The Arhat: The ideal of liberation in early Buddhism

In the early Buddhist tradition, the figure of the Arhat (Pāli: Arahant) stands as the ideal of complete liberation. The term literally means “worthy” or “one who is deserving of offerings”, but more profoundly, it signifies the person who has eliminated all defilements (kilesa) and reached the cessation of suffering — nirvana. Unlike later Mahāyāna conceptions of spiritual attainment, which often idealize the Bodhisattva who forgoes nirvana to aid all beings, the Arhat is one who has completed the path. In this post, we explore the Arhat not only as a doctrinal figure, but also as a psychological, ethical, and mythological symbol within the broader fabric of Buddhist thought.

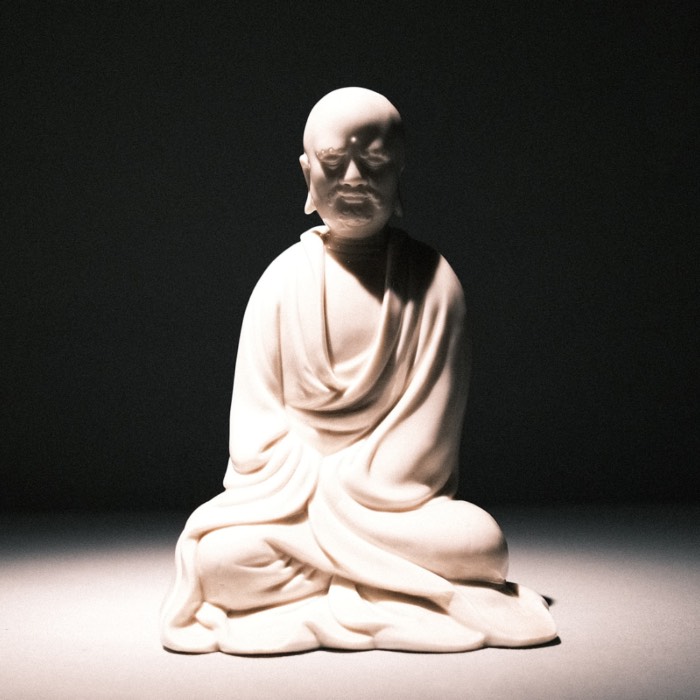

Statue of a Arhat, found at Yixian, Hebei province, China, Liao dynasty (907–1125). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC 1.0)

The Arhat in early Buddhist doctrine

In the canonical discourses of the Nikāyas and Āgamas, the Arhat is portrayed as the individual who has brought the entire structure of suffering to a complete end. They are said to have fully realized the Four Noble Truths, extinguished craving (tanhā), and broken the chain of dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda) at every link. This transformation is not partial or temporary; it is absolute and irreversible. Whereas the ordinary person (puthujjana) remains caught in the perpetual orbit of ignorance, craving, and rebirth, and the stream-enterer (sotāpanna) has only broken the first fetters, the Arhat has crossed the river entirely. There is no return to delusion, no relapse into grasping, and no further becoming. Their liberation is final, complete, and unshakeable.

The Arhat’s mind is described as unassailable, calm, and immovable, beyond the reach of desire, aversion, or confusion. Central to this transformation is the complete eradication of the kilesas, the mental defilements that sustain suffering. These are typically classified as greed (lobha), hatred (dosa), and delusion (moha), but also include subtle distortions such as conceit, restlessness, and doubt. In the unenlightened mind, the kilesas drive volitional action and bind consciousness to the karmic cycle. The Arhat, by contrast, has cut through these distortions at the root. The destruction of the kilesas is what makes the Arhat’s liberation irreversible: there is no longer any basis for craving, aversion, or confusion to reemerge.

They have not merely understood the teachings, but directly penetrated the nature of all conditioned phenomena: impermanent, unsatisfactory, and devoid of self. What is destroyed is not the world or the body, but the illusion that there is a “self” to whom experience belongs. This insight dissolves the basic framework through which most people experience existence. Having seen this truth, the Arhat continues to live in the world, but does so without clinging, without resistance, and without constructing identity. They walk among others, but are no longer psychologically entangled in the world’s projections.

The Arhat as a mythological and narrative figure

While the Arhat represents a philosophical ideal, Buddhist tradition also presents Arhats as living, sometimes miraculous figures. The Pali Canon abounds with stories of historical Arhats such as Sāriputta, Mahā Moggallāna, and Mahā Kassapa, who not only embody deep wisdom but also perform feats of supernormal knowledge and meditative prowess.

In later traditions, especially in Chinese and Tibetan Buddhism, the Arhat becomes further mythologized. The eighteen Arhats (or Luohan) are revered as semi-divine protectors of the Dharma. Their images adorn temples, each embodying unique postures and expressions, symbolizing different aspects of the spiritual path. This shift from human exemplar to guardian figure reflects how the Arhat ideal evolved to meet devotional and narrative needs, while still anchoring the tradition in the promise of liberation.

Psychological and existential transformation

In Buddhist thought, the person described as an Arhat does not escape the world in a metaphysical or supernatural sense. Rather, they undergo a profound transformation in the way reality is perceived and experienced. The sensory world remains intact: sights, sounds, thoughts, and bodily sensations still occur. What changes is not the content of experience, but its structural interpretation. Ordinarily, there is an almost automatic assumption that each sensation or thought belongs to a stable, inner “I”, that experiences happen to someone, that I feel pain, joy, loss, or pride. From a Buddhist perspective, this is a fundamental misperception.

The Arhat sees through this illusion. They no longer perceive experience as something occurring to a self, but as a dynamic stream of conditioned processes, bodily sensations, mental formations, perceptions, and reactions, all arising and passing away without a core or owner behind them. This insight dissolves the habitual tendency to grasp or resist what arises, because there is no longer a self to protect, defend, or preserve. Suffering, which in Buddhist analysis arises from this very reactivity and identification, ceases at the root.

This transformation does not stem from emotional suppression or withdrawn detachment. It is grounded in direct insight into the nature of reality as a flux of interdependent phenomena. What is commonly taken to be a stable, enduring self, a central agent behind thoughts, feelings, and intentions, is revealed to be a mental construction, a product of habit and ignorance. The Arhat sees clearly that experience unfolds moment by moment as conditioned events: sensations, feelings, perceptions, and mental reactions that arise and vanish without continuity, control, or ownership.

Because the illusion of an inner controller has been dispelled, the psychological mechanisms that generate craving and aversion lose their foundation. The Arhat no longer seeks to acquire what is pleasant or avoid what is unpleasant, for there is no “I” to benefit or suffer. Feelings still arise, but they are no longer personalized. They do not provoke the habitual loops of reaction, resistance, or narrative construction. In this liberated state, even intense experiences pass through awareness like weather through an open sky, noticed, but ungrasped.

In this way, the Arhat lives in the same world as everyone else, but encounters it with unclouded clarity. Their experience is not numbed or disengaged, but deeply free. There is awareness, contact, and even responsiveness, but without the compulsive overlay of self-referencing. What remains is a steady, grounded presence that meets the world as it is, not as it is feared or desired to be.

Two-phase liberation: Nirvana in life and after death

From a Buddhist soteriological perspective, the liberation of the Arhat is not limited to a single moment of awakening, but unfolds in two phases that mark distinct aspects of their freedom from suffering and rebirth. Early Buddhist texts clearly distinguish between these two phases. While alive, the Arhat attains saupādisesa-nibbāna, i.e., nirvana “with remainder”. This means that although the Arhat is fully liberated and no longer generates new karma, they still exist within the conditions shaped by previous actions: a body that ages, a mind that experiences sensations, and a world that continues to present causes and effects. In Buddhist thought, karma refers to intentional actions that shape the conditions of future experience. These actions leave imprints that influence rebirth and perpetuate suffering as long as they are motivated by ignorance, desire, or aversion. In other words, karma is not simply “moral debt,” but the very engine that keeps the cycle of rebirth (samsāra) turning.

What prevents the generation of new karma in the case of the Arhat is not physical withdrawal or passive restraint, but the complete absence of the mental defilements that give rise to karmic momentum. In Buddhist theory, karma arises from volitional intention (cetana) rooted in unwholesome states such as greed, hatred, and delusion. Because the Arhat has eradicated these tendencies at the root, their actions are no longer stained by clinging or aversion. They may still act like speak, walk, eat, or teach, but these actions flow from clarity and equanimity. They do not give rise to future becoming, because there is no self-referential impulse left to sustain further birth.

In this phase, the five aggregates (skandhas), form, sensation, perception, mental formations, and consciousness, continue to function as part of the natural unfolding of prior conditions. But they are no longer appropriated as “mine” or “me.”

Upon physical death, these residual conditions fall away as well. This final transition is known as anupādisesa-nibbāna, nirvana “without remainder”. It marks the end of even the lingering consequences of past karma. There is no rebirth, no further arising of mental or physical processes. Importantly, this is not annihilation, because there was never an essential self to annihilate. What ceases is not a person or soul, but the dynamic illusion of selfhood, which has already been undermined during life.

To understand this cessation, it helps to consider the Buddhist theory of causality. Each moment of experience arises based on preceding conditions. Like a series of billiard balls set in motion, one action propels the next: a thought leads to speech, a desire leads to action, a reaction triggers another response. In the cycle of samsāra, this momentum is fueled by karmic intention. The volitional act is like the first ball hitting the next, but with the added twist that the action is embedded in confusion, especially the idea that “I” am the one acting, gaining, losing, or being threatened. It is this self-referential quality that gives karma its potency and its binding effect. In fact, it is precisely karmic action, i.e., intention rooted in craving (tanhā) and delusion (avijjā), that constructs and reinforces the illusion of a constant, substantial “I”. Each act motivated by clinging or resistance perpetuates the mistaken sense of selfhood, because it frames experience as something happening to someone. In this way, karma and the illusion of self sustain one another in a mutually reinforcing loop. And the Arhat is liberated from both.

When an Arhat acts, they may still move the billiard ball. But without the illusion of a self behind the motion. There is no desire for outcome, no aversion to result, no imagined self that needs to persist. The ball moves, but it doesn’t set the next one into motion with karmic force. Why? Because there’s no longer a deluded framework tying the act to a future state of becoming. Just as a gust of wind may move a ball without generating a karmic link, so the Arhat’s actions, while intentional, are no longer entangled in reactivity or appropriation.

The Arhat’s death is thus likened in the texts to the extinguishing of a flame that, having run out of fuel, simply goes out, not into something else, but into non-conditionality itself. This analogy helps clarify that nirvana, even in its final form, is not a void or negation, but the cessation of illusion and the complete unraveling of conditioned existence.

The karma–self loop

How karma and the illusion of self reinforce each other in Buddhist thought:

Intentional action (karma) arises from ignorance (avijjā), craving (tanhā), and aversion (dosa). These actions are typically motivated by the assumption of a stable “I”: I want, I fear, I act. Each karmic act further reinforces the illusion of this “I”, because experience is interpreted as happening to me. This feedback loop creates momentum that conditions future mental and physical states, including rebirth. As long as craving and delusion persist, the cycle of

karma → self → karma → self

perpetuates. The Arhat breaks this loop: they act without appropriation, without “I-making”, and without craving. As a result, their actions do not generate new karma, and the illusion of self dissolves completely.

Ethical implications: Spontaneous virtue

With the end of craving and self-centered thinking, the Arhat naturally embodies the brahmavihāras, loving-kindness (mettā), compassion (karuṇā), sympathetic joy (muditā), and equanimity (upekkhā). These states are not developed through effort or ethical striving, but arise as spontaneous expressions of a mind no longer distorted by grasping or aversion. Because the illusion of a separate, enduring self has been dismantled, the boundaries between self and other lose their compelling force. The Arhat does not need to cultivate empathy in the usual sense, empathy is simply what remains when the barrier of ego has fallen.

The Arhat’s actions are ethically impeccable not because they adhere to rules, but because their motivations are unclouded. Their conduct flows from insight rather than ideology. Compassion is not sentimental, reactive, or dependent on identity; it arises from unobstructed clarity. The Arhat sees suffering without filtering it through the question of whether it is their own or someone else’s, and responds with equanimity and care. Ethics, for the Arhat, is not imposed but revealed through the transparency of awakened perception.

Mahāyāna reinterpretation and critique

Later Mahāyāna texts criticize the Arhat ideal as incomplete or self-centered. In these accounts, the Arhat is portrayed as someone who seeks personal liberation for themselves, in contrast to the Bodhisattva, who takes a vow to liberate all beings before seeking final awakening. Some Mahāyāna schools go so far as to reinterpret Arhatship as a preliminary or limited attainment: one that must ultimately give way to the higher realization of full Buddhahood.

However, this critique must be understood in its historical and rhetorical context. Early texts do not present Arhats as emotionally cold, socially disengaged, or ethically passive. On the contrary, their equanimity and insight are held up as exemplary, and their liberation is portrayed as the end of self-centeredness, not its triumph. The Mahāyāna critique may reflect a shift in emphasis from individual liberation to universal compassion, rather than a refutation of the Arhat ideal itself. As such, the contrast between Arhat and Bodhisattva is best seen not as a contradiction, but as a broadening of spiritual perspective. One that reimagines the scope and aim of awakening, without necessarily negating the foundational realization the Arhat represents.

Conclusion

The Arhat, as conceived in early Buddhist tradition, represents the culmination of the Buddhist path: not as a supernatural being or heroic savior, but as a human who has fully awakened to the impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and selflessness of all conditioned phenomena. Their liberation is grounded in the direct, irreversible realization that the sense of self is an illusion maintained by craving (tanhā), aversion (dosa), and ignorance (avijjā). A realization that fundamentally alters their way of perceiving and interacting with the world.

The Arhat stands as the living embodiment of the Buddhist path’s deepest promises. Doctrinally, they are the one who has dismantled the karmic engine by uprooting greed, hatred, and delusion. Psychologically, they no longer respond to the world from an imagined center of self, but encounter reality with a clarity unburdened by reactivity. Their actions flow from non-appropriated presence, not compelled by desire or aversion, but guided by awareness. Mythologically, they traverse the full arc of Buddhist storytelling: from historical disciples who realized nirvana to figures venerated in East Asian temples as protectors of the Dharma. And ethically, the Arhat manifests compassion (karuṇā) and equanimity (upekkhā) not through moral striving, but through the absence of the egoic habits that distort perception and response – thus, as spontaneous expressions of a mind no longer caught in the web of self-referentiality. Their life is not morally exemplary because they follow rules, but because there is nothing left in them to violate integrity.

The figure of the Arhat has been subject to debate, particularly in later Mahāyāna traditions that reframed the ideal as self-limiting when compared to the Bodhisattva. However, such critiques often reflect differing soteriological emphases rather than outright contradictions. Far from being self-centered, the Arhat’s liberation marks the end of egocentric perspective and the beginning of unconditioned responsiveness to the world.

In sum, the Arhat is not one who escapes the world, but one who sees through its illusions. Their life illustrates the core insight of Buddhist philosophy: that freedom does not require withdrawal from experience, but awakening within it.

I hope this account has helped clarify the image of the Arhat and dispel common misconceptions, especially those that arise when viewed solely through the lens of later Mahāyāna reinterpretations. Rather than a figure of self-centered retreat, the Arhat represents the radical dissolution of self-centeredness altogether and, thus, fully incorporates the ethical and compassionate dimensions of the Buddhist path.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments