Śūnyatā and the Two Truths: Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka philosophy

Nāgārjuna, the second-century Buddhist philosopher and founder of the Madhyamaka school, is best known for his radical teaching of śūnyatā — emptiness — and his systematic articulation of the two truths doctrine. These two pillars are deeply intertwined: śūnyatā reveals that no phenomenon possesses an intrinsic essence, and the two truths framework explains how this emptiness can be understood, communicated, and lived without collapsing into nihilism or dogma.

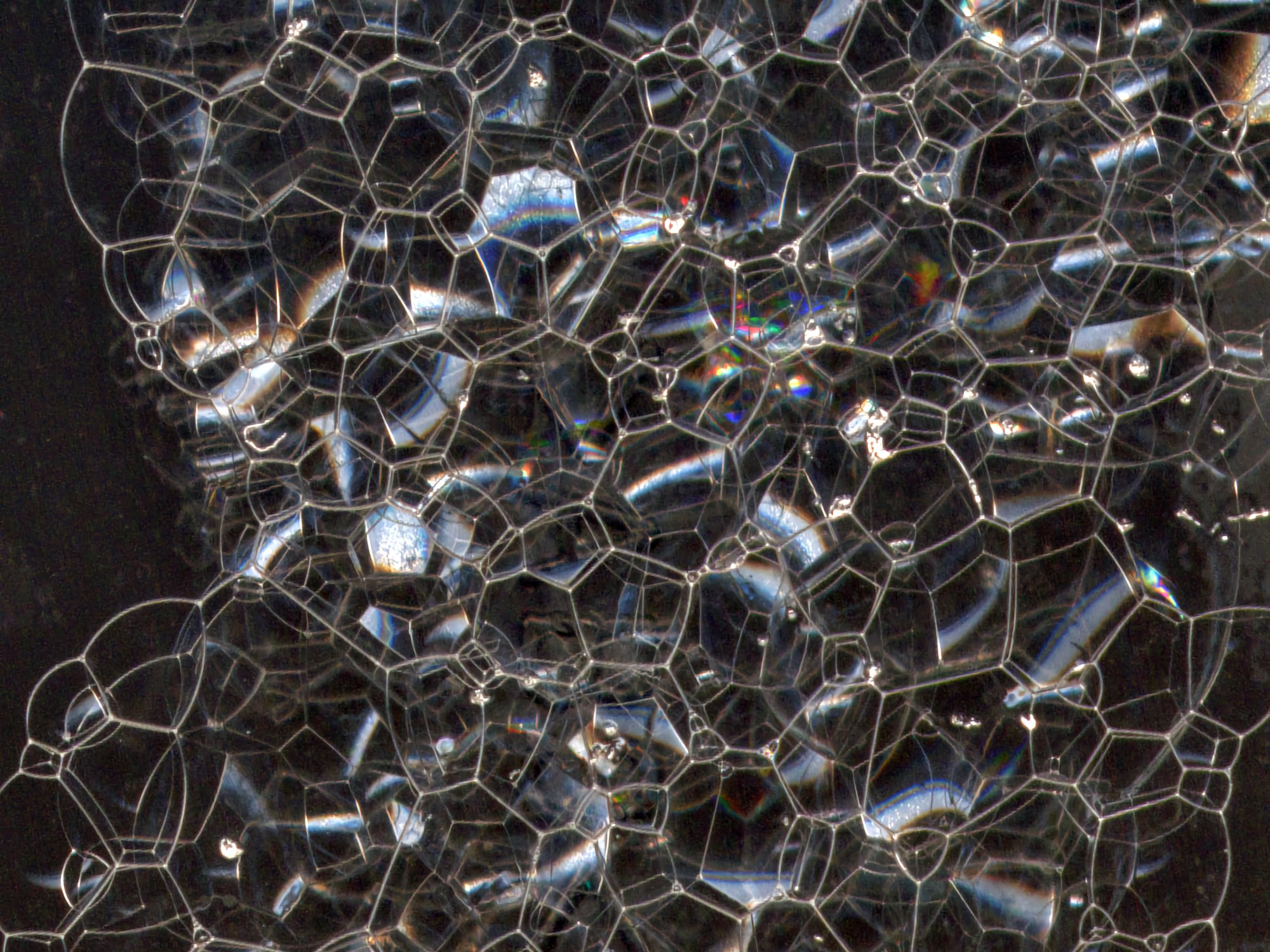

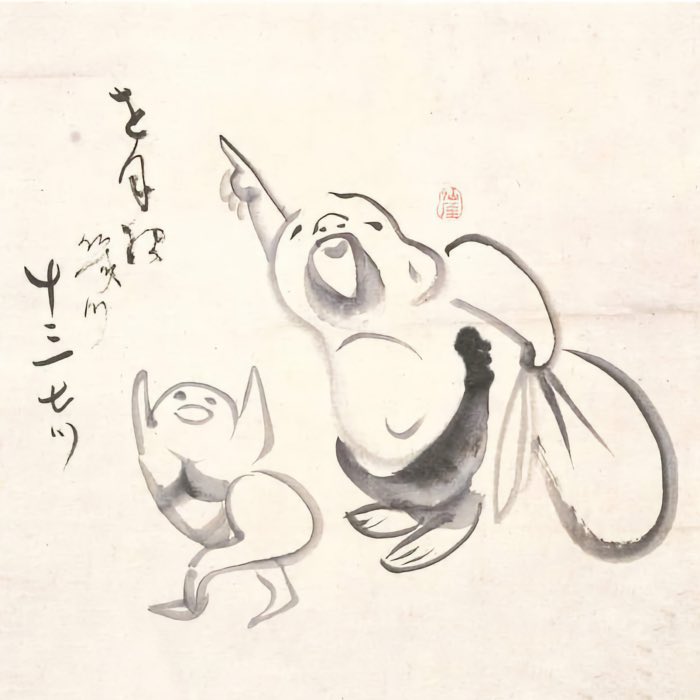

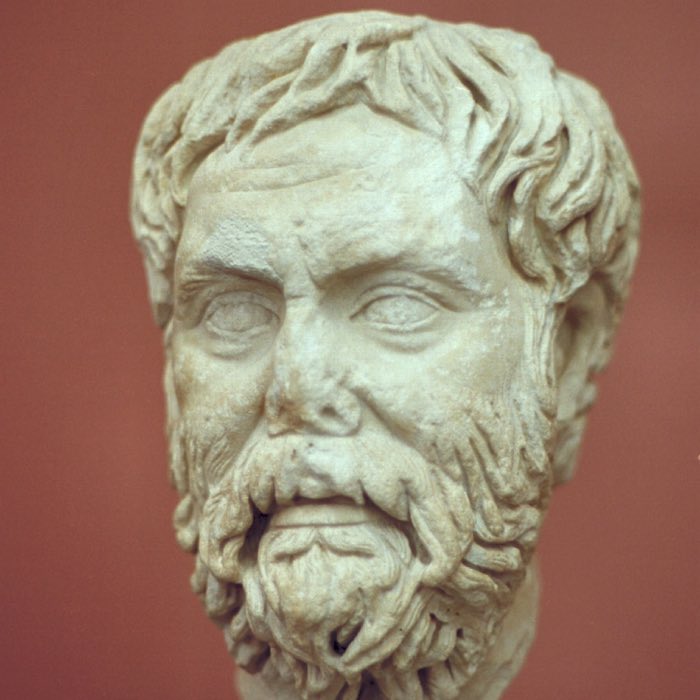

A simile from the Pāli scriptures (SN 22.95) compares form and feelings with foam and bubbles. This simile is often used to illustrate the central insight of Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka philosophy: that all phenomena lack intrinsic essence (svabhāva) and arise dependently through causes and conditions. Like the bubbles, they appear, persist briefly, and dissolve — neither entirely real nor entirely unreal. This captures the meaning of śūnyatā (emptiness) and the function of the two truths in navigating conventional appearances without reifying them. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5) (modified)

At its heart, śūnyatā means that nothing exists independently; all things arise in dependence on conditions. This includes not only external phenomena but also the self, the Dharma, and even the concepts we use to navigate the world. For Nāgārjuna, emptiness is not an esoteric idea but a tool to free the mind from reification — the habit of mistaking temporary, contingent processes for permanent entities. The two truths doctrine — distinguishing between conventional and ultimate truth — allows him to express this insight without rejecting the everyday world. On the contrary, it affirms the functional validity of ordinary experience while revealing its lack of inherent substance.

Far from being a purely theoretical stance, Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka philosophy has profound existential and practical consequences. By undermining clinging to identity and fixed views, it opens the path to liberation. And by dissolving the boundary between self and other, it gives rise to a natural, spontaneous compassion. These insights not only shaped the course of Indian Mahāyāna thought but also laid the foundation for later traditions — especially Zen Buddhism — where the direct, experiential realization of emptiness and the non-duality of form and emptiness become central to practice.

In this post, we explore the logic, significance, and enduring influence of śūnyatā and the two truths in Nāgārjuna’s thought, not only as a philosophical critique, but as a transformative vision for how we see, feel, and act in the world.

Emptiness and the absence of intrinsic essence

Nāgārjuna’s teaching of śūnyatā does not emerge in isolation from early Buddhism. The notion of emptiness appears already in the Pāli canon, where it is often used adjectivally. In Saṃyutta Nikāya 35.85, Siddhartha Gautama states:

“Empty is the world, empty is the world, O lord, they say. But in what way is the world said to be empty?” - “What, Ananda, is empty of me and of what belongs to me, to that, Ananda, is said: ‘Empty is the world’. But what is empty of me or belonging to me? The six inner and outer realms, the six kinds of consciousness, the six touches, the eighteen feelings. That is empty of I and of what belongs to the I.”

– Saṃyutta Nikāya 35.85

Here, emptiness refers not to a metaphysical void, but to the absence of anything that can be regarded as inherently ‘mine’ or ‘me’. Nāgārjuna’s later refinement of this idea is thus in direct continuity with the Buddha’s original insight — that what we experience is empty of any fixed identity or possessive essence.

This radical rejection of intrinsic essence is laid out already in the first chapter of his Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, where Nāgārjuna writes:

Not from oneself,

not from another,

not from both,

and not without cause have any things arisen anywhere and at any time.– MMK 1.1

These fourfold negations dismantle all possible theories of causation that would reintroduce essence or fixity into reality. By excluding all static origins, Nāgārjuna affirms that all phenomena arise purely through conditionality — that is, without essence.

Nāgārjuna’s understanding of śūnyatā is fundamentally rooted in his critique of svabhāva, the idea of intrinsic or self-existing essence. In classical Indian thought, particularly within Brahmanical traditions, svabhāva often refers to the inherent nature of a thing — its unchanging core that makes it what it is, regardless of context. Nāgārjuna challenges this assumption at its root. He argues that to posit such an intrinsic nature is to misunderstand the basic structure of reality as it is taught in early Buddhism.

According to Nāgārjuna, to claim that something possesses svabhāva implies that it exists independently, from its own side, and without being affected by or dependent upon anything else. To illustrate: if we were to claim that a flame has an independent essence — that it exists in and of itself — we would overlook the fact that it depends on oxygen, fuel, ignition, and environmental conditions. Without these, the flame ceases to exist. The flame is not an independently existing thing but a phenomenon arising from specific conditions, just as all phenomena are.

The svabhāva concept stands in direct opposition to the foundational Buddhist principle of pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination), which holds that all phenomena arise due to specific causes and conditions and exist only as part of a continuous interplay of conditions and effects. This is what is meant by a process-like structure of reality: all things arise, change, and cease in dynamic dependence upon countless interacting factors. There is no stable core that endures through time.

But no such thing can be found. Everything follows the pattern of conditionality and is thus impermanent, contingent, and dependent. From the Buddhist perspective, to assume the presence of intrinsic essence is to misread the nature of reality.

Thus, Nāgārjuna introduces the term śūnyatā to capture the insight that no phenomenon possesses an intrinsic nature. Śūnyatā is not an abstract or mystical principle, but a critical negation of svabhāva. It points to the absence of independent essence in all things, including the self, external objects, and even conceptual constructs like the Dharma itself — which is, according to Nāgārjuna, not a fixed or eternal doctrine, but a set of teachings that function within specific contexts and lose meaning when treated as absolute.

A simple example can illustrate this. Take an apple: it appears as a discrete object, yet what we call an apple consists entirely of things that are not an apple — sunlight, water, genetic material, agricultural processes, cultural language. Its apparent identity is a temporary configuration of conditions. As Nāgārjuna puts it in the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (MMK 7.17): “Something that is dependent for its existence on another thing is not to be regarded as a real thing.”

This becomes particularly clear when we reflect on the Dharma itself. For example, the teaching of the Four Noble Truths cannot be understood apart from the specific context of suffering and liberation they are meant to address. These truths are not self-evident axioms existing independently of human experience; they gain their meaning only in relation to the existential problems they respond to, the conditions of life they are embedded in, and the interpretive frameworks we apply to them. Like a map that is useful only within a particular terrain, the Dharma has no absolute status outside its function within a web of conditions. This illustrates that even the core teachings of Buddhism are not exceptions to śūnyatā, but examples of it.

Everything is what it is only in dependence upon what it is not.

As Nāgārjuna also affirms in MMK 13.3:

All things are without essence because one can see a change of essence in them. Because of the emptiness of all things, however, there is no thing without being.

This insight highlights that emptiness does not negate existence, but rather reveals it as fluid and relational — never fixed or self-contained.

Dependent origination and emptiness

This relational understanding of phenomena is captured succinctly in Nāgārjuna’s Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (MMK), most famously in verse 24.18:

We state that conditioned origination is emptiness. It is a dependent designation, and is itself the middle way.

This short verse encapsulates one of the most important insights in all of Buddhist philosophy. It equates three key ideas: pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination), śūnyatā (emptiness), and the madhyamā pratipad (Middle Way). To say that something is empty is to say that it arises dependently; and to say that something arises dependently is to say that it lacks intrinsic essence. This formulation is Nāgārjuna’s great philosophical synthesis — not a new invention, but a radical clarification of the Buddha’s core insight.

In early Buddhism, pratītyasamutpāda explained how suffering arises and ceases through conditioned processes (as seen, for example, in the twelve links of dependent origination). Nāgārjuna expands this view, applying it not only to psychological and existential processes, but to all conceptual and ontological claims. Everything — the self, external objects, the Dharma, even nirvāṇa — exists only in dependence on causes, conditions, and mental designations. Nothing stands alone. And this absence of self-existence is precisely what śūnyatā means.

By making this equation explicit, Nāgārjuna safeguards the Dharma against the risk of being reinterpreted in static or substantialist terms. Buddhist concepts, while powerful, are often at risk of being misunderstood as metaphysical absolutes. One might begin to treat nirvāṇa as a transcendent substance, or take the Four Noble Truths as timeless facts existing independently of context. But śūnyatā reminds us that even the most foundational teachings are empty of fixed essence: they function only within the web of interdependence.

This has deep implications for practice. By recognizing the emptiness of all phenomena, the practitioner ceases to cling — not just to the self or the world, but even to the teachings themselves. Śūnyatā is thus a powerful form of upāya (skillful means): it shows that liberation does not come from building a more accurate metaphysical picture, but from letting go of the illusion of intrinsic existence. Even emptiness, Nāgārjuna warns, must not be grasped. Emptiness, too, is empty.

Importantly, Nāgārjuna does not interpret dependent origination as cosmic unity or mystical connectedness. His focus is rigorously analytic: to be dependently originated means to lack svabhāva — to have no fixed, independent being. This anti-essentialist reading stands at the heart of his method and doctrine. Yet this analytic clarity does not lead to detachment from the world — rather, it allows us to see reality as a web of conditioned, impermanent, and interdependent processes. In this light, śūnyatā becomes a powerful form of upāya: a conceptual tool that dismantles illusions not by replacing them with new beliefs, but by loosening the grip of all fixed views. Even emptiness itself must ultimately be released. The goal is not to believe in emptiness, but to see through the illusion of fixed existence — whether in the self, in objects, or in the Dharma. In this sense, Nāgārjuna’s teaching fulfills and deepens Siddhartha Gautama’s insight that liberation comes not only from renouncing attachments to the world, but from relinquishing even the conceptual frameworks that sustain them.

The two truths framework

In order to prevent misunderstandings, Nāgārjuna articulates the doctrine of the two truths (satya-dvaya): conventional truth (saṃvṛti-satya) and ultimate truth (paramārtha-satya). These are not two separate realities but two perspectives on the same reality.

Conventional truth refers to our everyday language, categories, and experiences — the shared world of names, functions, and social roles. It allows us to live, communicate, and practice. Ultimate truth, by contrast, refers to the insight that all these phenomena are ultimately empty of intrinsic nature.

Nāgārjuna introduces the two truths not as a later philosophical innovation, but as the very basis of the Buddha’s own method of teaching. In MMK 24.8–24.9, he writes:

In proclaiming the Dharma, the Buddhas have relied on two truths: One is the worldly, ‘veiled truth’ (saṃvṛtisatya), the other is the ‘truth in the highest sense’ (paramārthasatya). Those who do not recognize the difference between the two truths do not recognize the profound truth (tattva) in the Buddha’s teaching.

This makes clear that the distinction between conventional and ultimate truth is not peripheral but essential: it is the framework through which the Dharma becomes intelligible. Without it, even sincere engagement with the teachings can result in distortion.

Nāgārjuna emphasizes that these two truths are interdependent. As he famously writes in MMK 24.10:

Without depending on conventional truth, the ultimate cannot be taught. Without understanding the ultimate, liberation cannot be attained.

We begin with conventional truth because it’s the only ground from which communication and teaching can proceed. But by recognizing the emptiness of all things — including conventions themselves — we open the way to freedom.

Preventing the extremes of nihilism and essentialism

The two truths doctrine plays a crucial role in avoiding philosophical extremes. If we take conventional truth as ultimate, we fall into essentialism (śassatavāda, the view of eternalism, “everything in the world is transient, but there is something beyond time and space: infinite eternity”) — treating names, identities, or doctrines as independently real. But if we misinterpret śūnyatā as a denial of reality altogether, we risk nihilism (ucchedavāda, the view of total annihilation, “negating everything that exists”).

Nāgārjuna’s Middle Way avoids both. This balanced view is what Nāgārjuna refers to as the Madhyamaka (Sanskrit, “middle”) — the Middle Way — not only between indulgence and austerity, as in early Buddhist ethics, but between the philosophical extremes of essentialism and nihilism. Emptiness is not a hidden metaphysical substance; it is a way of seeing that dismantles reified views. When we understand that even emptiness is empty, we see that all truths are functional — not final. This understanding enables continued ethical action, communication, and meditation without delusion.

For Nāgārjuna, the world is not a domain of being, but of ceaseless becoming. Things do not statically exist; they occur — like a melody, which exists only in the unfolding sequence of tones. This also applies to the aggregates (skandhas), which do not exist independently but are embedded in the web of dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda). Since dependence and emptiness are identical, things do not truly arise or perish. As he writes in MMK 21.11:

For you it may be that arising and ceasing are indeed seen. But they are seen only through delusion.

Nāgārjuna’s statement does not deny change or experiential transformation. Rather, it refutes the notion that things with fixed identity come into existence or pass out of it. To say something truly arises or ceases is to assume it exists either from its own side or from a definable origin — both of which are denied by dependent origination. In truth, what we take to be arising is the coming together of conditions, and what we take to be ceasing is their dispersal. There is no self-contained entity that travels through these phases. This perspective aligns with Siddhartha Gautama’s original insight that all phenomena are processual — not static things, but unfolding activities without a stable core. What we call ‘things’ are momentary appearances within an ever-changing interplay of conditions.

Both eternalism and annihilationism project a kind of substance into things — something indestructible in the first case, something that emerges and vanishes absolutely in the second. But since becoming lacks any stable core, nothing truly persists (śāśvata), and nothing absolutely disappears (uccheda). Nāgārjuna likens this misunderstanding to illusions and mirages — phenomena that seem real when grasped uncritically, but dissolve under analysis. As he writes in MMK 7.34:

Arising, abiding, and ceasing are regarded like magic, like a dream, like a mirage.

What depends on conditions is empty. What is empty does not possess any independent reality. Like waves on the ocean’s surface, phenomena appear and vanish without gaining or losing substance. They do not emerge from nothing, nor endure forever, but continuously arise within a nexus of conditions so interwoven that no first cause or ultimate ground can be identified.

From this realization, Nāgārjuna proceeds to one of his most famous conclusions — that the highest insight (prajñā) reveals no ultimate difference between saṃsāra and nirvāṇa:

There is not the slightest difference between nirvāṇa and saṃsāra. The limit of saṃsāra is the limit of nirvāṇa. Not even the finest distinction can be found between the two.

– MMK 25.19–20

From the standpoint of awakening, the duality between conditioned existence and unconditioned liberation collapses. These are conceptual opposites that only persist in delusion. To cling to one or reject the other is to impose an artificial boundary. Because emptiness is liberation, all beings are already situated within the horizon of release — what is needed is not to attain it as a personal goal, but to recognize it without appropriation. As Nāgārjuna warns in MMK 16.9:

‘I will become extinguished without grasping — for me there will be nirvāṇa!’ Those who are caught in such delusion are themselves most firmly grasping.

True insight is not the possession of nirvāṇa, but freedom from the very notion of possession.

The significance of the Middle Way in Nāgārjuna and the Buddhist tradition

The philosophy of the Madhyamaka has had a profound influence on various Mahāyāna schools. While not all schools follow Madhyamaka perspectives identically, Tibetan Buddhism and Zen in particular are deeply rooted in its view. The Zen tradition, especially, expresses Nāgārjuna’s insight in poetic and experiential language — most famously in the Heart Sūtra, which states:

Form is emptiness, and emptiness is form.

This phrase captures the core Madhyamaka understanding that conventional appearance and ultimate emptiness are not opposed, but interdependent expressions of the same reality. The Tendai, Sanron, and Maha Madhyamaka traditions also continue this legacy.

The Middle Way is synonymous with the Noble Eightfold Path. It is understood as a guiding principle for avoiding extremes — whether in belief or practice. During Siddhartha Gautama’s time, many religious movements were marked by extreme asceticism or sensual indulgence. Gautama himself was initially part of an ascetic school that pushed the body to the edge of collapse in the search for transcendence. He later testified that only by abandoning such extremes did true insight arise — not through effort, but by letting go.

The Middle Way is thus a principle of moderation: insight does not lie in denying life’s needs nor in being bound to its pleasures. This is captured in the famous simile of the lute string:

If the string is too loose, it makes no sound. If it is too tight, it snaps. Only when it is tuned between these extremes can it produce a harmonious tone.

Beyond external behavior, the Middle Way also applies to mental tendencies — particularly the extremes of greed (lobha), rāga) and aversion (dosa). Ajahn Chah described it this way:

From dualistic thinking, we always see two sides: this side here and that side there. People tend to walk on one side or the other. When there is love, we follow the path of love. When there is hate, we follow the path of hate. If we try to let go of both love and hate, that is the path of the middle.

– paraphrased from Ajahn Chah (sourceꜛ)

Nāgārjuna transforms this ethical Middle Way into a philosophical one. He argues that four extreme views should be avoided:

- that things exist from themselves (substantialism),

- that they exist only in the mind (subjectivism),

- that both are true simultaneously (dualism/dual assertion),

- or that neither is true (nihilism/negational absolutism).

Instead, all things exist dependently. The Noble Eightfold Path describes how one should act, speak, and think in a way that avoids these views. Existence is not denied (no nihilism), but the existence of eternal, independent substances is. Phenomena arise from conditions; when those conditions change, the phenomena change or dissolve. And so do the things dependent on them. There is nothing with a permanent core — only interdependent arising and existence. No eternalism, no annihilationism — both are avoided at once. This, too, is the Middle Way.

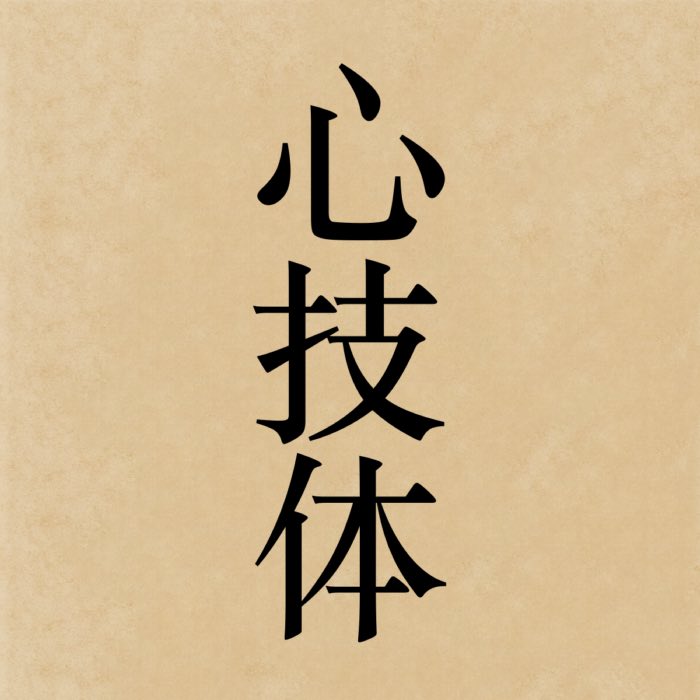

Implications for thought and practice

The fusion of śūnyatā and the two truths reshapes both thought and practice. It demands a radical reorientation: to use concepts without becoming bound by them, to act in the world without clinging to any fixed identity or ideology. Intellectual flexibility becomes not a passive openness, but a disciplined refusal to reify — even the view of emptiness must be let go when it has served its purpose. In practice, this fusion encourages a life of wise engagement: grounded in compassion, yet free from grasping; attuned to suffering, yet not caught in it. We speak, think, and act — but with the recognition that all forms, including our own self-conception, are provisional, relational, and contingent upon conditions. This insight undermines the grasping that gives rise to suffering: when we realize that the self and others are not fixed entities but dependently arisen processes, compassion naturally arises. Others are no longer seen as static or separate, but as co-arising patterns caught in the same flux as ourselves. This shift loosens the illusion of separateness — the very root of clinging and aversion — and opens a space for wise action grounded not in reactivity, but in clarity and care. Liberation, then, is not a matter of escaping the world, but of ceasing to be entangled in misperceptions about it: it emerges through seeing rightly, which is simultaneously a release from suffering and a deepened responsiveness to the world.

This understanding is central to Buddhist meditation. Thoughts, emotions, identities — even the idea of a meditator — are not enemies to be eradicated, but phenomena to be seen clearly as momentary configurations of causes and conditions. Meditation becomes not an escape, but an intimate encounter with the constructed nature of experience. Liberation arises not from transcendence of the world, but from ceasing to be deceived by it — from seeing through the illusions of solidity, independence, and permanence that bind us to suffering.

Conclusion

Nāgārjuna’s teaching of śūnyatā and the two truths offers a transformative vision of reality — not as a collection of self-existing entities, but as a dynamic web of interdependent processes. By dismantling the notion of svabhāva (intrinsic essence), he affirms that all things, including the Dharma itself, are empty of fixed nature. Yet this emptiness is not a denial of existence; it is an invitation to see the world more clearly — without the filters of reification, essentialism, or nihilism. The doctrine of the two truths ensures that this insight does not spiral into despair or silence, but remains grounded in the functional world of practice, ethics, and compassion.

Crucially, Nāgārjuna does not offer a metaphysical system to replace others; he dismantles the very need for one. In this, his approach both resonates with and exceeds certain strains of Western philosophy. While thinkers such as Kant, Wittgenstein, and Derrida have exposed the instability of conceptual knowledge, Nāgārjuna goes further by revealing the conditioned nature of all aspects of experience — not just our thoughts, but the thinker, the object, and the context. Where Western metaphysics often seeks a stable foundation in reason, language, or being, Nāgārjuna points instead to a radical groundlessness — and yet from this very groundlessness, a deeper clarity and compassion can emerge.

This radical middle path avoids both extremes of absolutism and relativism. By affirming conventional truth while exposing its provisional nature, Nāgārjuna charts a course of engagement without fixation. It is precisely because no view is final that dialogue, action, and care become possible. Rather than clinging to doctrines, including the doctrine of emptiness itself, we are invited to act wisely in a world understood as contingent and co-arising. This frees the practitioner not only from metaphysical delusions but also from the reactive patterns of craving and aversion.

In this way, Nāgārjuna’s framework is not simply a critique of philosophical error — it is a path to liberation. By seeing through the illusions of essence and embracing the dynamic, dependent nature of all things, one cultivates a mind that no longer grasps. Compassion arises naturally when we recognize that others, like ourselves, are not static beings but processes shaped by conditions. And liberation, in turn, is not some distant metaphysical attainment, but the lived freedom that flows from no longer being deceived by appearances.

This vision has proven foundational not only for later developments in Buddhist philosophy, but also for lived practice traditions such as Zen. The Madhyamaka insight into śūnyatā and the two truths gave Zen its philosophical backbone: the ability to hold silence and speech, form and emptiness, everyday mind and awakened mind, as not-two. Zen’s emphasis on direct experience, its refusal to cling to doctrines or texts, and its spontaneous, paradoxical expressions all trace back to Nāgārjuna’s dismantling of conceptual reification. In Zen, to see the ‘suchness’ of reality is to live the Middle Way — to walk, sit, and speak from the recognition that form is emptiness, and emptiness is none other than form.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Bernhard Weber-Brosamer, Dieter M Back, Die Philosophie der Leere: Nagarjunas Mula-Madhyamaka-Karikas, 2006, Harrassowitz, O, ISBN-10: 9783447052504

- Lutz Geldsetzer, Nagarjuna, Die Lehre von der Mitte - (Mula-madhyamaka-karika) Zhong Lu, 2010, Meiner, F, ISBN: 9783787321377

- Nāgārjuna, David J. Kalupahana, Mūlamadhyamakakārikā of Nāgārjuna, 1991, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN: 9788120807747

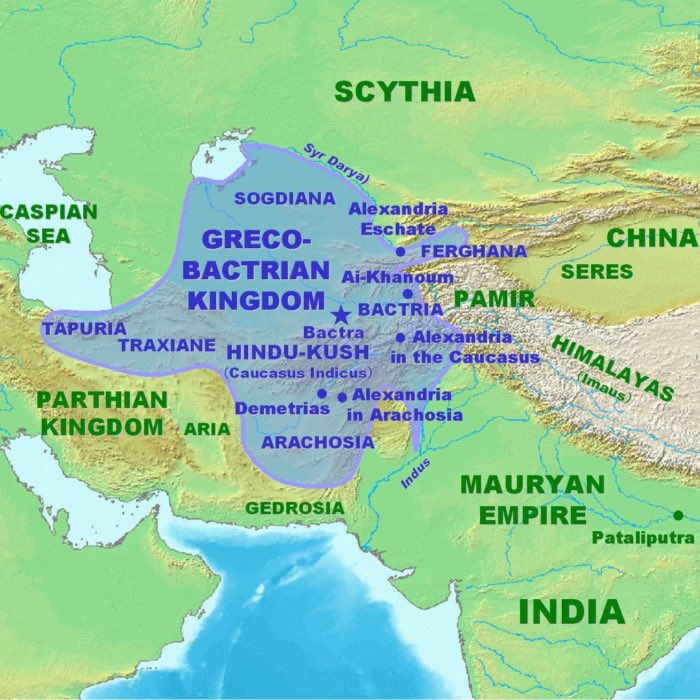

- Christopher I. Beckwith, Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia, 2015, Princeton University Press, ISBN 10: 0691166447

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

comments