Hakuin Ekaku and his role in the revitalization of Rinzai Zen

Among the many figures in the history of Zen Buddhism, few have had as lasting an impact as Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1769). Active during the Edo period in Japan, Hakuin is often credited with reviving and reshaping the Rinzai school (Rinzai-shū) of Zen, which had, by his time, fallen into stagnation and formalism. Through his emphasis on rigorous training, kōan practice, and the integration of Zen insight into daily life, Hakuin reenergized a tradition that would come to define Japanese Zen for centuries to follow. In this post, we explore Hakuin’s teachings, his innovations in Zen practice, and his role in reaffirming the vitality of the Rinzai tradition.

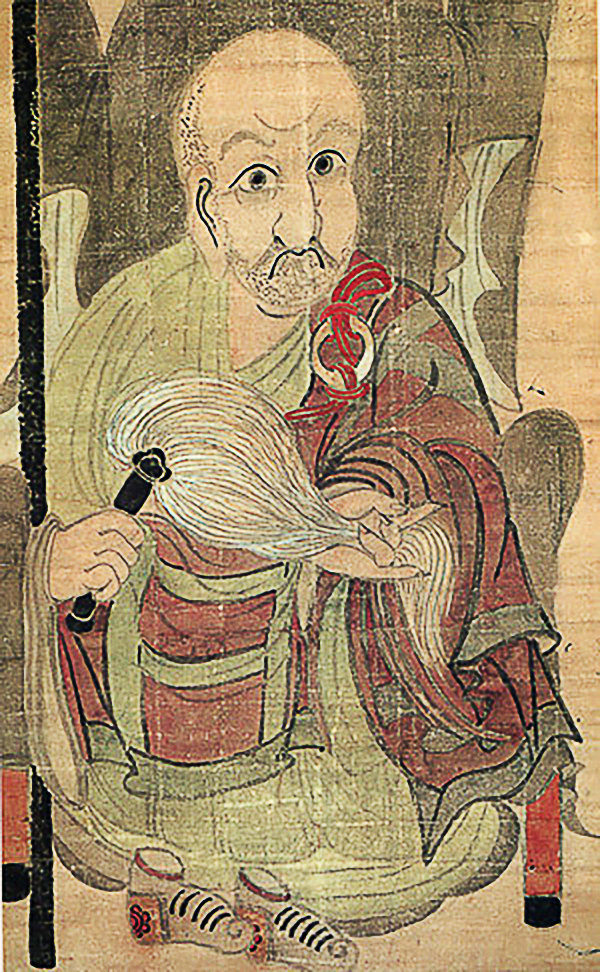

Self-portrait of Zen master Hakuin Ekaku (白隠 慧鶴, 1686–1768), 1767. Hakuin pursued a vigorous and dynamic style of Zen practice, emphasizing the integration of awakening into daily life. His teachings and methods revitalized the Rinzai tradition, making it accessible to a broader audience. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Hakuin’s life

Early life

Hakuin was born in 1686 in the small village of Hara at the foot of Mount Fuji. His mother was a devout Nichiren Buddhist, and her piety likely had a significant influence on Hakuin’s early religious orientation. As a child, Hakuin attended a lecture by a Nichiren monk on the Eight Hot Hells (naraka), which deeply impressed and terrified him. Determined to escape such a fate, he concluded that becoming a Buddhist monk was necessary.

At the age of fifteen, with his parents’ approval, Hakuin was ordained at Shōin-ji, a local Zen temple. When the head monk there fell ill, Hakuin was transferred to Daishō-ji, where he served as a novice for three or four years, studying Buddhist texts. During his time at Daishō-ji, he read the Lotus Sutra, highly revered in Nichiren Buddhism, but found it disappointing, describing it as “only simple stories of cause and effect”.

At eighteen, Hakuin moved to Zensō-ji near Hara. At nineteen, he encountered the story of the Chinese Chán master Yantou Quanhuo, who was brutally murdered by bandits. This encounter led Hakuin into a crisis of faith; if even great masters were not spared a violent death, how could he hope to attain salvation? Disillusioned, he abandoned his goal of becoming an enlightened monk and turned to the study of literature and poetry.

Later, traveling with twelve other monks, he arrived at Zuiun-ji, the residence of Baō Rōjīn, a respected scholar and rigorous teacher. During his stay, Hakuin experienced a pivotal moment: he saw a stack of books from various Buddhist schools in the temple courtyard. Praying to the gods of the Dharma for guidance, he reached out and picked a book at random, which was a collection of Zen stories from the Ming dynasty. Deeply moved, Hakuin repented and renewed his commitment to Zen practice.

First awakening

After renewed dedication, Hakuin traveled again for two years and eventually settled at Eigen-ji at the age of twenty-three. At twenty-four, he experienced his first breakthrough into awakening. He confined himself for seven days in a shrine at the temple, and finally, upon hearing the sound of the temple bell, he had a profound awakening experience. However, his master at Eigen-ji refused to recognize this enlightenment, prompting Hakuin to leave.

Study with Shōju Rōjin

Hakuin then studied for eight months under the fierce and demanding teacher Shōju Rōjin (Dokyu Etan, 1642–1721). Shōju subjected Hakuin to relentless verbal and physical challenges, aiming to shatter his ego and superficial understanding. When Hakuin explained that he had become a monk out of fear of hell, Shōju retorted, “You are a self-centered rascal, aren’t you?” Shōju assigned Hakuin a series of difficult kōans, leading to three isolated moments of satori (awakening). However, it would take Hakuin another eighteen years to fully comprehend what Shōju had pointed toward.

Hakuin left Shōju without receiving formal Dharma transmission at that time, but he regarded himself as Shōju’s spiritual heir. Today, it is generally accepted that Hakuin did, in fact, receive transmission from Shōju Rōjin.

Great Doubt and further practice

Although Hakuin had experienced satori, he realized that his attainment was incomplete. He struggled to maintain the peace of mind gained in the meditation hall during the activities of daily life. At twenty-six, reading that even wise monks without the Bodhi-mind fall into hell, he was struck with “Great Doubt” (taigi). He had believed that formal ordination and ritual practice sufficed for salvation. Only much later, at the age of forty-two, did he fully grasp that true Bodhi-mind meant working for the welfare of others.

Zen sickness and healing

His early intense practices also took a heavy toll on his health. Hakuin suffered what would today likely be diagnosed as a nervous breakdown. Calling it “Zen sickness”, he sought the help of a Daoist hermit named Hakuyu, who prescribed visualization and breathing exercises. These methods restored Hakuin’s vitality and shifted his focus: henceforth he emphasized physical health and endurance as vital parts of Zen practice. “Nurturing the soft butter” meditation, based on Hakuyu’s teachings, remains part of the Rinzai tradition today.

Return to Shōin-ji and mature awakening

At thirty-one, Hakuin returned to Shōin-ji, where he had been ordained, and became its head priest, a position he held for over fifty years. Around this time, he adopted the name “Hakuin”, meaning “hidden in the white”, a reference to being concealed in the snows and clouds of Mount Fuji.

Despite several earlier satori experiences, Hakuin still felt his realization was incomplete. At forty-one, while reading the Lotus Sutra, the very scripture he had once dismissed, he underwent a final, total awakening. He understood that the true meaning of the Bodhi-mind is the practice of tirelessly helping all beings attain liberation.

Teaching and legacy

For the next four decades, Hakuin taught at Shōin-ji, wrote prolifically, and attracted hundreds of disciples. His fame grew, and Hara village became a vibrant center of Zen learning. Ultimately, he certified over eighty disciples as successors.

During this period occurred the famous “Is That So?” incident. Wrongly accused of fathering a child, Hakuin accepted the blame with equanimity, cared for the child, and later returned the baby to its family when the truth emerged. His simple refrain, “Is that so?”, exemplified the equanimity he embodied.

Hakuin died in 1769 at the age of eighty-three, in the same village where he was born, leaving behind a revitalized Rinzai tradition that continues to shape Zen to this day.

Teachings

Dynamic integration of practice and daily life

Hakuin insisted that true Zen realization must be brought into the activities of everyday life. He criticized practitioners who could maintain clarity only in the meditation hall but faltered in daily affairs. For Hakuin, enlightenment was worthless if it could not function amid the demands and frictions of the world. Training, therefore, must aim at dynamic integration: clear awareness and compassionate action in the midst of ordinary life.

For Hakuin, initial awakening (satori) was only the beginning. He stressed the indispensable importance of “post-satori training”, i.e., the ongoing purification of karmic tendencies and the deepening of insight through continuous exertion. Awakening must lead to arousing bodhicitta, the Mind of Enlightenment, characterized by deep compassion and the vow to save all sentient beings. Hakuin taught that after realizing satori, practitioners should “whip forward the wheel of the Four Universal Vows”, dedicating every moment to benefiting others through the Dharma. He wrote, “What is to be valued above all else is the practice that comes after satori is achieved”.

Hakuin’s final and total awakening at the age of 41 confirmed this insight, making the post-awakening practice the true heart of the Zen path in his teaching. True awakening, in Hakuin’s view, was not an endpoint, but the beginning of a lifelong effort to embody enlightenment in compassionate activity. Through his energetic teaching, innovative methods, and outreach to the broader society, Hakuin Ekaku revitalized Japanese Rinzai Zen, leaving a living legacy that continues to inspire practitioners today.

Four ways of knowing and the Four Gates

Hakuin integrated elements of Yogācāra thought into his Zen system. He adopted the framework of four types of knowledge introduced by Asaṅga:

- Perfecting of Action

- Observing Knowledge

- Universal Knowledge

- Great Mirror Knowledge

These correspond to the eight consciousnesses, culminating in the transformation of perception into enlightened wisdom. Hakuin linked these types of knowledge to four stages on the Zen path, which he called the Four Gates:

- Gate of Inspiration: Initial awakening or kenshō.

- Gate of Practice: Continuous purification through disciplined practice.

- Gate of Awakening: Deepening understanding through the study of sutras and the sayings of the masters, enabling skillful guidance of others.

- Gate of Nirvana: Final liberation, complete untainted knowledge.

Through these stages, Hakuin emphasized that Zen realization is not static but an unfolding process, grounded in both personal transformation and compassionate engagement with the world.

Reviving kōan practice

One of Hakuin’s greatest contributions was the revitalization of kōan practice. At his time, many Rinzai temples had reduced kōans to mere academic exercises. Hakuin reintroduced kōans as existential challenges aimed at shaking students free from intellectualization. He strongly believed that only through relentless meditation on a kōan could a student become one with it and achieve awakening. Hakuin emphasized that the psychological tension and Great Doubt arising from wrestling with a kōan were critical, writing: “At the bottom of great doubt lies great awakening. If you doubt fully, you will awaken fully”.

He devised a systematic fivefold classification of kōans:

- Hosshin (Dharma-body kōans): Used to awaken initial insight into śūnyatā (emptiness), introducing the undifferentiated and unconditional.

- Kikan (Dynamic action kōans): Aimed at helping students understand the phenomenal world from the standpoint of awakening, representing function (yu) as opposed to essence (tai).

- Gonsen (Word-explanation kōans): Focused on clarifying the sayings of ancient masters, illustrating how the fundamental truth can be expressed through words without clinging to them.

- Hachi Nanto (Eight “hard to pass” kōans): Designed to cut through attachment to previous realization and spark further Great Doubt, deepening insight.

- Goi Jujukin (Five Ranks and Ten Grave Precepts kōans): Used for advanced training in harmonizing the absolute and the relative.

Hakuin was not limited to the classical Chinese collections; he also created new kōans, such as the famous “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” He preferred this over the traditional “Mu” kōan, believing it to stimulate Great Doubt more effectively, saying it surpassed older methods “as cloud surpasses mud”. Hakuin’s revitalized kōan curriculum had a lasting impact on Rinzai Zen and remains central to its training today.

Opposition to “Do-Nothing Zen”

Hakuin strongly opposed what he called “do-nothing Zen”, a quietistic trend among some Zen groups who advocated merely sitting without effort, discipline, or critical introspection. He criticized practices that sought simply to empty the mind or equated tranquil “emptiness” with enlightenment, targeting especially the followers of maverick Zen master Bankei. Bankei, who lived from 1622 to 1693 and, thus, one generation before Hakuin, taught a form of Zen that emphasized the “Unborn” mind, which he claimed was already present in everyone. Hakuin saw this as a dangerous oversimplification that could lead to complacency and stagnation. Hakuin insisted that genuine satori required vigorous exertion, relentless questioning, and active engagement with kōans, fueled by the psychological tension of “Great Doubt”. He stressed the need for continuous and severe training to deepen the initial insight of satori and forge the ability to manifest it fully in all activities. He urged students never to be satisfied with shallow attainments, believing deeply that true enlightenment was attainable for anyone who exerted themselves with real energy and unwavering resolve.

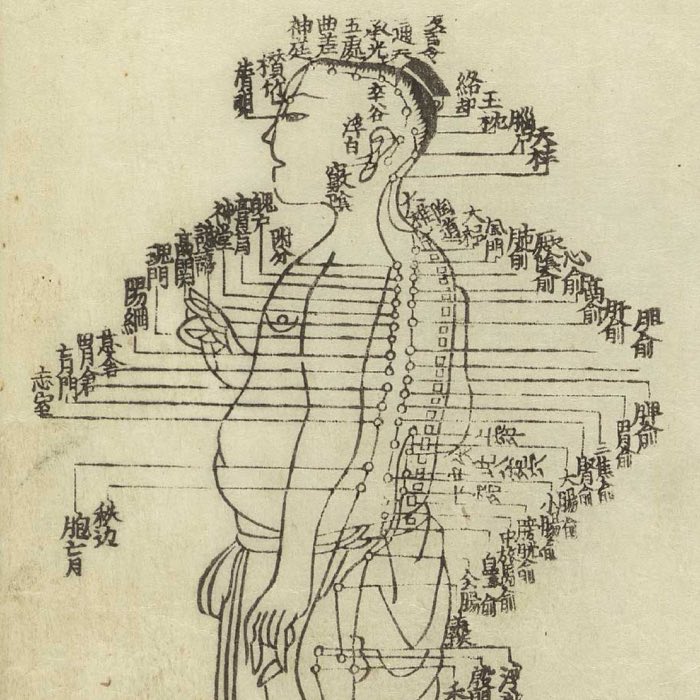

Zen-sickness and vital energy

During his rigorous early practice, Hakuin experienced severe physical and mental exhaustion, a condition he referred to as “Zen sickness” (zenbyō). Seeking a cure, he encountered Hakuyū, a Taoist hermit, who taught him two restorative methods: ‘introspective meditation’ (naikan), using abdominal breathing and focusing on the hara (lower abdomen), and a visualization called the ‘soft butter method.’ According to later scholarship, this Zen-sickness likely occurred when Hakuin was in his late twenties. Some conjecture that these remedies were worked out by Hakuin himself, drawing from a mixture of traditional medical, meditation, and folk therapies.

In his text Yasenkanna (“Idle Talk on a Night Boat”), Hakuin elaborates on these methods. In its preface, attributed to a disciple called “Hunger and Cold, the Master of Poverty Hermitage”, it is explained that longevity can be attained by gathering the Qi, the vital life-force or “the fire or heat in your mind (heart)”, into the tanden or lower belly, producing the “true elixir” (shintan), which is “not something located apart from the self”. Hakuin describes a four-step introspective practice for concentrating Qi in the tanden:

- Recognizing the tanden as one’s “true and original face”, beyond physical features.

- Realizing the tanden as the home and native place of original being.

- Understanding the tanden as the Pure Land of one’s own mind.

- Knowing the tanden as the embodiment of Amida Buddha within the self.

This naikan method contrasts with the “soft butter method”, in which one visualizes a lump of soft butter melting slowly from the top of the head, spreading warmth and relaxation through the entire body.

While Hakuin emphasized the importance of physical health for practice, he warned that longevity itself was not the ultimate goal of Buddhism. True practice was measured by the commitment to the Bodhisattva ideal: “constantly working to impart the great Dharma to others as you acquire the imposing comportment of the Bodhisattva”. In Yasenkanna, Hakuyū further explains the importance of “bringing the heart down into the lower body”, distinguishing “false meditation”, which is distracted and unfocused, from “true meditation”, which is seamless and without deliberate contrivance. Drawing from Buddhist sources and Chinese medicine, Hakuin presents a unique synthesis of spiritual and physical cultivation that had a lasting influence on later Rinzai Zen training.

Lay teachings

Hakuin was in his later life an extremely popular and revered Zen master who firmly believed in making the wisdom of Zen accessible to — and practicable by — all people. Thanks to his upbringing as a commoner and his many travels throughout the country, he could easily relate to the rural population, serving as a kind of spiritual father to the people living near Shōin-ji. Indeed, he declined invitations to serve in major temples in Kyoto, preferring instead to remain at Shōin-ji among the common people. Much of his instruction to laypersons focused on living a morally virtuous life, combining elements from Confucian ethics, traditional Japanese values, and Buddhist teachings. Despite the polemical tone found in some of his writings against other Buddhist schools, Hakuin never tried to dissuade rural folk from following non-Zen traditions.

Moreover, Hakuin became a popular Zen lecturer, frequently traveling across Japan, including trips to Kyoto, to teach and lecture on Zen. In the last fifteen years of his life, he also wrote prolifically, striving to preserve his teachings and experiences for future generations. Much of his writing was in the vernacular and popular poetic forms, making it widely accessible to the literate public. Through these efforts, Hakuin significantly broadened the reach of Zen, ensuring it was no longer confined solely to the monastic elite but open to anyone earnest in spirit.

Teaching style and writings

Hakuin’s teaching style was direct, lively, and often colorful. He made extensive use of humor, vivid metaphors, and even deliberate provocations to jolt students out of complacency. His written works, including “Wild Ivy” and “Precious Mirror Cave”, combine sharp insight with practical instruction. He also produced numerous calligraphic works and paintings, integrating Zen spirit with artistic expression.

Through his energetic teaching, innovative methods, and outreach to the broader society, Hakuin Ekaku revitalized Japanese Rinzai Zen, leaving a living legacy that continues to inspire practitioners today.

Calligraphy

An important element of Hakuin’s Zen teaching and pedagogy was his painting and calligraphy. He seriously took up painting only late in life, at almost age sixty, but is recognized today as one of the greatest Japanese Zen painters. His artworks were not created for aesthetic purposes alone; they were intended as “visual sermons”, expressing core Zen values in forms accessible to a wide audience.

Hakuin’s paintings and calligraphy captured the spirit of Zen with bold, expressive brushwork and simple, yet profound imagery. They were especially popular among laypeople, many of whom were illiterate, providing an immediate, non-verbal encounter with Zen teachings. His portrayals of figures like Bodhidharma, humorous monks, and symbolic motifs conveyed essential lessons about awakening, perseverance, and the folly of attachment.

Today, paintings of Bodhidharma by Hakuin Ekaku are highly sought after and displayed in leading museums around the world, standing as enduring testaments to his ability to communicate Zen’s transformative insights through visual art.

Conclusion

Hakuin Ekaku stands out as one of the most influential figures in the history of Japanese Zen. Through his revitalization of Rinzai Zen, he reestablished rigorous practice as the foundation of the tradition at a time when it had lapsed into formalism and passivity. His insistence on integrating awakening into everyday life, his reorganization of kōan practice, his critique of “do-nothing Zen”, and his outreach to laypeople all served to make Zen a living, dynamic tradition accessible beyond the confines of monastic communities. Hakuin’s emphasis on post-satori training, the cultivation of bodhicitta, and the need for continuous exertion defined his mature teaching and left an enduring legacy in the structure of modern Rinzai training. His commitment to physical vitality as a component of practice and his creative use of painting and calligraphy as tools for instruction further demonstrate his comprehensive approach to spiritual life.

When we compare Hakuin to earlier discussed Bankei, we can see a clear contrast. Both masters rejected the idea that awakening was the privilege of the few and emphasized that it is directly accessible in this life. However, their methods and emphases diverged sharply. Bankei stressed the inherent presence of the unborn Buddha-Mind, teaching that realization arises naturally when interference ceases. His approach was radically immediate, largely rejecting formalized methods, intensive discipline, or staged practice. Awakening for Bankei was a matter of recognition, not effort.

In contrast, Hakuin viewed initial awakening as only the beginning of the path. He emphasized that without continuous and severe training, including intensive kōan practice and vigorous post-satori cultivation, initial insights would wither into complacency. Where Bankei warned against manufacturing artificial doubt and suffering through rigid methods, Hakuin believed that Great Doubt, and the psychological pressure it generated, was essential for breaking through self-centered delusions. Hakuin thus reintegrated structured discipline, doctrinal study, and personal struggle into the path of Zen, seeking not just naturalness, but forged and embodied realization.

These differences reflect broader currents within Zen itself. Bankei represented an existential immediacy rooted in trust in the original mind, while Hakuin, drawing on both traditional rigor and new innovations, reasserted disciplined training as the heart of the Rinzai tradition. Both offered vital correctives against spiritual stagnation in their times. Yet in the long view, it was Hakuin’s model, with its systematic method, psychological sophistication, and focus on post-awakening practice, that had the more lasting institutional influence on the shape of Japanese Rinzai Zen.

In sum, Hakuin Ekaku redefined Zen practice for subsequent generations, preserving its existential urgency while reinforcing its demand for disciplined transformation. His life and work remain key reference points for understanding both the challenges and the possibilities of awakening in the midst of human life.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments