Prajñāpāramitā literature and the language of emptiness

The Prajñāpāramitā literature stands at the heart of Mahāyāna Buddhism, introducing the radical and transformative concept of emptiness (śūnyatā) and redefining wisdom (prajñā) as direct, non-conceptual insight into the nature of reality. Composed between the 1st century BCE and the early centuries CE, these texts challenged established Buddhist doctrines and inspired new currents of philosophical and meditative practice. In this post, we explore the origins, core themes, and far-reaching influence of the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras, highlighting their role in shaping the language, thought, and spiritual aspirations of Mahāyāna traditions across Asia.

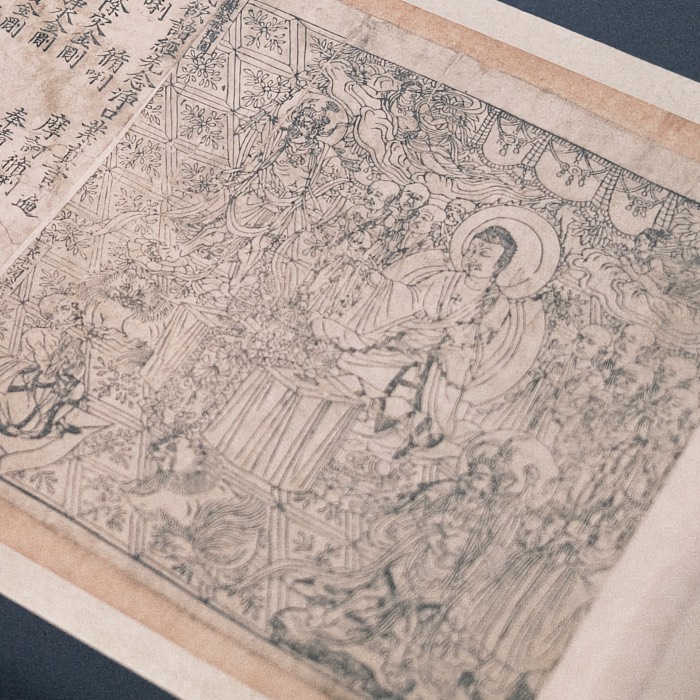

Frontispiece to the world’s earliest dated printed book, the Chinese translation of the Buddhist text the ‘Diamond Sutra’. The Diamond Sutra is a key text in the Prajñāpāramitā literature, which emphasizes the concept of emptiness (śūnyatā) and the non-duality of form and emptiness. The text is presented in a scroll format, with the frontispiece featuring an illustration of the Buddha and his disciples. The Diamond Sutra is part of a larger collection of texts known as the Prajñāpāramitā literature, which explores the nature of reality and the path to enlightenment. The scroll was printed ca. 868 CE using woodblock printing techniques, making it one of the earliest examples of this technology in action. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Introduction

The Prajñāpāramitā literature marks one of the earliest and most influential bodies of texts within Mahāyāna Buddhism. Composed over several centuries, beginning in the 1st century BCE, these sūtras introduced the core philosophical notion of śūnyatā, or emptiness, and redefined prajñā — wisdom — as direct insight into the non-substantial nature of all phenomena. Rather than promoting new metaphysical doctrines, the Prajñāpāramitā texts critically examined the limitations of conceptual thought and emphasized the necessity of transcending fixed views.

These texts played a pivotal role in shifting Buddhist discourse away from the more analytic classifications of early Abhidharma thought. They laid the groundwork for the development of Madhyamaka philosophy, particularly as systematized by Nāgārjuna, and later became doctrinally foundational for East Asian traditions such as Zen. Their influence is evident not only in philosophical formulations but also in rhetorical style and meditation practice, establishing the Prajñāpāramitā corpus as a cornerstone of Mahāyāna Buddhist thought.

Emergence of Prajñāpāramitā literature

In the context of Mahāyāna Buddhism, the Prajñāpāramitā literature represents a significant departure from earlier Buddhist texts. It is characterized by its focus on the perfection of wisdom (prajñāpāramitā) and the radical critique of conceptual thought. This literature emerged in a historical milieu marked by the rise of new Buddhist communities and the re-evaluation of established doctrines.

Early texts and dating

The Prajñāpāramitā literature began to emerge around the 1st century BCE, marking an early and distinct phase in the development of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Among the earliest texts is the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (“Perfection of Wisdom in 8,000 Lines”), which laid the foundation for a textual tradition that would expand over time into much larger versions, including those with 25,000 and even 100,000 lines. These expansions were not merely additive in length but deepened the articulation of central themes such as emptiness, non-duality, and the critique of conceptual knowledge. The process of textual accretion reflects the dynamic and evolving nature of Mahāyāna literary culture.

Historical and cultural context

The emergence of Prajñāpāramitā literature coincided with the rise of early Mahāyāna movements, which challenged and reinterpreted dominant modes of Buddhist thought and practice. In contrast to the scholastic rigor of the Abhidharma traditions — which analyzed existence into discrete, ultimately real dharmas — the Prajñāpāramitā texts denied the ultimate existence of any phenomenon, including the constituents of mind and matter. This shift can be understood as both a philosophical response and a meditative one: a reorientation from theoretical precision toward experiential insight. The literature’s critique of essentialist interpretations of reality marks a decisive break with prior frameworks and anticipates later developments in Madhyamaka and Yogācāra philosophy.

Core themes and philosophical orientation

The Prajñāpāramitā literature is characterized by several interrelated themes that form the backbone of its philosophical orientation. These include the nature of wisdom (prajñā), the concept of emptiness (śūnyatā), the critique of dualistic thinking, and the performative use of language. Each of these themes contributes to a broader understanding of the Mahāyāna path and the bodhisattva ideal.

The Six Pāramitās with emphasis on Prajñā

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, the path of the bodhisattva is defined by the cultivation of six perfections (pāramitās): generosity (dāna), ethical conduct (śīla), patience (kṣānti), energy (vīrya), meditation (dhyāna), and wisdom (prajñā). While all six are integral to the bodhisattva ideal, Prajñāpāramitā literature assigns a foundational role to prajñā, the perfection of wisdom, placing it at the heart of both realization and liberation.

Unlike conventional forms of knowledge, prajñā in these texts does not refer to analytical understanding or doctrinal mastery. It is instead characterized as a direct, non-conceptual insight into the emptiness (śūnyatā) of all phenomena. This wisdom perceives that no object, identity, or conceptual category has any inherent essence or independent existence. Because of this, true prajñā transcends binary thinking — rejecting notions of self and other, saṃsāra and nirvana, existence and non-existence.

While these formulations are central to the Prajñāpāramitā texts, they are not new inventions. The roots of such insights trace back to the earliest teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, who emphasized impermanence (anicca), non-self (anattā), and dependent origination (paṭicca-samuppāda) as the defining marks of conditioned existence. What the Mahāyāna texts contribute is not the creation of these concepts, but their expanded application and intensified emphasis, especially in the context of a bodhisattva’s path and the redefinition of wisdom itself.

By reframing prajñā in this way, the Prajñāpāramitā texts reinterpret the entire path. Ethical action and meditation remain essential, but they are ultimately aimed at enabling a shift in perception: from seeing the world in terms of solid, enduring entities to understanding it as a dynamic interplay of conditions, empty of fixed substance. In this context, the perfection of wisdom becomes not an endpoint, but a continuous mode of perceiving and engaging with reality.

Emptiness (śūnyatā)

At the heart of Prajñāpāramitā literature is the concept of śūnyatā, or emptiness. This does not denote a nihilistic void, but rather the absence of intrinsic, independent existence in all phenomena (dharmas). In this view, everything arises in dependence on causes and conditions and lacks any fixed or permanent essence. This insight extends even to the teachings themselves: not only external objects, but also ideas, concepts, and spiritual attainments are declared empty.

Again, the principle of emptiness is not a later Buddhist development. It is a continuation of Siddhartha Gautama’s fundamental insights into the contingent and conditioned nature of reality. What the Prajñāpāramitā literature adds is a rhetorical and conceptual elaboration that centers emptiness as both a philosophical and soteriological axis. The texts challenge not only metaphysical views but also the authority of language and conceptual frameworks as reliable tools for ultimate understanding.

The sūtras emphasize that there is ultimately no attainment, no self, and no fixed path. These negations serve to undermine any grasping at rigid structures or dogmatic views, including those pertaining to Buddhism itself. The bodhisattva is urged to practice without attachment even to the ideal of enlightenment. This radical position seeks to eliminate subtle forms of clinging that might arise even within spiritual striving.

Closely tied to this is the critical view of language. The texts repeatedly suggest that language and conceptual thought are limited and cannot adequately capture the nature of reality. Names and labels create distinctions that reinforce false notions of separateness and fixity. The repeated use of paradox and negation in the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras is not merely stylistic, but aims to train the reader or listener to let go of dependence on discursive thinking and open up to a direct, unmediated apprehension of emptiness.

Non-duality and paradox

A distinctive feature of Prajñāpāramitā literature is its persistent emphasis on non-duality. This principle is expressed most clearly in the rejection of dichotomous categories such as existence and non-existence, self and other, saṃsāra and nirvana. Rather than attempting to resolve these oppositions into a third term or synthesis, the texts deny the applicability of such conceptual distinctions altogether. What appears to be contradictory is instead revealed as a problem of linguistic framing and cognitive fixation.

This approach is consistent with early Buddhist efforts to transcend dualistic thinking, most notably seen in the middle path, the analysis of dependent origination, and the deconstruction of the self. In Prajñāpāramitā, these insights are rendered more explicit and elaborated through the use of radical negation. Statements such as “no eye, no ear, no nose,” or “there is no attainment” are not meant to propose new doctrines, but to dislodge the reader or listener from reliance on conceptual constructs. This anticipates later forms of apophatic discourse — the attempt to point toward truth by indicating what it is not.

The goal is not to arrive at a new metaphysical position, but to cultivate a mode of perception that does not rely on fixed views. By navigating between affirmation and negation, the practitioner is encouraged to relinquish habitual patterns of thought and open to an experiential understanding that is direct, non-conceptual, and aligned with the emptiness of all phenomena.

Style and rhetoric of the sūtras

The Prajñāpāramitā literature is characterized by a distinctive style that employs various rhetorical devices to convey its core teachings. The texts are often written in a rhythmic and repetitive manner, using formulas, paradoxes, and metaphors to engage the reader or listener. This stylistic approach serves both a pedagogical and meditative function, inviting practitioners to reflect deeply on the nature of reality and their own experience.

Repetition, paradox, and self-negation

The style of Prajñāpāramitā literature is marked by distinctive rhetorical techniques that go beyond mere content delivery. Among these, repetition plays a central role. Key formulations and themes are reiterated in rhythmic patterns, not primarily for didactic clarity but to facilitate absorption and internalization. This repetition serves a meditative function, supporting oral transmission and encouraging practitioners to engage with the text in a contemplative rather than analytical mode.

Paradox and self-negation are also prominent features. The texts frequently assert what they immediately negate, producing statements such as “all dharmas are empty, yet not destroyed” or “there is no attainment, and thus the bodhisattva attains enlightenment.” These forms of expression aim to destabilize habitual patterns of thinking and to prevent the formation of fixed conceptual views. In this way, the language itself becomes performative: it enacts the very process of deconstructing attachment to ideas and identities. Rather than presenting a coherent metaphysical doctrine, the style of the sūtras seeks to create a cognitive and experiential shift in the reader or listener.

Key metaphors and images

The Prajñāpāramitā sūtras make extensive use of metaphors drawn from ordinary experience to illustrate the insubstantial and transient nature of all phenomena. Images such as dreams, reflections in water or mirrors, echoes, mirages, and illusions are employed to convey the unreliability of appearances and the lack of inherent essence in the things we ordinarily take as real.

One of the most recognizable rhetorical formulas in the texts is of the form: “A is not A, therefore it is called A.” This seemingly contradictory structure underscores the point that while conventional labels may be used for pragmatic reasons, they do not correspond to any intrinsic reality. An illustrative example comes from the Diamond Sūtra: “All dharmas are dharma-less; that is why they are called all dharmas”. This statement denies any fixed essence to phenomena while retaining the use of language for communicative purposes, thus both affirming and undermining classification in a single gesture. The purpose of such language is not to deny phenomena outright but to loosen the grip of conceptual fixations and highlight the provisional nature of all distinctions. These metaphors and stylistic devices together form a language that aligns with the core insight of emptiness — pointing not toward new truths to be grasped, but toward the letting go of the very impulse to grasp.

Influence on later Buddhist thought

The Prajñāpāramitā literature has had a profound and lasting impact on the development of Mahāyāna Buddhism, shaping its philosophical, meditative, and ritual dimensions. The core themes of emptiness, non-duality, and the critique of conceptual thought have resonated across various schools and traditions, leading to rich interpretations and adaptations.

Nāgārjuna and Madhyamaka

One of the most consequential developments stemming from the Prajñāpāramitā literature was the Madhyamaka school of philosophy, founded by Nāgārjuna in the 2nd century CE. Nāgārjuna systematized and defended the concept of śūnyatā (emptiness) through rigorous philosophical reasoning, effectively translating the rhetorical and soteriological themes of the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras into a coherent philosophical framework. Rather than presenting emptiness as a metaphysical substance or ultimate reality, Nāgārjuna maintained that all things are empty of svabhāva (intrinsic existence) precisely because they arise dependently (pratītyasamutpāda).

A central contribution of Madhyamaka is the doctrine of the Two Truths: conventional truth (saṃvṛti-satya) and ultimate truth (paramārtha-satya). This distinction clarified how language and conceptual thought can function in ordinary contexts while ultimately failing to capture the true nature of reality. The use of paradox and negation in the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras thus finds philosophical grounding in Nāgārjuna’s argumentation, which reveals that all assertions — positive or negative — are empty when pressed beyond their conventional use.

In this way, Madhyamaka not only preserved the central insights of the Prajñāpāramitā texts but provided them with intellectual robustness that enabled their transmission and integration across later Buddhist traditions. Nāgārjuna’s work allowed the concept of emptiness to become a foundational element of Mahāyāna thought, influencing both the scholastic and meditative dimensions of Buddhist practice.

Tathāgatagarbha and Buddha-nature thought

The emergence of the Tathāgatagarbha doctrine — often translated as Buddha-nature — introduced a significant current into Mahāyāna Buddhism that, at first glance, appears to diverge from the radical negation found in Prajñāpāramitā literature. Whereas the language of emptiness emphasizes the absence of inherent essence in all phenomena, Buddha-nature teachings speak of an underlying potential or intrinsic capacity for awakening present in all beings. This language has sometimes been interpreted as reintroducing a form of essentialism, leading to doctrinal tension.

However, many Buddhist thinkers in both India and East Asia sought to reconcile these strands. Rather than treating Buddha-nature as a substantial self or metaphysical ground, they interpreted it as a skillful means of describing the capacity for awakening that becomes apparent when delusions and conceptual fabrications are seen through. In this reading, the Buddha-nature is not a hidden core but a metaphor for the emptiness of defilements and the clarity that arises when they are absent.

Such integrations are evident in texts like the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, which frames Buddha-nature as empty of defilements but not of awakening. Similarly, East Asian interpretations — especially in the Chán/Zen tradition — often identify Buddha-nature with the very insight into emptiness itself. Far from being contradictory, the two perspectives can be seen as complementary: emptiness describes the ontological openness of reality, while Buddha-nature emphasizes its practical and transformative potential when perceived clearly.

Chán/Zen Buddhism

The influence of Prajñāpāramitā literature on the development of Chán (Zen) Buddhism is most visible in the shared emphasis on non-conceptual insight and the limitations of discursive thought. Zen’s core practice of zazen (seated meditation) and its emphasis on direct, experiential realization of reality align closely with the Prajñāpāramitā vision of prajñā as a wisdom that transcends language and conceptual constructs. Zen inherits the foundational idea that awakening cannot be grasped through intellectual analysis but must be directly perceived.

This continuity is further expressed in the use of kōans — short, paradoxical dialogues or statements used to disrupt ordinary thinking and provoke intuitive insight. The logic behind kōans reflects the rhetorical strategies of the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras: the use of negation, paradox, and seemingly nonsensical formulations to break attachment to fixed views. Just as the sūtras declare, “form is emptiness, emptiness is form”,” kōans destabilize the practitioner’s conceptual expectations and point toward a deeper, pre-conceptual understanding.

Zen also inherits the performative aspect of Prajñāpāramitā discourse. In both, language is used not to describe truth, but to dislodge the listener from the tendency to grasp after it. This shared orientation situates Zen as a natural, though distinct, expression of the Prajñāpāramitā tradition — one that maintains fidelity to its core insight while reconfiguring it in the context of Chinese and Japanese cultural, linguistic, and institutional forms.

The Heart Sūtra and Diamond Sūtra

Among the extensive Prajñāpāramitā corpus, two texts have achieved particular prominence due to their concise format and broad ritual adoption: the Heart Sūtra (Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya) and the Diamond Sūtra (Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā). Both distill the complex philosophical content of the larger Prajñāpāramitā texts into highly compact forms, making them accessible for memorization, recitation, and meditative reflection. Despite their brevity, these texts preserve the central themes of emptiness, non-attachment, and the limitations of conceptual thought.

The Heart Sūtra, possibly the most widely recited Mahāyāna scripture, is structured as a dialogue between the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara and the monk Śāriputra. It famously declares, “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form,” encapsulating the core teaching that all dharmas lack inherent existence but are not separate from lived experience. The text also features the “denial formula” listing the absence of sensory faculties, cognitive elements, and even the Four Noble Truths — emphasizing the non-substantiality of all categories used in Buddhist practice.

The Diamond Sūtra employs a similar strategy of negation and paradox, often using the rhetorical formula “A is not A, therefore it is called A” to subvert conventional designations. For example, it states: “A bodhisattva should develop a mind that does not dwell anywhere,” urging non-attachment even to virtuous qualities or goals. This text was among the earliest printed books in the world and played a significant role in Chinese Buddhist education and textual culture.

Both sūtras became integral components of East Asian Buddhist liturgy and training. Their memorization and daily recitation are not merely devotional acts but are intended to deepen the practitioner’s familiarity with the language of emptiness and to support meditative insight. Over time, they came to symbolize the heart of the Mahāyāna view — not as doctrinal summaries, but as practical tools for internalizing a mode of seeing that breaks through the illusion of fixed reality.

Conclusion

The Prajñāpāramitā literature has had a profound and enduring influence on the evolution of Mahāyāna Buddhism and its transmission across cultural and historical contexts. Its core insights — emptiness, the non-conceptual nature of wisdom, and the critique of language — have shaped philosophical traditions such as Madhyamaka, informed the development of Zen and other East Asian schools, and continue to resonate with contemporary readers seeking a non-essentialist and process-oriented view of reality.

One of the most distinctive contributions of these texts is their ability to challenge the very tools they employ — language and conceptual thought — while still using them to point toward a transformative understanding. This paradoxical stance has demanded careful interpretive engagement from every generation of readers, inviting practitioners not merely to understand but to unlearn, not merely to define but to experience directly.

Crucially, emptiness as presented in the Prajñāpāramitā tradition is not a denial of reality or a lapse into nihilism. It is an invitation to recognize the interdependent, impermanent, and contingent nature of all phenomena. By undermining the tendency to fixate on concepts, identities, or metaphysical claims, the literature offers a path toward cognitive freedom and ethical responsiveness. In this way, the legacy of the Prajñāpāramitā corpus is not only philosophical but deeply practical — shaping how individuals see the world, relate to others, and understand themselves within an ever-shifting field of conditions.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Prajna, Zen und die Höchste Weisheit, Die Verwirklichung der „transzendenten Weisheit” im Buddhismus und im Zen, 1. Januar 1990, O. W. Barth, ISBN-10: 3502645981

comments