Upekkhā: The role of equanimity in Buddhism

Upekkhā, commonly translated as “equanimity”, is one of the core concepts in Buddhist thought and practice. It occupies a unique position among the so-called “Four Brahmavihāras” or “Divine Abidings”, which are central ethical dispositions in Buddhist teachings. These are mettā (loving-kindness), karuṇā (compassion), muditā (empathetic joy), and upekkhā (equanimity). While the first three emphasize affective engagement with others, upekkhā introduces a balancing element, often described as serene detachment or impartiality. However, to understand upekkhā purely as emotional neutrality would be a mischaracterization. It is a nuanced concept, deeply interwoven with Buddhist philosophical anthropology, ethics, and soteriology.

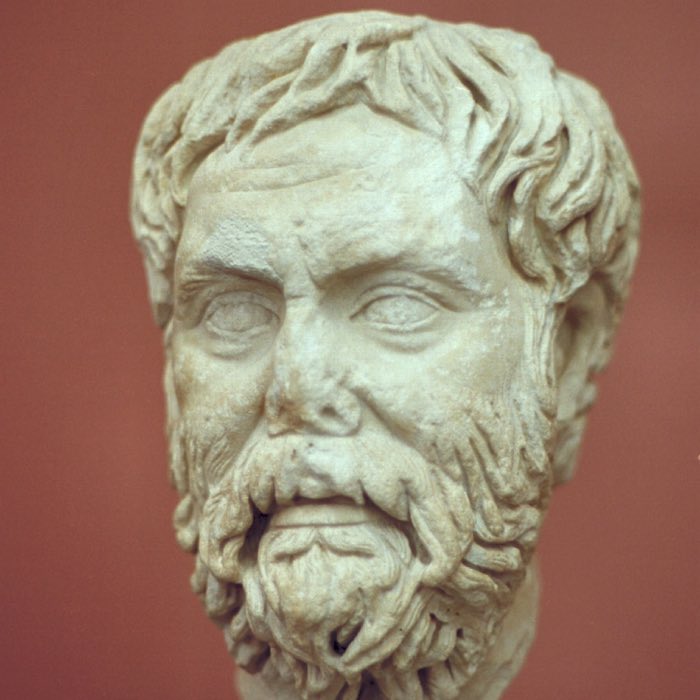

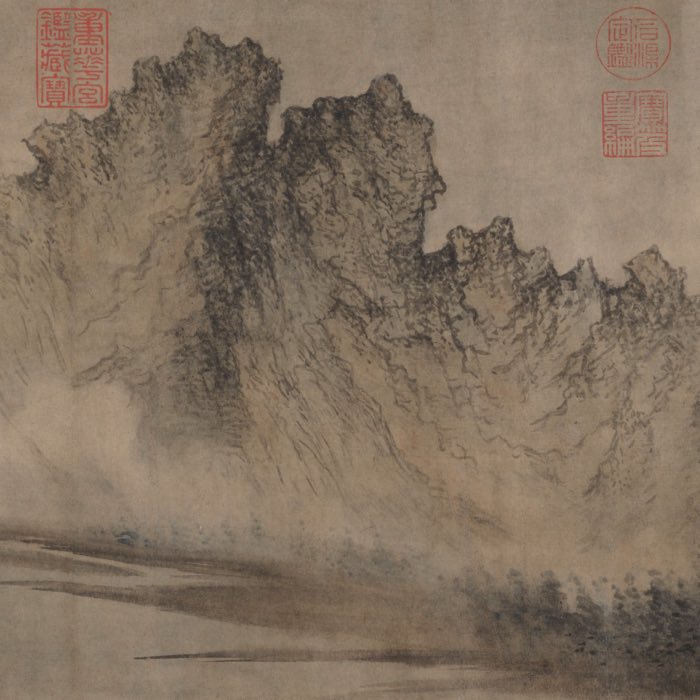

Buddha in the Preaching Attitude, fresco, 618–1279, China, Tang dynasty (618-907) - Song dynasty (960-1279). This depiction, with its serene composure and gesture of teaching, reflects the central role of equanimity (upekkhā) in Buddhist thought. The calm expression and poised posture visually embody the inner balance and clarity that characterize the awakened mind, free from attachment and aversion. Source: The Cleveland Museum of Artꜛ (license: public domain)

Buddha in the Preaching Attitude, fresco, 618–1279, China, Tang dynasty (618-907) - Song dynasty (960-1279). This depiction, with its serene composure and gesture of teaching, reflects the central role of equanimity (upekkhā) in Buddhist thought. The calm expression and poised posture visually embody the inner balance and clarity that characterize the awakened mind, free from attachment and aversion. Source: The Cleveland Museum of Artꜛ (license: public domain)

Philosophical foundations of upekkhā

In Buddhist teachings, equanimity is not merely a passive emotional state but a cultivated mental attitude grounded in insight. Siddhartha Gautama’s teachings emphasized that human suffering (dukkha) arises from attachment (taṇhā) and aversion. Upekkhā (Pāli; Sanskrit: upeksā) emerges as the antidote to these tendencies, representing a refined awareness that perceives the impermanent (anicca), unsatisfactory (dukkha), and non-self (anattā) nature of all phenomena.

Equanimity, in this sense, is epistemically informed. It results from a cognitive transformation wherein the individual recognizes the contingent and interdependent nature of experience. Rather than reacting with craving or aversion, the mind remains stable, discerning, and balanced. This mental stability is not indifference, but rather a clarity that enables ethical responsiveness without being emotionally overwhelmed.

Historical and philosophical development

While upekkhā is prominently featured in early Buddhist suttas, such as those of the Aṅguttara Nikāya, its systematic treatment evolved over time. The Abhidhamma texts of the Theravāda tradition offered a more analytical breakdown of mental states, classifying upekkhā among the wholesome mental factors that accompany purified states of consciousness. Later commentarial works such as Buddhaghosa’s Visuddhimagga further detailed its meditative function, emphasizing its refinement in the fourth jhāna and its role in counteracting emotional imbalance. This trajectory of increasingly precise definition reflects a broader trend in Buddhist scholasticism toward psychological systematization. In Mahāyāna philosophy, particularly in the writings associated with Śāntideva or the Yogācāra school, upekkhā is integrated with the Bodhisattva ideal and reinterpreted through a universalist lens.

Upekkhā in the context of the Four Brahmavihāras

Although upekkhā is often listed last among the Four Brahmavihāras, it is not a mere addendum to the other three. It plays a structural role in maintaining their ethical integrity. Without equanimity, loving-kindness may turn into attachment, compassion into sorrow, and empathetic joy into envy or partiality. Upekkhā ensures that the other three attitudes are not driven by personal bias or emotional reactivity.

In canonical sources such as the Aṇguttara Nikāya and the Dīgha Nikāya, upekkhā is associated with a vast and all-encompassing attitude toward sentient beings. The practitioner is encouraged to radiate equanimity “to all directions equally”, transcending self-centered distinctions. The Aṅguttara Nikāya (AN 10.208) expresses this orientation clearly:

He abides with a mind imbued with equanimity, abundant, exalted, immeasurable, without hostility and without ill will.

Similarly, the Dīgha Nikāya (DN 13) states that one should “dwell pervading the world with a mind imbued with equanimity, above, below, and all around, without limit.” These passages illustrate that upekkhā is not a withdrawal from the world, but an expansive and impartial engagement with all beings. This orientation supports the development of impartial concern and reflects a shift from egoic involvement to universal empathy.

The affective and cognitive dimensions of upekkhā

Upekkhā cannot be reduced to a singular psychological state. It integrates both affective and cognitive dimensions. On the affective level, it is a calm, unshakable presence that remains composed in the face of pleasure and pain, praise and blame, gain and loss, and fame and disrepute. These are known as the “eight worldly conditions” (lokadhammas), a set of dichotomous experiences that play a significant role in Buddhist ethical and psychological analysis. They are:

- gain and loss,

- praise and blame,

- fame and disrepute, and

- pleasure and pain.

These conditions are frequently referenced in the Pāli Canon, notably in the Lokavipatti Sutta (AN 8.6), where Siddhartha Gautama states that these eight experiences are naturally encountered by all beings, but the wise remain unshaken by them. The concept of lokadhammas illustrates the inherently unstable and conditioned nature of worldly life. Their recognition serves as a basis for developing equanimity, as they represent the typical triggers of emotional reactivity. In this light, upekkhā functions as the trained capacity to remain balanced and discerning, neither elated by favorable conditions nor dejected by adverse ones.

Cognitively, upekkhā is linked to the development of wisdom (paññā), which is the faculty of discerning the true nature of phenomena. In Theravāda Abhidhamma literature, equanimity is categorized as one of the fifty-two mental factors (cetasikas) and is described in terms of its function to stabilize the mind without bias or agitation. It is particularly emphasized in wholesome mental states associated with insight meditation (vipassanā), where it co-arises with mindfulness and clear comprehension. Upekkhā here functions not as passive neutrality but as a proactive mental composure that facilitates accurate observation of the three characteristics of existence: impermanence (anicca), suffering (dukkha), and non-self (anattā). The mind imbued with equanimity in this context is one that no longer clings to pleasant sensations nor recoils from unpleasant ones. Instead, it remains steady, enabling deeper penetration into the nature of reality. As such, upekkhā is not merely the absence of emotional disturbance but a cultivated state of equipoise that supports liberating insight.

Equanimity and meditative development

In the Buddhist meditative tradition, particularly in the jhāna framework (states of meditative absorption), upekkhā evolves as the meditator advances. While the initial jhānas are characterized by intense joy (pīti) and pleasure (sukha), higher stages progressively culminate in refined equanimity. In the fourth jhāna, upekkhā becomes dominant, indicating a state where even the joy of concentration is transcended, and the mind abides in perfect balance and mindfulness. This elevation of equanimity to the most refined level of meditative absorption reflects its central role in the cultivation of mental purity and non-reactivity. Because the fourth jhāna is often considered a gateway to insight and liberation, upekkhā stands at the threshold of awakening.

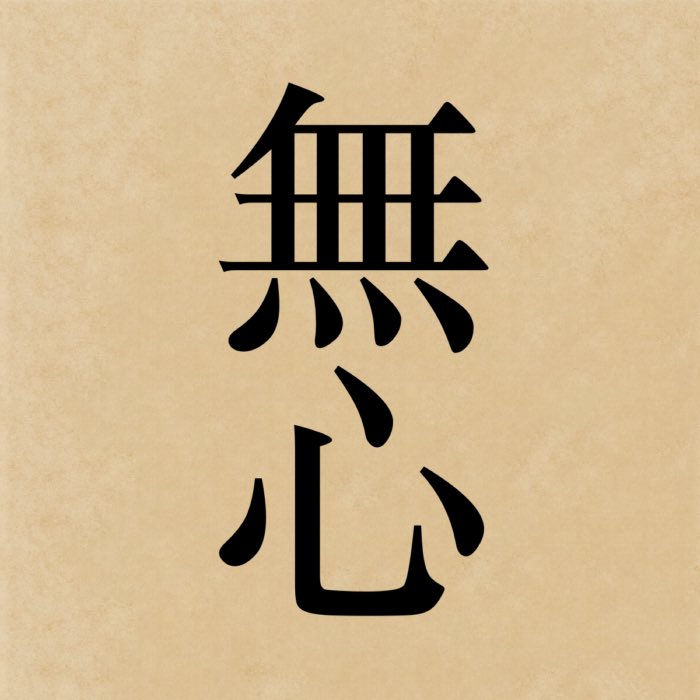

This prominence of equanimity in advanced meditative states also informs its subtle but pervasive influence in Zen Buddhism. Although Zen does not typically classify meditation in terms of jhānas, the mental qualities cultivated in zazen (seated meditation) — such as non-attachment, undisturbed clarity, and non-discriminative awareness — closely parallel the characteristics of upekkhā. In this light, equanimity can be seen as a shared core between structured absorption in early Buddhist meditation and the intuitive immediacy of Zen practice. It reflects the meditative ideal of a mind that is neither grasping nor rejecting, but fully present and free.

Beyond the jhānas, upekkhā also characterizes the culmination of insight practices. Here, it reflects the disidentification with mental formations and the cessation of reactivity. Equanimity, therefore, marks both a meditative and ethical culmination in the Buddhist path.

Ethical implications and social perception

From an ethical standpoint, upekkhā allows for just and compassionate action without emotional entanglement. It does not negate responsibility or concern; rather, it facilitates action from a position of clarity. This stance is particularly relevant in situations where intense emotions might cloud judgment. In Buddhist narratives, those who exhibit upekkhā are often portrayed as wise figures, capable of remaining calm in the face of injustice or misfortune. Prominent examples are the Buddha himself in the face of slander and assault, or King Janaka — while not a Buddhist figure, but a revered character from ancient Indian (particularly Upaniṣadic) literature — who is often portrayed as the ideal philosopher-king remaining unshaken in the midst of political turmoil and personal loss.

Socially, this can lead to differing interpretations. In cultures that value emotional expressiveness, equanimity might be misunderstood as coldness or apathy. However, within the internal logic of Buddhist ethics, it is seen as a sign of moral maturity and inner freedom. Upekkhā is the mental discipline that allows one to uphold compassion without burnout and to maintain justice without vengeance.

This becomes especially relevant in the domain of social ethics, where upekkhā has at times been critiqued for promoting detachment or even passivity in the face of injustice. Critics argue that equanimity may discourage intervention or social responsibility. However, such critiques often rest on a misreading of the concept. Upekkhā is not a call to political withdrawal, but a method of maintaining ethical clarity and inner composure amid turbulence. Rather than eliminating emotional engagement, it provides the foundation for a more sustainable form of activism.

Modern engaged Buddhist movements offer compelling examples of this reinterpretation. Figures such as Thích Nhất Hạnh and the Dalai Lama have emphasized equanimity not as withdrawal but as the steady center from which meaningful action can emerge. Upekkhā, in this context, enables practitioners to respond to systemic injustice with resilience, persistence, and compassion — rather than with anger or despair. It empowers individuals to act without hatred and to endure without emotional collapse. Thus, far from encouraging passivity, equanimity is reimagined as an ethical and spiritual resource for enduring and effective social engagement.

Comparative perspectives within Buddhist traditions

While the concept of upekkhā is consistent across Buddhist schools, its emphasis and interpretation can vary. In Theravāda Buddhism, especially in the Visuddhimagga by Buddhaghosa, upekkhā is meticulously analyzed within the Abhidhamma framework. It is both a component of meditative practice and an ethical aspiration.

In Mahāyāna traditions, equanimity is often linked with the ideal of the Bodhisattva, who cultivates boundless compassion (karuna) while remaining undisturbed by personal success or failure. Here, upekkhā functions not only as a personal virtue but as a prerequisite for universal altruism. In Zen Buddhism, equanimity is frequently associated with the non-discriminative awareness that emerges through zazen. Although not always labeled as upekkhā, the underlying principle of mental balance and non-reactivity is embedded in Zen expressions such as “letting go of all attachments.”

Cross-cultural parallels and distinctiveness

Parallels to upekkhā can be found in various philosophical traditions. The Stoic concept of apatheia and the Epicurean ideal of ataraxia both articulate visions of inner composure in the face of external circumstances. In Christian mysticism, spiritual equanimity is sometimes associated with divine surrender or faith in providence. Yet Buddhism’s treatment of equanimity is distinctive in its soteriological focus and its embeddedness in the insight into non-self. While Stoicism encourages rational self-control, and Christianity often links equanimity to divine will, Buddhism frames upekkhā as arising from experiential insight into the nature of reality itself. It is not merely a coping strategy or a spiritual state but part of the direct path to liberation.

Conclusion

Upekkhā, as explored across its philosophical, ethical, and meditative dimensions, represents a central pillar of Buddhist thought and practice. Far from being a passive or indifferent attitude, it is an active, cultivated mental quality that safeguards clarity, emotional balance, and moral discernment. Within the framework of the Four Brahmavihāras, upekkhā functions as a regulatory force, ensuring that compassion and joy do not devolve into partiality or attachment. Cognitively, it aligns with deep insight into the impermanent and conditioned nature of all experience, while in meditative contexts, it signifies the culmination of concentration and the threshold to awakening.

A critical aspect of upekkhā lies in its resistance to emotional reactivity in the face of the lokadhammas. These worldly conditions are the basic push-and-pull dynamics of ordinary life, and equanimity is the countermeasure that Buddhist teachings put forward to resist their sway. While many ethical systems in Western thought value emotional engagement, particularly in the context of justice or empathy, they often lack an equivalent concept that values non-reactivity as a virtue. Western philosophies tend to either celebrate emotional catharsis (as in some strains of Romanticism) or elevate detached rationality (as in certain Enlightenment traditions), but rarely integrate emotional composure as a path to ethical clarity. Buddhism, by contrast, sees equanimity as enhancing both insight and compassion.

In contemporary psychological discourse, the value of emotional regulation and balanced awareness is increasingly recognized — an area where Buddhism appears prescient. Practices inspired by Buddhist meditation are now being incorporated into clinical settings, and the concept of equanimity is gaining appreciation as a tool for mental well-being. However, in its original formulation, upekkhā transcends mere therapeutic goals. It is not only about reducing stress or fostering well-being, but about fundamentally transforming the way reality is perceived and responded to.

Thus, upekkhā is not simply a means of navigating life’s challenges more serenely; it is a radical reorientation of consciousness. It exemplifies a different moral psychology, one that neither represses nor indulges emotion, but integrates it into a deeper vision of non-attachment, ethical balance, and liberation from suffering.

References and further readings

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments