Siddhartha Gautama: The historical person behind the Buddha myth

Who was Siddhartha Gautama before he became the Buddha, the most central figure in Buddhism? In this post, we explore that question from a historical perspective, seeking to reconstruct a plausible biography of the man behind the myth. While centuries of devotion and tradition have elevated him into a symbol of awakened wisdom, Siddhartha’s actual life likely began in a small tribal republic in northern India during the 5th or 6th century BCE.

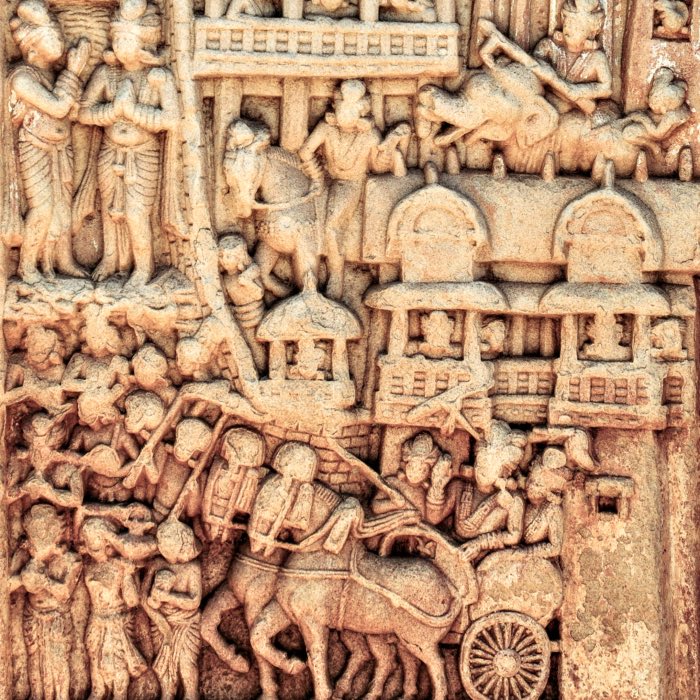

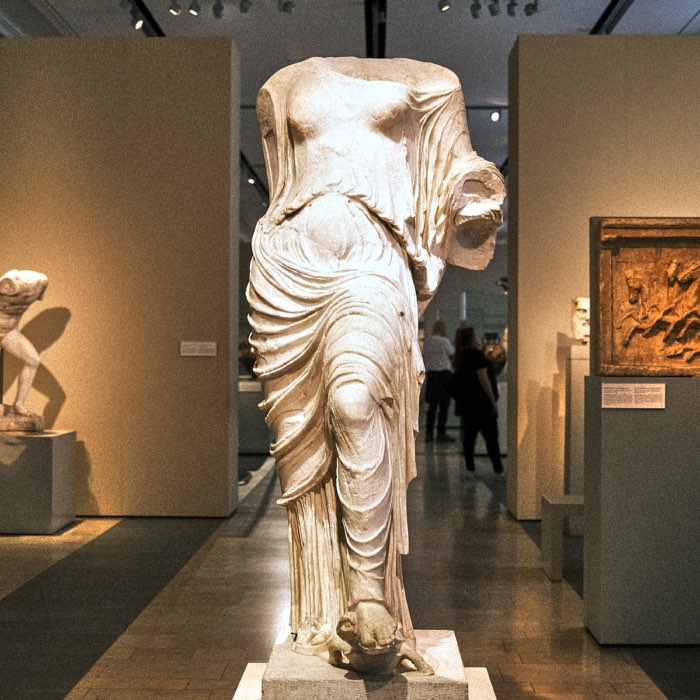

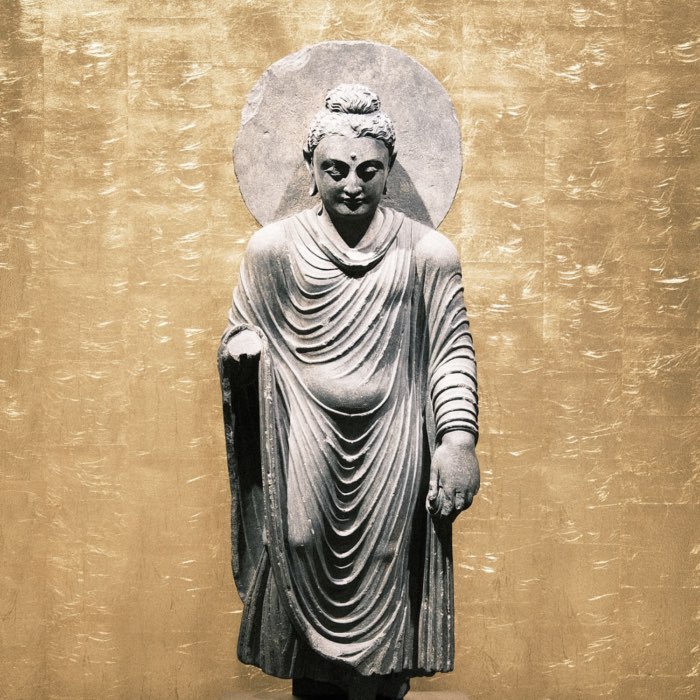

Standing Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara, Takht-i-Bahi, 2nd -3rd c., schist. In this post, we are going to reveal the historical person behind the Buddha myth. Exhibited at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, 2023.

Standing Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara, Takht-i-Bahi, 2nd -3rd c., schist. In this post, we are going to reveal the historical person behind the Buddha myth. Exhibited at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, 2023.

Rather than dismissing the textual and oral traditions that preserve his memory, this article reads them critically — neither accepting supernatural claims at face value nor ignoring the consistent patterns that suggest a coherent human story. It situates Siddhartha in the vibrant social, political, and intellectual landscape of his time, and follows his transformation from a privileged heir to a seeker, teacher, and founder of one of the most enduring philosophical traditions in human history.

Our goal is not to strip away meaning from the Buddha figure, but to understand the historical Siddhartha Gautama: a thinker shaped by his world, whose radical reimagining of spiritual life continues to resonate today.

Historicity of Siddhartha Gautama

The question of Siddhartha Gautama’s historicity is not whether he existed or not in a strict empirical sense, but how we can reconstruct a plausible life story from the limited and layered sources we have. Unlike modern biographies, historical reconstructions of ancient spiritual figures must rely on late, indirect, and often mythologized accounts. Still, a surprisingly consistent and coherent picture of Siddhartha emerges from these records — especially when read critically.

Sources: Archaeological, scriptural, and third-hand references

We can roughly divide our sources into three categories:

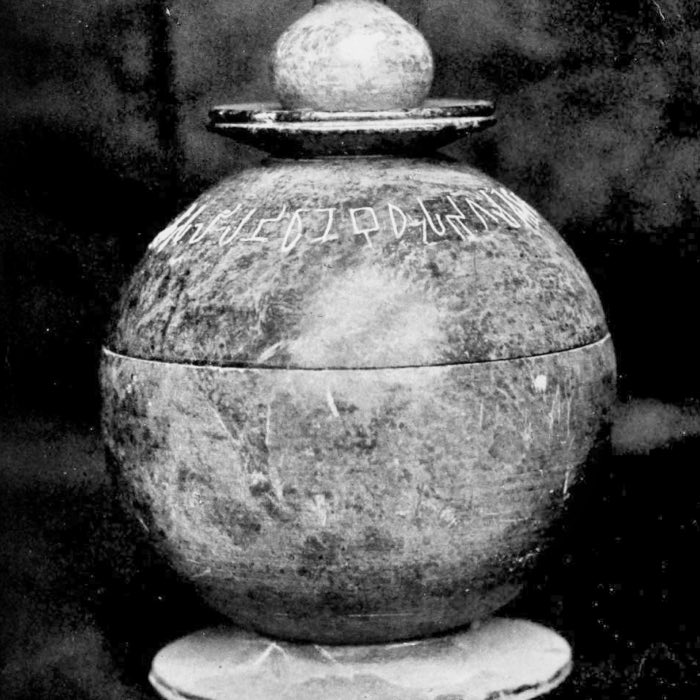

1. Archaeological evidence: Physical sites such as Lumbini (his traditional birthplace), Bodh Gaya (the place of awakening), Sarnath (where he is said to have given his first discourse), and Kushinagar (where he is believed to have died) lend credibility to the geographic and cultural outline of his life. These sites, with inscriptions and relics dating to a few centuries after his death, support the broader narrative even if they cannot confirm personal details.

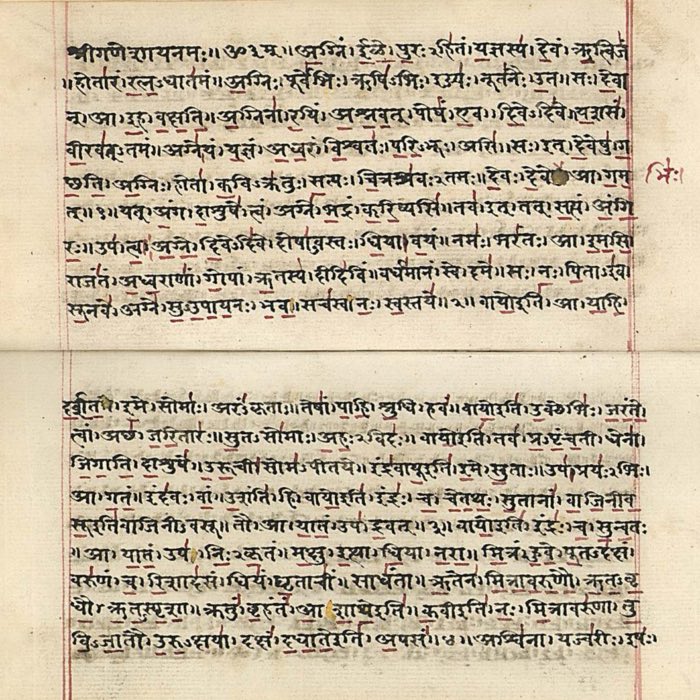

2. “Direct” scriptural sources: No writings by Siddhartha himself survive, and the earliest Buddhist texts were compiled and transmitted orally for centuries before being written down. The Pāli Canon (Tipiṭaka) and other early collections such as the Āgamas in Chinese offer rich depictions of his teachings, dialogues, and biographical details. While these texts certainly contain layers of myth-making, they also reflect a consistent philosophical voice and a coherent narrative framework. Their internal consistency across different traditions (Theravāda, Mahāsāṃghika, Sarvāstivāda) lends some historical weight to the core biographical outline.

