ability to remain mentally unshaken amid circumstances. It is closely related to the Brahmavihāra of upekkhā (equanimity), and to the cultivation of balance on the Buddhist path.

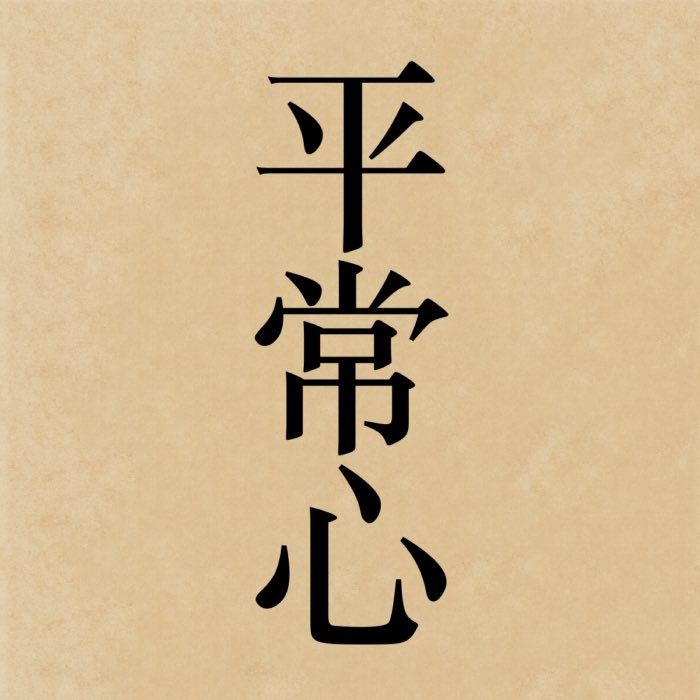

Heijōshin (平常心) – Often rendered as “everyday mind” or “calm mind”, this state describes the quality of serenity and presence in ordinary activities. It emphasizes that insight and peace are not limited to formal meditation but can permeate all of daily life. This attitude is congruent with the integration of meditation and ethics (sīla) found in early Buddhist practice.

Aspirational or supportive attitudes

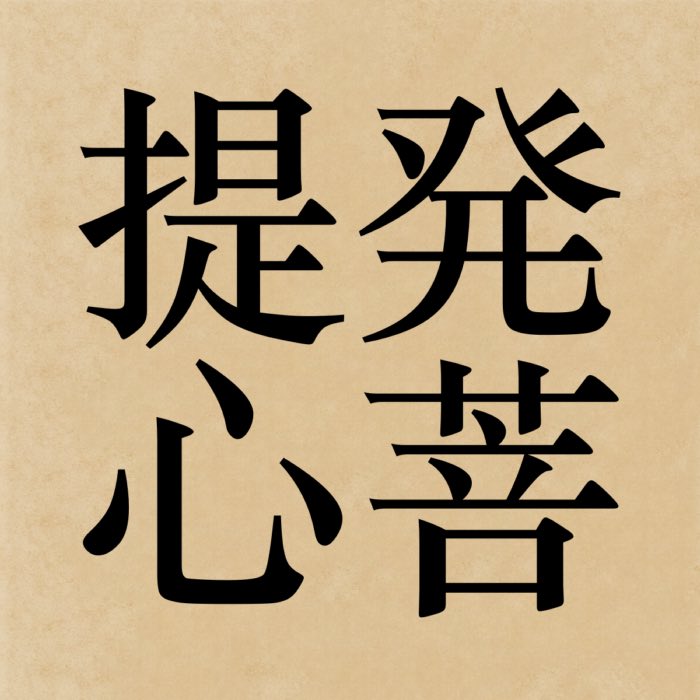

Hotsu bodaishin (発菩提心) – This Mahāyāna concept refers to the arising of the “bodhi mind” — the aspiration to attain awakening for the benefit of all beings. It is considered the starting point of the Bodhisattva path. While more doctrinally Mahāyāna, its spirit reflects the universalization of compassion found already in Siddhartha’s teachings.

Isshin (一心) – Meaning “one mind” or “wholeheartedness”, isshin refers to a state of unified attention and total sincerity. It captures the focused resolve needed for sustained practice. It shares characteristics with sammā vāyāma (right effort) and the unification of mind and body found in meditative absorption.

Shisei (姿勢) – Though it literally means “posture”, shisei refers not only to physical form but to the mental attitude expressed through bodily presence. Proper posture in Zen is not ornamental; it serves as a form of mindfulness in action. It reflects the embodied nature of Buddhist meditation.

Gaman (我慢) – Often translated as “enduring patience”, gaman emphasizes bearing hardship without complaint. Though the term also appears in secular Japanese culture, in Zen it denotes inner resilience. It recalls the pāramī of khanti (patience), one of the central virtues cultivated on the Buddhist path.

Kansha (感謝) – Meaning “gratitude”, kansha is not merely polite thankfulness, but a deep appreciation for all conditions of life, including suffering and impermanence. This state reflects a mature understanding of dependent origination and the transformative power of acceptance.

Mind–body integrated disciplines

Shinshin (心身) – Meaning “mind-body”, this term expresses the non-duality of mental and physical phenomena. It aligns with the Buddhist understanding that body and mind are not separate substances but interdependent processes. In Zen, this manifests through practices that unify posture, breath, and awareness.

Shingitai (心技体) – This compound term translates as “mind, technique, body.” It refers to the harmony of mental, technical, and physical elements in practice. While it originates in martial disciplines, it encapsulates the holistic nature of Zen training — where skill, attention, and embodiment are inseparable.

Mosshōseki (没蹤跡) – Mosshōseki means “leaving no trace behind” and expresses a key Zen principle: to act fully and responsively in the world without clinging to actions, outcomes, or a constructed self-image. Rooted in the Buddhist insights of impermanence (anicca), non-attachment (anupādā), and the perfection of wisdom (prajñāpāramitā), Mosshōseki describes a way of living where engagement is sincere yet free from self-centered residue. It reflects the realization of suchness (tathatā) in practice, allowing actions to emerge naturally from a mind unobstructed by grasping.

Cultivation and cautions

The cultivation of these states is not achieved by striving to possess them. In fact, one of the central tenets of Zen — mirroring Siddhartha Gautama’s core insight — is that clinging, even to mental states or virtues, leads to suffering. Each of these attitudes arises as a result of non-clinging observation, ethical conduct, and meditative training. They are not goals but byproducts of a life lived in attention and simplicity.

Zen warns repeatedly against attachment to spiritual states, recognizing that the desire to attain, even to attain non-attachment, is itself a subtle form of grasping. The ideal is not to fixate on these mental qualities, but to allow them to emerge naturally from consistent practice.

Rather than constructing a new identity around them, Zen encourages an emptying out — a return to what simply is.

Practical cultivation in tradition and lay life

Within the Zen tradition, these states of mind have been cultivated primarily through zazen (seated meditation), strict monastic routines, and the integration of mindfulness into every facet of daily life — from walking and working to eating and interpersonal interaction. Monastic training is designed not merely to instill discipline, but to remove distractions and bring habitual patterns of grasping into direct awareness. Silence, repetition, and simplicity serve to redirect attention from abstract speculation to immediate presence.

Moreover, these mental attitudes are not acquired as isolated experiences but are refined over years through kōan practice, ritualized behavior, and close contact with a teacher. In Rinzai Zen, for instance, the sharp encounter with a koan is meant to cut through habitual thinking and elicit a direct response that cannot be planned or reasoned through. In Sōtō Zen, the focus is more on uninterrupted sitting, where the very act of sitting becomes an expression of realization itself.

For lay practitioners, the path may look different, but the underlying principles remain. While most readers will not live in monasteries, the cultivation of these mental states can still occur within the conditions of daily life. Regular meditation, attentiveness to breath and posture, and a willingness to observe emotional reactivity in the moment offer accessible gateways. The key lies not in isolating practice from life, but in letting life itself become the ground of training.

A few general suggestions may serve as practical orientation:

Rather than attempting to master these states or adopt them as ideals, one might simply observe which of them arises naturally under what conditions. Instead of trying to “possess” a beginner’s mind or an immovable mind, one can notice how preconceptions arise and how reactivity ebbs and flows.

Practicing with sincerity rather than ambition helps prevent spiritual materialism — the subtle tendency to collect insights or attitudes as one might collect achievements. Clinging to even the most admirable state of mind becomes counterproductive when it reinforces the illusion of a permanent self. Zen tradition continually warns that even detachment can become a form of attachment if held too tightly.

Ultimately, the cultivation of these states is not a linear journey toward becoming a perfected person, but an ongoing reorientation toward what Siddhartha Gautama described as seeing things as they are, without distortion. These states of mind are less about acquisition than about the gentle undoing of habits that obscure clarity.

Conclusion

The discussed states of mind illustrate the Zen tradition’s unique approach to the cultivation of mental qualities. Rather than treating these as discrete stages or spiritual attainments, Zen frames them as modes of being that emerge through deep familiarity with impermanence, non-self, and the conditioned nature of reality. Whether foundational, like hishiryō and datsuraku, or supportive, like gaman and kansha, these states reflect the dynamic interplay between disciplined practice and experiential insight.

While their terminology and aesthetics are rooted in East Asian culture, the underlying principles remain consistent with the early teachings of Siddhartha Gautama. Core themes such as mindfulness, right concentration, equanimity, and ethical awareness run through both early Buddhism and Zen, though the latter emphasizes intuitive experience over analytic articulation. Compared to some Theravāda approaches, which often emphasize gradual progress and clear doctrinal analysis, Zen resists intellectual systematization. This can make its language appear elusive or paradoxical, yet the core goal remains the same: freedom from suffering through clarity and non-attachment.

In comparison to Western philosophical or psychological frameworks, Zen offers an alternative to the model of self-improvement based on control, productivity, or identity. Where Western traditions often emphasize agency and the cultivation of virtues as stable traits, Zen stresses non-grasping, unselfing, and responsiveness to conditions. This contrast can serve as a corrective to modern tendencies toward instrumentalizing the mind for specific outcomes, such as efficiency or self-optimization. In this respect, Zen’s refusal to turn mental states into goals may be one of its most critical contributions.

Yet, Zen does not reject discipline or effort; it reframes them. Practice is necessary — not to become someone else, but to undo what obstructs immediate presence. The states of mind described here are not prescriptions but descriptions: they name what tends to arise when one stops clinging. In this way, Zen preserves the psychological depth of early Buddhism while offering a method that is radically embedded in the present moment.

Ultimately, the value of these states lies not in possessing them but in allowing them to shape one’s mode of participation in life. They do not separate the spiritual from the everyday but reveal their inseparability. Zen thus reaffirms, in its own vocabulary, a fundamental Buddhist insight: that liberation does not lie in distant ideals, but in the unobstructed experience of what is already here.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments