The influence of Daoism and Confucianism on Chinese Chán Buddhism

The emergence of Chán Buddhism in China was not an isolated event but the result of centuries of cultural, philosophical, and religious interaction. While rooted in Indian Buddhist traditions, particularly the Mahāyāna emphasis on emptiness (sūnyatā) and direct realization, Chán developed in a Chinese intellectual and spiritual environment shaped by Daoism and Confucianism. Among these, Daoism played a particularly significant role in shaping the tone, language, and orientation of early Chán, while Confucianism contributed more subtly, often influencing social structures and ethical concerns. In this post, we examine how these indigenous traditions influenced the development of Chán, both in its formative centuries and in its later interpretations.

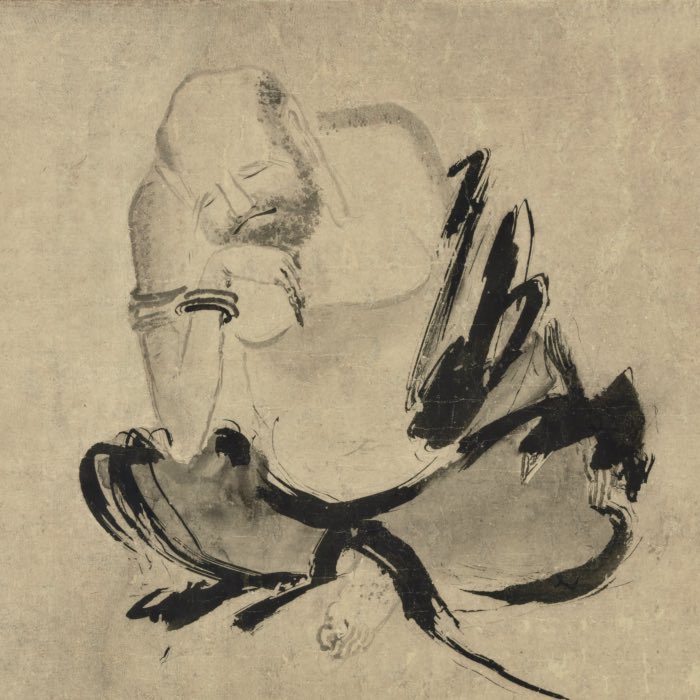

Left: Ensō (円相), a circle symbolizing enlightenment, the universe, and the void. Right: Bagua, a set of symbols intended to illustrate the nature of reality as being composed of mutually opposing forces reinforcing one another. It is a group of trigrams — composed of three lines, each either “broken” or “unbroken”, which represent yin and yang, respectively. In the center of the bagua is the taiji symbol, another representation of the concept of yin and yang. Source of the ensō: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0; modified). Source of the bagua symbol: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Historical perspective: Chán in the Chinese religious-philosophical Landscape

Chán Buddhism arose in a cultural milieu already rich with religious practices and philosophical discourse. By the time Buddhist missionaries from India arrived in China (beginning in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE), Daoism was already well established as a spiritual path concerned with harmony with the cosmos, non-action (wuwei), and the mysterious source of all being (Dao).

Initially, many Chinese translators of Indian texts drew upon Daoist terminology to render complex Buddhist concepts more intelligible. Terms like Dao for Dharma, wu for emptiness, or [ziranziran (self-so-ness) for tathatā (suchness) became part of a syncretic vocabulary. This helped Buddhism gain acceptance, but it also began to subtly reshape its interpretation.

As Chán began to take form during the 6th to 9th centuries CE, particularly through the teachings of figures like Bodhidharma, Huike, and later Huineng (638–713), Daoist modes of thought became more explicitly intertwined with Buddhist practice. Chán’s emphasis on spontaneity, naturalness, and intuitive understanding resonated deeply with Daoist aesthetics and epistemology. In contrast, Confucianism — with its emphasis on ritual, social roles, and moral cultivation — was less influential in shaping Chán practice, although it continued to play a role in shaping monastic discipline and the ethical expectations of laypeople.

Mapping Daoist influences in Chán and Zen

In the following, we compare some of core Daoist concepts with their Chán counterparts, highlighting the ways in which Daoism may have influenced the development of Chán.

The Dao and emptiness (śūnyatā)

The Daoist Dao is described in texts such as the Dao De Jing (道德經) by Laozi as a formless, ineffable, and generative principle that underlies all things. It cannot be grasped by conceptual thinking or linguistic description. This has significant parallels with the Mahāyāna Buddhist concept of śūnyatā (空), or “emptiness”, particularly as elaborated in the Prajñāpāramitā literature and later Madhyamaka philosophy (e.g., Nāgārjuna).

In Chán, especially under the influence of the Platform Sūtra attributed to Huineng (638–713) (慧能), the ineffability of the Buddha-nature and the emphasis on direct, non-conceptual realization resonate closely with the Daoist emphasis on intuitive understanding of the Dao. Both traditions critique a purely intellectual or scholastic approach to truth, yet they do so from different ontological premises: Daoist thought often gestures toward a primal unity underlying all existence, whereas Buddhist teachings deny the existence of any inherent, singular substance or ground. This distinction, while subtle, marks a critical divergence in the metaphysical orientation of the two systems.

Xu: Daoist emptiness vs. śūnyatā

A particularly nuanced comparison arises when we examine the Daoist concept of emptiness as receptivity and contrast it with the Buddhist notion of śūnyatā. In Daoist thought — especially in the Daodejing and Zhuangzi — emptiness, or Xu (虛), is portrayed not as void or absence, but as a dynamic openness, a fertile receptivity that allows all things to arise and return without resistance. It is the condition for transformation, flow, and harmony with the Dao. Metaphors such as the empty valley, the uncarved block, or the still mirror suggest a form of generative emptiness — one that holds space for life to emerge without interference.

In contrast, Mahāyāna Buddhism — especially in the Madhyamaka tradition of Nāgārjuna — conceives of śūnyatā as the absence of inherent existence (svabhāva) in all phenomena. It is not a generative metaphysical field but a critical tool: a way to see that all things arise dependently and lack any fixed essence. This insight is meant to free one from clinging to any views, identities, or realities presumed to be solid or eternal. Emptiness here is deconstructive, not affirming.

In Chán Buddhism, particularly as expressed in texts like the Platform Sūtra, we may observe both influences. There is Daoist-style receptivity in the emphasis on open awareness, spontaneous presence, and the dropping of concepts. Yet the fundamental aim remains Buddhist: not to merge with a cosmic flow, but to realize the lack of a permanent self and the interdependence of all phenomena. Thus, while Daoist Xu and Buddhist śūnyatā both reject fixed identities, they differ in tone and function — one receptive and fertile, the other analytic and liberative. This distinction, though subtle, marks a crucial divergence in how emptiness is lived, applied, and ultimately understood.

Naturalness and spontaneity (ziran)

The Daoist ideal of ziran, or “so-of-itselfness”, and fengliu, “flowing along with the current”, expresses a spontaneous mode of existence that arises naturally, without forced effort or artificial interference. This resonates deeply with Chán and Zen teachings, which often warn against striving toward enlightenment as though it were a fixed goal. Zen masters consistently emphasized that true awakening cannot be attained through willful ambition, but emerges through an effortless return to the mind’s original clarity. This orientation mirrors the Daoist vision of aligning oneself with the Dao — a flowing, dynamic order of reality that cannot be grasped or manipulated, only realized through living in accord with one’s innate nature.

Non-action (wuwei)

wuwei, or “non-doing”, is not passivity but a state of acting in seamless alignment with the spontaneous rhythms of nature. In Daoist thought, wuwei embodies the highest wisdom — effortless action that arises from attunement rather than will. This principle resonates powerfully with Chán meditation, especially in the practice of zazen or shikantaza, where one sits not to attain anything, but to embody presence itself. In this mode, there is no striving, no manipulation of thought, and no technique to perfect. Enlightenment, in this view, is not a goal to reach but an ever-present clarity that emerges when all clinging ceases. The very act of letting go becomes the path, and in this letting go, the practitioner reflects the Daoist insight that true action arises only when there is no self-centered effort.

Embrace of paradox

Daoist texts like the Daodejing frequently use paradox to express the ineffable and self-negating nature of the Dao, challenging the limitations of binary thinking and discursive logic. These paradoxes are not meant to be solved in a rational sense, but to dislodge fixed conceptual frameworks and point directly to a more intuitive grasp of reality.

Chán Buddhism, especially through its kōan literature and dialogical encounters, adopted similar strategies to provoke insight. Masters such as Zhaozhou and Yunmen used cryptic expressions, rhetorical reversals, and startling contradictions to disrupt habitual cognition. Statements like “the sound of one hand clapping”, “no mind, no Buddha”, or “ordinary mind is the Way” serve not as doctrinal propositions but as experiential catalysts. This embrace of paradox, deeply influenced by Daoist epistemology, became a hallmark of Zen training, aimed at awakening insight beyond the dualisms of subject and object, self and other, form and emptiness.

Zuowang and Zazen

One of the most compelling intersections between Daoist and Chán meditative practice lies in the potential connection between the Daoist practice of zuòwàng (坐忘, “sitting in oblivion”) and the Zen practice of zazen (坐禅, “seated meditation”). Zuowang, as described in classical Daoist texts such as the Zhuangzi, refers to a deep meditative state characterized by the erasure of personal identity, desires, and conceptual thought. It is a process of forgetting the self and returning to an undifferentiated oneness with the Dao.

Similarly, zazen, especially in its later development as shikantaza (“just sitting”), emphasizes a radical openness and non-intervention. The practitioner sits without clinging to thoughts, striving for attainment, or employing techniques. Rather than concentrating on a specific object or mantra, the focus in zazen is awareness itself — open, ungrasping, and self-emptying.

Both zuowang and zazen emphasize a letting go that transcends dualistic consciousness. Yet, important differences underlie their surface resemblance. Zuowang is grounded in a Daoist metaphysics that aims for alignment with the Dao — a return to primordial unity through effortless surrender. In contrast, zazen as understood in Chán arises from the Buddhist framework of śūnyatā and non-self (anatta), aiming not at merger with a cosmic source, but at insight into the empty and interdependent nature of all phenomena. The practitioner is not returning to a metaphysical oneness but awakening to the absence of inherent existence.

Thus, while it is plausible that Chinese Buddhists immersed in Daoist discourse drew upon the ethos of zuowang in developing indigenous meditative forms, the philosophical intentions and soteriological aims diverge. This distinction helps preserve the unique identity of Chán as a Buddhist path, even as it reveals its openness to cultural resonance

Syncretic textual and cultural transmission

During the early medieval period (3rd–6th centuries CE), Buddhism in China engaged deeply with Daoist terminology in order to render Indian concepts accessible to a Chinese audience steeped in indigenous philosophical and cosmological frameworks. This was not a simple translation effort, but a complex cultural negotiation.

Dao was often used to translate key Buddhist concepts such as Dharma or Bodhi, imbuing them with connotations of cosmic principle and harmony. The Daoist concept of the unnamable source of all being resonated with the Buddhist idea of emptiness (śūnyatā), and this resonance shaped how Chinese readers came to understand Buddhist metaphysics.

Cosmological structures, such as the interplay of yin and yang or the cycles of transformation, further influenced the Chinese reception of ideas about mind, consciousness, and dependent origination. Chinese translators like Kumārajīva occasionally employed Daoist metaphors and terms in their efforts to transmit the Buddha’s teachings, helping to align Buddhist teachings with a Daoist sense of intuitive, flowing naturalness.

This process led to more than a convergence of vocabulary. It cultivated a shared conceptual universe in which Daoist and Buddhist worldviews could coexist, interact, and mutually reinforce one another. The result was not a diluted Buddhism, but a distinctly Chinese form of Buddhism — Chán — rooted in translation, adaptation, and transformation.

Anti-intellectualism and critique of language

Both Daoist and Chán traditions emphasize the limitations of language and conceptual knowledge, warning against the illusion that truth can be fully expressed through words. The Daoist maxim “the Dao that can be spoken is not the eternal Dao” encapsulates a perspective that sees language as inherently limited, prone to fixating on names and concepts rather than pointing to lived reality. Especially in the Zhuangzi (莊子), this critique becomes a rich literary and philosophical practice: Zhuangzi uses paradox, wordplay, and absurdity to expose the artificiality of conventional distinctions and the futility of rigid logic. These strategies are not intended to convey doctrine but to unsettle habitual thinking and evoke a spontaneous, holistic awareness.

Chán Buddhism inherits and adapts these methods. Its preference for silence, gesture, or non-verbal communication aligns with the Daoist critique, but it also introduced distinctive pedagogical tools such as gong’an (公案, kōan in Japanese) — paradoxical questions or narratives used to break the student’s dependence on rational analysis. Like Zhuangzi’s playful dialogues, koans serve to interrupt the grasping mind and nudge the practitioner toward direct insight. Closely related is the emphasis on “no-mind” (wuxin, 無心) or “no-thought” (wunian, 無念), which mirrors the Daoist principle of wuwei (無為), or non-striving. Rather than suppressing cognition, Chán encourages a form of awareness that is open, fluid, and unattached — a consciousness not fixated on objects, including the idea of enlightenment itself.

This mutual suspicion of linguistic formulation fostered a shared emphasis on wordless teaching and embodied practice, where pointing at the moon is never to be confused with the moon itself.

Rejection of formalism and ritualism

Early Daoism is often portrayed as skeptical of formal ritual and codified religion, emphasizing instead a return to an original simplicity grounded in harmony with the Dao rather than compliance with prescribed rites. This skepticism toward institutionalized spirituality resonated with early Chán’s own departure from Indian Buddhist orthodoxy.

While early Indian Buddhism was highly monastic and rule-bound (Vinaya), Chán in China developed a more relaxed and flexible attitude toward ritual, liturgy, and scriptural study. Monastic discipline remained, but it was no longer the exclusive vehicle of liberation. Instead, Chán emphasized:

- Meditation as the primary path — though reinterpreted not as concentrative samādhi, but as an open, non-dual awareness interwoven with daily life,

- Direct transmission outside scriptures (jiaowai biechuan, 教外別傳), bypassing scholastic study in favor of lived realization,

- “A special transmission beyond the teachings” — a phrase that encapsulates Chán’s mistrust of textualism and its faith in direct, embodied wisdom.

This shift did not result in a wholesale rejection of ritual or doctrine but rather a repositioning of them as supportive, not central. Much like Daoism, Chán advocated for insight that emerges through immediacy, simplicity, and a freedom from over-intellectualized forms of religiosity.

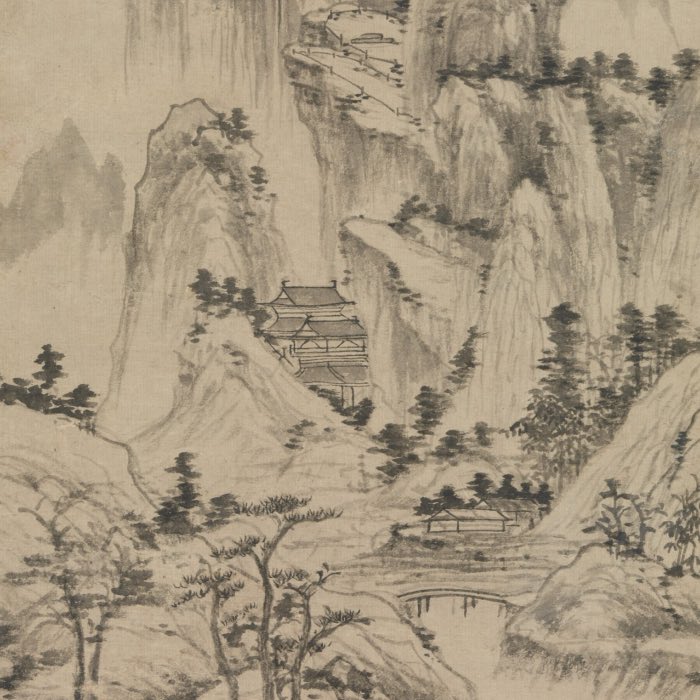

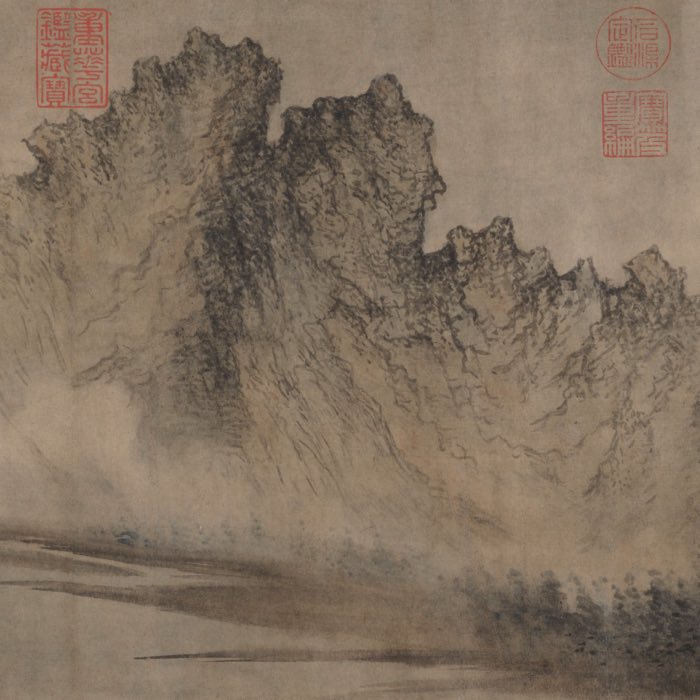

Aesthetic simplicity and harmony

Zen arts such as ink painting, calligraphy, tea ceremony, and garden design reflect a deeply ingrained Daoist aesthetic that values spontaneity, subtlety, and the transient beauty of imperfection (see., e.g., Pu, the Daoist concept of simplicity, fengliu, “flowing along with the current”, ziran, naturalness and spontaneity). These artistic expressions are not merely cultural byproducts but are themselves forms of contemplative practice — extensions of the Zen worldview where every brushstroke, gesture, or arrangement becomes a direct enactment of meditative insight. Emptiness in the brushstroke, the quiet pause of a tea ritual, or the asymmetrical composition of a rock garden are not decorative choices; they mirror the Daoist principle of harmony with the formless, the ungraspable. In this sense, Zen aesthetics are not only shaped by Daoist sensibilities but also function as an embodied philosophy that reveals rather than represents the nature of reality.

Daoism, Chán, and the question of syncretism

The undeniable resonance between Daoism and Chán raises a provocative question: is Chán merely a hybrid of Indian Buddhism and Chinese Daoism? Some scholars and critics — such as Tang Yongtong, Chen Yinke, and Peter Gregory — have argued that what emerged as Chán is less a continuation of Indian Mahāyāna and more a reformulation shaped by Daoist metaphysics and Chinese cultural norms. The emphasis on spontaneity, the critique of scripture, and the valorization of direct experience all seem more Daoist than Buddhist in origin.

Yet such a view may miss the dynamic and dialogical nature of Chán. Rather than a passive merger or dilution, Chán represents a uniquely Chinese response to Indian Buddhism — a transformation that honors its roots while adapting to a new cultural soil. Chán is neither “pure” Buddhism nor disguised Daoism, but an evolving tradition that exemplifies its own core insight: that truth is not static, and awakening must meet conditions as they are. Its ability to absorb, reformulate, and challenge is not a weakness, but its defining strength.

Caution against overstated parallels

While the structural and conceptual resonances between Daoism and Chán Buddhism are undeniable and have been extensively documented, we must remain cautious about assuming direct equivalences or mutual derivation where only superficial similarity exists. In one of our previous posts we have discussed the phenomenon of parallelomania, which refers to the tendency to overemphasize connections between traditions based on perceived likeness, while overlooking important contextual, doctrinal, and methodological distinctions.

For example, while ziran (spontaneity) and wu wei (non-doing) appear to align closely with Chán’s advocacy of effortless meditation or non-striving, the ontological assumptions underpinning these ideas differ. The Daoist cosmology often implies an original harmony to return to, a kind of primordial oneness, whereas in Buddhism — especially under the influence of śūnyatā — there is no such foundational unity. Rather than all things emerging from a single cosmic source, as in Daoism, Buddhist teachings emphasize the lack of inherent existence and the interdependent co-arising of phenomena. This view rules out any pantheistic or essentialist metaphysics.

Likewise, although zuowang (sitting in oblivion) and zazen (seated meditation) may appear superficially similar, they differ substantially in intent and philosophical backdrop. Zuowang aims at a return to the Dao through effacement of the ego and merging with the primordial source, while zazen — especially in the form of shikantaza — focuses on the realization of emptiness and the non-substantial nature of the self and all phenomena. There is no Dao to merge with, but rather a clear seeing into the lack of any abiding substance whatsoever.

Similarly, the Daoist emphasis on cosmic flow does not carry the ethical or soteriological structure that Buddhist liberation presupposes, such as the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path. Buddhist awakening is not merely intuitive or aesthetic attunement to the cosmos but involves ethical conduct, mindfulness, and wisdom as integral components of the path.

Recognizing affinities should not obscure the uniqueness of each tradition. Chán’s distinctive synthesis emerged from a particular historical process of translation, reinterpretation, and embodied practice, not merely from philosophical borrowing. What makes Chán compelling is not that it mirrors Daoism, but that it responds to its presence while still remaining fundamentally Buddhist.

Conclusion

The influence of Daoism — and to a lesser extent, Confucianism — on the development of Chán Buddhism in China reveals a rich interplay between indigenous Chinese thought and Indian Buddhist principles. While deeply grounded in the Mahāyāna tradition of emptiness, non-self, and dependent origination, Chán may have adopted and reinterpreted key Chinese values such as [ziranziran (spontaneity), wuwei (non-doing), and the Daoist critique of language and form. These resonances helped shape a distinctly Chinese form of Buddhist practice — one that favored intuition over analysis, wordless insight over discursive knowledge, and immediacy over doctrinal abstraction. They also facilitated the communication of Buddhist principles in a conceptual language already familiar to the Chinese audience, allowing abstract teachings like emptiness, non-self, and dependent origination to be rendered more intelligible through Daoist metaphors and imagery.

Daoist aesthetics and epistemology may have influenced the Chán approach to pedagogy and expression, manifesting in its paradoxical dialogues, its embrace of silence, and its use of kōans. Meanwhile, Confucian values appear to have played a more structural role, potentially informing monastic ethics and social relationships without necessarily penetrating the doctrinal or soteriological core.

Yet these affinities must not obscure foundational differences. Daoism and Chán may converge on certain stylistic and epistemological fronts, but their metaphysical commitments diverge significantly. The Dao as an original cosmic unity stands in contrast to the Buddhist rejection of inherent existence. Concepts such as zuowang and zazen, while outwardly similar, emerge from and point toward different understandings of the self and liberation. Buddhist liberation is not a return to a primordial oneness but a radical awakening to the insubstantial, interdependent nature of all things.

After comparing traditions and our above analysis, I come to the conclusion that rather than a Daoist rebranding of Buddhism, Chán may be better understood as a demonstration of Buddhism’s dynamic capacity to absorb and reframe its environment. It is not a hybrid but a transformation — fully Buddhist in aim and method, yet unmistakably shaped by Chinese cultural sensibilities. This flexibility is not a deviation from the Dharma but an expression of its depth.

What continues to make Chán so philosophically provocative and spiritually resonant is precisely its refusal to become rigid. By sharpening rather than dissolving its distinctions with other traditions, Chán has emerged as a powerful, adaptive expression of Buddhist thought. It remains a path of awakening rooted in the conditions of its time, yet open to the boundless possibility of insight here and now.

References and further reading

- Chun-chieh Huang, The debate and confluence between Confucianism and Buddhism in East Asia, 2019, V&R unipress, ISBN: 978-3847110385

- Gregory, Peter N., Sudden and Gradual: Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought, 2024, Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House, ISBN: 978-9359719580

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

comments