3. Third-hand scriptural sources: Later texts — such as biographies written in Sanskrit, Chinese, and Tibetan traditions — tend to embellish and deify Siddhartha, turning him into a supernatural figure. Nevertheless, they sometimes preserve echoes of older traditions and help trace the development of the Buddha image over time. There are also references to Siddhartha in non-Buddhist texts (e.g., Jain or Brahmanical sources), which help situate him in the broader intellectual climate of the time.

Oral tradition and the plausibility of a historical core

India’s rich oral culture means that teachings and biographical elements could be memorized, performed, and preserved with considerable fidelity across generations. The existence of fixed formulaic expressions, structured dialogues, and repeated sermon forms in the early texts suggests they were crafted to aid memorization. This strengthens the possibility that some aspects of Siddhartha’s life and words were preserved accurately enough to reconstruct a historical core.

A comparative note: Siddhartha and Jesus

The historicity of Siddhartha compares favorably with that of other ancient spiritual figures. Unlike Jesus — whose existence is debated in light of theories like Richard Carrier’s, which argue that Jesus began as a mythical celestial being later historicized — Siddhartha was always portrayed as a human teacher who lived and taught in a known historical setting. While both figures were subject to mythologization, Siddhartha’s portrayal in the earliest sources is more grounded and rational, embedded in a recognizable socio-political context rather than cosmic narrative alone.

In conclusion, although the historical Siddhartha is partially obscured by legend, the convergence of archaeological, oral, and textual evidence makes it plausible to speak of him as a real person. His teachings, community-building efforts, and biographical milestones reflect a consistent human story beneath the later layers of deification.

Historical-political landscape into which Siddhartha is born

Siddhartha Gautama was born into a dynamic period of transformation in the Indian subcontinent, traditionally placed around the 5th to 6th century BCE. This era, often referred to as the Second Urbanization, was marked by the re-emergence of city life, intensified agricultural production, expanded trade networks, and significant socio-political complexity.

Politically, the region was dominated by the Mahājanapadas, sixteen major kingdoms and republics that vied for influence. These ranged from powerful monarchies like Magadha and Kosala to smaller republics and oligarchic clans, such as the Śākya tribe into which Siddhartha was born. The Śākyas were organized as a gaṇa-saṅgha, a kind of oligarchic republic where decisions were made by council rather than hereditary monarchy. This environment may have contributed to Siddhartha’s later teachings on dialogue, non-dogmatism, and communal decision-making within the monastic order.

Simultaneously, the religious landscape was undergoing profound change. The dominance of Vedic Brahmanism — with its elaborate rituals, social stratification, and priestly authority — was being challenged by the rise of renunciate and non-theistic movements collectively known as the śramaṇa traditions. These included Jainism, Ājīvika, materialist schools like the Lokāyatas, and numerous other groups questioning the authority of the Vedas and seeking direct liberation through self-discipline, meditation, and insight.

It was within this fertile and contentious intellectual climate that Siddhartha began his spiritual quest. The śramaṇa movement provided both the framework and the counterpoints against which he would develop his own path — rejecting both the extremes of ritualism and radical asceticism, and proposing a Middle Way that integrated practical ethics, meditative discipline, and insight into human suffering.

Thus, Siddhartha’s life and teaching cannot be divorced from the social ferment and political diversity of his time. Rather than appearing as an isolated sage, he emerges as a thinker rooted in — and responding to — a broader movement of spiritual and social reform sweeping through northern India.

The Shakya clan

Siddhartha Gautama was born into the Śākya clan, a small but socially significant tribal republic located at the edge of the Gangetic plain, near what is today the Indo-Nepalese border. The Śākyas were organized as a gaṇa-saṅgha — a kind of aristocratic oligarchy where power was not centralized in a king but distributed among a council of elders or nobles. This political system valued deliberation, debate, and consensus, in contrast to the hereditary monarchies of neighboring regions.

Such a political environment likely shaped the young Siddhartha’s exposure to public discourse and collective governance. While his father, Suddhodana, is often described in later sources as a “king,” it is more accurate to see him as a prominent figure within the ruling council of the clan — possibly a chief among equals or a rotating head of state. This context adds nuance to Siddhartha’s later preference for dialogical teaching, egalitarian structures, and rules decided by the sangha rather than dictated from above.

It is plausible that the young Siddhartha attended public assemblies or court deliberations, listening to his father and other elders engage in persuasive speech and political reasoning. Such early experiences may have profoundly influenced his later skill in discourse and his ability to communicate complex philosophical insights through dialogue, parables, and structured debate. These qualities became hallmarks of his teaching style and the communal, rule-based structure of the early monastic community.

Birth and childhood

Scholars generally estimate Siddhartha Gautama’s birth to have occurred between 480 and 400 BCE, though traditional sources sometimes place it earlier. The dating remains debated due to the lack of contemporary records, but many historians align with the Theravāda tradition, which places his birth around 480 BCE and his death around 400 BCE. These approximations are based on backward calculations from the reign of Emperor Aśoka, who lived about a century later and played a major role in spreading Buddhism.

The birth of Siddhartha Gautama is surrounded by miraculous elements — such as his mother Queen Māyā dreaming of a white elephant entering her womb, or the newborn walking immediately after birth and declaring his destiny. These motifs are common in the birth narratives of great religious figures and are best understood as symbolic storytelling devices intended to convey the exceptional nature of the individual, rather than literal historical facts.

More historically grounded is the belief within the Śākya clan that Siddhartha was destined for greatness. According to early tradition, he was prophesied to become either a world-conquering monarch (cakravartin) or a fully enlightened spiritual teacher (Buddha). This prophecy may have shaped the way his upbringing was managed. While the image of a boy locked in a palace is likely an exaggeration, it reflects a plausible protective upbringing intended to shield him from spiritual inclinations and guide him toward a worldly, political future suitable for his noble status.

It is conceivable that Siddhartha grew up in relative luxury, within the confines of a ruling family concerned with lineage and tradition. This early life of privilege and insulation may help explain the intensity of his existential crisis when he finally encountered suffering and impermanence in the world outside. Rather than seeing his seclusion as imprisonment, we can understand it as the careful grooming of a potential clan leader — an intention he would later radically abandon in search of liberation.

His marriage and child

In accordance with his status as a noble son of the Śākya clan, Siddhartha Gautama was married at a young age to Yaśodharā, a woman from a similarly prominent family. This marriage was arranged to solidify social and political ties, and to further groom Siddhartha for a future role as clan leader. Together, they had a son named Rāhula, whose name — meaning “fetter” — was later interpreted symbolically in the early texts as reflecting Siddhartha’s growing sense of entrapment in worldly life.

While the early sources describe Siddhartha as enjoying the pleasures of palace life, they also hint at rising internal tensions. Despite fulfilling his role as husband and father, he began to experience profound existential doubt. His luxurious environment increasingly felt like a gilded cage rather than a source of happiness or purpose. The birth of his son — traditionally seen as a joyful event — may have intensified these doubts by anchoring him further to worldly responsibilities and attachments.

The psychological unrest that grew during this time set the stage for Siddhartha’s eventual renunciation. He began to question the meaning of life, the inevitability of aging and death, and the emptiness of status and pleasure. These inner conflicts would later crystallize into the teachings he would formulate after his awakening. Thus, while the early period of marriage and fatherhood may seem at odds with his later ascetic path, it in fact represents a crucial transitional phase: the beginning of his inner transformation from dutiful nobleman to seeker of truth.

The Four Sights and Great Departure

The story of the Four Sights — an old man, a sick person, a corpse, and an ascetic — is one of the most iconic episodes in the traditional narrative of Siddhartha Gautama’s life. According to legend, these were the first encounters that awakened Siddhartha to the realities of suffering and the impermanence of worldly pleasures, setting him on the path to renunciation.

However, from a historical-critical perspective, it is likely that the Four Sights were not literal, isolated events but rather literary and philosophical constructs. These motifs were probably retrofitted into the narrative to dramatize an internal shift in Siddhartha’s consciousness. Similar tropes are common in Indian and other religious literatures, where pivotal moments of transformation are encoded in vivid symbolic episodes. The Four Sights, then, can be understood as a narrative device meant to represent the dawning of existential awareness rather than a series of chronological experiences.

That said, the idea behind them is philosophically profound. They encapsulate the central concerns that would become the focus of Siddhartha’s teaching: the universality of suffering (dukkha), the inevitability of aging and death, and the search for a path beyond them. These themes may well have developed gradually in Siddhartha’s mind during his privileged yet inwardly disquieting life in the Śākya household.

The Great Departure — the moment when Siddhartha leaves his family and noble status behind to become a wandering seeker — marks the externalization of this internal transformation. Rather than viewing this as a sudden escape prompted by a few shocking visions, it may be more accurate to see it as the culmination of growing doubts, reflections, and inner tension. By leaving, Siddhartha aligned his outer life with an inner realization that the conventional path offered by his upbringing could not resolve the fundamental questions he was wrestling with.

Thus, the Four Sights and the Great Departure function less as literal history and more as a powerful narrative scaffold expressing the profound psychological and philosophical pivot in Siddhartha’s life.

Philosophical influences and homelessness

After his departure from the Śākya household, Siddhartha Gautama entered the world of homelessness — a state of voluntary renunciation that placed him among the many śramaṇas of his time. These wandering renunciants rejected household life and the Vedic orthodoxy, instead seeking truth through meditation, asceticism, and philosophical inquiry. His journey from noble heir to itinerant seeker placed him at the heart of one of the most intellectually pluralistic periods in Indian history.

During this phase, Siddhartha encountered several philosophical schools and teachers. He studied under Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta, both associated with forms of early meditative philosophy that likely had roots in proto-Sāṃkhya and proto-Yogic systems. These teachings emphasized the cultivation of deep meditative absorptions (jhānas) and the realization of subtle formless states of consciousness. While Siddhartha excelled under their guidance, he ultimately found these paths incomplete, as they did not offer a solution to the root of human suffering.

More broadly, Siddhartha’s early influences included the major non-Vedic schools of the time. Jainism, led by figures such as Mahāvīra, offered a rigorous path of nonviolence (ahiṃsā) and extreme asceticism as a route to liberation from karmic entanglement. The Ājīvikas, another renunciate movement, posited strict determinism and cosmic cycles governed by impersonal forces — an idea that Siddhartha ultimately rejected in favor of human agency and ethical responsibility.

