The Three Marks of Existence: Understanding the core of Buddhist reality

Buddhism presents a radical and insightful perspective on reality, one that diverges sharply from many philosophical and religious traditions. At the heart of this perspective are the Three Marks of Existence (tilakkhaṇa in Pāli, trilakṣaṇa in Sanskrit) — three fundamental characteristics that define all conditioned phenomena. These marks — non-self (anatta), impermanence (anicca), and suffering (dukkha) — offer a profound analysis of existence, revealing why suffering arises and how it can be transcended. By deeply understanding these principles, it is thought, that Buddhist practitioners can cultivate wisdom (paññā), compassion (karuṇā), and ethical conduct (sīla), which detaches from illusions to progress toward liberation (nirvāṇa).

The gankyil (Tibetan) or “wheel of joy” (Sanskrit: ānanda-cakra) is a symbol and ritual tool used in Tibetan and East Asian Buddhism. It consists of three whirling and interconnected blades. It often constitutes the wheel hub in the Dharma Wheel (dharmachakra), symbolizing the Three Marks of Existence: impermanence (anicca), suffering (dukkha), and non-self (anatta). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

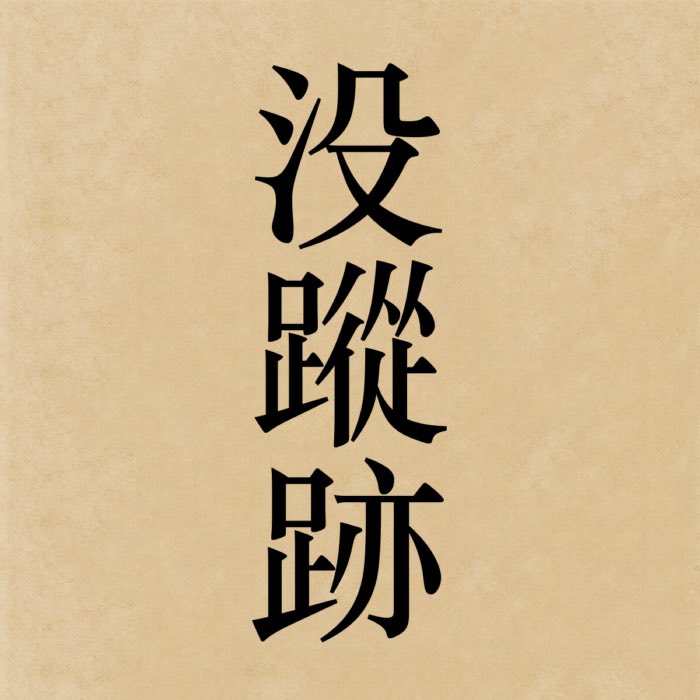

Non-Self (Anatta)

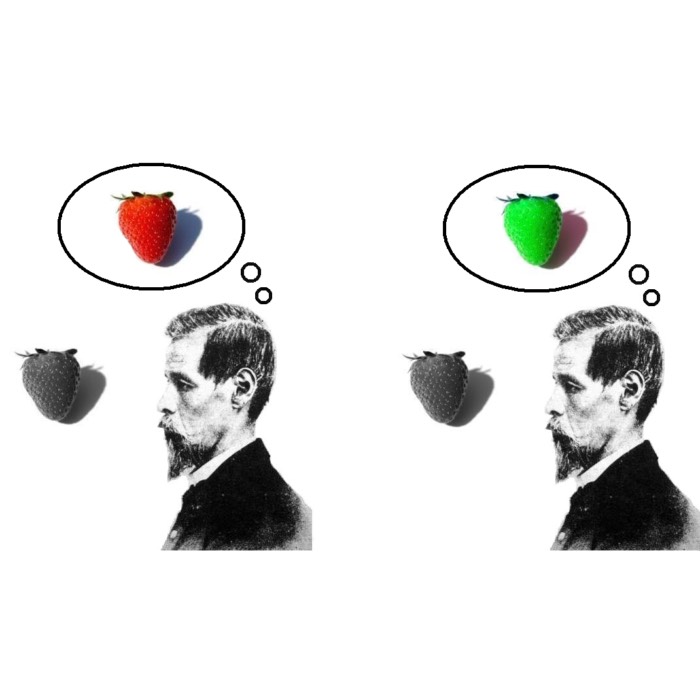

Perhaps the most revolutionary concept in Buddhist thought is anatta (Pāli; Sanskrit: anātman), the doctrine of non-self. Unlike many religious and philosophical traditions that posit a permanent, unchanging soul or essence, Buddhism asserts that no such entity exists. What we call the “self” is merely a collection of ever-changing physical and mental processes known as the Five Aggregates (skandhas): form, sensation, perception, mental formations, and consciousness.

Siddhartha challenged the prevailing ātman (soul) concept found in Brahmanical traditions, arguing that belief in a fixed self leads to attachment, suffering, and rebirth. He taught that clinging to a sense of “I” and “mine” fuels desire and aversion, perpetuating the cycle of suffering.

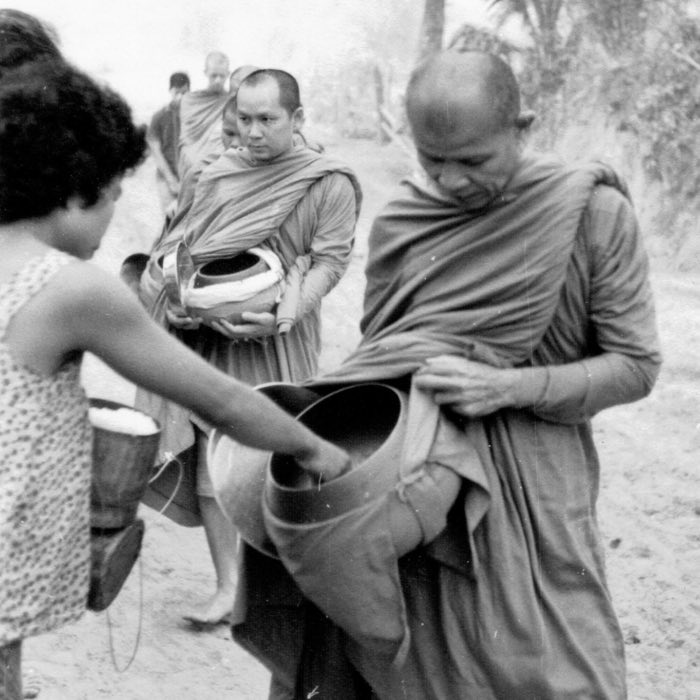

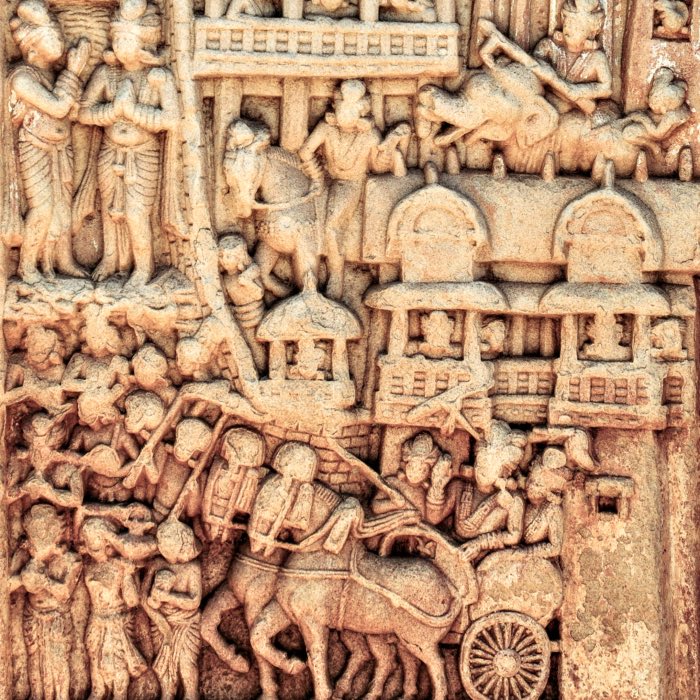

A classic analogy illustrating anatta is found in the Milinda Pañha, where the monk Nāgasena explains to King Milinda that just as a chariot is merely a collection of wheels, axles, and other parts, the self is nothing more than a composition of interdependent aggregates. If these components are examined individually, the entity called “chariot” or “self” disappears — revealing that both are just conceptual designations, not intrinsic realities.

Beyond this, all perceived phenomena are without inherent nature (svabhāva). The deeper one analyzes anything — be it a person, an object, or even a thought — it dissolves into ever-smaller components, none of which possess an independent essence. This insight into emptiness (shunyata) extends the anatta principle beyond the self to all things, reinforcing that everything is dependent on conditions (pratītyasamutpāda) and therefore empty of intrinsic existence.

Within the tradition, understanding anatta is not regarded as an intellectual exercise but as a transformative realization. It reveals that our deeply held notion of a personal identity is merely a fleeting arrangement of conditions, continuously shifting like a river. When one fully grasps this, attachment diminishes, leading to profound freedom. Meditation is regarded within Buddhist practice as a method to directly experience this insight, enabling the dissolution of the illusion of self and the cultivation of detachment, compassion, and wisdom.

We will explore the doctrine of non-self — including its narrative analogies, philosophical implications, and connection to emptiness (shunyata) — in more detail in an upcoming post.

Impermanence (Anicca)

The second of the Three Marks of Existence, anicca (Pāli; Sanskrit: anitya), describes the transient nature of all things. Everything in existence — whether physical objects, mental states, relationships, or even our own bodies — is in constant flux. Nothing remains the same from one moment to the next, and all conditioned phenomena are subject to change. This insight is not merely theoretical but observable in everyday life: seasons shift, emotions fluctuate, buildings decay, and even the cells in our bodies continuously regenerate and die.

However, anicca is not simply an observable trait of particular things — it is the fundamental principle governing the entire universe and time itself. Everything, from the grand scale of galaxies to the smallest subatomic particles, is in perpetual motion and transformation. The very fabric of existence is transient, and no phenomenon — whether material, conceptual, or experiential — remains fixed. This insight is a cornerstone of Buddhist thought, aligning impermanence with Dharma, the universal law that governs reality. Even time itself is not a constant but part of this ever-changing flux.

In early Buddhist texts, Siddhartha Gautama illustrates anicca through various analogies. One common metaphor compares existence to a flowing river: although it appears continuous, the water that composes it is never the same. Similarly, our sense of stability in life is an illusion; what we perceive as solid and enduring is actually a process of constant arising and passing away.

Understanding anicca is fundamental to Buddhist practice because attachment (upādāna) to permanence is a source of suffering. People cling to material possessions, relationships, and identities, hoping to find security in them. However, when these inevitably change or dissolve, suffering arises. By embracing impermanence, one can develop a healthier relationship with change, reducing attachment and fostering equanimity.

Suffering (Dukkha)

The third mark of existence, dukkha (Pāli; Sanskrit duḥkha), is the result of the first two marks. It refers to the inherent unsatisfactoriness and suffering that pervades all conditioned existence. The term dukkha is often translated as suffering, dissatisfaction, or unsatisfactoriness. It encapsulates the existential unease that permeates all conditioned experiences. While some suffering is obvious — such as physical pain, illness, and emotional distress — Buddhism identifies subtler forms as well.

According to Buddhist teachings, dukkha manifests in three primary ways:

- Ordinary suffering (dukkha-dukkha): This includes physical pain, emotional distress, and common hardships of life such as aging, sickness, and death.

- Suffering due to change (vipariṇāma-dukkha): Even pleasurable experiences are ultimately unsatisfactory because they are impermanent. Joyful moments fade, loved ones pass away, and situations fluctuate, causing distress.

- Suffering due to conditioned existence (saṅkhāra-dukkha): This is the most profound level, referring to the fundamental dissatisfaction inherent in being caught in the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsara). It stems from clinging to an illusory sense of self and failing to recognize the nature of reality.

Understanding dukkha is the first step toward overcoming it. Siddhartha’s teachings do not advocate pessimism but rather a realistic acknowledgment of suffering as the basis for liberation. By recognizing suffering, its causes, and the possibility of cessation, practitioners can work toward a state of lasting peace and freedom.

Since dukkha extends far beyond its role as one of the Three Marks of Existence and serves as the foundation of the Four Noble Truths, we will examine its nuances, causes, and the various methods Buddhism offers to transcend it in a separate post.

The interconnection of the Three Marks

The Three Marks of Existence are deeply interwoven, each building upon the other to explain the nature of reality and the roots of human suffering. From the ground up, the structure reads: all things fundamentally lack a self or intrinsic nature (anatta). Because of this absence of enduring essence, all phenomena are inherently impermanent (anicca). And because we try to hold on to what is impermanent, all conditioned existence is marked by suffering (dukkha). Even things that are not inherently painful become so through their transience.

Reversing the perspective, we can say: all existence is unsatisfactory because it is impermanent; and all is impermanent because there is no stable essence behind any phenomenon. Siddhartha’s radical insight into the nature of reality thus links suffering not to some external force, divine will, or cosmic punishment, but to a fundamental misunderstanding of existence itself. Unlike many religious traditions that locate the cause of suffering in the hands of gods or fate, Buddhism identifies it as a consequence of delusion — particularly the mistaken belief in a permanent self and in the possibility of securing lasting satisfaction in a world of constant change.

We suffer because we cling to what can never truly be grasped. Neither we ourselves nor the objects of our craving possess stable being; and yet, our desires are shaped as if they did. Our suffering, then, arises from this mismatch between how things are and how we want them to be. In this way, Buddhism offers not merely a diagnosis but a shift in perception: liberation (nirvāṇa) does not come from resisting impermanence or defending the illusion of a fixed self, but from insight into reality as it is.

When one fully internalizes that suffering arises due to craving (tanhā) for what is inherently transient, and that the self is an artificial construct born of conditioned factors, the possibility of true freedom emerges. This insight is at the heart of Buddhist practice, shifting perception from grasping to letting go, from illusion to wisdom (paññā). Through meditation and mindfulness, practitioners cultivate the ability to move beyond suffering by aligning themselves with the natural flow of impermanence rather than struggling against it. This insight is not based on blind faith, but on direct experiential realization—insight into these three marks dismantles illusions and leads to genuine liberation.

Conclusion

The Three Marks of Existence offer a lens through which to view reality as it truly is. Rather than seeing impermanence as a disturbance, suffering as an anomaly, or the self as an unshakable truth, Buddhism presents these as natural and inseparable aspects of existence. Anicca (impermanence) ensures that no phenomenon remains fixed; dukkha (suffering) arises as a consequence of craving stability in an ever-changing world; and anatta (non-self) reveals that no enduring identity can be found within this flux. Together, they illuminate the structure of conditioned reality.

Understanding these principles is not meant to foster detachment in a nihilistic sense but to cultivate freedom from the illusions that cause suffering. By seeing that all things — including the self — are without intrinsic existence, practitioners move beyond attachment and aversion. This insight, rather than being abstract, is deeply practical: it leads to greater equanimity, compassion, and wisdom in everyday life. Meditation, ethical living, and mindful awareness are not separate from this realization but serve as direct means to embody it.

The Buddha’s path does not rely on speculation or dogma but on direct experiential understanding. According to Buddhist thought, by deeply realizing anicca, dukkha, and anatta, individuals are said to dissolve the mistaken perceptions that bind them to suffering. In doing so, they open the possibility of true liberation (nirvāṇa), aligning themselves with the natural unfolding of existence rather than resisting it.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

comments