Shushō ittō: Practice-enlightenment in Dōgen’s Zen

Among the many profound contributions that Dōgen Zenji made to Buddhist philosophy, the concept of “practice-enlightenment” (shushō ittō, 修輯一等) stands as one of the most revolutionary and defining. This principle radically reframes the traditional Buddhist relationship between practice (shushō) and enlightenment (satori or bodhi), asserting that the two are not separate stages but an indivisible unity. Understanding practice-enlightenment is essential to grasping Dōgen’s vision of the Buddhist path and the impact he has left on Zen thought.

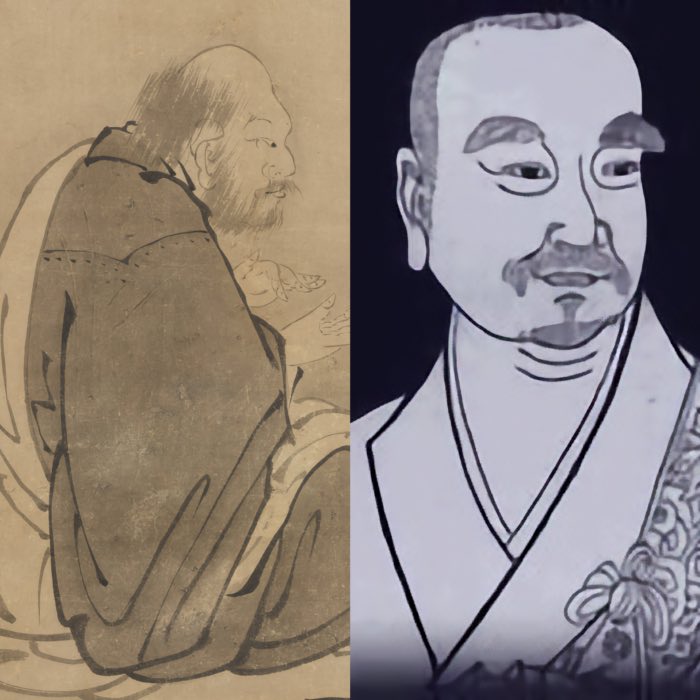

The meditation hall at Soji-ji near Tokyo, Japan. Dōgen Zenji (道元禅師, 1200-1253) was the founder of the Sōtō school of Zen Buddhism in Japan and is known for his teachings on zazen (座禅, seated meditation) and the nature of practice-enlightenment. His writings emphasize the inseparability of practice and realization, with a focus on the immediacy of awakening in every moment. This perspective challenges traditional views that separate practice from enlightenment, instead emphasizing the unity of both. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Traditional views of practice and enlightenment

In much of traditional Buddhist discourse, practice is seen as the means to attain the goal of enlightenment. The practitioner, unenlightened at the outset, engages in meditation, ethical conduct, and wisdom cultivation to progressively purify the mind and eventually realize awakening. This sequential model, emphasizing gradual progress toward a future goal, shaped much of Indian, Chinese, and early Japanese Buddhist thought.

Even within Chán (Zen) Buddhism, debates existed between “sudden enlightenment” and “gradual cultivation” (see our previous article on the Northern and Southern School). Although sudden enlightenment proponents argued that awakening could happen in an instant, the tension between practice as a preparatory effort and enlightenment as an ultimate realization remained.

Dōgen’s radical reinterpretation

Dōgen rejected the dualistic notion that practice and enlightenment are distinct either in time or in their essential nature. In his view, true practice is not a preparatory stage leading toward a future enlightenment; it is already the full and immediate expression of enlightenment itself. To engage sincerely in zazen (seated meditation, 座硅) is to embody Buddha-nature directly. Likewise, to act ethically, to cook, to clean, to walk — all these activities, when performed with full awareness, presence, and non-attachment, are enlightenment manifesting vividly in the world.

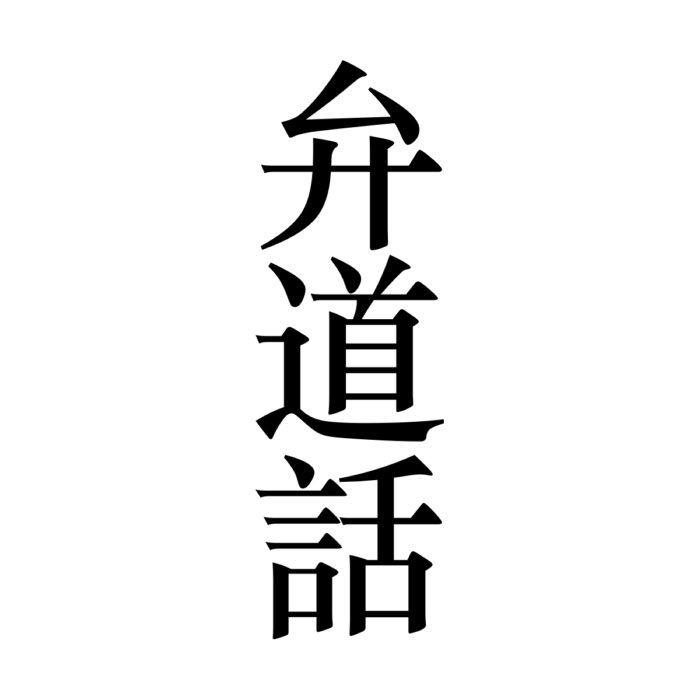

In Bendōwa (Negotiating the Way, 談道和), Dōgen famously writes:

Practice and realization are one and the same. Because practice is based directly on enlightenment, the practice of a beginner is itself the entirety of original enlightenment.

This radical assertion overturns the common view that practice is merely an arduous journey toward some distant satori (視道) or bodhi (滅道). Instead, Dōgen reveals that each moment of genuine practice is the complete manifestation of Buddha-nature (佛性) itself. There is no gap between practicing and awakening; there is only the wholehearted actualization of the Way in every step, every breath, and every task.

Implications of practice-enlightenment

This view has several profound implications:

- Non-teleological practice: Practice is not driven by a desire for future attainment. Sitting in zazen is not a technique to acquire enlightenment later; the very act of sitting is the full embodiment of awakening. Each breath, each moment of sincere sitting, manifests Buddha-nature completely and requires no external validation or result.

- Equality among practitioners: In Dōgen’s vision, beginners and experienced practitioners stand on the same ground of realization when they practice with sincerity. There is no fundamental difference between the one who has practiced for decades and the one who has just begun. Both participate directly in the activity of enlightenment, dissolving hierarchical notions of “unenlightened” and “enlightened”.

- Everyday life as practice: Enlightenment is not limited to the meditation hall or the formalities of religious rituals. Activities such as cooking, eating, sweeping, and even casual conversation, when performed with complete presence, sincerity, and without dualistic striving, are fully the activities of awakening. In Dōgen’s teaching, the entirety of daily life becomes sacred and integral to the path.

- Continuous realization: Enlightenment is not a static achievement or a final destination reached once and for all. It is an ever-unfolding, dynamic process that reveals itself in each new moment through continuous, wholehearted practice. Every moment of awareness deepens the realization of the Dharma, and thus enlightenment is lived anew, endlessly actualized rather than finally attained.

Practice-enlightenment in Shōbōgenzō

Dōgen elaborates on practice-enlightenment throughout his major work, the Shōbōgenzō, a monumental collection of essays articulating the deepest dimensions of Buddhist practice and realization. In fascicles such as Genjō Kōan (Manifestation of Reality, 現成公案) and Uji (Being-Time, 有時), he emphasizes that reality unfolds completely and without remainder in each and every moment, and that our ordinary lives are themselves the full site of Buddha-activity when lived with complete awareness and sincerity.

In Genjō Kōan, Dōgen expresses this pivotal insight:

“To carry yourself forward and experience myriad things is delusion. That myriad things come forth and experience themselves is awakening.”

Here, Dōgen illustrates a radical shift: moving from a self-centered striving to an effortless allowing of reality’s unfolding. In delusion, the self tries to grasp or manipulate the world; in awakening, the world reveals itself, with the self no longer standing apart or attempting to dominate. This insight strikes at the heart of practice-enlightenment: true practice arises not from achieving some fixed state, but from fully participating in the dynamic flow of reality without the burden of self-centered effort.

By living with complete sincerity and awareness, every act becomes Buddha-activity. Whether walking, working, or sitting in meditation, the practitioner is not moving toward enlightenment; they are already immersed within it, enacting it with body, speech, and mind in every moment.

Uji further deepens this understanding by presenting time itself as not a linear progression but the dynamic unfolding of existence. For Dōgen, each moment of being is not merely passing away but is the full manifestation of existence-time. In realizing practice-enlightenment, the practitioner actualizes the total reality of each moment, understanding that “being” and “time” are inseparably one. Thus, practice-enlightenment is not just about human effort but about attuning oneself to the fundamental nature of existence itself, where every moment is both the full presence of being and the dynamic flow of impermanence.

Conclusion

Dōgen’s concept of practice-enlightenment presents a decisive break from traditional, goal-oriented interpretations of Buddhist practice. By asserting the fundamental unity of practice and awakening, Dōgen removes the notion of a linear path leading toward a future realization. Practice itself, performed wholeheartedly and without striving, is the immediate expression of enlightenment. This redefinition brings a radical immediacy and practicality to Zen, emphasizing that awakening is embedded within ordinary, everyday activities.

Compared to earlier schools of Buddhism, including Indian Mahāyāna traditions and even contemporaneous Chán lineages, Dōgen’s view stands apart by rejecting any remaining duality between the “path” and the “goal”. Where Pure Land Buddhism might stress devotion toward a future rebirth, and even sudden-enlightenment schools might retain subtle distinctions between practice and insight, Dōgen collapses all temporal and existential separation.

Zen Buddhism, in Dōgen’s articulation, offers a coherent way to address the limitations inherent in both goal-driven religious practice and abstract philosophical inquiry. By dissolving the future-oriented striving and embedding awakening within sincere, embodied activity, Dōgen provides a path that is both rigorously disciplined and immediately accessible.

In sum, practice-enlightenment redefines the spiritual journey not as a movement toward something absent, but as the continuous actualization of awakening through the fullness of each present moment.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Dogen Zenji, Shobogenzo – Die Schatzkammer des wahren Dharma-Auges, 4 Bände, 2013, Verlage: Kristkeitz Werner, Übersetzung: Ritsunen Gabriele Linnebach, Gudo Wafu Nishijima, ISBN: 9783921508909

- Dogen Zenji, Unterweisungen zum wahren Buddha-Weg. Shobogenzo Zuimonki (2011), Verlage: Kristkeitz Werner, ISBN: 9783932337680

- Dogen Zenji, Hōkyōki, 2020, Angkor Verlag, Übersetzung: Guido Keller, Taro Yamada, Hidesama Iwamoto, ISBN: 9783943839821

- Dogen Zenji (Autor), Guido Keller (Übersetzer), Taro Yamada (Übersetzer), Eihei Shingi - Regeln für die Zen-Gemeinschaft, 2022, BoD – Books on Demand, ISBN: 9783988040008

- Dogen Zenji (Autor), Guido Keller (Übersetzer), Eihei Kôroku, 2017, Angkor Verlag, ISBN: 9783936018936

- Shohaku Okumura, Die Verwirklichung der Wirklichkeit - «Genjokoan» - der Schlüssel zu Dogen-Zenjis Shobogenzo, 2014, Kristkeitz, ISBN: 9783932337604

comments