Additionally, the metaphysical speculation and mystical insights of early Upaniṣadic thought would have been part of the philosophical background he encountered. These texts explored the nature of the self (ātman) and its relation to the ultimate reality (Brahman), and laid the groundwork for philosophical introspection and inner realization. Siddhartha diverged from these traditions by denying a permanent self and rejecting metaphysical absolutes, instead emphasizing impermanence, interdependence, and the cessation of craving.

Siddhartha’s early encounters with this wide range of traditions — ascetic, meditative, metaphysical, deterministic — helped shape his intellectual development. Rather than committing to any one school, he gradually formulated an independent path that synthesized what he found useful and left behind what he saw as dogmatic, impractical, or ethically deficient. This openness to inquiry, combined with direct experiential testing, would become the hallmark of his own teaching.

His homelessness, then, was not just a physical state, but a metaphor for his spiritual position: unattached to doctrines, open to insight, and committed to personal transformation. The diversity of his influences — and his ability to critically assess and transcend them — was essential to the development of what would become known as the Middle Way.

Asceticism

As part of his journey through the śramaṇa traditions, Siddhartha Gautama adopted — and ultimately rejected — extreme forms of asceticism. After studying under renowned meditative teachers, he turned to self-mortification in an effort to push the limits of physical endurance and transcend the body altogether. According to the early sources, he practiced extreme fasting, breath-holding, and other intense austerities, reducing himself to a state of near-death.

This period of radical asceticism reflected the broader śramaṇa belief that liberation could be attained by overcoming bodily desires and karmic residue through suffering and discipline. Jain and Ājīvika practitioners, for example, advocated rigorous vows, nudity, and prolonged fasting as spiritual methods. Siddhartha’s willingness to undergo such ordeals demonstrates the seriousness of his search — but also highlights a critical turning point in his thought.

Eventually, Siddhartha came to the realization that these practices were not leading to insight or liberation, but merely weakening his body and clouding his mind. This insight — recorded in the famous episode of him accepting milk-rice (piṇḍapāta) from a village girl — marked the beginning of his rejection of both indulgence and self-mortification. He concluded that truth could not be found in extremes but required a balanced and clear mind.

This turning point laid the foundation for what he would later call the Middle Way — a path that avoids both sensual indulgence and harsh asceticism. It is here that Siddhartha’s philosophy matured: not by rejecting renunciation, but by redefining it as a pragmatic path grounded in awareness, ethical conduct, and meditative practice. His departure from ascetic extremism is thus a pivotal moment in the development of Buddhist thought, marking a decisive move away from inherited dogma and toward experiential wisdom.

His awakening

Siddhartha Gautama’s awakening — often referred to in religious terms as “enlightenment” — is best understood not as a mystical or supernatural event, but as a profound insight into the nature of human experience and suffering. After abandoning extreme asceticism, Siddhartha sat beneath a tree in Bodh Gaya and resolved not to rise until he understood the root of human suffering and its cessation. What followed was not a revelation from an external power, but a deep and natural process of meditative observation, reflection, and realization.

The core of his awakening centered on the understanding of dependent origination (paṭicca samuppāda): the insight that all phenomena arise in dependence upon conditions and cease when those conditions cease. This realization was neither abstract nor metaphysical — it was experiential. He saw that suffering (dukkha) is not an inherent part of reality, but the result of craving, clinging, and ignorance, all of which are sustained by habitual mental and emotional patterns. Liberation, then, was not found by transcending the world, but by transforming one’s relationship to it through awareness, ethical action, and the cessation of reactivity.

This awakening also included the realization that there is no fixed or permanent self — an insight that challenged the core metaphysical assumptions of both Vedic and Upaniṣadic thought. Instead of a stable essence (ātman), Siddhartha saw the human experience as a dynamic interplay of impermanent processes: body, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness. This process-oriented view redefined the goal of spiritual practice as the ending of suffering through the understanding and letting go of these compounded conditions.

Thus, Siddhartha’s awakening marks the culmination of his philosophical and meditative journey — not a supernatural transformation, but a human realization with universal implications. It became the foundation for his teaching: the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. In that moment, Siddhartha did not become divine — he became awake to the nature of existence as it is.

Buddha’s turning of the wheel (first sermon)

Shortly after his awakening, Siddhartha Gautama delivered what is traditionally known as his first discourse, often referred to as the “Turning of the Wheel of Dhamma” (Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta). This moment, preserved in the early texts, is where he laid out the foundational structure of his teaching — focused not on metaphysical speculation or divine revelation, but on an experiential understanding of suffering and its cessation.

In this first address, given to five former companions from his ascetic days in the Deer Park near Sarnath, Siddhartha introduced what would later be recognized as the Four Noble Truths: the reality of dukkha (suffering or unsatisfactoriness), its origin in craving, the possibility of its cessation, and the Eightfold Path as the method to reach that cessation. These insights, while simple in form, reflect a sophisticated psychological and ethical analysis of human experience.

He also articulated the Middle Way — a path between indulgence and self-mortification — which he had discovered through personal trial and error. In doing so, he signaled a break from both the Vedic ritual tradition and the extreme renunciate practices of the time.

Although these first discourses are likely idealized in their literary presentation, they convey the early coherence and maturity of Siddhartha’s teaching. Rather than outlining a new cosmology or calling for divine worship, he offered a practical method rooted in personal investigation, ethical conduct, and meditative discipline.

