Gandhāra: The Greco-Buddhist encounter and the birth of Buddhist figural art

Situated at the cultural crossroads of South Asia and the wider Hellenistic world, Gandhāra stands out as one of the most fascinating and consequential regions in ancient history. Over the course of nearly a millennium, it absorbed and synthesized influences from Persian, Greek, Indian, Central Asian, and Roman cultures, becoming a crucible of religious and artistic innovation. Nowhere is this synthesis more vividly expressed than in the development of Gandhāran Buddhist art: a tradition that redefined the visual language of Buddhism and shaped its transmission across Asia.

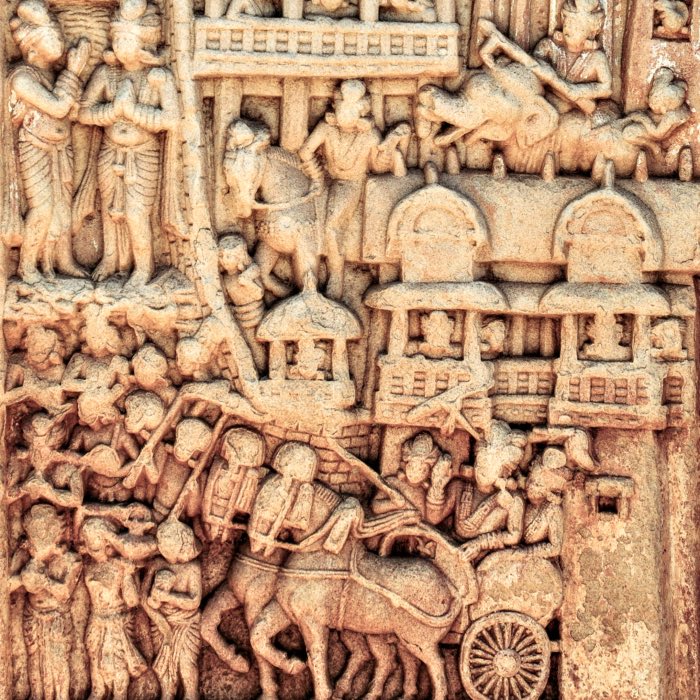

Panel from a relief series showing four scenes from the life of Siddhartha Gautama, here: enlightenment. Kushan dynasty, late 2nd to early 3rd century CE, Gandhara, schist. Reliefs like this one are characterized by their intricate details and the blending of Hellenistic and Indian artistic styles. The figures are depicted with naturalistic features, flowing drapery, and expressive gestures, reflecting the cultural syncretism that defined Gandhāran art. This particular relief is part of a larger narrative series that illustrates key events in the life of the Buddha, showcasing the region’s role as a center for Buddhist art and iconography. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC 1.0)

In this post, we explore the historical trajectory of Gandhāra, from its role in imperial networks to its golden age under the Kushans, and examine the unique art style that emerged from this multicultural milieu. Through a close look at archaeology, iconography, and cultural exchange, we aim to understand Gandhāra not only as a historical region but as a key chapter in the global history of Buddhist thought and artistic expression.

Historical background

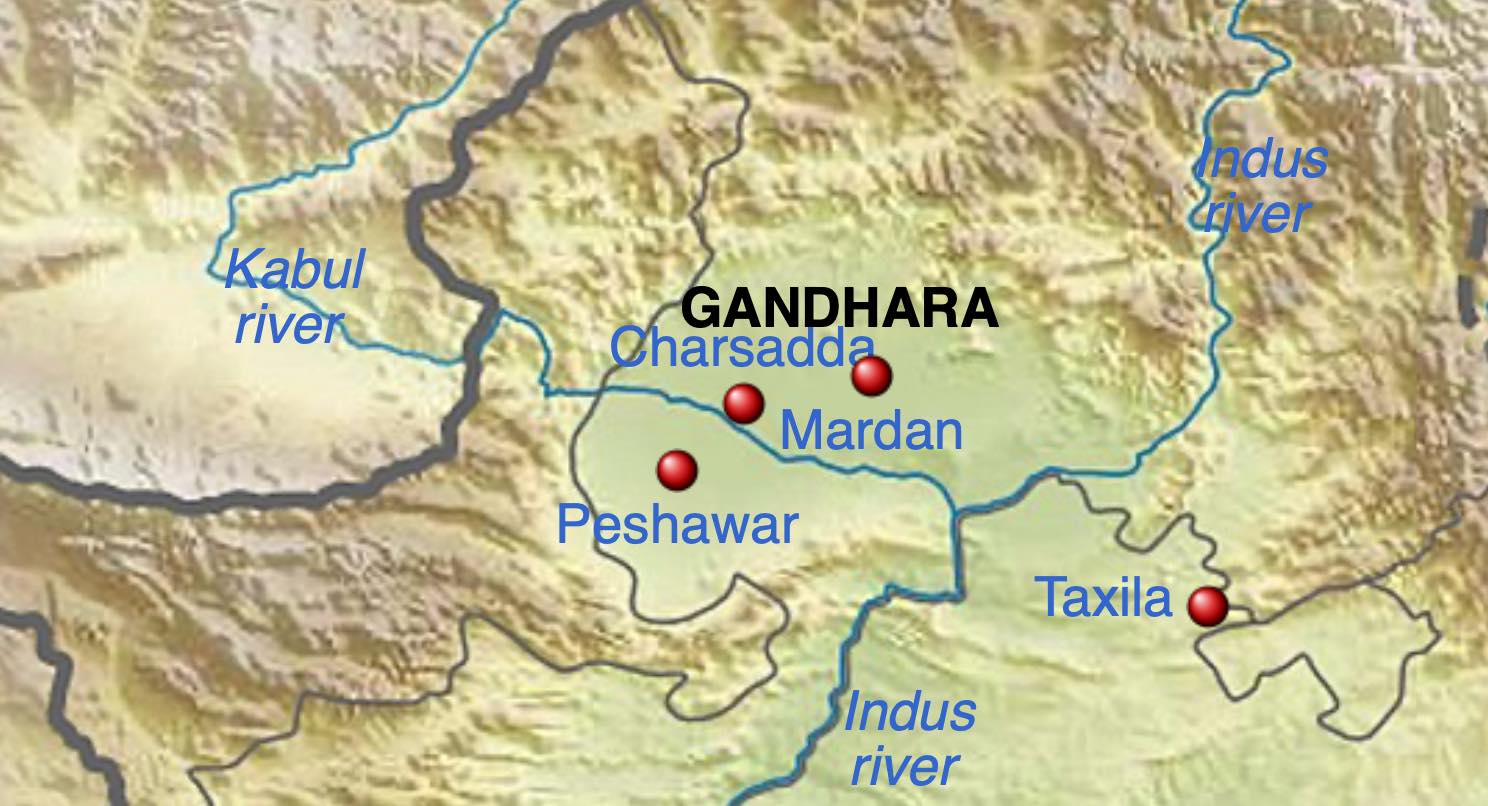

Historical Gandhāra, located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent (modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan), has long been recognized as a significant cultural and historical crossroads. Its strategic position along the ancient trade routes connecting Central Asia, Persia, and India facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and religious beliefs. This unique geographical context allowed Gandhāra to become a melting pot of diverse influences, particularly during the periods of Achaemenid, Hellenistic, Mauryan, Indo-Greek, and Kushan rule.

Approximate geographical region of Gandhara in South Asia, covering today’s northern India, eastern Afghanistan, and Pakistan (top). The region is centered on the Peshawar Basin, in present-day northwest Pakistan (bottom). The region’s strategic position along the ancient trade routes connecting Central Asia, Persia, and India facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and religious beliefs. This unique geographical context allowed Gandhāra to become a melting pot of diverse influences, particularly during the periods of Achaemenid, Hellenistic, Mauryan, Indo-Greek, and Kushan rule. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Achaemenid legacy

Gandhāra’s historical importance begins with its integration into the Achaemenid Empire during the reign of Darius I (6th century BCE), when it became one of the easternmost satrapies (provinces) of the vast Persian administrative system. As part of this imperial network, Gandhāra benefitted from sophisticated governance structures, taxation systems, and infrastructure projects such as roads and communication routes that connected it to the imperial capitals in Iran and Mesopotamia.

The Achaemenid Empire at its greatest territorial extent, under the rule of Darius the Great (522–486 BCE). Gandhāra was located in the easternmost part of the empire, which allowed it to serve as a bridge between the Persian heartland and the Indian subcontinent. The Achaemenid influence is evident in the region’s administrative practices, art, and architecture, which would later be adapted and transformed by subsequent cultures. The satrapal system introduced by the Persians created stable political conditions that fostered economic and cultural exchange. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Achaemenid period left a significant cultural and administrative imprint on the region. The satrapal system introduced by the Persians created stable political conditions that fostered economic and cultural exchange. Elements of Iranian art, language, and religious practices were introduced into the region, some of which would persist even after Persian control waned. Notably, the imperial Aramaic script was used for official inscriptions, and Zoroastrian elements may have mingled with local traditions. These early Persian influences set a foundation for Gandhāra’s later role as a crossroads of cultures, long before the arrival of Alexander the Great.

Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic imprint

The arrival of Alexander the Great in 327 BCE marked a decisive turning point in the history of Gandhāra. Following his conquest of the Achaemenid Empire, Alexander advanced into the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent, including Gandhāra. Though his presence was brief, it set into motion profound cultural transformations that would shape the region for centuries.

Alexander’s empire at the time of its maximum expansion. Within a period of a few years, Alexander, later called the Great, had conquered the Persian Empire and reached the borders of India. On his way, he founded many cities, most of them named after him. These colonization efforts and his Greek entourage lay the groundwork for the later Hellenistic influence – and exchange – in the region. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Alexander’s campaign led to the establishment of several Hellenistic settlements and military outposts, some of which evolved into important urban centers such as Alexandria in the Caucasus and possibly other sites that later became part of the Indo-Greek world. These foundations brought with them Greek-style urban planning, coinage, and administrative practices, as well as a significant influx of Greek and Macedonian settlers.

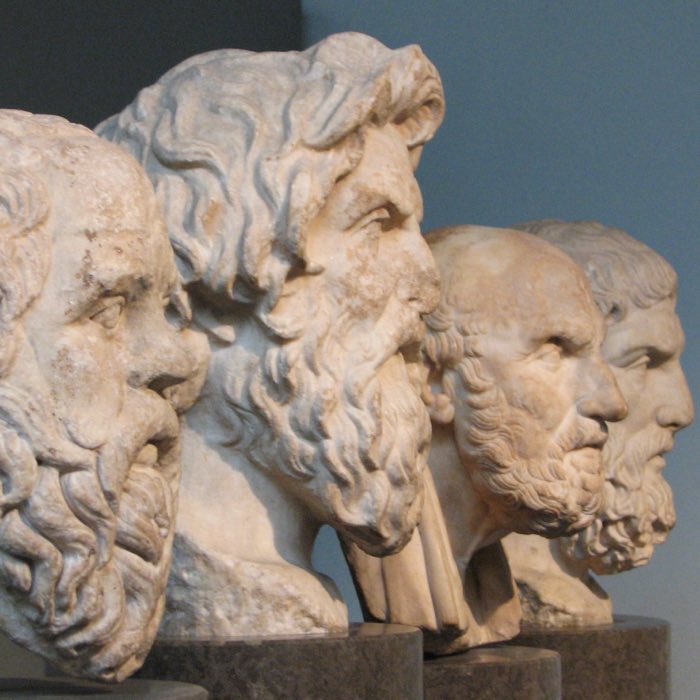

The most enduring legacy of Alexander’s incursion, however, was not political control but cultural. His conquests opened Gandhāra to a sustained Hellenistic influence that permeated its art, architecture, and intellectual life. Greek artistic ideals such as naturalistic human forms, idealized beauty, and detailed anatomical modeling, began to merge with local and Indian motifs. This fusion laid the groundwork for what would become the distinctive Gandhāran artistic style during later periods, especially under the Indo-Greek and Kushan rulers.

Hellenistic kingdoms as they existed in 240 BCE, eight decades after the death of Alexander the Great. Note the Seleucid Empire (green) and the Maurya Empire (brown). The Seleucid Empire was one of the largest empires in history, stretching from the Aegean Sea to the Indus River. It was a melting pot of cultures, languages, and religions, with a diverse population that included Greeks, Persians, and various local peoples. The empire was known for its cosmopolitan cities, such as Antioch and Seleucia, which were centers of trade, culture, and learning. The Maurya Empire, on the other hand, was one of the largest empires in ancient India, known for its political unification and administrative efficiency. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Even after Alexander’s empire fragmented, the Seleucid Empire and later Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms maintained strong cultural ties to the Hellenistic world. Gandhāra thus emerged as a unique cultural crossroads where Greek and Indian traditions were not simply juxtaposed but deeply interwoven.

The Maurya and Āśokan presence

Following the fragmentation of Alexander’s empire, Gandhāra was incorporated into the Mauryan Empire under Chandragupta Maurya around the late 4th century BCE. This marked a significant shift from the Hellenistic to the Indian imperial model. The Mauryan administration extended its centralized bureaucracy and economic systems into the region, creating a new political framework for Gandhāra’s development.

Kingdoms and cities of ancient Buddhism, with Gandhara located in the northwest of this region, during the time of the Buddha (c. 500 BC). The Mahajanapadas were sixteen most powerful and vast kingdoms and republics around the lifetime of Siddhartha Gautama (563–483 BCE), located mainly across the fertile Indo-Gangetic plains, there were also a number of smaller kingdoms stretching the length and breadth of Ancient India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Kingdoms and cities of ancient Buddhism, with Gandhara located in the northwest of this region, during the time of the Buddha (c. 500 BC). The Mahajanapadas were sixteen most powerful and vast kingdoms and republics around the lifetime of Siddhartha Gautama (563–483 BCE), located mainly across the fertile Indo-Gangetic plains, there were also a number of smaller kingdoms stretching the length and breadth of Ancient India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

The most transformative period came during the reign of Emperor Aśoka (c. 268–232 BCE), who embraced Buddhism after the bloody Kalinga War and became one of its most influential patrons. Under Aśoka, Buddhism was actively promoted across the Mauryan territories, including Gandhāra. This had far-reaching effects on the region’s cultural and religious landscape. Monasteries were built, the monastic sangha was supported, and Buddhist missionaries were dispatched both within and beyond the Indian subcontinent.

Traditional depiction of the Maurya Empire under Aśoka as a solid mass of Maurya-controlled territory, c. 250 BCE. The Maurya Empire was one of the largest empires in ancient India, and Aśoka’s reign is often considered a high point in Indian history. His policies of non-violence, religious tolerance, and support for Buddhism had a lasting impact on the region and beyond. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Aśoka’s presence in Gandhāra is attested by the discovery of several of his rock edicts in the region, written in Kharosthi and Aramaic, which indicates the linguistic diversity and cultural hybridity of the area. These edicts emphasize moral conduct (dhamma), compassion, non-violence, and support for the Buddhist order. They also reflect Gandhāra’s importance as a strategic and symbolic location for the spread of Buddhism.

The Mauryan and Āśokan period laid the groundwork for Gandhāra’s emergence as a major center of Buddhist thought and artistic expression. The ideological and institutional foundations established at this time would later be built upon by subsequent dynasties, especially the Kushans.

The Indo-Greek kingdoms

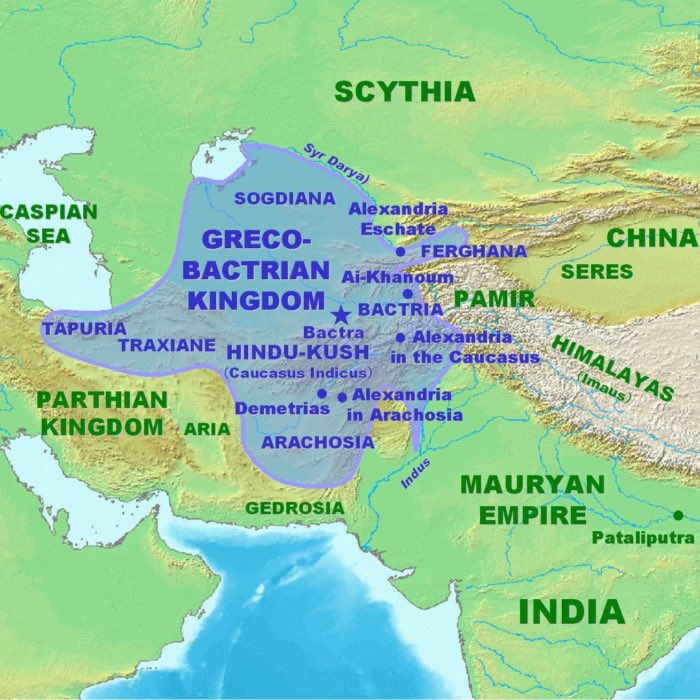

The Indo-Greek kingdoms emerged as a continuation of Greco-Bactrian rule following the collapse of the Mauryan Empire. Around the 2nd century BCE, Greco-Bactrian kings expanded their territory into northwestern India, establishing a series of Indo-Greek polities in Gandhāra and surrounding regions. Among the most notable of these rulers was Menander I (Milinda), whose reign (c. 165–145 BCE) is remembered both for its military success and for his patronage of Buddhism.

Map of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom at its maximum extent, circa 180 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Indo-Greeks governed a multicultural and religiously diverse population, and their rule facilitated a remarkable period of syncretism. Greek political institutions and artistic traditions were fused with local Indian and Iranian customs, giving rise to a hybrid visual and ideological culture. The Indo-Greeks issued bilingual coinage (Greek and Kharosthi), practiced religious tolerance, and maintained strong diplomatic and economic ties along transregional trade routes.

Alexander’s empire at the time of its maximum expansion. Within a period of a few years, Alexander, later called the Great, had conquered the Persian Empire and reached the borders of India. On his way, he founded many cities, most of them named after him. These colonization efforts and his Greek entourage lay the groundwork for the later Hellenistic influence – and exchange – in the region. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The most significant legacy of Indo-Greek rule in Gandhāra lies in the development of a unique artistic tradition that blended Hellenistic realism with Buddhist iconography. It was under their reign that early anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha began to appear, moving beyond the earlier aniconic traditions. These images often portrayed the Buddha in a Greco-Roman style, with wavy hair, finely carved robes, and serene, idealized expressions reminiscent of classical statuary. Relief panels from this period began illustrating scenes from the Buddha’s life with a narrative depth and sculptural sophistication that would define Gandhāran art in the centuries to follow.

Thus, the Indo-Greek period served as both a political and cultural bridge between Hellenistic and South Asian worlds, laying the groundwork for the flourishing of Gandhāran Buddhist art under the Kushans.

The Kushan Empire and its golden age

The Kushan Empire (1st to 3rd century CE) represents the zenith of Gandhāra’s political cohesion and cultural efflorescence. Originating from the Yuezhi nomadic confederation in Central Asia, the Kushans established a powerful and cosmopolitan empire that stretched from Central Asia deep into the Indian subcontinent. Gandhāra, strategically located along major trade routes, emerged as a vital cultural and religious hub during this era.

A map of India in the 2nd century CE showing the extent of the Kushan Empire (in brown) during the reign of Kanishka. Most historians consider the empire to have variously extended as far east as the middle Ganges plain, to Varanasi in the eastern Gangetic plain, or probably even Pataliputra. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Under Kujūla Kadphises, the Kushans consolidated control over the northwest Indian territories, including Gandhāra. This unification laid the groundwork for imperial stability and cross-cultural integration. His successor, Emperor Kaniṣka the Great (r. c. 127–150 CE), is remembered as one of the most influential patrons of Buddhism. Kaniṣka’s reign marked a flourishing of Mahāyāna Buddhism, which received substantial royal support and became a dominant doctrinal current. The famous Kaniṣka reliquary, bearing inscriptions in Kharosthi, attests to his patronage and the rich artistic output of the time.

The Kushan court attracted artists, scholars, and monks from across the empire and beyond. This cosmopolitan atmosphere fueled the development of the distinctive Gandhāran art style, characterized by a synthesis of Greco-Roman naturalism and Indian religious themes. Sculptors created detailed and expressive images of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas, along with narrative panels depicting scenes from Buddhist lore. The use of schist stone, elegant drapery, and realistic anatomy reflect the technical excellence achieved during this period.

The Kushan golden age established Gandhāra as one of the foremost centers of Buddhist art, thought, and transmission. Its influence radiated along the Silk Road, shaping Buddhist cultures in Central Asia and East Asia for centuries to come.

The Gandhāran art style

As a unique artistic tradition that emerged in the context of Gandhāra’s rich cultural and historical milieu, Gandhāran art is characterized by its distinctive style, iconography, and themes. This art form flourished primarily between the 1st and 5th centuries CE, during the height of the Kushan Empire, and is best known for its sculpture, reliefs, and architectural elements associated with Buddhist sites.

General characteristics

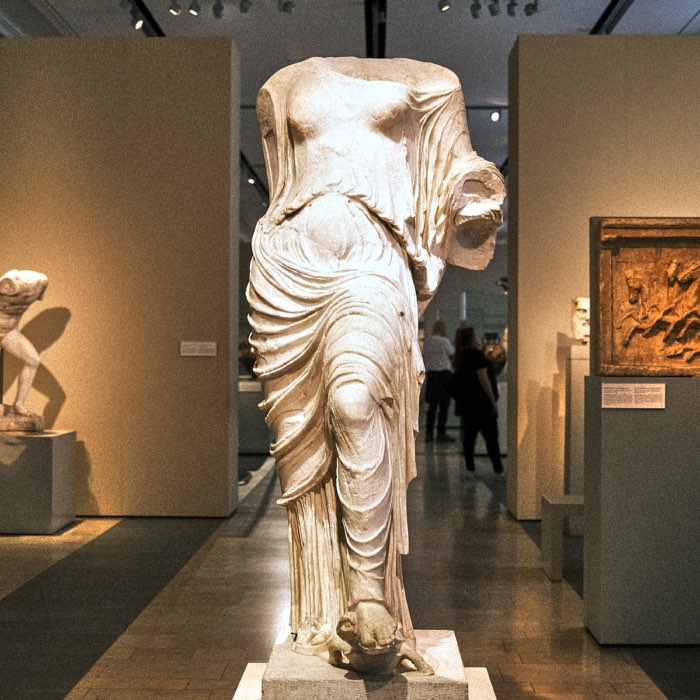

Gandhāran art is most immediately recognizable by its naturalistic human figures, a trait inherited from Greco-Roman sculptural traditions but reinterpreted in a distinctly South Asian religious context. The figures are portrayed with lifelike proportions, expressive gestures, and finely modeled anatomical detail, marking a departure from the more stylized or symbolic depictions in earlier Indian art traditions.

