Bodhidharma’s coming from the West: Reassessing the myth and its historical substance

Bodhidharma occupies a singular position in the history of Zen Buddhism: a semi-legendary figure who, though sparsely attested in early sources, is later credited with founding the Chán (Zen) tradition in China. His image — a fierce, bearded monk arriving from the West, meditating for years in silence, and sparring intellectually with an emperor — has become iconic, yet his historical reality remains elusive. This post does not aim to either venerate Bodhidharma as a saintly founder or debunk him as a fabricated myth. Instead, it seeks to assess what can be understood of Bodhidharma as a symbol of a specific turning point in the development of East Asian Buddhism.

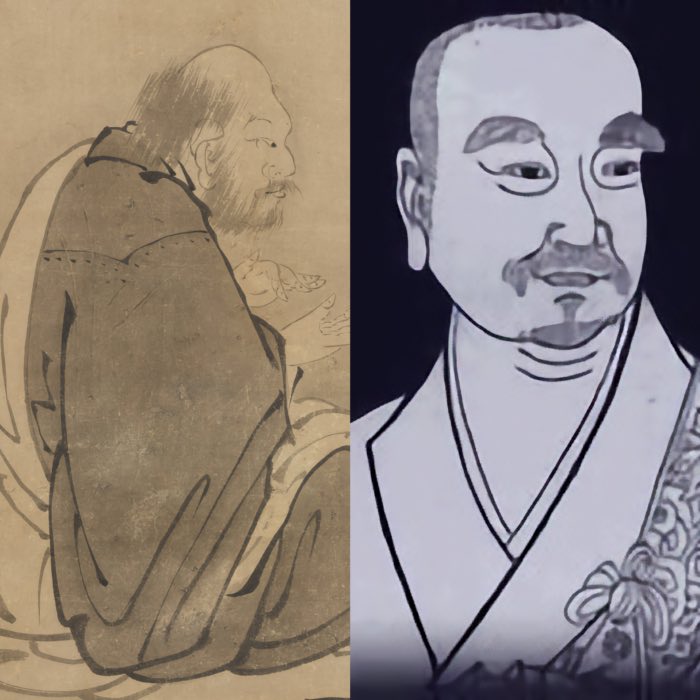

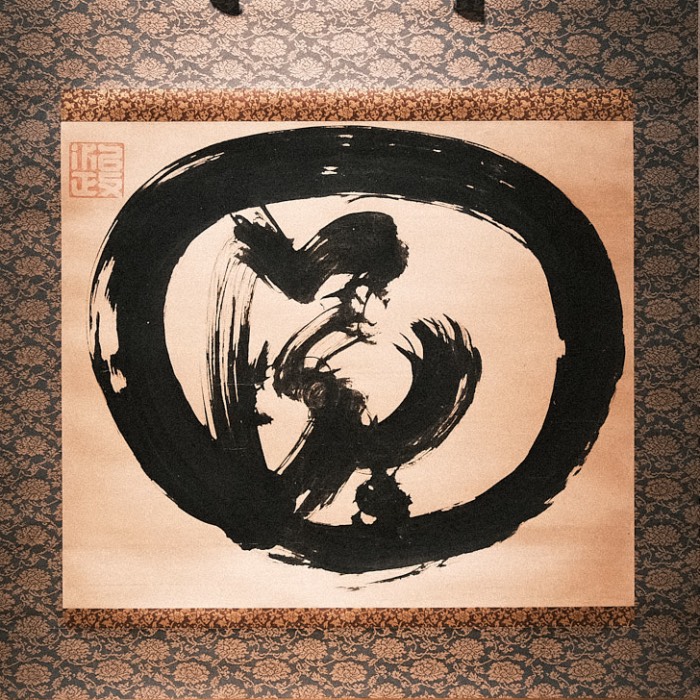

Huike offering his arm to Bodhidharma, ink wash painting by Sesshū Tōyō, 1496, Japan. This dramatic scene illustrates one of the most famous legends in Zen history. According to the story, Huike, a devoted seeker of enlightenment, approached Bodhidharma, who was meditating in silence, and requested to become his student. Bodhidharma, known for his rigorous and uncompromising approach, initially rejected Huike, testing his resolve. Undeterred, Huike stood outside in the snow, demonstrating his sincerity and determination. After hours of waiting, in an extraordinary act of devotion, Huike severed his own arm and presented it to Bodhidharma as a gesture of his unwavering commitment to the path of awakening. Moved by this extreme display of dedication, Bodhidharma finally accepted Huike as his disciple, marking the beginning of a profound teacher-student relationship. This story, though likely apocryphal, symbolizes the intense discipline and perseverance valued in the Chán (Zen) tradition, as well as the transformative power of the master-disciple bond. Stories like this obscure the historical Bodhidharma beneath accumulated layers of myth and symbolism — a process this post aims to critically investigate. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The state of Buddhism in China before Bodhidharma

