The role of compassion and loving-kindness in Buddhism

Compassion, or karuṇā, occupies a prominent position within Buddhist thought and practice. It is regarded not simply as an emotion, but as a cultivated disposition toward relieving the suffering of others. Unlike empathy, which involves resonating with another’s pain, Buddhist compassion is seen as an active and intentional commitment to alleviate suffering. It is often discussed in conjunction with related concepts such as mettā (loving-kindness), anattā (non-self), and bodhicitta (the aspiration toward awakening for the benefit of others), and is considered instrumental in the development of moral conduct (sīla) and insight (prajñā). In this post, we explore the role of compassion in Buddhism, its philosophical underpinnings, and its practical implications.

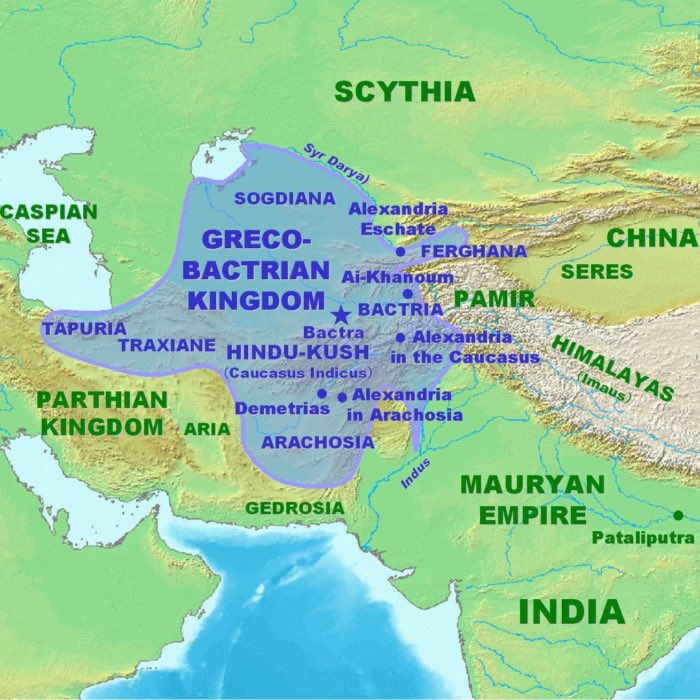

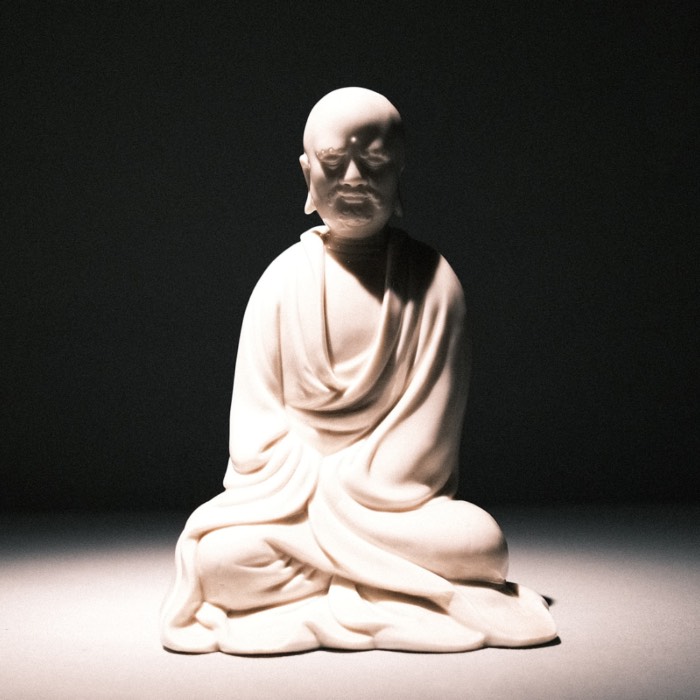

Standing Bodhisattva, Gandhara (present-day Pakistan), 2nd - 3rd century CE, schist. This Gandharan sculpture represents a Bodhisattva — an enlightened being in Mahayana Buddhism who embodies the ideal of compassion by forgoing personal liberation to assist others. The figure’s youthful features, adorned garments, and meditative expression reflect both worldly refinement and spiritual aspiration. Elements such as the uṣṇīṣa (topknot), ūrṇā (dot on the forehead), and halo signal its symbolic role in visualizing the path of compassionate engagement within Buddhist traditions. Exhibited at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, 2023.

Standing Bodhisattva, Gandhara (present-day Pakistan), 2nd - 3rd century CE, schist. This Gandharan sculpture represents a Bodhisattva — an enlightened being in Mahayana Buddhism who embodies the ideal of compassion by forgoing personal liberation to assist others. The figure’s youthful features, adorned garments, and meditative expression reflect both worldly refinement and spiritual aspiration. Elements such as the uṣṇīṣa (topknot), ūrṇā (dot on the forehead), and halo signal its symbolic role in visualizing the path of compassionate engagement within Buddhist traditions. Exhibited at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, 2023.

Compassion as a response to suffering

At the core of Buddhist doctrine is the recognition of suffering (dukkha) as a pervasive aspect of existence. This premise is encapsulated in the first of the Four Noble Truths. Within this framework, the cultivation of compassion emerges as a logical and ethical response to the universality of suffering. Compassion is intended to extend beyond the human domain to encompass all sentient beings, reflecting the Buddhist emphasis on interdependence and the continuity of life across perceived boundaries.

In Mahayana Buddhism, the figure of the bodhisattva represents the ideal of someone who renounces immediate personal liberation in order to assist others in attaining it. This ideal functions as a model for expressing compassion not as an isolated virtue but as a guiding principle of the Mahayana path. The bodhisattva ethic highlights the centrality of compassion as integral to the pursuit of enlightenment, rather than a secondary or optional element.

Historically, the concepts of karuṇā and mettā appear in the early Pāli texts, which are among the earliest recorded Buddhist scriptures. The more elaborated ideal of bodhicitta (a central Mahayana Buddhist concept that refers to the altruistic intention to achieve enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings) and specific practices like tonglen (a Tibetan Buddhist meditation in which the practitioner visualizes taking in the suffering of others on the in-breath and sending out relief and happiness on the out-breath, thereby cultivating selflessness and empathetic responsiveness) emerge later, particularly in Mahayana and Tibetan traditions. This development reflects a broadening and deepening of the compassion concept as Buddhism evolved across cultural and historical contexts.

Compassion and the doctrine of non-self (anattā)

A distinctive aspect of Buddhist philosophy is the doctrine of anattā, which denies the existence of a permanent, autonomous self. According to this perspective, the boundaries between individuals are constructs rather than inherent realities. This ontological stance has ethical consequences: by deconstructing the self-other dichotomy, it becomes plausible to regard another’s suffering as not fundamentally separate from one’s own. In this way, compassion is presented not merely as a moral virtue but as a logical extension of insight into the nature of existence.

This contrasts with many Western conceptions of charity, which often maintain a clear distinction between the giver and the recipient. Buddhist compassion tends to operate within a framework of interdependence, emphasizing mutual transformation rather than unilateral beneficence. Alleviating another’s suffering is thus framed as intimately connected with one’s own spiritual progress.

From a comparative perspective, compassion in Buddhism shares certain affinities with concepts such as Christian agape or Stoic cosmopolitanism, which also advocate universal concern. However, the underlying metaphysical assumptions differ significantly. Whereas Christian agape is grounded in divine love, Buddhist compassion arises from a non-theistic understanding of impermanence and interconnectedness. These divergent metaphysical foundations lead to distinct modes of cultivating and expressing compassion: where Christian agape may emphasize divine grace and moral duty, Buddhist compassion emerges from contemplative insight into interdependence and the non-self. As a result, Buddhism promotes specific psychological and meditative techniques designed to systematically dismantle egocentric views and foster an unconditional, equanimous attitude toward all beings. The justification for compassion thus shifts from obedience to a moral authority to a transformative understanding of reality itself.

Cultivating compassion: Karuṇā Bhāvanā and other practices

The development of compassion is pursued through structured meditative exercises, particularly in the form of karuṇā bhāvanā, or compassion meditation. Practitioners are instructed to gradually expand their circle of compassion, beginning with themselves and progressing to friends, neutral individuals, and even antagonists. This methodical expansion reflects a deliberate attempt to neutralize partiality and deepen emotional equanimity.

In Tibetan Buddhist traditions, the practice of tonglen involves visualizing the inhalation of others’ suffering and the exhalation of relief and happiness. Such practices are interpreted as both psychological and ethical training, designed to undermine habitual self-centeredness and reinforce pro-social attitudes.

