Karma and Samsara in Indian thought and Siddhartha’s revolutionary reinterpretation

Among the many contributions of Siddhartha Gautama to the Indian religious and philosophical landscape, his reconceptualization of karma and samsara stands out as one of the most radical. While these notions were already central to the spiritual worldview of his time, his reframing of them challenged deeply entrenched metaphysical assumptions and proposed a psychological and ethical framework that redefined what it means to be liberated. In this post, we explore the historical and doctrinal context of karma and samsara in Indian thought, and how Siddhartha’s reinterpretation transformed these concepts into a practical guide for understanding suffering and achieving liberation.

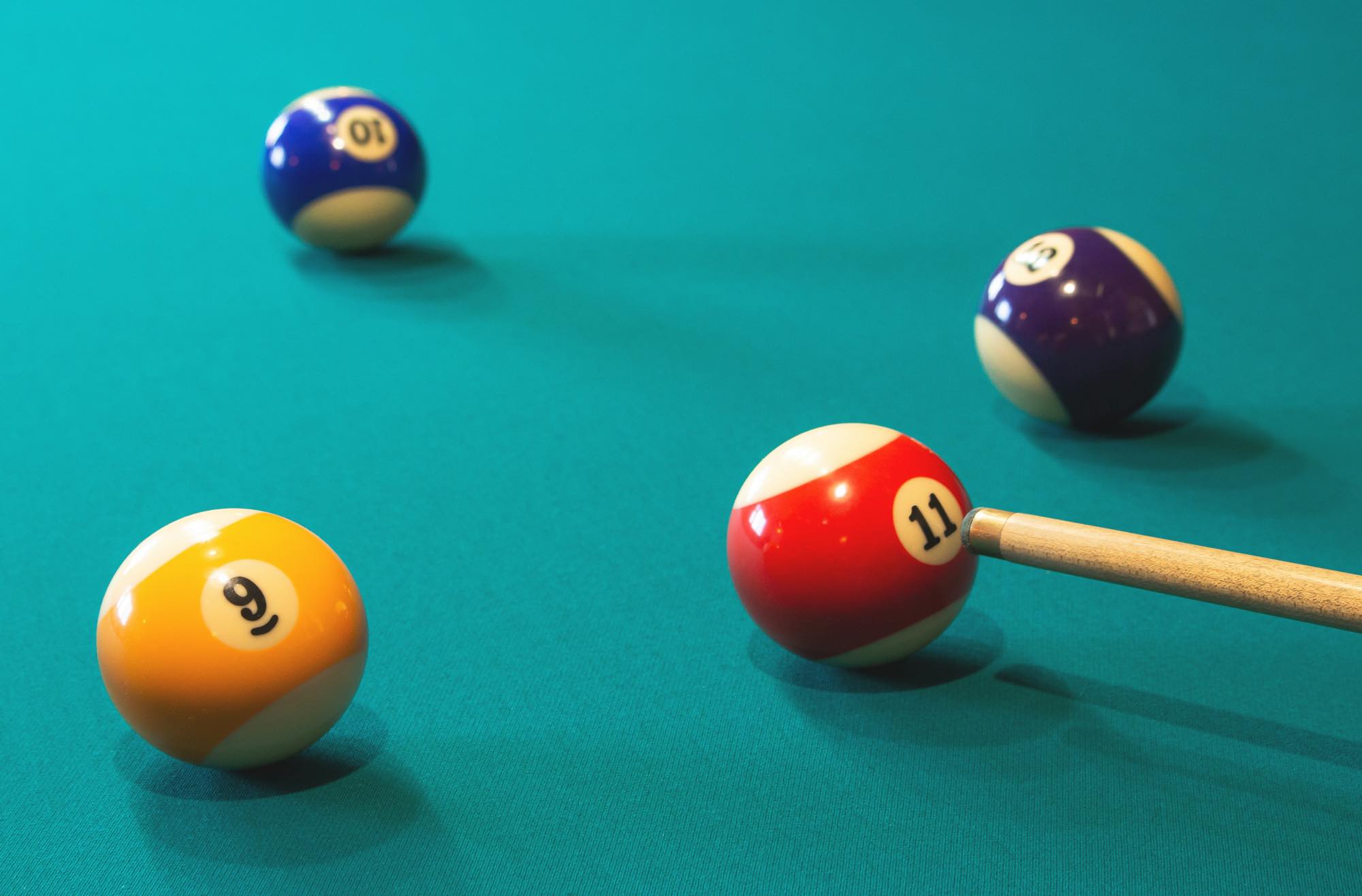

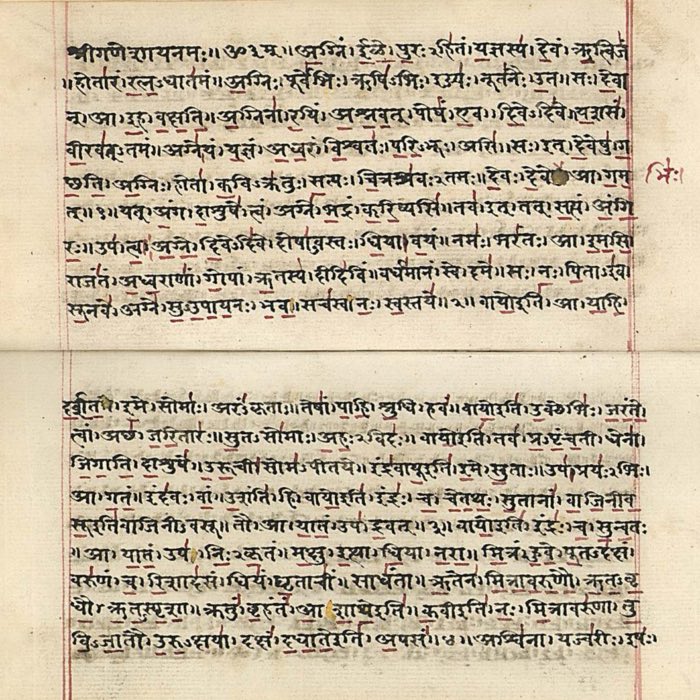

In early Indian thought, karma governed the rebirth of a self through countless lifetimes. Siddhartha Gautama replaced this view with a dynamic model of causality: like billiard balls colliding, one volitional act gives rise to the next moment of experience, without the need for a permanent soul. Samsara, in this light, is not a cosmic cycle we are trapped in, but a psychological process we continuously enact — and can interrupt. Source: Katherine Krombergꜛ on Unsplashꜛ (license: Unsplash Licenseꜛ).

In early Indian thought, karma governed the rebirth of a self through countless lifetimes. Siddhartha Gautama replaced this view with a dynamic model of causality: like billiard balls colliding, one volitional act gives rise to the next moment of experience, without the need for a permanent soul. Samsara, in this light, is not a cosmic cycle we are trapped in, but a psychological process we continuously enact — and can interrupt. Source: Katherine Krombergꜛ on Unsplashꜛ (license: Unsplash Licenseꜛ).

The conventional view: Karma and rebirth in Indian tradition

Prior to the emergence of Buddhist thought, Indian religious and philosophical traditions had already developed rich and systematic accounts of moral causality, rebirth, and liberation. These views were deeply embedded in both metaphysical assumptions and social structures, forming a shared conceptual framework that shaped how existence, suffering, and transcendence were understood.

Karma as moral causality and social logic

Before the emergence of Siddhartha Gautama, Indian religious traditions — especially those shaped by early Vedic thought and later Brahmanical orthodoxy — had developed elaborate doctrines of karma and rebirth. Karma (from Sanskrit karman, meaning “act” or “deed”) referred to the causal law by which intentional actions — physical, verbal, and mental — produce consequences that shape future existence. Far from being an abstract metaphysical idea, karma functioned as a pervasive moral law that shaped the unfolding of a person’s life across multiple incarnations.

Within this framework, good actions — those aligned with dharma (duty), truthfulness, and ritual purity — were thought to generate positive karmic residue, leading to favorable rebirths. Conversely, harmful or selfish actions yielded negative karma, resulting in suffering either in this life or the next. Karma thus served not only as a metaphysical principle but also as a practical moral engine, embedded within the broader cosmic order and social structure.

This system provided a theological basis for the caste hierarchy. An individual’s social status — whether born into poverty, privilege, health, illness, or spiritual authority — was interpreted as the just result of past actions. For example, a prosperous merchant might regard his success as the karmic fruit of previous virtue, while a laborer suffering chronic misfortune might be counseled to accept his condition as retribution for prior misconduct. Such interpretations not only informed personal conduct but also reinforced the broader social order by sacralizing inequality.

Samsara: The cycle of suffering and becoming

Within this traditional worldview, samsara denoted the continuous cycle of birth, death, and rebirth that all sentient beings undergo. It was not simply a series of individual lives, but the very condition of worldly existence — defined by impermanence (anitya), ignorance (avidyā), and suffering (dukkha). Crucially, samsara was governed by moral causality: every intentional action generated karmic consequences, binding the individual to further cycles of becoming.

