The student-teacher relationship in Zen

The relationship between student and teacher in Zen Buddhism is not merely instructional; it is transformative. Unlike conventional forms of religious education or academic mentorship, the Zen student-teacher bond centers on the direct transmission of insight, often beyond words or formal doctrine. The teacher does not function as a distant authority imparting knowledge, but as a mirror, guide, and provocation. Their role is to accompany the student to the edge of self, to challenge pretense, and to foster awakening through encounter.

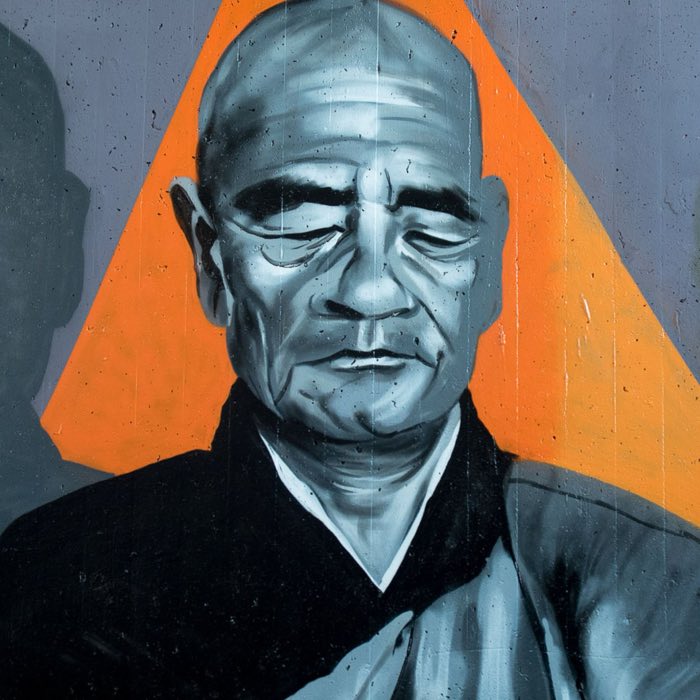

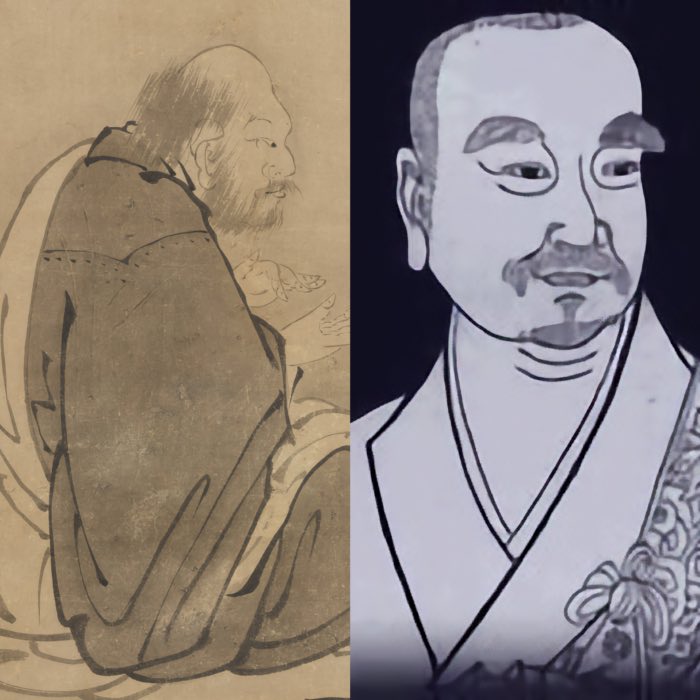

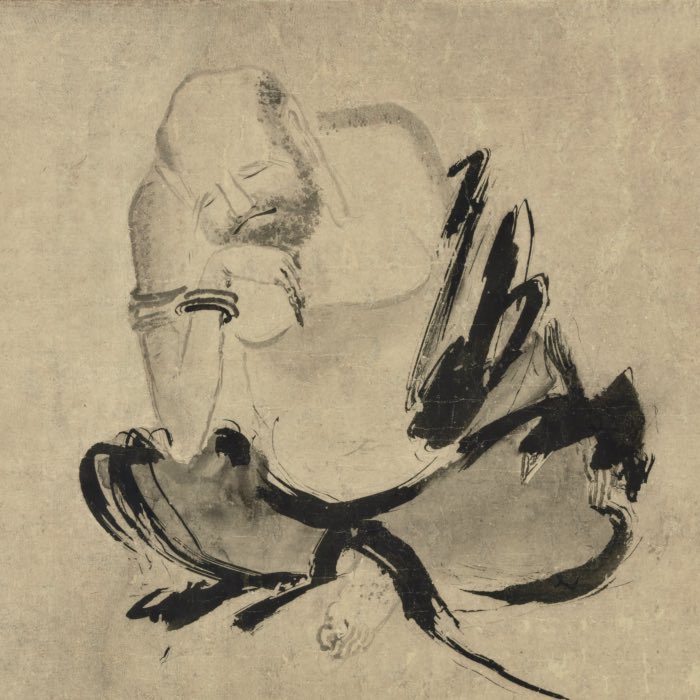

Huangbo Xiyun (left) and his student Linji Yixuan (right). Linji, who later became the founder of the Linji school of Chán, is known for his direct and often confrontational teaching style, which emphasizes the importance of personal experience and direct realization. Huangbo, on the other hand, represents a more subtle and nuanced approach to Zen teaching. The dynamic between these two figures illustrates the complexity of the student-teacher relationship in Zen, where both challenge and support are essential for awakening. Source left: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain), source right: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

This unique relationship forms the backbone of Zen training and is enshrined in the tradition’s ideal of “mind-to-mind transmission” (Japanese: ishin denshin, Chinese: yixin chuanxin 意心传心), believed to trace back to the Buddha’s silent transmission to Mahākāśyapa. From this mythic origin onward, Zen has emphasized that true understanding is not found in scripture alone, but in the shared silence, tension, and realization between teacher and student.

The teacher’s role: Provoker of insight

In Zen, the teacher (Japanese: rōshi, Chinese: laoshi or chanshi) is not primarily a lecturer or spiritual counselor. Their job is to catalyze awakening. This may involve presenting a kōan (公案), confronting the student in an interview (dokusan), or issuing seemingly paradoxical challenges meant to undermine the student’s reliance on conceptual thought.

The teacher must balance compassion with severity. They may appear harsh or abrupt, not out of disdain but to break through the student’s attachment to ego and reasoning. Famous stories of Zen masters shouting, striking, or responding with silence are not performances of eccentricity but expressions of a deep pedagogical strategy: to bring the student to a state of direct, unmediated seeing.

The student’s role: Receptivity and determination

The Zen student (Japanese: unsui or shugyōsha) must come with a sincere intention to practice and the courage to be transformed. This involves more than passive acceptance of a teacher’s words; it requires vulnerability, openness to challenge, and a willingness to relinquish the safety of fixed views.

A Zen student’s sincerity is often tested. The tradition includes stories of students demonstrating extreme devotion and perseverance before being accepted by a master. The point is not asceticism for its own sake, but a demonstration of resolve and trust. The student must be ready not just to receive teachings, but to undergo a process that may dismantle their self-image entirely.

Encounter as method: The practice of dokusan

A hallmark of Zen pedagogy is the private interview between student and teacher, known as dokusan (or sanzen in some traditions). In these brief, direct encounters, the student may present their response to a kōan, report their meditative experience, or receive a spontaneous question.

Unlike typical teacher-student dialogues, dokusan is not aimed at exchanging information. It is a space of raw encounter, where the teacher reads not only the student’s words but their state of being. Here, realization is tested, not by doctrinal correctness but by authenticity. One may pass a kōan not by explanation, but by an intuitive gesture, a silence, or a word uttered from genuine insight.

Risks and ethics in the Zen hierarchy

Given the intense intimacy and power asymmetry in the Zen student-teacher relationship, ethical integrity is paramount. While the tradition values radical methods and boundary-pushing exchanges, it also carries the risk of abuse or misunderstanding. Modern Zen communities have had to grapple with cases where authority was misused under the guise of spiritual transmission.

Ethical guidelines, transparent communities, and mechanisms for accountability are essential in contemporary practice. The true function of a teacher is not to dominate or mystify, but to liberate. Reverence should never become dependency, and critique should never be mistaken for disrespect. A healthy student-teacher relationship in Zen is dynamic, transparent, and grounded in mutual respect and clarity of intention.

Practicing Zen without a formal teacher

Zen has always upheld the ideal of direct, experiential realization — something that can, in principle, occur outside monastic hierarchies. Figures like Vimalakīrti, the lay Bodhisattva who outshone even the Buddha’s foremost disciples, exemplify this possibility. Huineng (638–713), the Sixth Patriarch, himself came from a lay background, illiterate and working-class, and was recognized for his awakening rather than any scholastic or institutional status. These examples underscore a longstanding theme in Zen: that awakening is not confined to ordained settings or formal transmission. While teachers and lineages have played a central role in preserving and transmitting the Dharma, the tradition also holds space for those who realize the truth directly — guided by practice, integrity, and deep personal engagement with the teachings.

Contemporary contexts and motivations

In the modern world, many sincere practitioners are geographically or culturally distant from traditional Zen temples or teachers. Others may prefer a less hierarchical mode of practice, valuing autonomy and self-direction. While the role of a teacher remains profound, especially in providing feedback and challenge, its absence does not necessarily block the path. Many have found meaningful and transformative engagement with Zen through close study of foundational texts, committed solitary zazen, and active participation in sangha communities, whether in person or online. Such practice requires both discipline and discernment, as the practitioner becomes their own guide and witness.

Guidelines for self-practice

For those walking the Zen path without a personal teacher, a few principles can help:

- Consistency: Regular zazen is foundational. Even brief, daily sitting cultivates clarity and presence.

- Companion texts: Foundational works such as The Platform Sutra, Shōbōgenzō, and Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind offer deep guidance when read reflectively.

- Community: Practicing alone need not mean isolation. Online sangha, retreats, and discussion forums can offer support and accountability.

- Humility and skepticism: Without a teacher’s feedback, it is easy to mistake conceptual insights for realization. Maintain an open and questioning attitude.

Challenges and cautions

Practicing without a teacher carries real risks:

- Misinterpretation of key teachings (especially kōans)

- Reinforcement of ego-driven views under the guise of insight

- Difficulty navigating plateaus or crises in meditation

For this reason, even if one begins alone, it may be wise to seek guidance when the opportunity arises, whether through a one-time retreat, a correspondence, or periodic consultation.

Conclusion

The Zen student-teacher relationship is foundational to the tradition’s unique mode of transmission. It is not based on the delivery of information, but on a mutual engagement that challenges, unsettles, and ultimately opens the path to direct realization. In this context, the teacher acts not as an authoritarian figure but as a provoker of awakening, while the student is not a passive recipient but a committed practitioner ready to face the uncertainty of self-transformation.

We have seen that Zen pedagogy is rooted in encounter, in face-to-face moments of unguarded presence that defy conceptual knowing. The method of dokusan, the testing of insight through kōans, and the unpredictable exchanges between master and student all serve to bring forth a realization that cannot be inherited or mimicked.

Yet this intensity carries risks. The power imbalance inherent in such relationships demands deep ethical awareness. When handled responsibly, the student-teacher bond can be a site of profound liberation. When misused, it can lead to harm and confusion. Modern Zen communities must continue to engage critically with this legacy, preserving what is essential while cultivating transparency and accountability.

Importantly, Zen also leaves space for those who walk the path without a formal teacher. The examples of awakened lay figures, the accessibility of foundational teachings, and the rise of lay sanghas demonstrate that direct realization is not the exclusive domain of institutional training. While the guidance of a teacher can be invaluable, its absence does not preclude sincere practice, especially when supported by discipline, humility, and community. What matters most in the end is not whether one has a teacher, but whether one sees clearly.

Ultimately, the strength of the Zen student-teacher relationship lies in its paradox: it is both personal and impersonal, intimate yet beyond personality. It points beyond the teacher, beyond the student, to the moment of awakening that transcends both. In that shared silence where words fall away, the mind may just see its own nature.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki (Autor), C. G. Jung (Einleitung), Felix Schottlaender (Übersetzer), *Die große Befreiung. Einführung in den Zen-Buddhismus *, 2003, Otto Wilhelm Barth, 20. Auflage, ISBN-10; 3502675945

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Zen und die Kultur Japans, 1970, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg

comments