Modern psychological studies have, for instance, documented that compassion training modeled on Buddhist practices — such as mettā or loving-kindness meditation — can increase positive affect, reduce implicit bias, and enhance resilience and prosocial behavior (e.g., Fredrickson et al., 2008; Hofmann et al., 2011; Kirby, Tellegen & Steindl, 2017). These studies suggest that shown that compassion training based on Buddhist techniques may have measurable effects on emotional regulation, empathic concern, and overall well-being. Secular adaptations of practices like mettā meditation are now incorporated into mindfulness-based therapies, including programs for stress reduction and trauma recovery. This suggests that the psychological mechanisms cultivated in traditional Buddhist compassion exercises — such as the attenuation of self-focus, increased emotional regulation, and enhanced perspective-taking — may be functionally effective even outside a religious framework. Their integration into secular mindfulness-based therapies implies a broader applicability that aligns ancient meditative disciplines with contemporary mental health paradigms, thereby bridging contemplative traditions and scientific empiricism.

The interdependence of wisdom (prajñā) and compassion (karuṇā)

Buddhist literature frequently presents compassion and wisdom as mutually reinforcing. Compassion without insight may result in emotional exhaustion or ineffective altruism, while insight without compassion risks becoming detached or indifferent. The integration of both is viewed as essential to the ideal of full awakening.

In the context of Zen Buddhism, this integration is expressed through the emphasis on immediate, embodied action. The Zen approach tends to eschew elaborate visualizations in favor of spontaneous and practical responses to suffering. The oft-cited expression “a bodhisattva’s work is in the kitchen” reflects the belief that compassion is realized through mundane acts, not only through formal spiritual exercises.

Ethical and social implications

While often cultivated through introspective methods, compassion in Buddhist traditions is expected to manifest outwardly in ethical behavior. The moral precepts (sīla) promoted in various schools of Buddhism — such as non-harming (ahiṁsā), truthfulness, and right livelihood — are seen as practical expressions of a compassionate orientation.

Another foundational expression of compassion in Buddhist ethics is dāna, or the practice of generosity. As one of the primary perfections (pāramitās), dāna reflects the enactment of compassion through the voluntary sharing of material goods, time, energy, or protection. It functions not only as an ethical gesture but also as a method for loosening attachment and overcoming self-centeredness. Historically, dāna has structured relationships between monastic (sangha) and lay communities, forming an economy of reciprocal care that emphasizes mutual support and interdependence.

Historical examples indicate that these ideals have also found social and political expression. The Indian emperor Ashoka, who ruled in the third century BCE and publicly embraced Buddhist principles, implemented policies that emphasized non-violence and welfare. In more recent times, figures like Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh have combined Buddhist ethics with activism, particularly in contexts of war and ecological degradation.

Conclusion

Buddhist teachings on compassion, as observed across historical and doctrinal developments, present a multifaceted concept that intertwines ethical commitment, meditative cultivation, and philosophical insight. Compassion is not regarded merely as an emotional inclination but as a deliberate practice rooted in the understanding of suffering, the non-existence of a fixed self, and the interdependence of all beings. It serves both as a personal discipline and as a foundation for broader ethical and even political action.

What distinguishes the Buddhist approach is the integration of compassion with ontological principles such as anattā and impermanence, which deconstruct self-other boundaries and frame altruism as a natural consequence of insight rather than divine command or social obligation. Unlike in many Western traditions where compassion may be conceptualized within dualistic or theistic paradigms (such as Christian agape or Kantian duty), Buddhist compassion is rooted in non-theism and a relational metaphysics. This gives rise to practices that are not only introspective but also systematically designed to reduce egocentrism, as evidenced in methods like karuṇā bhāvanā and tonglen.

Modern psychological research has begun to validate the benefits of these practices in secular terms, suggesting a convergence between ancient contemplative traditions and contemporary mental health approaches. Yet, one might critically ask whether Buddhist compassion, with its emphasis on equanimity and detachment from self-centered desires, might risk emotional disengagement or inadequacy in the face of structural injustices that demand confrontation rather than inward transformation.

Nevertheless, Buddhism offers a compelling framework for addressing suffering at both the personal and systemic levels. Its strengths lie in its consistency between theory and practice, its scalable tools for cultivating prosocial behavior, and its philosophical coherence in linking compassion to an overarching view of reality. In this sense, Buddhism arguably provides a more integrative and psychologically sustainable model of compassion than many of its Western counterparts.

References and further readings

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Fredrickson, Barbara L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. 2008, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1045–1062. DOI: 10.1037/a0013262ꜛ

- Hofmann, S. G., Grossman, P., & Hinton, D. E. Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: Potential for psychological interventions. 2011, Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1126–1132. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.003ꜛ

- Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Steindl, S. R. A meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: Current state of knowledge and future directions. 2017, Behavior Therapy, 48(6), 778–792. DOI: 10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003ꜛ

- Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Karuna, Zen und der Weg der tätigen Liebe, Der Bodhisattva-Pfad im Buddhismus und im Zen, 1. Januar 1996

comments