The Buddha on lion throne, Takht-i-Bahi, schist. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC 1.0)

One of the most striking material features of Gandhāran sculpture is the use of gray-blue schist stone, which enabled artists to achieve a high degree of precision and intricate detailing, particularly in the rendering of facial features, hair, and clothing. The hardness of the stone facilitated deep relief carving, which was especially well-suited for the narrative friezes that often adorned stupas, monasteries, and architectural elements.

Couple protectors Pañcika and Hariti, Takht-i-Bahi, schist. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Drapery is another hallmark of the Gandhāran style. Robes are rendered with cascading folds and a tactile sense of weight and flow, clearly influenced by Roman sculptural conventions. These garments often cling to the body, outlining its form while also suggesting movement and grace. This treatment of clothing not only reflects technical virtuosity but also imbues the figures, especially those of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas, with a timeless and idealized presence.

Left: Torso of a Bodhisattva statue, found at Seri_Bahlol, schist, ca. 5th c. CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC 1.0) – Right: Head of a Bodhisattva statue, found at Seri_Bahlol, schist, ca. 100 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC 1.0)

Overall, the general characteristics of Gandhāran art reveal a sophisticated integration of foreign artistic techniques with indigenous religious narratives, resulting in an aesthetic that is both cosmopolitan and deeply rooted in the spiritual aims of Buddhist expression.

Greco-Roman influence

The Greco-Roman influence on Gandhāran art is unmistakable and serves as one of its defining features. This influence was not merely superficial but deeply structural, shaping the formal vocabulary and visual syntax of Buddhist artistic expression in the region.

Seated Buddha, dating from 300 to 500 CE, found near Jamal Garhi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

One of the most visible borrowings is the use of the contrapposto stance — a posture where the figure’s weight rests on one leg, creating a naturalistic S-curve in the body. This technique, rooted in classical Greek statuary, imbues the figure with a sense of dynamic equilibrium and lifelikeness. In Gandhāran art, Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and divine attendants are often portrayed in such poses, lending them a distinctly human presence while maintaining an aura of spiritual serenity.

Stupa drum panel showing the conception of the Buddha: Queen Maya dreams of a white elephant entering her right side, 100–300 CE, carved schist, Jamal Garhi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The facial features of many Gandhāran sculptures likewise reflect Greco-Roman ideals of beauty. Figures are rendered with oval faces, straight noses, almond-shaped eyes, and wavy hair meticulously carved in overlapping curls — reminiscent of Apollo or other classical deities. These physiognomic traits, while adopted from Western art, were recontextualized to portray Eastern religious figures, most notably the Buddha.

Architectural motifs such as Corinthian columns, fluted shafts, and acanthus leaf decorations adorn many Gandhāran stupas, gateways, and niches. These elements, derived from classical temple architecture, were adapted into Buddhist contexts, reinforcing the cosmopolitan nature of Gandhāran sacred spaces.

Indo-Corinthian capitals from Jamal-Garhi. Capitals like these are characterized by their intricate floral and acanthus leaf motifs, which were adapted from classical Greek architecture. The Indo-Corinthian style represents a unique fusion of Hellenistic and local artistic traditions, showcasing the cultural syncretism that defined Gandhāran art. These capitals were often used to adorn columns and architectural elements in Buddhist stupas and monasteries, reflecting the region’s rich artistic heritage.Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Intriguingly, Gandhāran reliefs also incorporate depictions of hybrid mythological beings and foreign iconography. For example, figures resembling centaurs, cherubs, and Atlas-like atlantes can be found in narrative panels and decorative borders. These borrowings were not simply decorative; they reflected a world where artistic motifs traveled alongside merchants, pilgrims, and diplomats across the Silk Road.

The Greek god Atlas, supporting a Buddhist monument, Hadda, Afghanistan, c. 100 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) (modified)

In sum, the Greco-Roman influence in Gandhāran art was transformative. It did not displace local traditions but rather enriched them, giving rise to a hybrid aesthetic that would profoundly shape the visual language of Buddhism across Asia.

Buddhist themes in Gandhāran art

Gandhāran art represents a pivotal moment in the history of Buddhist visual culture, particularly through its role in the transition from aniconic to iconic representations of the Buddha. In earlier Indian Buddhist traditions, the Buddha was depicted symbolically — through footprints, the Bodhi tree, the empty throne, or the dharma wheel. These symbols conveyed presence through absence, adhering to doctrinal sensitivities about representing the enlightened one in human form.

Meditating Bodhisattva. Schist, Sahr-i-Bahlol. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

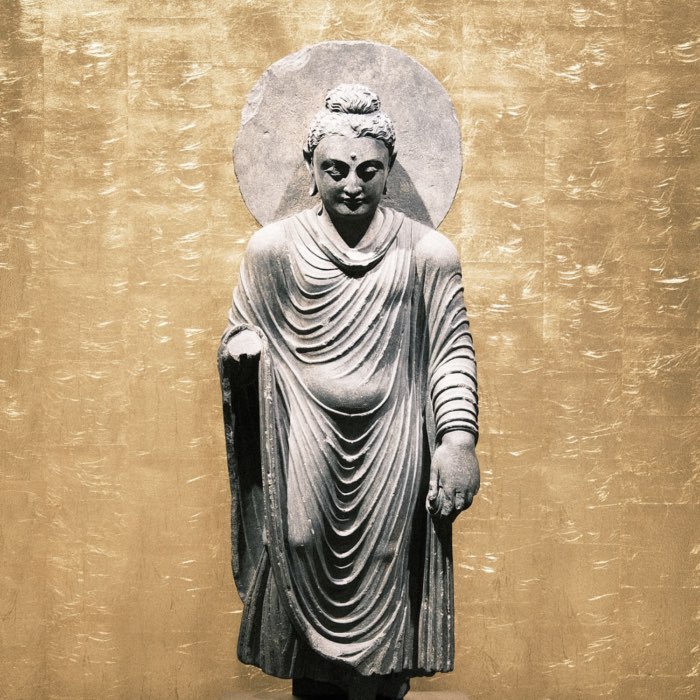

However, in Gandhāra, this reticence gave way to a bold and innovative artistic transformation. The Buddha was now shown as a fully anthropomorphic figure — calm, serene, clothed in monastic robes, and endowed with canonical features such as the ushnisha (cranial protuberance), urna (forehead mark), and elongated earlobes. These early iconic images emerged not only from doctrinal evolution but also from the influence of Hellenistic sculptural techniques, which provided a formal language to render the Buddha with dignity and grace.

Narrative reliefs also became a hallmark of Gandhāran Buddhist art. Carved panels illustrated key events from the Buddha’s life: his birth at Lumbinī, the Great Departure, Enlightenment under the Bodhi tree, the first sermon at Sarnath, and the Parinirvana. These episodes were often framed within elaborate architectural motifs and populated with attendants, celestial beings, and symbolic elements, enhancing their pedagogical and devotional appeal.

In addition to the historical Buddha’s biography, Gandhāran art incorporated Jātaka tales — accounts of the Buddha’s previous lives — which offered moral instruction and emphasized the continuity of karmic merit. With the rise of Mahāyāna Buddhism, Gandhāran sculptors began including Bodhisattvas such as Avalokiteśvāra and Maitreya, whose depictions merged spiritual aspiration with princely iconography. These figures reflect a cosmological expansion and devotional pluralism that resonated with emerging Mahāyāna ideals.

Bronze statue of Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva, with fearlessness mudrā, 3rd century CE, Gandhāra. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Thus, Buddhist themes in Gandhāran art not only narrate the life of Siddhartha Gautama but also encode doctrinal shifts, devotional practices, and the evolving vision of the Buddhist cosmos. The result is a richly textured artistic tradition that bridges the historical and the sacred, the narrative and the transcendental.

Key iconographic innovations

Gandhāran art introduced and standardized several iconographic features that became enduring symbols of Buddhist visual culture across Asia. Chief among them is the fully anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha, who is consistently portrayed with three key identifiers: the halo (prabhāmaṣala), the urna (a dot or spiral on the forehead), and the ushnisha (a cranial bump symbolizing wisdom). These elements, while present in earlier traditions in symbolic or textual form, found their first widespread sculptural representation in Gandhāra. The halo underscores the Buddha’s divine radiance; the urna, his spiritual insight; and the ushnisha, his transcendent knowledge.

The Buddha’s attire in Gandhāran sculptures reflects another important innovation: the rendering of monastic robes with deep, rhythmic folds reminiscent of Greco-Roman togas. These robes, often clinging to the body, are depicted with such anatomical precision and dynamic movement that they elevate the figure’s presence, conveying both ascetic simplicity and majestic serenity. This treatment set a visual standard for Buddhist monastic iconography in many later traditions.

Equally innovative is the depiction of Bodhisattvas in Gandhāran art. Unlike the Buddha, these figures are often shown adorned with elaborate jewelry, coiffed hair, crowns, and princely garments, symbolizing their active compassion and ongoing presence in the worldly realm. Their physical posture frequently mirrors Hellenistic models: relaxed contrapposto stances, expressive hand gestures (mudrās), and a confident yet serene bearing. These attributes communicate both accessibility and sublimity, helping to define the Bodhisattva ideal for future generations.

Together, these iconographic conventions forged in Gandhāra shaped the visual language of Mahāyāna Buddhism and laid the groundwork for Buddhist art in Central Asia, China, Korea, and Japan. Their enduring influence underscores Gandhāra’s pivotal role in the global history of religious art.

Major archaeological sites

The archaeological sites of Gandhāra are a testament to the region’s rich cultural and religious history. These sites, which include stupas, monasteries, and urban centers, provide invaluable insights into the artistic, architectural, and spiritual dimensions of Gandhāran civilization. Below are some of the most significant sites that exemplify the region’s historical and artistic legacy.

Many stupas, such as the Shingerdar stupa in Ghalegay, are scattered throughout the region near Peshawar. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Takht-i-Bahi

Takht-i-Bahi is one of the most prominent and well-preserved monastic complexes of ancient Gandhāra, located near present-day Mardan in northwestern Pakistan. Established in the early 1st century CE and continuously occupied until the 7th century, the site exemplifies the architectural and spiritual aspirations of the region’s Buddhist communities. It comprises a main stupa court, votive stupas, assembly halls, meditation cells, and residential quarters, arranged in a terraced layout on a hilltop that offers both seclusion and panoramic views. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1980, Takht-i-Bahi provides invaluable insights into the monastic life, architectural ingenuity, and ritual practices of Gandhāran Buddhism.

Conjectural restoration of Takht-i-Bahi, a major Buddhist monastery in Mardan, Pakistan, 1946. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Takht-i-Bahi, a view of the site’s main cluster of ruins. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Takht-i-Bahi, aerial view of the ruins of the monastery. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Jamal Garhi and Sahri Bahlol

Jamal Garhi and Sahri Bahlol are two additional key monastic sites that attest to the breadth and diversity of Buddhist architectural activity in the Gandhāra region. Jamal Garhi, situated in the Malakand District, flourished from the 1st to the 5th century CE and is notable for its intricately carved schist panels depicting scenes from the Buddha’s life and Jātaka tales. The site offers evidence of an extensive monastic complex that likely functioned as a major educational and devotional center. Sahri Bahlol, located near Takht-i-Bahi, is an associated hilltop complex that further supports the notion of clustered monastic settlements interconnected by geography and pilgrimage routes. Together, these sites illustrate the scale and sophistication of Buddhist institutions in ancient Gandhāra.

Ruins of Jamal Garhi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Excavations at Sahri Bahlol in 1911-1912. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Taxila

Taxila, perhaps the most archaeologically complex city of ancient Gandhāra, was a cosmopolitan urban center that saw successive waves of Achaemenid, Greek, Mauryan, Indo-Greek, Scythian, Parthian, and Kushan influence. Located at the junction of Central and South Asia, Taxila was a vital hub of commerce, religion, and education. The city comprises multiple excavated sites, including Bhir Mound (the earliest settlement with Achaemenid and early Mauryan layers), Sirkap (a Hellenistic city built on a grid pattern), and Dharmarajika (a major stupa and monastic complex attributed to the Mauryan period). These layers reflect the city’s long and syncretic history, where Buddhist, Hellenistic, and indigenous traditions coexisted and coalesced. Taxila’s material remains — from coins and inscriptions to sculpture and architecture — make it a key site for understanding the evolution of Gandhāran civilization.

Taxila’s ruins, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, date from as early as 1000 BCE. Here: The Double-Headed-Eagle Stupa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Dharmarajika Stupa, a Mauryan-era Buddhist stupa near the city of Taxila. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

View over the ruins, including streets, of Sirkap, Taxila. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

A stupa from the 1st century BCE, Sirkap, Taxila. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

A votive stupa/tomb at the Jaulian monastery, Taxila. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Ruins of the Buddhist Jaulian monastery showing living quarters and stupa remains (at the right corner), dating from the 2nd century CE, located in Taxila. Jaulian, along with the nearby monastery at Mohra Muradu, form part of the Ruins of Taxila – a collection of excavations that were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Map of the Jaulian monastery and stupa area. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Cultural and philosophical exchanges

The cultural and philosophical exchanges that took place in Gandhāra were instrumental in shaping the region’s unique identity as a crossroads of civilizations. The interactions between Hellenistic, Persian, Indian, and Central Asian cultures fostered a dynamic environment where ideas, beliefs, and artistic practices converged and transformed.

Transmission of Buddhist ideas along trade routes

Gandhāra’s geographic location at the crossroads of Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent positioned it as a critical node along the Silk Road, facilitating the transmission of religious, artistic, and philosophical ideas between East and West. As a vibrant center of Buddhist learning and visual culture during the Kushan period, Gandhāra became a launching point for the dissemination of Mahāyāna Buddhism and its associated iconography to regions far beyond its borders.

Monks, merchants, and pilgrims traveling along trade routes carried not only material goods but also sacred texts, relics, and artistic motifs. Gandhāran stupas and monasteries served as both religious sanctuaries and intellectual hubs where teachings were preserved, elaborated, and shared. The visual conventions developed in Gandhāra such as the anthropomorphic Buddha image with Hellenistic features, spread rapidly through Central Asia, influencing the development of Buddhist art in regions such as Bactria, the Tarim Basin, and eventually China.

This transmission is visible in early Central Asian Buddhist sites such as Miran and Khotan, where murals and sculptures echo Gandhāran stylistic elements. As the tradition moved eastward, these forms were further adapted to local tastes and materials, eventually shaping the monumental cave complexes of Yungang and Longmen in northern China. Gandhāra thus played a foundational role in the cross-cultural fertilization that defined Buddhist art along the Silk Road, embedding its aesthetic and doctrinal innovations into the religious fabric of the greater Eurasian world.

Multilingualism and inscriptions

The cultural and linguistic landscape of Gandhāra was notably diverse, reflecting its role as a confluence of civilizations. This multilingualism is most vividly evidenced in the region’s inscriptions, manuscripts, and coinage, which display a rich interplay of scripts and languages, including Greek, Kharosthi, Aramaic, and Gāndhārī Prakrit.

One of the most remarkable features of Gandhāran epigraphy is the presence of bilingual Greek-Kharosthi inscriptions. These inscriptions, found on stone slabs, reliquaries, and coins, were often issued by Indo-Greek and Kushan rulers and served both administrative and religious functions. They reflect the coexistence and mutual intelligibility of Hellenistic and South Asian cultures. The use of Greek, a language of high culture and governance, alongside Kharosthi, a script derived from Aramaic and adapted for Prakrit languages, underscores the region’s polyglot character and its pragmatic approach to governance and communication.

Gāndhārī, a Middle Indo-Aryan language closely related to Sanskrit, was the principal medium for early Buddhist literature in the region. Written in the Kharosthi script, Gāndhārī texts constitute some of the oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts in the world. These fragile birch bark scrolls, discovered in sites such as Hadda and Bamiyan and now housed in collections like the British Library, contain early versions of sutras, vinaya texts, and commentaries that shed light on the transmission and regional adaptations of Buddhist doctrine.

Together, these inscriptions and manuscripts reveal a culture of intellectual openness and administrative flexibility. They also provide critical evidence for the early development of Mahāyāna Buddhism and the ways in which Gandhāra served as both a transmitter and a translator, linguistically and culturally, of Buddhist teachings across Asia.

Legacy and influence

The legacy of Gandhāra extends far beyond its geographical boundaries, leaving an indelible mark on the history of Buddhism and the development of artistic traditions across Asia. The region’s unique synthesis of Hellenistic, Persian, and Indian influences not only shaped its own cultural identity but also facilitated the transmission of Buddhist thought and art to distant lands.

Influence on Central and East Asian Buddhist art

The visual and doctrinal innovations of Gandhāran Buddhism reverberated far beyond the region, profoundly shaping the trajectory of Buddhist art in Central and East Asia. As Gandhāran monks, traders, and pilgrims carried Mahāyāna teachings and iconography along the Silk Road, they laid the foundations for new artistic traditions that adapted and localized the Gandhāran style.

Buddhist expansion in Asia. This map shows the spread of Buddhism from its origins in India to various regions across Asia, including Central Asia, China, Korea, and Japan. Mahayana Buddhism first entered the Chinese Empire (Han dynasty) through the Silk Road during the Kushan Era. The overland and maritime “Silk Roads” were interlinked and complementary, with trade routes facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural practices. This interconnectedness allowed for the dissemination of Buddhist teachings and art across vast distances, ultimately leading to the establishment of Buddhism as a major religious and cultural force in Asia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

One of the clearest instances of this transmission is found in the Yungang and Longmen cave complexes in northern China, which were begun in the 5th and 6th centuries CE under the Northern Wei and later dynasties. The early Buddha images in these caves bear striking stylistic similarities to their Gandhāran predecessors: elongated ears, draped robes with rhythmic folds, and facial features that reflect the Greco-Buddhist aesthetic. Over time, these elements were gradually transformed to conform to Chinese artistic norms, but the foundational influence remained visible for centuries.

Buddha Daibutsu statue, Kamakura, Japan, cast in bronze in the year 1252 CE (Kenchō 4), during the Kamakura period. The deep and lasting impact of Hellenistic influences on Buddhist art is evident in the artistic traditions that emerged in Gandhāra and later spread throughout Asia. The blending of Greek and Indian aesthetics in the representation of the Buddha and other figures laid the groundwork for a rich visual language that would resonate across cultures, influencing Buddhist art in regions as far away as Japan, China, and Southeast Asia. For instance, the Buddha is commonly depicted wearing a robe similar to that of Hellenistic deities, with a serene expression and (often) a halo, as seen in the Kamakura Daibutsu. This fusion of styles reflects the enduring legacy of Greco-Buddhist art and its profound impact on the development of Buddhist iconography across Asia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

In Central Asia, particularly in the regions of modern-day Xinjiang and eastern Iran, Serindian art emerged as a synthesis of Gandhāran, Iranian, and local visual cultures. Bodhisattvas adorned with crowns and jewelry, delicate narrative reliefs, and richly painted murals from sites such as Kucha, Miran, and Bezeklik demonstrate the persistence and adaptation of Gandhāran iconographic and stylistic conventions. These artworks reveal the far-reaching cultural impact of Gandhāra in the shaping of the Silk Road Buddhist visual sphere.

Rediscovery and modern scholarship

Interest in Gandhāra was reignited in the 19th century during the era of British colonial exploration in South Asia. Archaeologists such as Alexander Cunningham, John Marshall, and Alfred Foucher conducted extensive excavations in the region, unearthing stupas, sculptures, coins, and inscriptions that brought the long-forgotten legacy of Gandhāra back into scholarly view. Foucher, in particular, was instrumental in recognizing the Greco-Roman influence in Gandhāran Buddhist art and framing it as a cultural synthesis.

While early scholarship was often shaped by colonial perspectives and aesthetic biases, more recent academic efforts have sought to contextualize Gandhāra within its indigenous and transregional dynamics. Contemporary research integrates archaeological, textual, linguistic, and art historical evidence to reconstruct Gandhāra’s role as a dynamic center of Buddhist innovation and intercultural exchange.

Preservation efforts have also gained traction, especially in light of threats from environmental degradation, looting, and conflict. Organizations such as UNESCO and the Department of Archaeology in Pakistan have worked to conserve key sites like Takht-i-Bahi and Taxila, while digital documentation initiatives aim to make Gandhāran heritage accessible to a global audience. As interest in global Buddhism continues to grow, Gandhāra’s importance as a formative crucible of Buddhist thought and art becomes ever more relevant.

References and further reading

- Behrendt, Kurt A., The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN: 978-0300120271 (read onlineꜛ)

- Kurt A. Behrendt, How To Read Buddhist Art, 2019, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN: 978-1588396730

- Boardman, J., The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity, 2023, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691252834

- Foucher, Alfred, The Beginnings of Buddhist Art and Other Essays in Indian and Central-Asian Archaeology, 1917/1996, Asian Educational Services, ISBN: 978-8120609020

- Marshall, John, Taxila: An Illustrated Account of Archaeological Excavations, 1997, Cambridge University Press (3 Volumes); read it online at archive.orgꜛ

- Richard Salomon, The Buddhist Literature of Ancient Gandhara: An Introduction with Selected Translations, 2018, Wisdom Publications, ISBN: 978-1614291688

- Errington, Elizabeth & Cribb, Joe (eds.), The Crossroads of Asia: Transformation in Image and Symbol in the Art of Ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan, 1992, Ancient India and Iran Trust, ISBN: 978-0951839911

- Nehru, Lolita, Origins of the Gandhāran Style: A Study of Contributory Influences, 1989, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195624724

- Rosenfield, John M., The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans, 1967, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520010918

- David Jongeward, Buddhist Art of Gandhara: In the Ashmolean Museum, 2019, Ashmolean Museum, ISBN-13: 978-1910807224

- John Guy & Vincent Tournier, Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 2023, Book, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN: 9781588396938

- Heather Elgood, Hinduism and the Religious Arts, 2000, A&C Black, ISBN: 9780304707393

- Denise Patry, Donna K. Strahan, & Lawrence Becker, Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, ISBN: 9780300155211

- John Boardman, The Greeks in Asia, 2015, National Geographic Books, ISBN: 9780500252130

- Richard Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization, 2010, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN: 978023062125

- Christopher I. Beckwith, Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia, 2015, Princeton University Press, ISBN 10: 0691166447

- Thomas C. McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, 2001, Allworth, ISBN: 978-1581152036

comments