Tibetan monastic sites: Samye, Sakya, and the foundations of institutional Buddhism in Tibet

The emergence of monastic institutions in Tibet between the 8th and 13th centuries marked a foundational period in the formation of Tibetan Buddhism as a system of doctrinal transmission, ritual authority, and scholastic discipline. While early Tibetan kings had introduced elements of Indian Buddhism into the court and elite circles, it was through the establishment of permanent monastic centers, beginning with Samye and followed by others such as Sakya, that a sustained institutional framework for Buddhism was created.

Central building of the Samye Monastery, Tibet. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Central building of the Samye Monastery, Tibet. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

This formative era unfolded against a backdrop of dramatic political and religious transformation. During the height of the Tibetan Empire under rulers such as Trisong Detsen, royal patronage supported the translation of Indian texts, the invitation of Buddhist scholars, and the suppression of indigenous ritual specialists who resisted Buddhist norms. However, following the fragmentation of imperial authority in the 9th century, Buddhism in Tibet experienced a period of decentralization, followed by a remarkable revival known as the “Second Diffusion” (phyi dar), which saw the re-establishment of ordination lineages, scholastic reform, and the emergence of powerful new schools.

In this post, we examine two of the most emblematic monastic institutions of this era — Samye and Sakya — focusing on their founding, doctrinal orientations, architectural innovations, and political entanglements. We also investigate the broader significance of these sites within the evolving network of Tibetan monasticism and their lasting contributions to Buddhist institutional culture across Inner Asia.

Historical background

The Tibetan empire and Buddhist introduction

The formal introduction of Buddhism into Tibet occurred during the reign of Trisong Detsen (r. ca. 755–797), a period marked by strong imperial centralization and an outward-looking cultural policy. Recognizing the potential of Buddhist doctrine and monastic discipline to bolster political authority and cultural prestige, Trisong Detsen actively invited Indian scholars such as Śāntarakṣita and Padmasambhava to Tibet. Śāntarakṣita is credited with establishing the first ordination lineage and initiating the translation of Buddhist scriptures into Tibetan, while Padmasambhava played a key role in adapting tantric practices to the Tibetan environment and in overcoming resistance from indigenous ritual specialists (bön and other non-Buddhist traditions).

Royal patronage during this period led to the construction of Samye Monastery, the first fully institutionalized Buddhist monastery in Tibet, which symbolized the integration of Indian scholastic models with Tibetan political ambition. Despite official support, the promotion of Buddhism often encountered resistance from entrenched aristocratic and priestly groups, who viewed the new religion as a threat to traditional cosmologies and power structures. This tension would continue to shape Tibetan religious development for centuries.

Fragmentation and renaissance

The collapse of centralized authority following the assassination of Langdarma in the mid-9th century ushered in a period of political disintegration and religious decline. Known as the “Era of Fragmentation” (sil bu’i dus), this time saw the dissolution of the imperial court and the interruption of monastic ordination lineages. Buddhism survived primarily in localized communities and through lay transmission of ritual texts and practices.

However, from the late 10th century onward, Tibet experienced a Buddhist revival commonly referred to as the “Second Diffusion” (phyi dar). This renaissance was driven by renewed contact with Indian centers of learning, particularly through translators such as Rinchen Zangpo, and by the establishment of new monastic centers in western and central Tibet. The reintroduction of ordination, the systematization of translation, and the development of distinct doctrinal lineages, including the Kadam, Sakya, and early Kagyu schools, restored Buddhism as a dominant cultural and institutional force across the plateau.

Samye monastery

The Samye Monastery (Tibetan: བསམ་ཡས་དགོན་པ་, bsam yas dgon pa), located in the Yarlung Valley of central Tibet, is widely recognized as the first monastery established in Tibet. It was founded in the late 8th century and served as a model for subsequent monastic institutions. Samye’s significance lies not only in its architectural grandeur but also in its role as a center for doctrinal transmission, translation, and the establishment of monastic ordination lineages.

Samye, photographed in 1936 by Hugh Edward Richardson. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Founding and design

Samye Monastery, constructed in the late 8th century under the patronage of King Trisong Detsen, stands as the first fully institutionalized Buddhist monastery in Tibet. Its establishment followed the arrival of Śāntarakṣita, an Indian monk-philosopher from Nālandā, who advocated the introduction of a formal monastic ordination system. Due to initial resistance from indigenous ritual specialists, Śāntarakṣita recommended inviting Padmasambhava, a tantric adept, to overcome spiritual obstacles and facilitate the monastery’s construction.

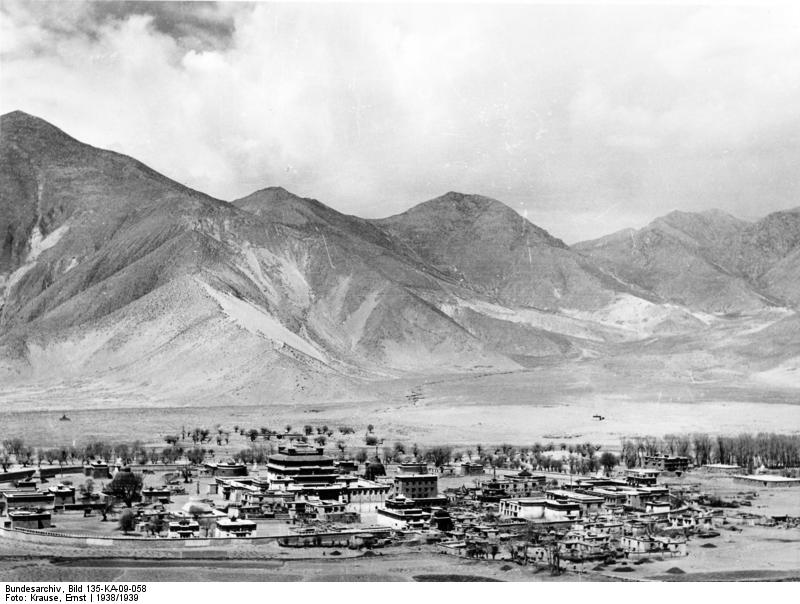

Samye 1939. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

The design of Samye was heavily symbolic and cosmological. It was modeled after the Odantapuri and Nālandā monasteries in India but also incorporated Chinese architectural elements, reflecting the confluence of trans-Himalayan Buddhist influences. The monastery’s layout was based on a mandala, with the central temple representing Mount Meru, the cosmic axis of Buddhist cosmology, and smaller temples surrounding it representing the continents. This spatial symbolism asserted the monastery’s role not only as a scholastic institution but also as a microcosmic representation of the Buddhist universe.

Doctrinal and ritual role

Samye was the site of pivotal doctrinal events that helped define the trajectory of Tibetan Buddhism. Most notably, it hosted the famous “Council of Samye” or “Debate of Samye” in the late 8th century, where Chinese Chán (Zen) teachings and Indian gradualist approaches to enlightenment were debated. The Indian side, represented by Kamalaśīla, was declared the victor, and this event laid the groundwork for the dominance of Indian scholastic methods and textual authority in Tibetan monasticism.

The monastery became a principal center for translation work, hosting teams of Indian and Tibetan scholars who rendered a vast body of Buddhist scriptures into Tibetan. Samye was instrumental in establishing the ordination lineage that would define Tibetan monastic life and thus played a crucial role in legitimizing the institutional saṅgha. Over time, it became closely associated with the Nyingma school, the oldest of the Tibetan Buddhist traditions, though its legacy extended far beyond any one lineage.

Samye’s architectural grandeur, doctrinal importance, and foundational role in Tibetan monasticism made it a template for later institutions and a powerful symbol of the formal integration of Buddhism into Tibetan statecraft and cultural identity.

Sakya monastery

The Sakya Monastery (Tibetan: ས་སྐྱ་, sa skya), located in the Sakya region of Tibet, emerged as a significant center of Buddhist learning and practice during the 11th century. It is one of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism and is particularly known for its emphasis on the Lamdré (Path and Result) teachings, which integrate philosophical study with tantric practice.

Sakya monastery, Tibet. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Foundation and early growth

Sakya Monastery was founded in 1073 by Khön Könchok Gyalpo, a member of the aristocratic Khön family who played a crucial role in the religious renaissance of central Tibet during the Second Diffusion of Buddhism. The Khön lineage traced its heritage back to imperial Tibet and combined political influence with emerging spiritual authority. The foundation of Sakya marked the institutionalization of a new doctrinal lineage grounded in tantric scholarship and monastic discipline.

Sakya founding fathers. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Central to Sakya’s doctrinal foundations was the transmission of advanced tantric teachings brought to Tibet by the translator Drokmi Lotsāwa. Having studied in Kashmir and other parts of India, Drokmi returned with key teachings, especially from the Lamdré system derived from the Indian master Virūpa. These teachings emphasized the integration of philosophical study with tantric yogic practice. Under the Sakya school, the Lamdré system became a central pillar of its scholastic and meditative curriculum. As the monastery grew, it developed an effective monastic administration and a reputation for scholastic excellence that would soon reach across Tibet and beyond.

Political and cultural significance

The Sakya school’s religious stature was amplified by its engagement with politics during the Mongol expansion into Central Asia. Sakya Paṇḍita (1182–1251), a renowned scholar and great-grandson of the monastery’s founder, was invited to the Mongol court. There, he formed a relationship with Prince Köden, which later paved the way for his nephew Phagpa (1235–1280) to establish an enduring alliance between the Sakya school and the Yuan dynasty.

Large assembly hall of the south monastery. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Phagpa was appointed imperial preceptor (Dishi) by Kublai Khan and became a key figure in codifying the priest-patron relationship (mchod yon), whereby the spiritual authority of the lama was exchanged for military protection and political recognition. This relationship marked a turning point in Tibetan history: the Sakya school governed Tibet under Mongol auspices for nearly a century, making Sakya Monastery the de facto administrative and religious center of Tibet during the 13th century.

Through this synthesis of religious scholarship and political leadership, Sakya Monastery exerted immense influence on both the cultural and institutional development of Tibetan Buddhism. Its model of centralized monastic authority, tantric integration, and scholastic rigor would go on to shape the future of Tibetan governance and religious identity.

Institutional and intellectual life

In the centuries following the establishment of Samye and Sakya, Tibetan monastic institutions evolved into complex centers of learning, ritual practice, and political engagement. The monastic landscape became increasingly diverse, with various schools and lineages emerging, each contributing to the rich tapestry of Tibetan Buddhism.

Monks at the Sakya monastery, Tibet. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Scriptural translation and scholarly activity

A hallmark of Tibetan monastic culture from the 8th through 13th centuries was the immense effort dedicated to the translation, preservation, and systematic study of Buddhist texts. Building upon the groundwork laid at Samye, later monasteries like Sakya became hubs of scholastic productivity. These efforts culminated in the creation of the bka’ ‘gyur (translated words of the Buddha) and bsTan ‘gyur (translated commentaries), monumental compilations that together constituted the Tibetan Buddhist canon. These collections reflect not only the volume of material translated from Sanskrit, Prakrit, and other languages but also the depth of Tibetan engagement with Indian scholastic traditions.

Sakya Monastery Library. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Monastic curricula during this period were rigorously structured, often spanning decades of study. Students progressed through debates, memorization, textual analysis, and formal examinations, typically focusing on logic (pramāṇa), Madhyamaka philosophy, Abhidharma, Vinaya, and Prajñāpāramitā literature. The institutionalization of scholastic training helped to unify doctrinal standards across regions and schools, fostering both intellectual continuity and the proliferation of doctrinal innovation.

Artistic and architectural developments

Tibetan monasteries developed a highly distinctive visual and spatial culture that blended indigenous motifs with imported artistic models. The influence of Indian, Kashmiri, and Newar artisans is evident in temple sculpture, bronze casting, and wall painting, especially in early sites such as Samye, and later in the elaborate murals of Sakya and its satellite institutions. These stylistic convergences gave rise to a hybrid aesthetic that would become characteristic of Tibetan religious art.

Inner yard of the Sakya monastery, Tibet. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Murals depicting Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, dharma protectors, and mandalas adorned temple interiors, serving both didactic and ritual purposes. Artistic production was closely integrated with meditative practice, especially in the case of tantric visualization rituals. Monastic libraries, meanwhile, housed meticulously copied manuscripts and printed texts, often stored in cloth-wrapped bundles and cataloged according to evolving classification systems.

Through these intellectual and artistic practices, Tibetan monastic institutions not only preserved and disseminated Buddhist knowledge but also gave it a uniquely Tibetan material and visual form.

Regional networks and legacy

The monastic institutions of Samye and Sakya were not isolated entities; they were part of a broader network of religious, cultural, and political interactions that shaped the development of Tibetan Buddhism. Their influence extended across the Tibetan plateau and into neighboring regions, creating a rich tapestry of monastic life that would endure for centuries.

Monastic expansion

The success and prestige of institutions like Samye and Sakya catalyzed a wide-reaching expansion of monastic networks across the Tibetan plateau. These monasteries served as archetypes for later foundations, many of which were established by traveling scholars, royal patrons, or ordained disciples aiming to replicate the liturgical, scholastic, and architectural standards of their parent institutions. As a result, regional hubs emerged, creating a dense and interconnected monastic geography that extended from the heartlands of Ü-Tsang to Amdo and Kham in eastern Tibet.

This expansion was not confined to intra-school growth. The Sakya school, in particular, maintained strong relations with other emerging schools such as the Kadampa and early Kagyu lineages. While doctrinal debates and competition were common, there was also significant cross-fertilization in ritual practices, scholastic methods, and institutional structures. Texts, teachers, and students circulated widely, producing a shared monastic culture grounded in mutual recognition of ordination standards and commentarial traditions.

Long-term influence

The legacy of Samye and Sakya extended far beyond the 13th century. Their institutional models and scholastic systems helped shape the later development of the Ganden Phodrang state under the Gelug school, founded by Tsongkhapa in the 15th century. The Gelug monastic order inherited and systematized many of the administrative practices, curriculum structures, and liturgical standards that had been pioneered during this earlier period.

Tibetan monasticism also spread outward into neighboring regions. In Central Asia, Mongolia, and the Himalayan borderlands (including Bhutan, Ladakh, and Sikkim), Tibetan-trained teachers established monasteries that replicated the architectural forms and scholastic disciplines of Tibetan prototypes. These institutions played a central role in shaping the religious identities of their respective communities and reinforced the transregional coherence of Tibetan Buddhism as a shared cultural and institutional framework.

Through this layered expansion and adaptation, the early monastic centers of Samye and Sakya laid the foundations for a distinctly Tibetan mode of Buddhism — textually rigorous, ritually elaborate, and institutionally durable.

Conclusion

The development of Tibetan monastic institutions between the 8th and 13th centuries marked a defining transformation in the religious, cultural, and political history of the Tibetan plateau. Monasteries such as Samye and Sakya did more than house monastics or preserve doctrine. They articulated new forms of religious authority, fostered intellectual rigor, and shaped the visual and ritual culture of Tibetan Buddhism in enduring ways.

Samye, as the first state-supported monastery, laid the architectural and institutional foundation for Buddhism’s integration into Tibetan political life. Its cosmological design and scholastic ambitions set the precedent for later monasteries. Sakya, by contrast, demonstrated how a religious institution could also function as a political entity, managing governance in partnership with external imperial forces. Together, these monasteries embodied complementary models of Tibetan monasticism: one rooted in royal patronage and scholastic lineage, the other in tantric transmission and political diplomacy.

The legacy of these early monasteries is profound. Their structures of curriculum, ordination, ritual, and administration were replicated across regions and generations. They catalyzed Tibet’s transformation into a major center of Buddhist learning, practice, and statecraft — whose influence extended across Inner Asia, the Himalayas, and into modern global Buddhism. Tibetan monasticism, as pioneered by Samye and Sakya, thus emerged not merely as a religious tradition but as a durable institutional and civilizational force.

References and further reading

- Davidson, Ronald M., Tibetan renaissance: Tantric Buddhism in the rebirth of Tibetan culture, 2008, Motilal Banarsidass Publications, ISBN: 978-8120832787

- Kapstein, Matthew, The Tibetan assimilation of Buddhism: Conversion, contestation, and memory, 2000, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195152272

- Tucci, Giuseppe, Tibetan painted scrolls, 2006, Art Media Resources, ISBN: 978-1878529398

- Petech, Luciano, Central Tibet and the Mongols: The Yüan-Sa-skya period of Tibetan history, 1990, Rome: Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, ISBN: 978-8863230727

- Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D., Tibet: A political history, 1967, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-8186230688

comments