Bodhicitta: The heart of awakening

Bodhicitta, often translated as “awakening mind” or “mind of enlightenment”, is the foundational intention and commitment that defines the Bodhisattva path in Mahāyāna Buddhism. More than a thought or emotion, bodhicitta is a profound shift in orientation: the wish to attain full awakening not for oneself alone, but for the liberation of all sentient beings. In this post, we explore the meaning, development, and significance of bodhicitta, both in traditional Buddhist frameworks and in contemporary ethical practice.

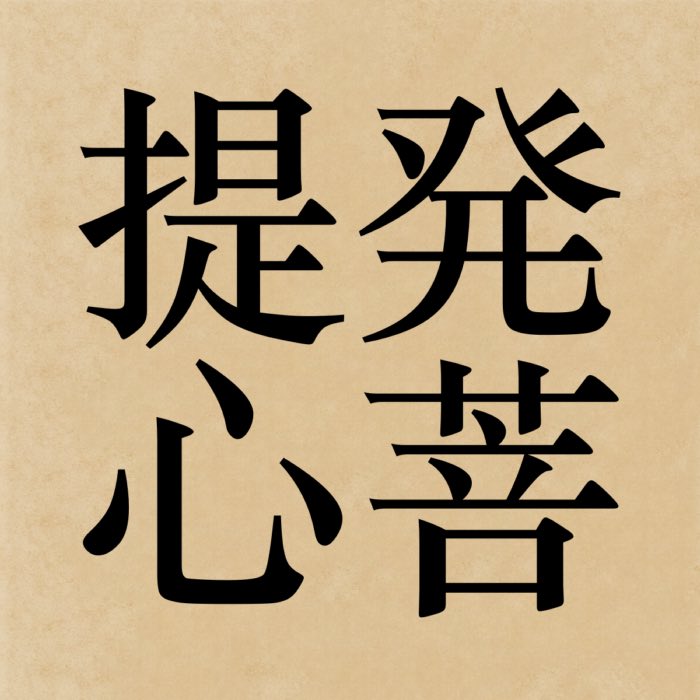

Gandharan relief depicting the ascetic Megha (Shakyamuni in a past life) prostrating before the past Buddha Dīpaṅkara and vowing to become a Buddha, c. 2nd century CE, Gandhara, Swat Valley, today Pakistan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC 1.0)

Etymology and meaning

The Sanskrit term bodhicitta combines bodhi (awakening, enlightenment) and citta (mind, heart, or intention). Together, they form a concept that goes beyond mere aspiration: bodhicitta is the internal turning toward awakening as a shared project, rooted in the felt interconnection with all sentient life. It signifies not only a goal (enlightenment) but a fundamental redirection of the practitioner’s mind and life-purpose. Rather than seeking liberation solely from personal suffering, bodhicitta expresses the resolve to attain awakening precisely so that others may be freed. In this way, it reorients the entire path of practice from inward escape to outward responsibility.

Relative and ultimate bodhicitta

Traditional Mahāyāna teachings distinguish between two intimately connected dimensions of bodhicitta: relative and ultimate.

Relative bodhicitta is the conscious intention to attain awakening out of compassion for all beings. It manifests as an ethical resolve to engage with the world and help others overcome suffering, not out of obligation, but from a profound sense of shared vulnerability and kinship. This aspect of bodhicitta guides moral conduct, social action, and the cultivation of qualities such as patience, generosity, and loving-kindness. It provides the emotional and volitional basis for the Bodhisattva’s vow.

Ultimate bodhicitta, on the other hand, is the non-conceptual realization of emptiness (śūnyatā), the insight that all phenomena, including the self, others, and even compassion itself, lack inherent existence and arise interdependently. This is not mere intellectual understanding, but a radical shift in perception that dissolves self-other duality at its root. From this view, there is no separate being to save and no agent to perform the saving; compassionate activity becomes spontaneous, unobstructed, and free from attachment.

Far from being separate or sequential, these two dimensions support and deepen one another. Relative bodhicitta provides the motivation and practical expression of care; ultimate bodhicitta liberates that care from grasping and delusion. The path of the Bodhisattva unfolds as a dynamic interplay between these two: compassion without clinging, and wisdom without withdrawal.

Cultivation and practice

Bodhicitta is not presumed to arise on its own through passive understanding or time. Instead, it must be deliberately cultivated through specific contemplative and affective practices. One foundational method emphasized in classical texts is the cultivation of the Four Immeasurables (brahmavihāras): loving-kindness (mettā), compassion (karuṇā), empathetic joy (muditā), and equanimity (upekkhā). These four attitudes establish the emotional basis for bodhicitta by softening self-centeredness and expanding one’s concern to all sentient beings without exception.

A more elaborate approach, often attributed to Atiśa and the Kadampa tradition, is the sevenfold cause-and-effect method. This sequence begins with recognizing all beings as having once been one’s mother in past lives, recalling their kindness, and developing a sense of gratitude. This reflection matures into the wish to repay their kindness through spiritual liberation, culminating in the generation of genuine bodhicitta. This technique draws on affective memory and emotional logic to generate an altruistic resolve that transcends mere empathy.

Another pivotal method, especially in Tibetan traditions, is the practice of exchanging self and other. Here, the practitioner works to undermine the habitual prioritization of their own well-being over that of others. Practices like tonglen (“sending and receiving”) concretely enact this exchange: one breathes in the suffering of others and breathes out relief, love, and healing. These imaginative exercises train the practitioner to identify with others’ pain and decenter their own egoic interests. Over time, this fosters an embodied compassion that is not limited by identity or attachment.

Taken together, these methods cultivate the emotional depth, cognitive clarity, and ethical resolve that allow bodhicitta to take root and mature. They are not devotional ornaments or optional supplements, but the structured means through which the practitioner actively reshapes their perception, intention, and being in the world.

Developmental stages

Some traditions outline a progressive deepening of bodhicitta:

- Aspired bodhicitta: the sincere wish to awaken for others.

- Engaged bodhicitta: the active undertaking of the Bodhisattva vows and pāramitā practices.

These two levels represent distinct but interwoven stages in the cultivation of bodhicitta. Aspired bodhicitta marks the initial cognitive and emotional shift: a recognition of universal suffering and a heartfelt resolve to respond. It involves the generation of intent and is grounded in moral imagination and affective empathy. However, at this stage, the practitioner has not yet committed to action in the world. Engaged bodhicitta, by contrast, denotes a decisive turning point: the practitioner now assumes responsibility, formally embraces the Bodhisattva vows, and begins to integrate wisdom and compassion through disciplined training in the six pāramitās. This progression reflects both an inner psychological transformation — the overcoming of self-centered habituation — and an outer ethical commitment — the entry into a life of deliberate, selfless service to others.

Philosophical dimensions

In the Madhyamaka school, bodhicitta is not a constructed ethical intention layered onto insight but the spontaneous expression of a mind that has fully realized the emptiness (śūnyatā) of all phenomena. Here, wisdom and compassion are not separate faculties: the direct perception of the lack of intrinsic identity in self and others gives rise to a compassion unbound by subject-object duality. From this standpoint, bodhicitta is the natural energetic outflow of realizing that all beings suffer due to their clinging to illusory selves.

In the Yogācāra tradition, bodhicitta is rooted in the purification of consciousness itself. It emerges when dualistic subject-object cognition is transformed into non-dual awareness through the progressive refinement of mental processes. This transformation allows the practitioner to overcome the habitual bifurcation between self and other, leading to a compassionate impulse that no longer arises from volitional effort but from a deep restructuring of perception.

Zen and Chán traditions, particularly influenced by the Chinese synthesis of Madhyamaka and Yogācāra, go a step further in dissolving even the notion of bodhicitta as a distinct attainment. In these lineages, bodhicitta is not a goal to be cultivated, attained, or achieved; it is the very expression of non-separation that underlies all reality. In this view, to practice bodhicitta is simply to realize and embody the groundless ground of being, a spontaneous, formless compassion that requires no justification and recognizes no boundary between the sacred and the ordinary.

Contemporary relevance

Bodhicitta offers a transformative framework for altruistic engagement that circumvents both moralism, the rigid imposition of duty, and self-denial (the suppression of personal integrity or well-being). Its strength lies in the fact that it is not grounded in externally imposed commandments, but in the direct experiential insight into interdependence. In this sense, bodhicitta does not demand action for the sake of an abstract ideal, but allows action to emerge from a radical shift in perspective: from self-reference to co-existence, from ownership to mutuality. In facing today’s crises, e.g., ecological collapse, structural injustice, and spiritual disorientation, bodhicitta reframes ethical life as an expression of clarity rather than effort, of intimacy rather than identity. It does not ask us to renounce the world, but to enter it more fully and consciously, as participants in a shared condition whose liberation is inseparable from our own.

Conclusion

Bodhicitta is both the foundational motivation and the enduring structure of the Bodhisattva path. It is not a static principle but a dynamic orientation that guides the practitioner from initial aspiration to advanced realization. Bodhicitta bridges ethical intention and philosophical insight: it begins as a volitional commitment to act for the benefit of others and deepens into a non-dual awareness that renders the distinction between self and other obsolete. The relative and ultimate dimensions of bodhicitta, compassionate resolve and insight into emptiness, are not opposed poles but dynamically co-dependent aspects of awakening. Compassion without wisdom risks becoming sentimental or possessive; wisdom without compassion risks retreating into detachment. Bodhicitta sustains their union. It transforms the practitioner’s path from linear progress toward a goal into a circular, responsive, and open-ended movement: insight gives rise to compassionate action, which deepens insight again. This reflexivity, grounded in interdependence, is what allows bodhicitta to remain vital and non-dogmatic across time, culture, and tradition.

Various schools of Mahāyāna thought articulate this dynamic in distinct ways: Madhyamaka sees bodhicitta as the natural expression of emptiness-realization, Yogācāra emphasizes the transformation of consciousness into non-dual awareness, and Chán/Zen traditions embody bodhicitta as the spontaneous presence of awakened life. Despite these differences, all converge on the view that bodhicitta is not merely a virtuous attitude but a structural reorientation of the entire mind. It transcends self-centered motivation without demanding its suppression, and enacts altruistic responsiveness without falling into moralism.

Bodhicitta’s strength lies in its capacity to resist reification. It is not an identity, a doctrine, or a fixed stage of development, but an ongoing process of de-centering and attunement. As such, it offers an alternative to both secular ethical systems grounded in autonomy and traditional religious systems based on obedience. Bodhicitta does not enforce ethical norms from the outside, but allows compassionate action to arise organically from the recognition of interdependence. In this way, it provides a relevant and resilient model for engaging with the suffering of the world, one that is grounded, flexible, and deeply human.

In sum, bodhicitta is not merely the beginning of the Bodhisattva path; it is the shape and rhythm of its unfolding. It is the intention that transforms into insight, and the insight that returns as compassionate action. As long as suffering persists, bodhicitta remains the criterion and expression of authentic awakening.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments