Daisetz Suzuki: Spreading Zen to the West and refreshing its spirit

Among the pivotal figures who shaped the modern understanding of Zen Buddhism, few stand as prominently as Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki (1870–1966). Through his translations, lectures, and writings, Suzuki introduced Zen to a broad Western audience at a time when Eastern thought was little known outside Asia. His portrayal of Zen emphasized direct experience, psychological depth, and existential insight, making it accessible to scholars, artists, and spiritual seekers worldwide. In doing so, Suzuki not only transformed Western perceptions of Zen but also revitalized its spirit within Japan.

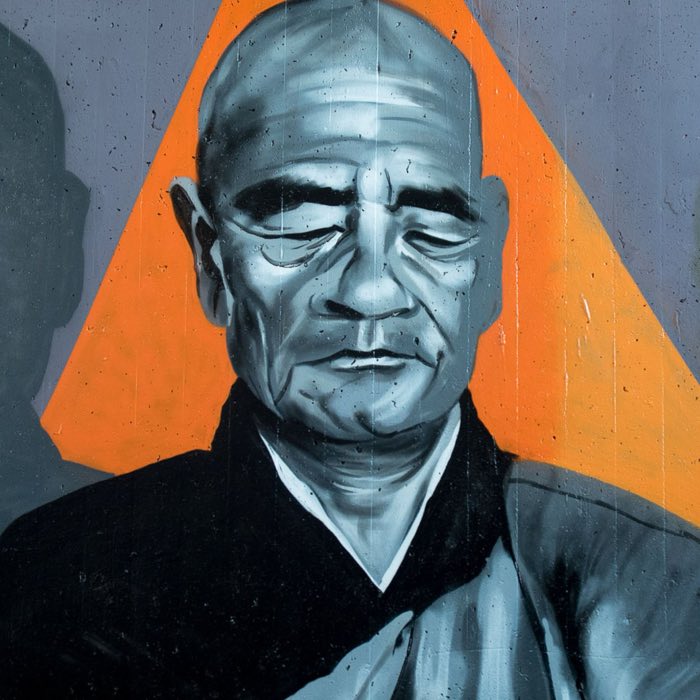

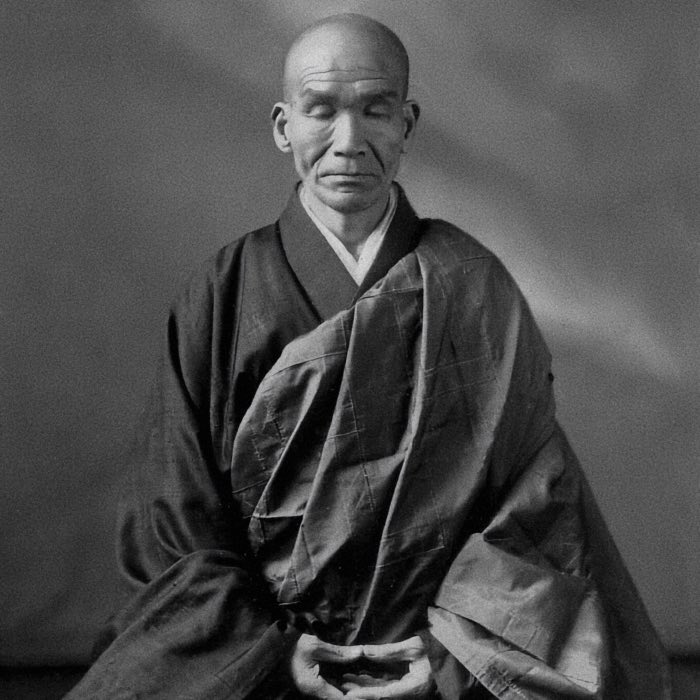

Daisetz Teitarō Suzuki (1870-1966), 1953. Daisetz was a Japanese author and philosopher known for his works on Zen Buddhism and its introduction to the West. He played a crucial role in popularizing Zen philosophy and practice outside Japan, particularly in the United States and Europe. His writings emphasized the experiential aspects of Zen, making it accessible to a broader audience. Suzuki’s influence extended to various fields, including psychology, art, and literature, where he inspired many thinkers and artists to explore Zen principles. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Biography

Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki was born in 1870 in Kanazawa, Japan, into a samurai family during the final years of the Meiji Restoration. His early life was marked by hardship: his father died when Suzuki was six, and his mother passed away when he was nineteen. Economic difficulties forced him to leave school at seventeen and earn a living by teaching English.

Supported by a brother, Suzuki moved to Tokyo, where he studied Western languages and literature at Waseda University and philosophy at the Imperial University. His friend Nishida Kitarō, later a major figure in Japanese philosophy, encouraged his academic pursuits.

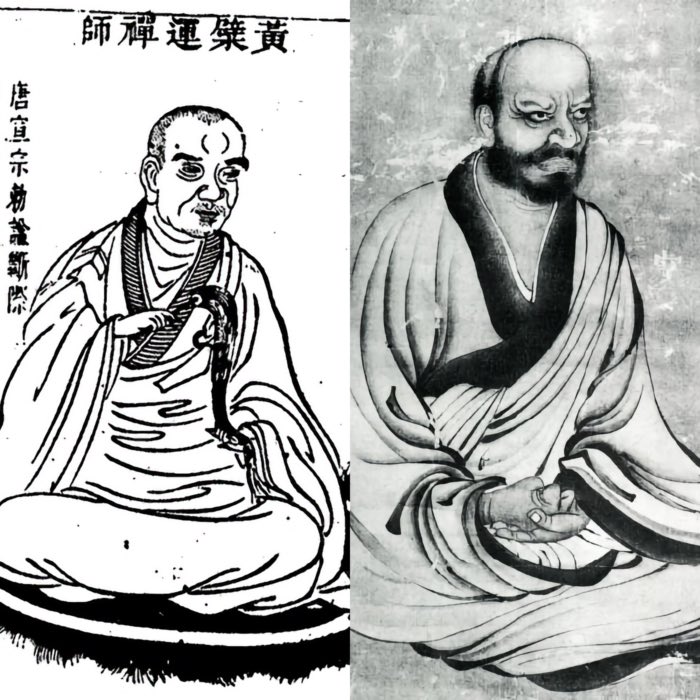

Suzuki’s spiritual journey deepened during this period of social upheaval, as Japan transitioned from feudal structures to modern institutions. Initially turned away from his family’s Rinzai Zen temple, Suzuki found a teacher in Imakita Kōsen at Engaku-ji in Kamakura. There he received his first kōan. After Kōsen’s death, Suzuki continued his training under Shaku Sōen, a forward-looking abbot who advocated adapting Zen to modernity and fostering dialogue among Buddhist traditions.

Suzuki’s linguistic talents made him an ideal assistant for Shaku Sōen, especially during the 1893 World Parliament of Religions in Chicago. There, Suzuki met Paul Carus, a prominent Western publisher of Buddhist texts. Remaining a novice, Suzuki experienced kenshō after solving the famous “sound of one hand clapping” kōan. His teacher awarded him the Buddhist name “Daisetsu” (“Great Simplicity”).

After completing his training in 1897, Suzuki moved to the United States to work with Carus on translations and publications. Over the next decade, he engaged in extensive translation, lecturing, and teaching work. In 1908, after a period in Europe, he returned to Japan.

In Japan, Suzuki taught English and remained close to his Zen roots near Engaku-ji. In 1911, he married Beatrice Erskine Lane, an American theosophist. Together they founded the Tokyo International Lodge of the Theosophical Society in 1920 and later the Mahayana Lodge in Kyoto. In 1921, with encouragement from Nishida, Suzuki became a professor at Ōtani University in Kyoto, specializing in Buddhist philosophy. That same year, he and Beatrice founded the Eastern Buddhist Society and began publishing “The Eastern Buddhist,” an English-language journal focused on Mahāyāna Buddhism.