This initial teaching not only won over his first followers but also established the tone for the new spiritual community that would soon form around him: one based on direct experience, inquiry, and the potential for liberation available to all. While this article does not explore the doctrinal details in depth, these foundational teachings will be treated more thoroughly in dedicated articles that follow.

Tathāgata, the Thus Come One

The term Tathāgata, often translated as “the Thus Come One” or “the Thus Gone One”, is a self-designation Siddhartha Gautama used after his awakening. While later traditions have treated this term as mystical or cosmological, its early use appears to function more as a rhetorical and pedagogical device.

By referring to himself as the Tathāgata, Siddhartha emphasized that his insights were not rooted in personal identity or ego, but arose from direct, unconditioned experience of reality as it is. It distances the speaker from conventional self-reference and invites listeners to engage with the Dhamma rather than the individual. This subtle move reflects his broader philosophical stance: there is no permanent self to elevate or worship, only the possibility of awakening through insight and ethical practice.

In historical terms, the use of Tathāgata can be understood as part of Siddhartha’s strategy to de-emphasize authority based on lineage or status. Instead, his authority came from experiential truth and the transformative potential of his teaching. His first followers

His first followers

The first followers of Siddhartha Gautama were the five ascetics with whom he had previously practiced extreme austerities. Initially skeptical of his decision to abandon self-mortification, they were convinced by his clarity and insight when he taught them the Middle Way and the Four Noble Truths. These five became the nucleus of the first sangha — a monastic community that would grow rapidly in the following years.

What made Siddhartha’s sangha unique in its time was its radical inclusivity and structure. Entry was not based on caste, social standing, or lineage, but on a willingness to follow the ethical and contemplative discipline of the path. This made the early community remarkably egalitarian, especially in the hierarchical context of ancient Indian society.

The sangha functioned as a spiritual laboratory: a collective dedicated to personal transformation, mutual support, and the preservation and transmission of the Dhamma. Decisions were often made through communal deliberation, and seniority was determined not by birth but by length of time in the order. This represented a break from both Brahmanical ritual authority and the exclusivism of other renunciate groups, and set the tone for the pragmatic and dialogical ethos of the Buddhist tradition.

Reforming cultic rituals

One of Siddhartha Gautama’s most significant contributions to the spiritual culture of his time was his decisive move away from ritualism, especially the sacrificial practices and priestly mediation that dominated Vedic Brahmanism. In contrast to traditions that emphasized offerings to deities, complex ceremonies, and hereditary access to sacred knowledge, Siddhartha shifted the focus of spiritual practice to personal ethical conduct, meditative insight, and inner transformation.

He did not condemn ritual categorically, but he redefined its relevance. Actions gained value not from their performance according to sacred formulas, but from their alignment with intention, awareness, and the reduction of suffering. This reorientation made liberation accessible not just to a privileged few, but to anyone willing to engage in disciplined reflection and ethical living.

By doing so, Siddhartha challenged the authority of the Brahmin priesthood and offered an alternative model of spiritual legitimacy: one rooted in lived experience rather than inherited roles or ritual knowledge. His teachings emphasized that insight, not sacrifice, leads to awakening — and that awakening is possible through a path that each individual must walk for themselves.

Growth of the sangha

Over the following decades, Siddhartha Gautama dedicated himself to teaching and traveling across the Gangetic plains, gradually building a diverse community of followers. The growth of the sangha was not the result of a centralized religious campaign, but of organic expansion through teaching, personal charisma, and strategic alliances with local communities, political figures, and wealthy lay supporters.

The sangha grew steadily as monks and nuns, inspired by Siddhartha’s teachings, spread the Dhamma through word of mouth and lived example. The appeal of the Dhamma lay in its practical orientation: rather than promising salvation through divine intervention or ritual, it offered a path of ethical conduct, mindfulness, and wisdom that was accessible to anyone.

Siddhartha’s decision to send out disciples in all directions — summed up in the phrase “go forth for the good of the many” — marked the beginning of a decentralized yet disciplined missionary movement. His followers traveled from village to village, teaching and living modestly, supported by lay donors who provided food, shelter, and resources in return for guidance and inspiration.

This expansion was also organizational. As the sangha grew, so did the need for internal rules, standardized practices, and methods for resolving disputes. Communities were formed in cities, forests, and rural monasteries. The teachings were preserved orally through communal recitation, and the model of a wandering but ethically disciplined community allowed the movement to maintain coherence while remaining flexible and adaptive.

By the time of Siddhartha’s old age, the sangha had become a widespread, influential network, sustained both by its ethical appeal and by the ongoing support of kings, merchants, and ordinary people. It was not a fixed institution, but a living community anchored in practice, dialogue, and shared aspiration.

Political and economic support

Among the most influential supporters of Siddhartha Gautama were King Bimbisāra of Magadha and King Pasenadi of Kosala. Their conversions and ongoing patronage not only lent political legitimacy to the sangha but also provided the practical resources necessary for its sustained expansion.

King Bimbisāra is traditionally regarded as one of the earliest royal patrons. He is said to have offered land near Rājagaha for the establishment of a monastic residence — Venuvana — thus marking one of the first instances of formal endowment to the Buddhist community. Similarly, King Pasenadi later became a close associate and supporter, often engaging Siddhartha in philosophical dialogue and expressing admiration for his teachings.

The material support of rulers was complemented by a broader network of lay donors. Wealthy merchants like Anāthapiṇḍika donated entire monastery complexes such as Jetavana, and devout laywomen like Visākhā regularly provided clothing, food, and medical supplies to the sangha. Physicians were known to offer healthcare services, and local communities built shelters and resting places for traveling monks.

This growing network of political, economic, and social support enabled the sangha to maintain a presence across diverse regions without relying on coercion or state enforcement. It allowed monastics to focus on teaching, meditation, and preserving the Dhamma, while lay supporters found in the sangha an accessible source of moral and spiritual guidance.

Ultimately, the enduring presence of the early Buddhist movement was made possible not only by the strength of its ideas but by the robust infrastructure of support built through alliances with kings, nobles, merchants, and common people alike.

Establishing rules of the order

As the sangha expanded and diversified, it became increasingly important to establish internal regulations to preserve its ethical integrity and communal coherence. Siddhartha Gautama, while continuing to teach, gradually introduced a body of disciplinary rules — later compiled as the Vinaya — to guide the behavior of monks and nuns.

The Vinaya was not handed down all at once but developed organically in response to real-life situations and challenges faced by the growing community. As new problems arose — ranging from interpersonal disputes and improper conduct to practical issues around food, lodging, and robe usage — Siddhartha addressed them through specific rules and procedures. This adaptive approach allowed the sangha to remain flexible while maintaining a shared ethical foundation.

Importantly, the rules were not meant to serve as commandments but as supports for the cultivation of mindfulness, harmony, and personal responsibility. They emphasized transparency, confession, and communal resolution of conflict, reflecting the egalitarian and dialogical ethos that characterized Siddhartha’s vision for spiritual life.

Through the establishment of the Vinaya, the early sangha transformed from a loosely connected group of wanderers into a disciplined and resilient community capable of sustaining itself over generations and across cultural boundaries.

The summer retreats

The monsoon season in northern India, marked by heavy rains and impassable roads, naturally curtailed the itinerant lifestyle of wandering monks. Rather than continuing to travel, Siddhartha Gautama and his followers began to settle temporarily in fixed locations such as groves and parks during these months. These periods of pause came to be known as vassa — the summer retreats.

What began as a practical adaptation soon became a regular part of monastic life. The rainy season retreats allowed for deeper periods of meditation, focused teaching, and community-building. They also fostered stronger ties with lay supporters, who would provide food and shelter in return for access to the Dhamma and moral guidance.

Over time, vassa became an institutionalized rhythm within the sangha, balancing movement and stillness, outreach and introspection. These retreats reflect Siddhartha’s ability to adapt the spiritual path to environmental realities, transforming a seasonal constraint into an opportunity for renewal and practice.

Admission of women

The admission of women into the sangha marked a significant, and in some ways contentious, development in the evolution of Siddhartha Gautama’s spiritual community. According to the early accounts, it was Siddhartha’s aunt and foster mother, Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī, who first petitioned to be ordained. Though initially reluctant, Siddhartha eventually allowed the formation of an order of nuns, under specific additional rules known as the garudhammas.

This moment stands as an early act of social disruption: the inclusion of women in a religious renunciate community challenged longstanding gender hierarchies in both the Vedic and śramaṇa traditions. While the additional rules imposed on nuns reflected the social limitations of the time, the very act of opening the sangha to women was a bold and transformative step.

The female sangha grew over time and produced notable teachers, poets, and practitioners whose verses are preserved in texts like the Therīgāthā. Yet, the tension between spiritual equality and social convention remained unresolved. The admission of women was a partial inclusion — groundbreaking in its possibility, but constrained in its execution.

Still, Siddhartha’s decision laid a foundation for ongoing discussions about equality, access to practice, and the role of women in spiritual life. In historical terms, it reflects both the radical vision of the Dhamma and the pragmatic negotiations with the cultural norms of the time.

The sangha and Buddhism’s social engagement

From its beginnings, the sangha drew followers from a wide cross-section of society. While early adherents included ascetics and seekers like Siddhartha’s five companions, the community quickly expanded to embrace individuals from a range of social, economic, and physical backgrounds. This openness was revolutionary in a society deeply structured by caste, ritual hierarchy, and exclusion.

Many early monks and nuns came from humble or marginalized backgrounds: artisans, farmers, servants, and even individuals considered impure or untouchable by the Brahmanical system. The sangha also welcomed those with physical disabilities or illnesses — people often ostracized in traditional society — on the basis of their capacity for ethical practice and contemplative insight rather than birth or appearance. For such individuals, the community offered not just refuge but dignity and purpose.

At the same time, wealthy merchants, landowners, and high-caste individuals also joined or supported the sangha. For the rich and powerful, the Dhamma provided a vision of renunciation and moral clarity that transcended status anxiety. Joining the order — or supporting it as lay followers — offered a way to engage in meaningful ethical and spiritual life beyond the pursuit of wealth and power.

In both its monastic and lay expressions, early Buddhism thus functioned as a socially engaged movement. It created an alternative space where spiritual worth was measured not by ritual purity or inherited status, but by conduct, mindfulness, and insight. This redefinition of value — away from caste and toward capability — became one of the most quietly radical aspects of Siddhartha Gautama’s legacy.

Siddhartha’s death and the continuation of the sangha

Siddhartha Gautama is believed to have died at the age of 80 in Kushinagar, around 400 BCE, surrounded by his disciples. According to tradition, his death was caused by a digestive illness — possibly dysentery — contracted after eating a meal offered by a local blacksmith named Cunda. The story is often told with care to absolve Cunda of blame, emphasizing Siddhartha’s acceptance of impermanence and the inevitability of death. This final episode, sometimes referred to as the “Great Passing Away” (Mahāparinibbāna), is framed in the texts as a natural and mindful end to a fully realized life.

His death (parinibbāna) was not presented in early texts as the end of a divine incarnation, but as the natural passing of a human being who had fully understood and accepted impermanence. In contrast to his mortality, the Dhamma he taught was portrayed as enduring — “decay is inherent in all compounded things; strive on with diligence,” he reportedly said in his final words.

Following his death, the sangha faced the challenge of preserving his teachings and maintaining unity. The First Council was convened shortly after his passing, traditionally held in Rājagaha under the leadership of Mahākassapa, one of his senior disciples. At this gathering, the oral recitation and memorization of Siddhartha’s teachings and monastic rules were systematized — dividing the Dhamma (doctrine) and Vinaya (discipline) for preservation. While no written texts emerged at this stage, this council laid the foundation for the later codification of the canon.

Despite these efforts, over time the sangha began to experience internal disagreements, eventually leading to the formation of different schools and interpretive traditions. These schisms, however, were less about doctrinal revolutions and more about discipline, emphasis, and practical differences in interpretation. The diversity that emerged would eventually contribute to the richness of the Buddhist tradition across Asia.

Among the general population, Siddhartha’s message continued to spread after his death, aided by the efforts of monastics and lay supporters alike. His human-centered teaching, free from ritual dependence and caste restrictions, appealed to a wide audience. Over time, successive rulers, most famously Emperor Aśoka in the 3rd century BCE, would adopt and promote Buddhism as a guiding ethical philosophy and social framework.

In historical terms, the transition after Siddhartha’s death reveals both the fragility and resilience of early Buddhism. His physical presence ended, but the sangha adapted, the teachings were preserved, and the movement continued to grow — anchored by the power of a philosophy that emphasized insight, compassion, and personal transformation.

Conclusion

We explored Siddhartha Gautama not as a divine incarnation or an unreachable mystic, but as a historical figure. By doing so, a reflective, principled human being comes into view — someone who responded creatively and courageously to the social, political, and spiritual conditions of his time. Born into a small republican clan during a period of rapid urbanization and intellectual ferment, he chose a path of homelessness and inquiry over privilege and power. His spiritual journey — through philosophical experimentation, rigorous asceticism, and eventually, contemplative insight — led to a radically new vision of human flourishing.

Rather than positioning himself as a prophet or savior, Siddhartha presented a method: a pragmatic, experience-based path for understanding and alleviating suffering. He broke decisively with the ritualism and social stratification of the dominant Vedic tradition, offering instead a path accessible to all — monastic or lay, rich or poor, man or woman. This inclusiveness, combined with his emphasis on ethics, mindfulness, and insight, made his teaching not only revolutionary but enduring.

The early sangha he established embodied this spirit. It was structured not around bloodlines or metaphysical claims, but around practice, shared inquiry, and ethical discipline. That it survived his death and grew — despite internal disagreements and external challenges — is a testament to the robustness of this vision. The careful preservation of his teachings, the adaptive development of the monastic rules, and the sustained support from laypeople and political patrons all contributed to the longevity and influence of the Buddhist tradition.

When compared to figures like Jesus — who in many traditions is presented primarily through a theological and mythologized lens — Siddhartha’s historicity stands out. The earliest sources depict him not as a divine being but as a human teacher who achieved clarity through sustained effort and insight. His mythologization came later and more gradually, layered onto an already plausible historical foundation. That Siddhartha was seen first and foremost as a person — one who overcame suffering through understanding — makes his life uniquely relatable and his message universally applicable.

Today, the significance of Siddhartha Gautama does not lie in what he claimed to be — or what others later claimed he was — but in what he discovered and shared. His teaching remains compelling not because it promises salvation, but because it offers a clear-sighted path through the complexity of human life. He challenged inherited truths, social hierarchies, and spiritual authorities — not with dogma, but with questions, practices, and a deep commitment to liberation through understanding.

In recovering the historical Siddhartha, we do not lose the Buddha — we gain a more grounded and accessible guide. His life, stripped of myth but rich with meaning, helps disentangle his actual teachings from layers of myth and devotional elaboration. By tracing his human path, we come closer to the raw philosophical core he developed: that suffering exists, that it has causes, and that it can be overcome through awareness, compassion, and ethical living.

References and further reading

- Martin G. Wiltshire, Ascetic Figures Before and in Early Buddhism: The Emergence of Gautama as the Buddha, 1990, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN: 9783110098969

- Bercholz, Samuel; Chödzin, Sherab, Buddha: Lebensweg und Heilslehre, 1999, Orbis-Verl, ISBN: 9783572100484

- Hans Wolfgang Schumann, Der historische Buddha: Leben und Lehre des Gotama, 2004, Diederichs, ISBN: 9783896314390

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

comments