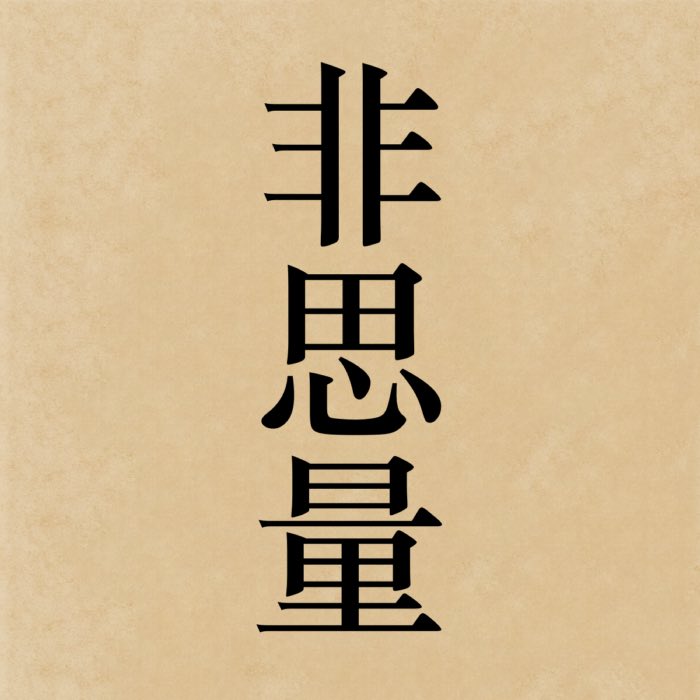

Hishiryō: The Zen concept of non-thinking

Among the various states of mind cultivated in Zen, hishiryō (非思量), often translated as “non-thinking”, holds a foundational position. It is closely associated with zazen, the seated meditation practice that forms the core of Zen training. Despite its seeming paradox, hishiryō does not advocate the cessation of all mental activity nor a forced blankness of mind. Instead, it designates a mode of awareness that transcends both conceptual thinking and the deliberate effort to suppress thought. In this respect, it echoes and deepens the early Buddhist emphasis on mindfulness (sati) and the cessation of discursive attachment.

The kanji 非思量, which reads hishiryō in Japanese, literally means “non-thinking” or “non-conceptualization”. The first character, hi (非), indicates negation or non-existence. The second character, shi (思), means “to think” or “to consider”. The third character, ryō (量), refers to measurement or quantification. Together, they convey the idea of a state of mind that transcends ordinary thinking and conceptualization.

Meaning and background

The term hishiryō can be broken down into three components: “hi” (non-, negation), “shi” (thinking), and “ryō” (to measure, to consider). Thus, hishiryō points to a state that goes beyond measuring, judging, or calculating. It was notably emphasized by Dōgen (1200–1253), a key figure in Japanese Sōtō Zen, who used the term to describe the state of mind appropriate to true meditation.

In Dōgen’s instructions, hishiryō is not a passive state but an active engagement with reality without falling into the usual traps of conceptual categorization. It does not mean stopping thought through force, nor does it mean becoming absorbed in a trance-like state. Rather, it reflects an awareness that allows phenomena — thoughts, sounds, sensations — to arise and pass without interference or grasping. Thought may arise, but the mind does not attach itself to thoughts, pursue them, or construct identities around them. There is a clear knowing, yet it does not solidify into judgments or reflexive positions such as “I am thinking” or “I am not thinking”. Instead, this knowing is immediate, fluid, and unburdened by commentary.

This conception aligns closely with Siddhartha Gautama’s teachings on right mindfulness and right concentration. In early Buddhist discourse, the goal was not to stop mental phenomena altogether but to observe them without attachment, allowing craving and aversion to fall away. Hishiryō represents a Zen refinement of this orientation: awareness so immediate and ungrasping that the distinction between observer and observed dissolves.

Practical aspects

In practice, hishiryō is cultivated most directly through shikantaza (“just sitting”), a form of meditation without objects, anchors, or goals. Unlike focused attention practices that center on the breath or a mantra, shikantaza involves resting in awareness itself. Thoughts may come and go, but they are not engaged with. Sensations arise, but they are not pursued or rejected.

The challenge for practitioners is that the tendency to fall into either discursive thinking (shiryō) or suppression of thought (fushiryō) is strong. Hishiryō stands precisely in the middle: neither indulging in thoughts nor trying to eliminate them. Dōgen described this as “thinking non-thinking”, an expression meant to direct the practitioner beyond habitual mental habits without creating a new object of fixation.

Zen masters often caution against trying to “achieve” hishiryō. Attempting to force non-thinking simply introduces another layer of conceptualization. Instead, it is through sincere and sustained practice that the mind naturally settles into a state where thoughts lose their stickiness, and awareness becomes unobstructed.

Philosophical relevance and comparison

From a philosophical standpoint, hishiryō challenges conventional notions of cognition and agency. In contrast to Western traditions that often equate human dignity with rational thinking, Zen’s concept of non-thinking suggests that the deepest form of understanding arises when the compulsive need to categorize reality is set aside. This does not devalue reason but places it within a larger context where immediate experience is primary.

Comparing this to other Buddhist schools, one finds similar ideas in early Buddhist practices of mindfulness and non-clinging, though often expressed in more systematic and analytic terms. In Mahāyāna traditions such as Yogācāra, one also encounters the notion of “non-conceptual wisdom” (nirvikalpa-jñāna), pointing toward a direct awareness beyond conceptual thought. Zen’s contribution is its radical simplicity: it neither elaborates complex doctrinal systems nor posits higher states to be reached. Instead, it insists that ‘suchness’ is immediately available when thinking ceases to dominate experience.

Conclusion

Hishiryō captures a fundamental contribution of Zen thought to the broader Buddhist tradition: the recognition that liberation does not depend on acquiring superior forms of thinking, but on stepping outside of thought’s compulsive structures altogether. By neither clinging to nor suppressing thought, the practitioner cultivates a form of presence that is neither reflexively interpretive nor conceptually fixed. This orientation distinguishes Zen from more analytic schools of Buddhism as well as from philosophical traditions that prioritize cognition as the highest human faculty. In hishiryō, the emphasis falls on awareness as such — an immediacy that neither requires intellectual formulation nor aims to transcend experience. In this sense, hishiryō aligns with the original intent of Siddhartha Gautama’s path: to develop clarity, equanimity, and freedom through non-clinging engagement with the unfolding flow of life.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments