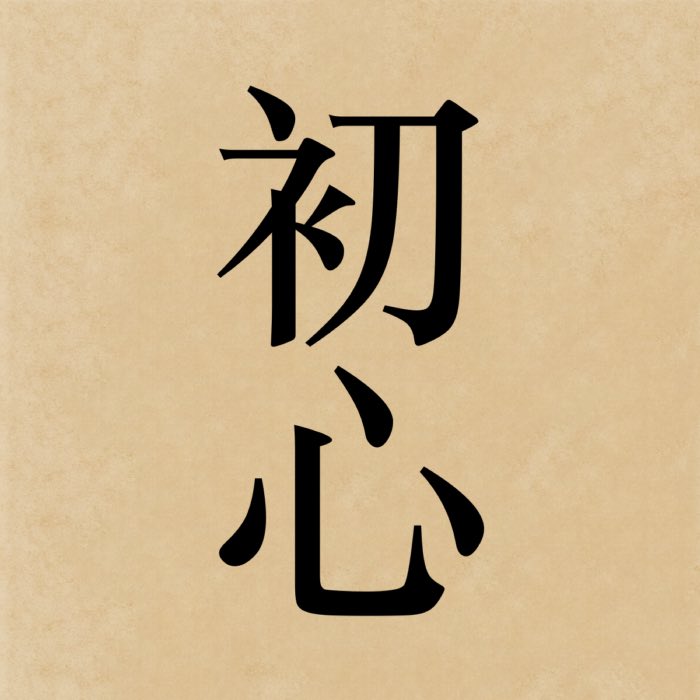

Shoshin: The beginner’s mind in Zen

Among the many attitudes cultivated in Zen, few are as well-known or widely applicable as shoshin (初心), often translated as “beginner’s mind”. The term refers to an attitude of openness, curiosity, and non-attachment to preconceived ideas. Although the phrase has found popular usage well beyond its Zen context, its origin and significance lie in the Zen tradition’s emphasis on direct experience and the continuous unfolding of practice. Far from being a naïve or passive stance, shoshin is a disciplined receptivity — a state of mind that remains unfixed even in the presence of knowledge or expertise.

The kanji 初心, which reads shoshin in Japanese, literally means “beginner’s mind”. The first character, 初 (sho), means “beginning” or “initial”. The second character, 心 (shin), means “mind” or “heart-mind”. Together, they convey the idea of a fresh and open state of mind that is free from preconceived notions and attachments.

Etymology and historical background

The Japanese term shoshin combines 初 (sho), meaning “beginning” or “initial”, with 心 (shin), meaning “mind” or “heart-mind”. In classical Chinese and Japanese Buddhism, shoshin referred to the mind one has at the outset of practice — a mind free from attachment to outcome and unburdened by conceptual complexity.

The modern Zen usage, however, owes much to the 20th-century Sōtō Zen teacher Shunryū Suzuki, who popularized the term in the West. In his book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Suzuki wrote: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind there are few”. This statement captures a core Zen intuition: that conceptual certainty and spiritual progress can become forms of subtle attachment, narrowing one’s openness to reality as it is.

Shoshin in Zen practice

In the context of zazen and everyday training, shoshin is not confined to the novice phase but is cultivated continuously. It refers to the quality of mind that approaches each moment freshly, without imposing habitual interpretations. Even long-term practitioners are encouraged to sit each time as if for the first time, without comparing the current moment to past experiences or future expectations.

This attitude is particularly important in Zen, where experience is prioritized over doctrine and spontaneity over fixed form. In formal settings, such as bowing, chanting, or cooking, the practitioner is encouraged to approach tasks with full attention, regardless of repetition. The point is not to perfect the form but to meet it without preconception.

Shoshin also applies to the internal life of the practitioner. When thoughts or emotions arise, the beginner’s mind receives them without labeling or resistance. Rather than classifying an emotion as positive or negative, useful or disruptive, one simply notices its arising and passing. This supports the Buddhist aim of non-reactivity and insight into impermanence (anicca).

Comparison and relevance in Buddhist context

The concept of shoshin resonates with early Buddhist teachings on right mindfulness (sammā sati), which instructs the practitioner to observe experience as it is, without judgment or clinging. The Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, for instance, emphasizes direct observation of bodily sensations, feelings, and mental states with sustained attention and without conceptual overlay. Shoshin echoes this orientation, but with a tone of deliberate humility and renewal.

In Mahāyāna traditions, shoshin parallels the Bodhisattva ideal of maintaining an open heart and a flexible mind in the face of endless learning. The idea is not to graduate from beginner’s mind but to deepen it — to remain fully responsive, even as understanding grows. Dōgen himself, despite his philosophical depth, consistently returned to the call for sincerity and unpretentiousness in practice.

Philosophical implications and comparison with Western thought

From a philosophical standpoint, shoshin challenges the common assumption that wisdom is primarily the accumulation of knowledge. In many Western traditions, especially in modernity, mastery is associated with specialization and certainty. By contrast, shoshin suggests that insight often arises from a conscious unknowing — a suspension of fixed frameworks that allows reality to disclose itself anew.

This aligns with Zen’s broader skepticism toward conceptual elaboration. Where other traditions may value correct answers, Zen often values the quality of the questioning mind. In this sense, shoshin is not a regression to ignorance but an intentional stance that refuses to solidify experience into conclusions.

Conclusion

Shoshin highlights a defining feature of Zen practice: the refusal to treat spiritual development as a linear accumulation of insight. Instead, it emphasizes sustained openness and the willingness to meet each moment without the filter of prior conclusions. This approach offers a counterpoint to traditions, both Eastern and Western, that equate wisdom with mastery or finality. Zen reinterprets maturity as the capacity to remain fresh, responsive, and free from fixed views. In this way, shoshin affirms a core Buddhist principle: that awakening is not the result of arriving somewhere new, but of fully inhabiting each moment as it is.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Werner Lind, Budō – Der geistige Weg der Kampfkünste, 2007, Nikol, Gebundene Ausgabe, ISBN-10: 393787254X

- Werner Lind, Lexikon der Kampfkünste, 2001, Penguin, ISBN-13: 978-3328008989

comments