By the time Bodhidharma is traditionally believed to have arrived in China during the early 6th century, Buddhism had already been present in the region for several centuries. From its initial introduction during the Han dynasty, Buddhism developed through successive waves of translation activity, missionary efforts, and the adaptation of foreign teachings into the Chinese intellectual landscape. Key figures such as An Shigao and Kumarajiva helped lay a doctrinal foundation by translating a vast corpus of Indian texts into Chinese, allowing Buddhist philosophy to take root.

However, by the 5th century, Chinese Buddhism had entered a phase marked by increasing scholasticism and ritual formalism. Doctrinal schools such as the Sanlun and Tiantai began to systematize Buddhist philosophy, often engaging in intricate exegetical debates. These developments were accompanied by an expansion of temple complexes, a rise in monastic hierarchy, and a growing emphasis on ritual observance, merit-making, and scriptural authority. While these structures supported the institutionalization of Buddhism, they also risked turning practice into formality.

Simultaneously, tensions emerged between Buddhist teachings and the indigenous philosophical traditions of Daoism and Confucianism. Buddhist metaphysical concepts and its monastic ethos clashed with Confucian ideals of social order and filial piety, while its soteriological orientation often seemed abstract in comparison to Daoist notions of naturalness and spontaneity. In response, Chinese monks began adapting Buddhist teachings in ways that resonated with local sensibilities, setting the stage for the emergence of more practice-oriented movements.

Furthermore, Buddhism became increasingly entwined with political structures. The ruling elite often patronized Buddhist institutions for purposes of social stability, public morality, and imperial legitimacy. Monasteries were sometimes granted land and tax exemptions, and certain rituals were used to reinforce the authority of emperors. This patronage, while beneficial to Buddhist expansion, also contributed to a growing ossification: Buddhism, once a counter-cultural spiritual movement, risked becoming a tool of statecraft and social control.

By the early 6th century, many within the Buddhist community recognized a disconnect between the original aims of the Dharma and its current institutional expression. There was a growing demand for a return to foundational practices — particularly meditation — as a means of revitalizing the tradition. In this environment, a figure like Bodhidharma, who emphasized direct insight, non-reliance on texts, and rigorous meditative discipline, could serve as both a symbol and a catalyst for reform. Whether historical or not, the conditions into which he was inserted were undeniably fertile for a corrective voice that would recenter Buddhism around experiential realization rather than doctrinal accumulation.

The historical Bodhidharma: Between text and legend

The figure of Bodhidharma occupies a liminal space between history and legend. The earliest known references to him appear in texts such as the Luoyang Jialanji (The Record of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang, c. 547 CE) and the Xu Gaoseng Zhuan (Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks, compiled in 645 CE). These sources present a fragmented and sometimes contradictory portrait. In some accounts, he is portrayed as a South Indian prince turned monk who traveled to China by sea, arriving sometime in the early 6th century. In others, his origins and travels remain vague or symbolic, with more emphasis on his teachings than on verifiable details of his life.

Among the most well-known episodes attributed to Bodhidharma is his encounter with Emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty, a devout Buddhist ruler and major patron of temple-building, sutra copying, and monastic ordination. According to Zen hagiographies such as the Transmission of the Lamp, the emperor proudly recounted his pious deeds and asked Bodhidharma what merit he had earned through them. Bodhidharma’s reply was uncompromising: “No merit whatsoever” (無功德, wú gōngdé). When Emperor Wu pressed further, asking, “What is the highest meaning of the holy truth?”, Bodhidharma answered, “Vast emptiness, nothing sacred” (廓然無聖, kuòrán wú shèng). The final exchange came when the emperor, perplexed, asked, “Who are you standing before me?” to which Bodhidharma replied, “I don’t know” (不識, bù shí).

These terse and enigmatic replies have become iconic within the Chán tradition, offering layered critiques of Buddhist institutionalism, merit-seeking, and conceptual attachment. The dismissal of merit reflects Bodhidharma’s challenge to the transactional understanding of religious practice. Declaring the ultimate truth to be “vast emptiness” aligns him with the Madhyamaka view of śūnyatā (emptiness), yet filtered through Chán’s experiential and immediate lens. Most striking is the final response — “I don’t know” — which expresses the fundamental Chán principle that true insight into one’s nature is not conceptual but direct, beyond language or self-definition. In subverting the categories of identity, piety, and sacred knowledge, Bodhidharma’s words encapsulate a radical non-dualism and rejection of spiritual pretension that would shape the trajectory of Zen thought for centuries to come.

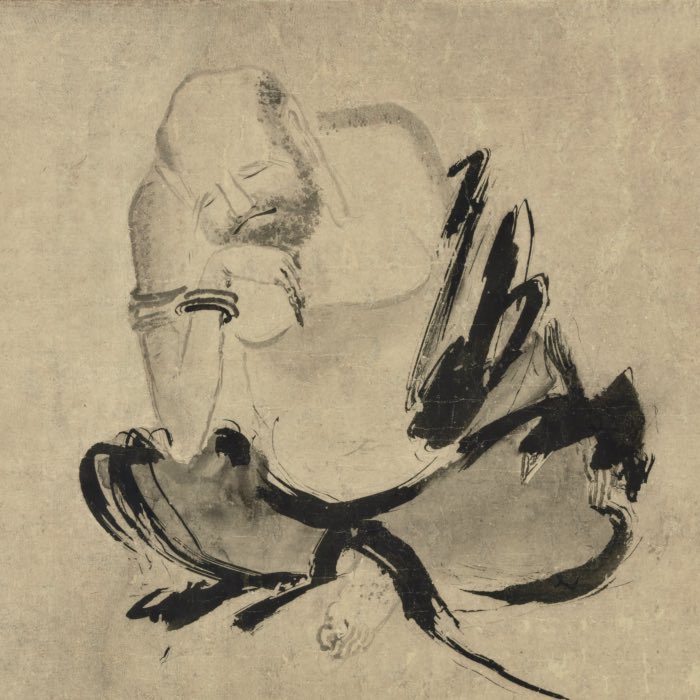

Another legendary element associated with Bodhidharma is his prolonged meditation retreat — reportedly nine years of “wall-gazing” in a cave near the Shaolin Monastery. This austere practice, while historically unverifiable, came to symbolize the extreme commitment to meditative introspection that Chán would later champion. The image of a monk seated in silence, turned inward for nearly a decade, presents an archetype of the uncompromising pursuit of direct experience unmediated by ritual or doctrine. It is this posture — both literal and philosophical — that helped position Bodhidharma as the prototype of the Chán ideal: detached from institutional Buddhism and radically devoted to awakening through direct perception.

Later hagiographies further enriched the legend, crediting Bodhidharma with introducing physical training exercises that evolved into Shaolin martial arts, and establishing him as the first patriarch in a line of Zen transmission. These attributions, while more reflective of later cultural developments than early history, indicate how Bodhidharma’s image was reshaped to serve evolving pedagogical and symbolic needs. The retreat narrative, in particular, reflects the core Zen value that realization is attained not through external acts or scriptural study, but through the inward clarity that comes from unbroken meditative discipline.

To reinforce Bodhidharma’s position in the development of the Chán tradition, later sources constructed a continuous lineage of Dharma transmission stretching back to Śākyamuni himself. According to Zen tradition, Śākyamuni transmitted the Dharma to ten principal disciples:

- Śāriputra

- Maudgalyāyana

- Mahākāśyapa

- Aniruddha

- Subhūti

- Pūrṇa-Maitrayanīputra

- Katyama

- Upāli

- Rāhula (Śākyamuni’s son)

- Ānanda

Zen tradition holds that Mahākāśyapa received the Buddha’s wordless transmission of insight. This foundational moment in Zen lore is encapsulated in the story of the Buddha’s silent teaching by holding up a single udumbara flower during a gathering of disciples. According to the legend, the Buddha offered no verbal teaching, but simply raised the flower before the assembly. All remained silent except Mahākāśyapa, who smiled. In that moment, the Buddha is said to have acknowledged Mahākāśyapa’s direct understanding, stating, “I possess the true Dharma eye, the marvelous mind of nirvāṇa, the true form of the formless, the subtle Dharma gate that does not rest on words or letters, a special transmission outside the scriptures. This I entrust to Mahākāśyapa.”

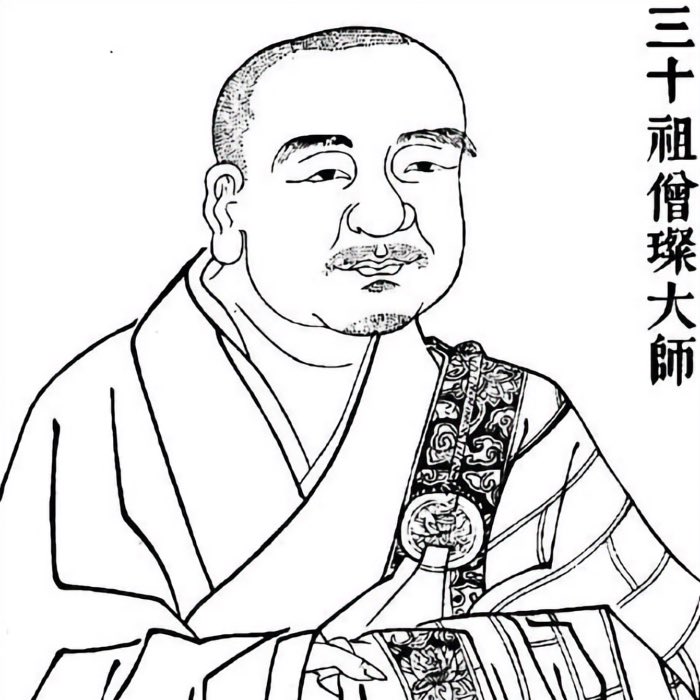

The tale, which appears in later Chán texts rather than early canonical sources, functions as a symbolic origin story for Zen’s emphasis on direct, non-conceptual realization. The udumbara flower — rare and said to bloom only once every several thousand years — serves as a metaphor for the subtle, wordless nature of awakening, accessible only through intimate, experiential insight. Mahākāśyapa’s smile signifies a realization that cannot be taught, only awakened into. This event is thus portrayed as the beginning of an unbroken line of mind-to-mind transmission that eventually leads to Bodhidharma and the founding of Zen in China. The list includes the following figures:

- Mahākāśyapa

- Ānanda

- Śānavāsa

- Upagupta

- Dhrtaka

- Miccaka

- Vasumitra

- Buddhanandi

- Buddhamitra

- Pārśva

- Punyayaśas

- Ānabodhi / Aśvaghoṣa

- Kapimala

- Nāgārjuna

- Kānadeva

- Rāhulata

- Sanghānandi

- Sanghayaśas

- Kumārata

- Śayata

- Vasubandhu

- Manorhita

- Haklenayaśas

- Simhabodhi

- Vasiasita

- Punyamitra

- Prajñātāra

- Bodhidharma

Though historically unverifiable, this transmission scheme was crucial in establishing Zen’s self-understanding as a legitimate heir of the Buddha’s teaching. It provided an institutional and symbolic link between the origins of Buddhism and its meditative revitalization in East Asia, underscoring the continuity between ancient insight and contemporary realization.

Assessing the historical plausibility of Bodhidharma’s life and teachings is challenging, given the scarcity of reliable contemporary sources and the predominance of later hagiographical embellishments. While it is likely that an Indian or Central Asian monk named Bodhidharma did travel to China and became known for a distinctive teaching style, the elaborate biographical and doctrinal attributions were developed and refined by later Chán communities to serve institutional and pedagogical purposes. In this sense, the historical Bodhidharma may be less important than the philosophical function he came to embody: a figurehead for the revival of meditative practice and the rejection of scholastic rigidity. His legend grew in parallel with the evolving identity of Chán Buddhism itself, functioning as a mirror for its core values rather than a factual chronicle.

What “Bodhidharma” represents philosophically

Bodhidharma’s legacy is not merely a matter of historical fact; it is also a philosophical and cultural phenomenon that has shaped the trajectory of East Asian Buddhism. His teachings, whether attributed to him directly or constructed later, reflect a set of values and practices that resonate deeply with the core tenets of Chán. The following themes emerge as central to understanding Bodhidharma’s significance:

Bodhidharma as a symbolic figure

Whether or not Bodhidharma was a historical person, he came to symbolize a decisive turn in the orientation of ]Buddhism](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-05-16-buddhism/) in East Asia. His image, teachings, and associated legends collectively embody a form of Buddhism that emphasizes internal realization over external authority, direct experience over doctrinal elaboration, and meditative discipline over institutional routine. In this way, Bodhidharma functions less as a figure to be historically verified and more as a catalyst in the ongoing project of reforming and revitalizing the Buddhist path.

A special transmission outside the scriptures

One of the most famous slogans attributed to Bodhidharma is: “A special transmission outside the scriptures, not founded on words or letters; pointing directly to the human mind; seeing one’s nature and becoming Buddha.” This phrase captures the essence of Zen’s claim to legitimacy and uniqueness. While not a literal rejection of Buddhist texts, this view prioritizes awakening through direct experience. The phrase reflects a conscious resistance to the scholasticism that had come to dominate Buddhist practice and suggests a return to the immediacy of Siddhartha Gautama’s original insight.

Direct insight and meditation (Dhyāna)

Bodhidharma’s emphasis on dhyāna (meditative absorption) was not novel in the broader context of Indian Buddhism but took on new urgency in the Chinese setting, where ritual and textual study had become dominant. Bodhidharma’s legendary “wall-gazing” practice represented a radical recommitment to seated meditation as the central means of awakening. In Zen, this emphasis evolved into techniques such as zazen (seated meditation) and shikantaza (just sitting), which maintain a direct link to the non-discursive path Bodhidharma is said to have embodied.

Critique of ritual, scholasticism, and institutional Buddhism

Embedded in Bodhidharma’s teachings is a sharp critique of Buddhist practice as it had come to be institutionalized in China. The famous exchange with Emperor Wu illustrates this posture: despite the emperor’s extensive support of Buddhism through temple construction and monastic patronage, Bodhidharma responded that such actions accrued “no merit.” This critique targeted the commodification of Buddhist practice, wherein religious actions were performed as transactions expected to yield karmic rewards. Bodhidharma’s response redirected attention to the inner transformation that cannot be measured or secured through formal acts.

Alignment with Mahāyāna and early Buddhist thought

Though Chán often appears iconoclastic, its foundational teachings align closely with both early Buddhist insights and Mahāyāna developments. The doctrine of śūnyatā (emptiness), central to Madhyamaka philosophy, is echoed in Bodhidharma’s declaration of “vast emptiness.” His insistence on selflessness, impermanence, and liberation through direct realization resonates with the core aims of Siddhartha Gautama’s teaching. Thus, Bodhidharma did not introduce a new religion or philosophical system, but rather served as a renewal of fundamental Buddhist principles, expressed in a stripped-down, practice-oriented form suited to the cultural conditions of medieval China.

Legacy and impact

Bodhidharmā’s legacy is multifaceted, extending beyond the historical figure to encompass a range of symbolic, doctrinal, and cultural dimensions. His influence can be traced through the development of Chán. Buddhism, the construction of a lineage that legitimized its practices, and the broader cultural impact of his image in East Asia.

Influence on early Chán lineages

Bodhidharma’s legacy within Chinese Buddhism rests largely on his symbolic role as the first patriarch of the Chán tradition. Early Chán lineages retrospectively traced their roots to him in order to ground their practices in a lineage that emphasized direct transmission of insight. His reputed emphasis on meditation over scripture resonated deeply with the emerging Chán communities that sought to reorient Buddhism away from scholasticism and institutional excess.

Constructed lineage and institutional identity

The idea of an unbroken lineage from Śākyamuni Buddha to Bodhidharma was constructed and formalized over time by Chán historians and monastic communities. This lineage served both doctrinal and institutional purposes: it legitimized Chán’s distinctive methods, such as kōan practice and silent illumination, and helped establish it as a formally recognized school of Chinese Buddhism. Bodhidharma’s placement as the twenty-eighth patriarch lent weight to the notion of a special transmission outside the scriptures and framed Chán as the guardian of a more authentic Buddhism.

A corrective force in Chinese Buddhism

In the larger context of Chinese religious life, Bodhidharma represented a critique and correction of prevailing Buddhist trends. His austere demeanor, disregard for ritual performance, and emphasis on internal realization offered a counterpoint to the increasingly ritualized and politically co-opted forms of Buddhism endorsed by the elite. Bodhidharma became a symbol of integrity and of returning to the essence of the path — a role that was later expanded and refined by figures like Huineng (638–713), who would go on to articulate the uniquely Chinese features of Chán.

Transregional influence and modern reception

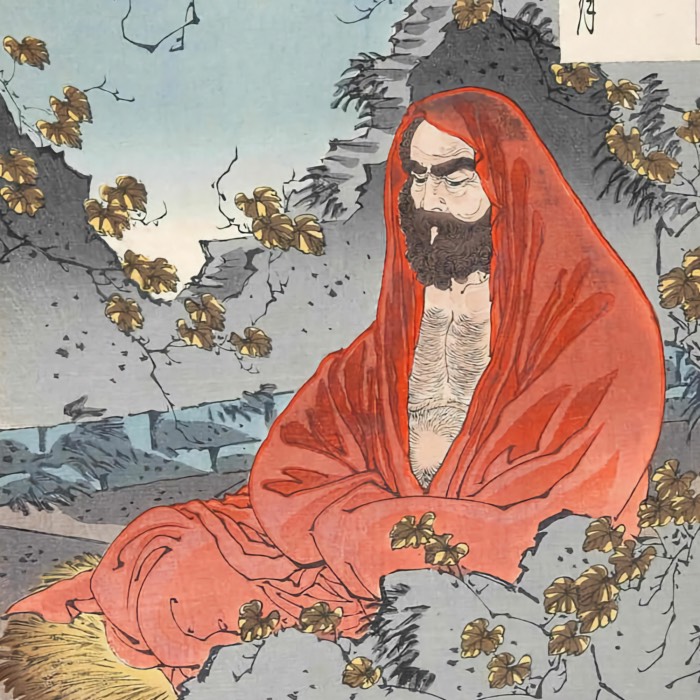

Although Bodhidharma is most closely associated with Chinese Chán, his legend spread widely throughout East Asia. In Korea, he was absorbed into the Seon tradition, where his meditative emphasis was echoed in the practices of later Korean masters. In Japan, he became especially iconic within the Rinzai school of Zen, where he is often depicted in art as a wild-eyed, ascetic figure symbolizing the raw energy of enlightenment. In modern popular culture, Bodhidharma’s story has been mythologized far beyond monastic circles, appearing in martial arts lore, comics, and global representations of Zen. While many of these depictions are historically inaccurate or sensationalized, they testify to the enduring resonance of the figure as a cultural and spiritual archetype.

Taken together, Bodhidharma’s impact is less about his specific biographical details and more about the catalytic role he played in shaping the ethos of Chán: a Buddhism grounded not in texts or temples, but in the lived, moment-to-moment realization of one’s true nature.

Conclusion

Bodhidharma remains a compelling figure not because of historical certainty, but because of the narrative and philosophical role he has come to occupy within the Chán tradition. His symbolic function — as a voice recalling Buddhism to its meditative roots, resisting institutional rigidity, and demanding direct insight into reality — transcends the limits of biographical verification. Whether or not a single historical monk named Bodhidharma accomplished all that later tradition claims, the ideals attributed to him crystallize a moment of significant transformation in the evolution of East Asian Buddhism.

His story helped to re-center Buddhism around experiential practice at a time when it risked being absorbed by ritual formalism and political utility. In doing so, Bodhidharma served as a corrective force, offering a stripped-down, intensely disciplined form of engagement with the Dharma that rejected both external display and intellectual ornamentation. His example gave voice to an approach that values the unmediated moment, the rigor of meditation, and the self-transcending nature of true insight.

Figures like Bodhidharma endure in Buddhist history not because they are unchanging monuments, but because they are reshaped and reinterpreted to meet the existential and cultural needs of each new era. They function as vessels of renewal, recurring reminders of the original promise of the path: not as a system of belief, but as a method of awakening. Bodhidharma, in this sense, is not merely a founder of Zen but a living pointer to the heart of Buddhist practice itself.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

comments