Suzuki spent the 1930s lecturing across Europe and the United States. After World War II, he returned to America, teaching at Columbia University from 1952 to 1957. He continued to shape the understanding of Zen for new audiences. Honored with the Japanese Order of Culture (1949) and the Asahi Prize (1954), Suzuki passed away in 1966 in Tokyo, leaving an enduring legacy.

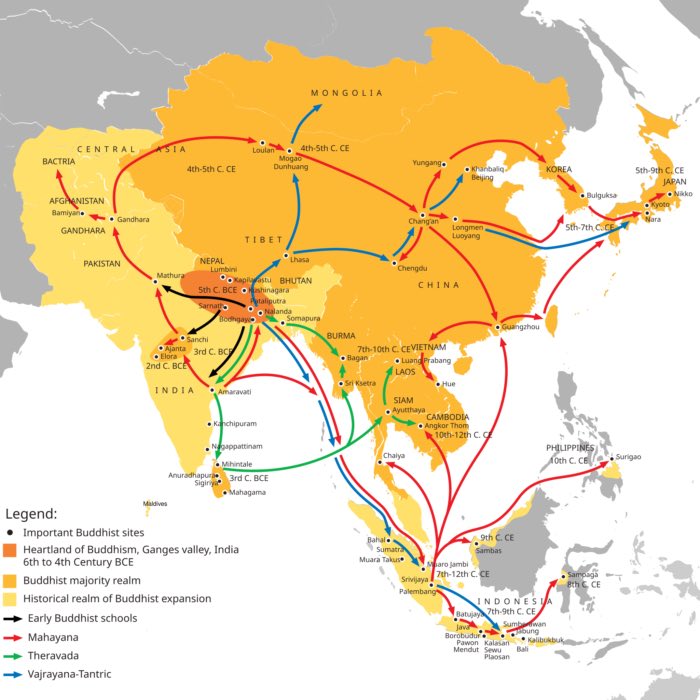

Spreading Zen to the West

Suzuki’s influence in the West cannot be overstated. Through works such as “Essays in Zen Buddhism” (1927) and “An Introduction to Zen Buddhism” (1934), he presented Zen not as a scholastic or ritualistic tradition, but as a path to direct, experiential insight beyond conceptual thought.

His clear, accessible prose framed Zen in existential and psychological terms, resonating with contemporary Western intellectual currents. By emphasizing satori (awakening), spontaneity, and non-dual awareness, Suzuki captured the imagination of philosophers, psychologists, artists, and writers. Figures such as Carl Jung, Erich Fromm, Thomas Merton, and later the Beat poets were deeply influenced by his work.

Suzuki’s lectures and writings helped establish Zen as a major force in twentieth-century Western thought, connecting it with emerging interests in psychology, existentialism, and modern art. His ability to communicate profound Buddhist concepts in terms relatable to Western audiences marked a watershed moment in global intellectual history.

Refreshing Zen in Japan

While Suzuki is often celebrated for his role in bringing Zen to the West, his influence within Japan was equally significant. In presenting Zen as a living, dynamic tradition centered on direct experience, he challenged the increasingly formalistic and scholastic tendencies that had taken hold in many Japanese Zen institutions.

Suzuki’s work encouraged a return to the core spirit of Zen: the pursuit of awakening through direct, personal experience. By highlighting satori as the heart of Zen practice, and by framing Zen as a universal, existential endeavor rather than an insular monastic discipline, Suzuki revitalized interest among both laypeople and clergy.

Moreover, by engaging with modern philosophy, psychology, and comparative religion, Suzuki demonstrated that Zen could evolve and remain relevant in a rapidly changing world without losing its essential character.

Critiques and legacy

Despite his enormous contributions, Suzuki’s interpretations have not been without criticism. Some scholars argue that he idealized and romanticized Zen, portraying it as purely spontaneous and intuitive while downplaying the rigorous discipline and ethical frameworks integral to traditional practice.

Others have noted that Suzuki’s presentation of Zen was influenced by Western philosophical categories, such as existentialism and Romanticism, subtly reshaping Zen to fit modern Western tastes. Critics also point out that he sometimes neglected the sociopolitical contexts of Zen’s historical development, presenting a de-historicized, universalist vision.

Nonetheless, Suzuki’s impact is undeniable. He succeeded in opening Zen to a global audience, inspiring generations of practitioners, scholars, and artists. Without his pioneering efforts, the profound resonance of Zen in global modern and contemporary culture would likely have been much weaker.

Conclusion

Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki stands as a pivotal figure in the transmission and transformation of Zen Buddhism in the modern era. His life’s work built bridges between East and West, between tradition and modernity. Through clear exposition and deep insight, he made Zen accessible without trivializing its profound demands.

Critically, Suzuki’s interpretation of Zen not only introduced Western audiences to key concepts like satori, non-duality, and direct experience but also helped renew the spirit of Zen practice in Japan itself. Even as debates about his portrayals continue, his influence remains foundational.

Suzuki showed that Zen was not merely a relic of a monastic past but a living tradition capable of speaking to the modern human condition. In this way, he did not merely export Zen, he helped refresh its meaning for a new world.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

Suzuki’s most important works:

- Essays in Zen Buddhism,

- First Series. Rider, London 1970

- Second Series. Rider, London 1970

- Third Series. Rider, London 1970;

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Zen und die Kultur Japans, 1970, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki (Autor), C. G. Jung (Einleitung), Felix Schottlaender (Übersetzer), Die große Befreiung. Einführung in den Zen-Buddhismus, 2003, Otto Wilhelm Barth, 20. Auflage, ISBN-10; 3502675945

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Leben aus Zen, Eine Einführung in den Zen-Buddhismus, 1987, Otto Wilhelm Barth

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Satori, Der Zen-Weg zur Befreiung. Die Erleuchtungserfahrung im Buddhismus und im Zen, Otto Wilhelm Barth (1. Januar 1996), ISBN-10: 3502645949

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki (Autor), Jochen Eggert (Übersetzer), Zazen: Die Übung des Zen: Grundlagen und Methoden der Meditationspraxis im Zen, 1. Januar 1990, Herausgeber: O. W. Barth; 2. Edition, ISBN-10: 3502645957

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Der Sprung ins Grenzenlose, Das Koan als Mittel der meditativen Schulung im Zen, 1994, 2. Auflage, Otto Wilhelm Barth Verlag

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Karuna, Zen und der Weg der tätigen Liebe, Der Bodhisattva-Pfad im Buddhismus und im Zen, 1. Januar 1996

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Prajna, Zen und die Höchste Weisheit, Die Verwirklichung der „transzendenten Weisheit“ im Buddhismus und im Zen, 1. Januar 1990, O. W. Barth, ISBN-10: 3502645981

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Shunyata, Die Fülle in der Leere, Essays über den Geist des Zen in Kunst, Kultur und Religion Japans, 1991, Otto Wilhelm Barth

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Mushin, Die Zen-Lehre vom Nicht-Bewusstsein, Das Wesen des Zen nach den Worten des Sechsten Patriarchen, 1. Januar 1996

- Daisetz T. Suzuki, Der westliche und der östliche Weg, 1957 (Originalausgabe auf Englisch) bzw. 1974 (deutsche Ausgabe), Ullstein Taschenbuch Verlag, aus der Reihe Weltperspektiven. (Nr.299), ISBN-10: 3548022995

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Ur-Erfahrung und Ur-Wissen - die Quintessenz des Buddhismus, 1983, Octopus-Verlag, ISBN: 9783900290245

comments