This process presupposed the existence of a persistent, transmigrating self (ātman) that accrued the effects of karma across lifetimes. Rebirth was not metaphorical but literal, involving transitions through a hierarchically structured cosmology of realms: heavenly abodes of the devas, the human world, the animal realm, the domain of hungry ghosts (preta), and numerous hells (naraka). These were not symbolic categories but ontologically real domains, understood as direct outcomes of karmic merit or demerit.

Thus, samsara served both as a cosmological map and an ethical mechanism. It explained the apparent disparities of fortune and status while incentivizing virtuous conduct. Yet it was also inherently unsatisfactory. Even the most exalted rebirths remained entangled in a cycle marked by decay, loss, and repetition. As such, the ultimate goal was not to secure a better rebirth, but to escape the cycle altogether. This soteriological aim was framed in terms of moksha, liberation from conditioned existence.

Moksha and the orthodox Brahmanical path

In the Brahmanical tradition, liberation (moksha) was conceived as the realization of the self’s (ātman) unity with Brahman, the absolute ground of being. This required a multi-faceted path: adherence to caste-specific duties (varṇāśrama-dharma), performance of Vedic rituals, cultivation of moral virtue, and, in more speculative schools such as Vedānta, attainment of metaphysical insight.

The means to liberation thus ranged from ritual purity and sacrificial offerings to meditative contemplation and philosophical inquiry. In all cases, however, the assumption of an enduring self remained central. The ātman was seen as eternal, unchanging, and the true subject of liberation — distinct from the body and mind, yet burdened by the consequences of embodied existence.

This vision of moksha as the final emancipation of the ātman, achieved through spiritual refinement and alignment with cosmic law, was widely accepted in orthodox circles. Yet it would be precisely this metaphysical premise that would come under radical scrutiny in the emerging counter-traditions.

Śramaṇa traditions: Renunciation, determinism, and radical ethics

Parallel to the Brahmanical orthodoxy, the Indian religious landscape was marked by a wide array of renunciant movements, collectively known as the Śramaṇa traditions. These schools rejected the authority of the Vedas and offered alternative visions of liberation, often emphasizing personal discipline, asceticism, and direct experiential insight.

Jain thinkers, for example, posited the existence of an eternal soul (jīva) burdened by karmic particles. Liberation was attained through extreme non-violence (ahiṃsā), self-mortification, and the elimination of karmic influx. In contrast, the Ājīvikas adhered to a deterministic cosmology in which individual agency was illusory; liberation would occur through the inexorable unfolding of fate, not personal effort.

Other Śramaṇa schools advocated various forms of yogic detachment, meditative absorption, or epistemic restraint aimed at severing the passions that perpetuate karmic bondage. Despite their differences, all these traditions shared the fundamental conviction that samsara was a condition of suffering, and that liberation entailed the cessation of karmic reactivity.

Still, these paths operated within a shared metaphysical horizon: the existence of a transmigrating self or soul that served as the bearer of karma and the subject of liberation. None had yet mounted a fundamental challenge to the assumption that something enduring persisted through the cycle of rebirth.

Siddhartha Gautama and the challenge to metaphysical orthodoxy

By the time of Siddhartha Gautama, Indian spiritual discourse was thus marked by intense debate over the nature of samsara and the means of liberation. Competing schools had refined intricate soteriologies, each with its own view on ethics, cosmology, and meditative practice. But they remained united by a shared metaphysical foundation: the belief in a permanent self as the subject of rebirth and liberation. It was this very assumption that Siddhartha would radically reject, as we will see in the next section.

The Buddhist turn: Conditioned arising and dukkha

Siddhartha Gautama rejected the metaphysical notion of an eternal, unchanging soul that transmigrates through lifetimes. Instead of positing a continuous self that links successive rebirths, he introduced the concept of pratītyasamutpāda (dependent or conditioned arising), a central teaching that explains existence not through substance but through causality. In this model, samsara is not a metaphysical cycle involving a soul, but a dynamic, conditioned process — a chain of causally connected phenomena in which suffering (dukkha) is perpetuated by ignorance (avidyā) and craving (taṇhā).

Dependent origination describes a twelve-fold cycle in which each link arises in dependence on the preceding one. The chain begins with ignorance (avijjā), which conditions volitional formations (saṅkhārā), a term referring to intentional actions — in other words, karma in its most essential form. As stated in AN (Aṅguttara Nikāya) 6.63:

Intention is what I call karma. For having developed an intention, one acts with the body, speech and mind.

For Siddhartha Gautama, the karmic effects of an action are thus primarily determined by its underlying intention (cetana). Actions are always intentional to some degree, and it is the quality and orientation of this intention — not merely the physical or verbal act — that determine whether karmic consequences are wholesome or unwholesome. These karmic formations shape the arising of consciousness (viññāṇa), which, in turn, gives rise to name-and-form, and so on. Importantly, karma appears again later in the chain as bhava (becoming), the tenth link (more precisely: bhava is not identical with karma but refers to the phase in which karma becomes existentially efficacious, shaping the mode of future existence). Here, it denotes the karmic energy that conditions a new mode of existence, culminating in jāti (birth). Thus, karma functions both at the point of volitional intent and at the point where its effects ripen into a new existence.

This cyclical process is not like a pearl necklace where a soul is threaded through lives. Instead, it resembles a game of billiards: one ball (action) strikes another, setting off a chain reaction. The only thing that truly exists are phases within a continuous, indivisible process — not a fixed self or an entity that moves between lives. The resulting new life is not the reincarnation of a self but the causal consequence of prior conditions. There is no transmigrating subject, only the continuity of causation.

Liberation (nirvāṇa) in this view means breaking this causal chain by eliminating its primary conditions — ignorance and craving. When these are removed, volitional formations cease, and with them the entire machinery of samsaric becoming. In this sense, karma is not an external force but the operational instance of conditionality itself: it is both the product of ignorance and the engine of continued becoming. Dependent origination offers not a metaphysical explanation but a structural, phenomenological analysis of how existence arises and is experienced. It maps the arising of suffering through interdependent mental and existential conditions, revealing how ignorance, craving, and volitional formations shape the stream of lived experience. As such, it is not an abstract cosmological theory, but a practical and experiential model — one that can be directly observed in meditative introspection and dismantled through insight.

Samsara as the stream of personality

From my personal perspective, samsara can be reinterpreted not as a cosmic cycle of physical birth and death across multiple lifetimes, but as the ongoing, moment-to-moment emergence and dissolution of personality. This reinterpretation finds support in early Buddhist texts such as the Saṃyutta Nikāya and Aṅguttara Nikāya, where the Buddha speaks of the arising and cessation of dukkha not only across lifetimes but also “in this very body, in this very life” (e.g., SN 12.2). This suggests that the cycle of becoming (bhava) and rebirth (jāti) can be understood as referring not solely to literal lifetimes, but to the continuous, conditioned emergence of subjective experience and constructed identity, moment by moment.

This stands in contrast to the traditional view, which presents samsara as a morally structured cosmology involving rebirth across multiple realms, governed by karma — yet without invoking a permanent self or soul. In my understanding, what is “reborn” is not a soul or a fixed self, but the psychological construct of personality — composed of the five skandhas (form, feeling, perception, mental formations, and consciousness) — arising continuously from conditioned processes and impressions stored in the ālayavijñāna (the ‘storehouse consciousness’ posited in the Yogācāra tradition as the repository of karmic imprints).

Each moment of conscious experience can be seen as a new ‘birth’ of the self, and each moment of cessation as a ‘death’. This personality, or what might conventionally be called a pudgala, is not an enduring entity but a transient, causally constructed process — constantly formed and reformed through habitual reactions, sensory input, and mental proliferation. This view resonates with the Abhidhamma account of mind as a stream of discrete consciousness-moments (citta-vīthi), each conditioned by kamma and devoid of any underlying substance. What persists is not a self, but a succession of causally linked mental events — each moment arising, performing its function, and dissolving1. This framing is consistent with the doctrines of impermanence (anicca) and non-self (anatta), but renders them directly observable within the immediacy of lived experience rather than projecting them into a cosmological narrative.

Within this interpretation, karma is not merely the determinant of future incarnations but the very mechanism by which the illusion of personal continuity is sustained. Mental, verbal, and physical actions — particularly those driven by ignorance and craving — give rise to volitional formations that condition the next instance of identity. This means that samsara is not something we are reborn into at some later time, but something we continually participate in and reconstruct from moment to moment. It is a recursive loop of karmic becoming — a self-perpetuating process of conditioned identity-formation, not a metaphysical voyage.

This view does not reject the causal structure outlined by Siddhartha Gautama but internalizes it. The twelve links of dependent origination, rather than being interpreted solely as a model for literal rebirth, also map the cyclical dynamics of subjective experience. In this light, liberation is not the cessation of cosmic rebirth per se, but the cessation of the habitual karmic processes that perpetuate the illusion of a self. Why would one seek to end this cycle? Because it inevitably leads to dukkha — not just in the form of suffering in a specific life, but as a structural feature of existence conditioned by ignorance, craving, and clinging. As long as this cycle continues, dissatisfaction and unrest will persist. The end of samsara is thus the end of this perpetuated suffering. Samsara ends when we cease to construct the conditions that give rise to it.

Karma and the illusion of self

One common objection raised against the Buddhist view of karma and non-self (anatta) is that they seem logically incompatible: if there is no enduring self, how can one individual experience the consequences of actions committed by another? Wouldn’t karmic retribution be unfair — punishing someone other than the person who acted? This line of thought assumes that karma operates as a moral system of reward and punishment assigned to a stable subject. But in early Buddhist thought, karma is not a mechanism of retribution, nor is it based on the assumption of responsibility grounded in a continuous self. Rather, karma simply describes the unfolding of causal processes: when certain actions are performed, certain consequences follow — not as punishment or reward, but as conditioned results.

This becomes especially clear in MN (Majjhima Nikāya) 135, where Siddhartha Gautama declares:

Beings are owners of their actions (karma), heirs of their actions; they originate from their actions, are bound to their actions, and have their actions as their refuge.

The term karma here refers both to the process and to its cumulative result. The continuity of the so-called person is not metaphysical, but functional: it consists in the causal sequence of events that are linked by volitional activity and intention. The illusion of a stable self arises precisely because these events are causally connected.

A similar insight is articulated in the Milindapañha, where Nāgasena responds to King Milinda’s question about rebirth. Milinda asks whether it is the same person who is reborn. Nāgasena replies, “Not the same, not another”. He clarifies: it is not the same nāma-rūpa (name-and-form, i.e., the five skandhas) that is reborn, but due to karmic causes, a new being arises — not as a reappearance of an existing self, nor as the reincarnation of some lingering nāma-rūpa elements such as memories or mental traits, but as the effect of a causal transmission, like one billiard ball striking another. Karma is thus what connects one stage of the process to the next. It is not identity that persists, but causality.

This view offers a compelling answer to the apparent contradiction: karma does not require a self to function; rather, it is the continuity of karmic causality that makes the illusion of selfhood possible in the first place. Without this web of conditional relations, there would be no basis for speaking of a unified person at all. The question is therefore not “How can there be karma if there is no self?” but “How could the illusion of self arise without karma?”, i.e., without the causal mechanisms that give rise to and sustain the very continuity mistaken for a self.

Karma and free will

Let’s now turn to another important aspect that arises from the law of karma: the question of agency and free will. If there is no permanent self, what kind of agency or freedom remains? According to the Buddhist model of the mind as a conditioned process (also see anatta-doctrine and the Five Skandhas), there is no singular, stable will — that is, not a single, central decision-maker that exists independently of mental states, emotions, habits, and bodily processes. What we call ‘will’ is itself the outcome of these interacting conditions — not their source. Instead, what we call ‘will’ is itself a product of these processes. Still, this does not imply fatalistic determinism. Rather, the human being is understood as a dynamic configuration of interacting processes: sensations, thoughts, intentions, and habits. These event-streams are causally interconnected but not rigidly fixed. Just as a person can train themselves to speak a new language, gradually reconfiguring their brain’s circuitry and habits of thought in the process, the mind can also intervene in its own unfolding — through mindful awareness, ethical reflection, and meditative discipline.

In this sense, the Buddhist view again articulates a middle path between determinism and absolute freedom. We are undeniably conditioned — by biology, psychology, and social context — but we also possess the capacity for internal transformation. The process-self, lacking a metaphysical core, can nonetheless influence its own development by altering the very factors that condition future experiences. Even if each moment is determined by prior causes, the system as a whole — through feedback, memory, and intentional practice — can bend the trajectory of its own unfolding. What may seem like free will is not the action of an inner essence, but the emergent capacity of a causally interlinked system to reshape itself over time.

Conclusion

Siddhartha Gautama’s reinterpretation of karma and samsara marked a radical departure from the metaphysical frameworks of his time. Instead of positing a stable self (ātman) migrating through literal rebirths, he uncovered a structure of dependent conditions in which identity and suffering arise. This shift from metaphysical continuity to causal process reframed the human condition not as being trapped in a cosmic machinery, but as being entangled in one’s own habits of mind. The illusion of self — the very belief in someone who suffers, acts, and is reborn — arises not from any underlying substance but from the conditioned interplay of intentions, perceptions, and impressions.

In this view, karma does not require a self to “own” it. Rather, it is the law-like unfolding of intention and result that sustains the appearance of a self. Just as one billiard ball strikes another, volitional formations (karma) give rise to consciousness, identity, and world. What continues is not a person, but a stream of conditioned becoming. Without karma, there would be no causal link across moments — and therefore, no illusion of personal continuity. Siddhartha turned the philosophical question on its head: not “How can karma operate without a self?” but “How could the illusion of self arise without karmic continuity?”

This has profound consequences not only for metaphysics, but for ethics and spiritual practice. In place of metaphysical responsibility, there emerges a functional moral dynamic: every action shapes the structure of future experience. Yet this is not a deterministic worldview. On the contrary, the Buddhist model offers a middle path — recognizing that while we are shaped by causes, we are also capable of reshaping those causes. Through ethical discipline, meditative training, and insight, one can influence the stream of becoming. Autonomy arises not from a metaphysical free will, but from the feedback and self-modifying capacity of a causal system aware of itself.

Furthermore, Siddhartha Gautama rejected the idea that liberation is achieved through the accumulation of good karma. Even wholesome karma binds one to samsara if it remains within the realm of conditioned causality. The goal is not to max out one’s karmic merit, but to dissolve the very structure — craving, clinging, ignorance — that makes karma operative. Liberation (nirvāṇa) is the cessation of this compulsive becoming. The karmic account is not to be filled, but to be closed.

This stands in marked contrast to many strands of Western thought. Where Western religions often imagine an immortal soul judged by a transcendent deity, and Western philosophy often defends a rational ego or agent, the Buddhist view is radically non-essentialist. It locates moral responsibility, suffering, and liberation not in some metaphysical core, but in the dynamic of moment-to-moment construction. It invites practitioners not to speculate on an afterlife, but to examine the mechanisms of suffering here and now.

In this sense, Siddhartha’s reframing of karma and samsara is not merely an ancient doctrine, but a therapeutic insight: we suffer not because of what we are, but because of how we construct ourselves. And the way out lies not in escaping to another world, but in interrupting the process — moment by moment, volition by volition — until suffering ends.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- SN (Saṃyutta Nikāya) 12.2 (Paṭiccasamuppāda Sutta)

- Abhidhamma Piṭaka, particularly the Dhammasaṅgaṇī and commentaries

- AN (Aṅguttara Nikāya) 3.61

- SN (Saṃyutta Nikāya) 22.59 (Anattā-lakkhaṇa Sutta)

Footnotes

-

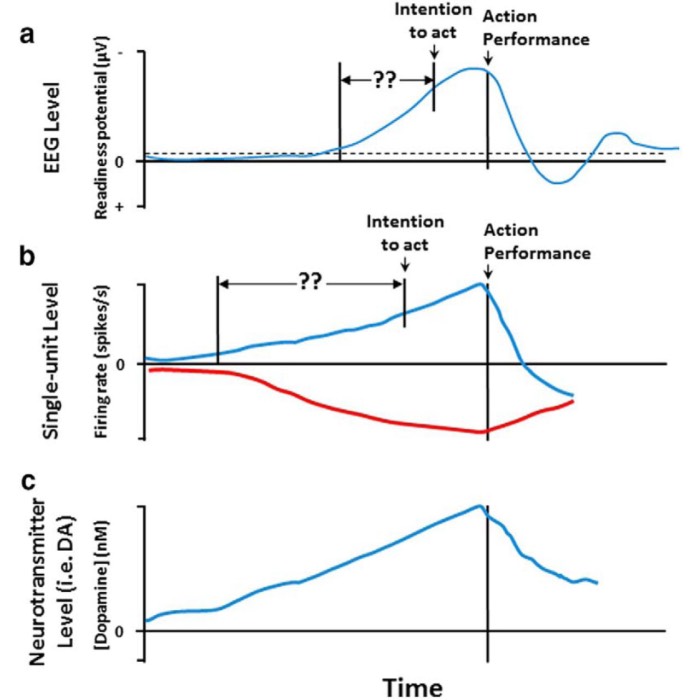

This idea of a continuous stream of consciousness without a fixed self finds interesting parallels in modern neuroscience. ↩

comments