Adibuddhas and the Five Tathāgatas

The concept of the Adibuddha, or “primordial Buddha”, represents one of the most profound developments in Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism. Unlike historical Buddhas such as Siddhartha Gautama, the Adibuddha is timeless and unconditioned, symbolizing the ultimate source of all awakened activity. Closely linked to the Five Tathāgatas, archetypal Buddhas embodying distinct aspects of enlightened awareness, this framework offers a rich cosmological and psychological model for understanding the nature of reality and the path to awakening. In this post, we explore the origins, symbolism, and transformative practices associated with the Adibuddha and the Five Tathāgatas, highlighting their enduring relevance in Buddhist thought and practice.

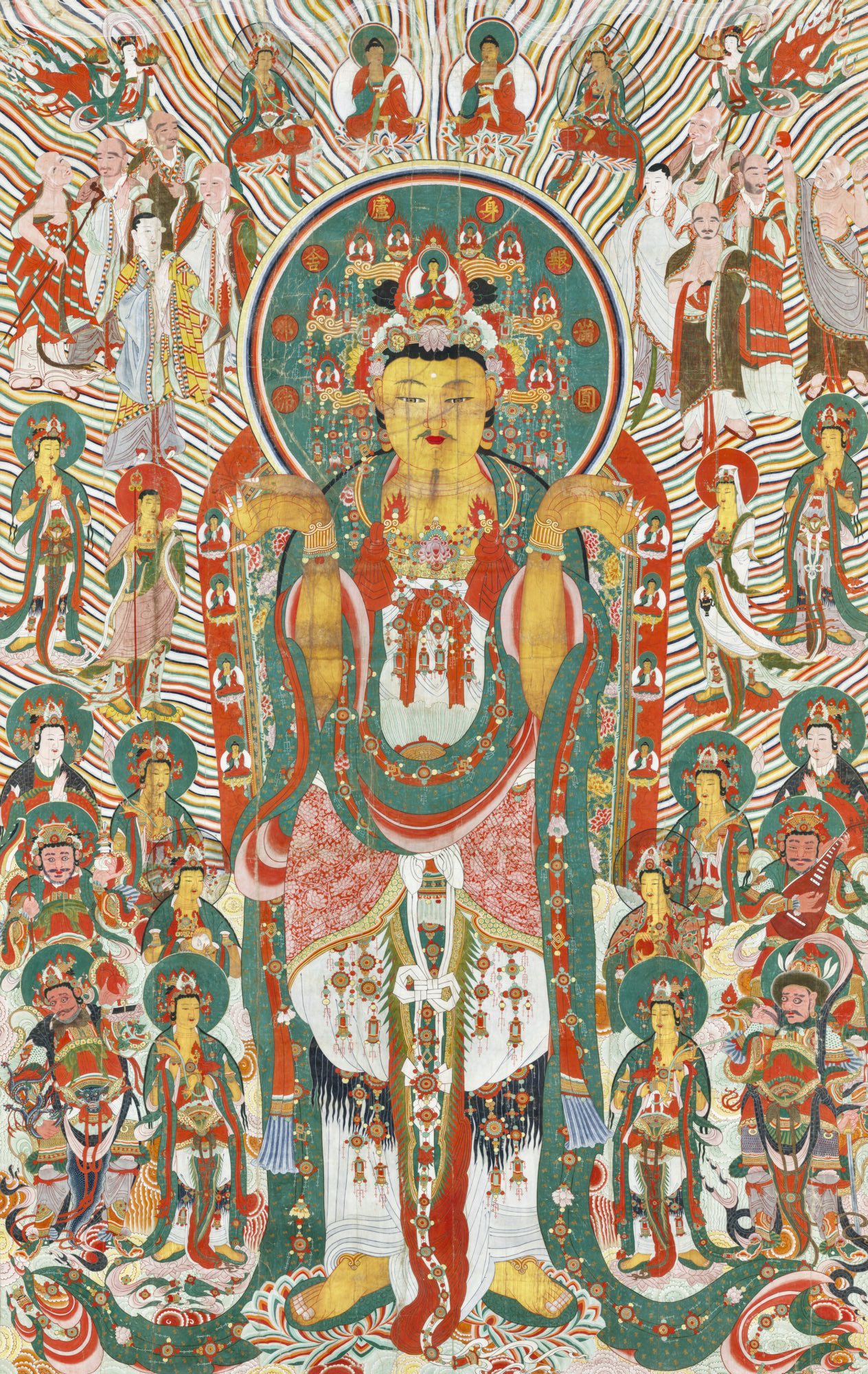

Hanging Painting of Vairocana at Sinwonsa temple in Gongju, Korea, 1664. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Introduction

The concept of the Adibuddha, the “primordial Buddha”, emerges from within Mahāyāna and becomes particularly prominent in Vajrayāna Buddhism. Unlike the historical Buddha Siddhartha Gautama, who appeared in a specific time and place, the Adibuddha is a timeless, unconditioned source of all awakened activity. This figure represents the ultimate ground of Buddhahood itself: not a person who attained enlightenment, but the innate, ever-present nature of awakened mind from which all Buddhas manifest. While the idea is not central to early Buddhist texts, it gains systematic expression in later esoteric scriptures such as the Guhyasamāja Tantra and Kālacakra Tantra.

A key distinction within Buddhist cosmology is therefore drawn between historical Buddhas, such as Siddhartha Gautama, who taught in the human realm, and transcendent Buddhas, who function as archetypal or cosmic embodiments of enlightenment. These transcendent Buddhas are not subject to the limitations of time, space, or causal origination. Among them, the Five Tathāgatas (or Five Wisdom Buddhas) are the most elaborately developed framework. They are not separate divine beings but are symbolic expressions of the five aspects of enlightened awareness. Together, they articulate a comprehensive model of reality as both psychologically transformative and cosmologically ordered.

Philosophically, the system of the Five Tathāgatas serves multiple functions. It provides a tantric map of mind and experience, where afflictive mental states are not repressed but transformed into wisdom. It also supports a vision of non-duality in which the apparent opposites, such as form and emptiness, self and other, delusion and awakening, are understood as expressions of a unified, luminous ground. In this context, the Five Tathāgatas are not merely objects of devotion or contemplation, but pedagogical tools for soteriological transformation. They form the basis for intricate ritual practices, mandalas, and meditative visualizations designed to awaken the practitioner to their own Buddha-nature.

Origins and doctrinal development of the Adibuddha concept

The idea of the Adibuddha does not appear in the earliest strata of Buddhist teachings. It begins to take shape in early Mahāyāna texts that articulate the notion of Buddha-nature (tathāgatagarbha) and the dharmakāya, the formless, universal aspect of Buddhahood. While these concepts did not yet specify a personal primordial Buddha, they laid the groundwork for later developments by emphasizing the timeless and inherent presence of awakened awareness in all beings.

The doctrinal concept of the Adibuddha becomes more explicit and fully formed in later Vajrayāna sources, particularly in tantric systems such as the Guhyasamāja Tantra, the Kālacakra Tantra, and related commentarial traditions. In these texts, the Adibuddha is not just an abstract principle but a specific figure, often named Vajradhara or Samantabhadra, who embodies the unity of wisdom (prajñā) and method (upāya), and who is seen as the ultimate source of all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. These Adibuddhas are portrayed as timeless, beyond conceptual elaboration, and inseparable from the ground of reality itself.

The emergence of the Adibuddha concept reflects a shift toward a non-dual view of awakening, where the apparent distinction between saṃsāra and nirvana, subject and object, is transcended. In this framework, the Adibuddha is not a being among others, but the luminous ground of being itself — pure awareness that underlies all phenomena. This philosophical reorientation aligns with advanced Vajrayāna practices, especially in Dzogchen and Mahāmudrā traditions, which emphasize the recognition of the mind’s primordial purity as the key to liberation.

Thus, the development of the Adibuddha concept can be seen as both a cosmological refinement and a soteriological innovation. It serves to anchor the diverse manifestations of Buddhahood in a singular, unconditioned source, while offering practitioners a vision of their own innate potential as already partaking in the nature of awakening.

The Five Tathāgatas: Symbolic and cosmological framework

The Five Tathāgatas, also known as the Five Wisdom Buddhas, represent five distinct aspects or expressions of the primordial Buddha, or Adibuddha. These Buddhas do not exist as individual, historical figures but as archetypal manifestations of enlightened consciousness. Each embodies a particular facet of awakened mind and plays a specific role in the transformation of deluded perceptions into liberating wisdom.

In the cosmological schema of Vajrayāna Buddhism, the Five Tathāgatas are arranged in a mandala, a sacred geometric configuration that maps both the external universe and the internal landscape of the mind. At the center of the mandala is Vairocana, surrounded by Akshobhya in the east, Ratnasambhava in the south, Amitābha in the west, and Amoghasiddhi in the north. This spatial arrangement is not merely symbolic but serves as the basis for visualizations, rituals, and meditative practices aimed at integrating the diverse aspects of mind into a unified realization of non-dual awareness.

Each of the Five Buddhas corresponds to one of the five aggregates (skandhas), which constitute the basis of personal identity in Buddhist psychology: form, sensation, perception, mental formations, and consciousness. Similarly, each is associated with a specific element (space, water, earth, fire, wind), a direction, a color, a symbolic gesture (mudrā), and one of the Five Wisdoms — transformed aspects of the five primary afflictive emotions. These correspondences form a matrix through which the practitioner can engage the totality of experience and transform ignorance, anger, pride, desire, and jealousy into clarity, compassion, equanimity, discriminating wisdom, and all-accomplishing action.

To summarize all attributes of the Five Tathāgatas within the mandala or matrix, the following layout offers a simplified visual representation:

| Amoghasiddhi (North) Skandha: Mental Formations Element: Air Color: Green Mudrā: Fearlessness Wisdom: All-accomplishing wisdom |

||

| Amitābha (West) Skandha: Perception Element: Fire Color: Red Mudrā: Meditation Wisodm: Discriminating wisdom |

Vairocana (Center) Skandha: Form Element: Space Color: White Mudrā: Teaching Wisdom: Dharmadhātu wisdom |

Akshobhya (East) Skandha: Consciousness Element: Water Color: Blue Mudrā: Earth-touching Wisdom: Mirror-like wisdom |

| Ratnasambhava (South) Skandha: Feeling/Sensation Element: Earth Color: Yellow Mudrā: Giving Wisdom: Wisdom of equality |

Thus, the Five Tathāgatas operate as an integrated symbolic system: a map of transformation, a cosmological model, and a soteriological guide. Their mandalic arrangement allows the practitioner to center themselves within a sacred cosmos and to recognize that all aspects of mind and reality, when purified of delusion, are already expressions of awakened wisdom.

The Five Wisdoms: A framework of enlightened awareness

In the Vajrayāna tradition, each of the Five Tathāgatas embodies a distinct “Wisdom” (jñāna) that emerges when a specific afflictive emotion is transformed through meditative realization. These Five Wisdoms do not represent abstract ideas but facets of awakened mind that are accessible through tantric practice and internal cultivation. They correspond to both psychological states and cosmological principles, serving as a bridge between inner transformation and the structure of enlightened reality.

- Dharmadhātu wisdom (dharmadhātu-jñāna) — Associated with Vairocana, this wisdom arises from the transformation of ignorance or delusion. It perceives the emptiness and interdependence of all phenomena, recognizing the unity of all appearances in the vast field of reality (dharmadhātu).

- Mirror-like wisdom (ādarśa-jñāna) — Embodied by Akṣobhya, this wisdom transforms anger into clear, impartial awareness. Like a mirror, it reflects all phenomena without bias, distortion, or reactivity.

- Wisdom of equality (samatā-jñāna) — Manifest in Ratnasambhava, this wisdom arises from overcoming pride or arrogance. It sees all beings as fundamentally equal in their nature, fostering deep equanimity and non-discrimination.

- Discriminating wisdom (pratyavekṣaṇa-jñāna) — Linked to Amitābha, this wisdom results from transforming desire or attachment. It enables precise and compassionate discernment of the unique characteristics of beings and phenomena, without clinging or aversion.

- All-accomplishing wisdom (kṛty-anuṣṭhāna-jñāna) — Realized through Amoghasiddhi, this wisdom transforms envy and competitiveness into fearless, spontaneous action that benefits all beings. It reflects the enlightened capacity to accomplish tasks without hesitation or egoic interference.

These Five Wisdoms articulate the tantric insight that the very energies that bind us in suffering can become the forces of liberation when recognized and integrated. They provide a comprehensive model for meditative transformation and ethical refinement, central to the

Vairocana: Center and embodiment of dharmadhātu wisdom

Vairocana occupies the central position within the mandala of the Five Tathāgatas and symbolizes the unifying principle of awakened reality. He is regarded as the embodiment of the Dharmadhātu, the all-encompassing sphere of reality, and the source from which the other Tathāgatas emanate. His name, derived from Sanskrit roots meaning “luminous” or “radiating light”, reflects his role as a representation of all-pervading wisdom that illuminates the true nature of things.

In iconography, Vairocana is often depicted seated in full lotus posture on a lion throne, symbolizing majesty and spiritual authority. His hands typically form the Dharmachakra mudrā, the gesture of “turning the wheel of the Dharma”, signifying his function as the universal teacher. In some traditions, especially in East Asia, Vairocana is portrayed with a multi-tiered crown and elaborate adornments, underscoring his transcendent and cosmic dimension. His color is white, representing the purity and integration of all colors, just as his wisdom integrates all aspects of enlightened awareness.

Vairocana embodies the Dharmadhātu Wisdom (dharmadhātu-jñāna), which arises from the transformation of fundamental ignorance or delusion. This wisdom perceives the emptiness of all phenomena, recognizing their interdependence and lack of inherent selfhood. Rather than being a nihilistic emptiness, it is a luminous and spacious awareness in which all experiences arise and dissolve. Vairocana’s associated skandha is form (rūpa), reflecting the transformation of attachment to physical appearance into an understanding of its empty nature.

Philosophically, Vairocana plays a central role in the Yogācāra and Huayan (Chinese: Huáyán) schools of Buddhism. In Yogācāra, he represents the purified aspect of perception beyond subject-object duality, aligning with the doctrine of vijñaptimātra (mind-only). In the Huayan tradition, Vairocana is identified with the cosmic Buddha whose body is identical with the Dharma realm. The Avataṁsaka Sūtra (Huayan Jing), one of the foundational texts of this school, presents Vairocana as both immanent and transcendent — a Buddha whose body is the totality of reality itself, interpenetrated and mutually containing all phenomena.

Thus, Vairocana is not simply one among the Five Tathāgatas, but the axis of their integration: the still point around which the mandala turns. As the central embodiment of Dharmadhātu Wisdom, he affirms the possibility of directly realizing the totality of existence as inherently awakened, radiant, and whole.

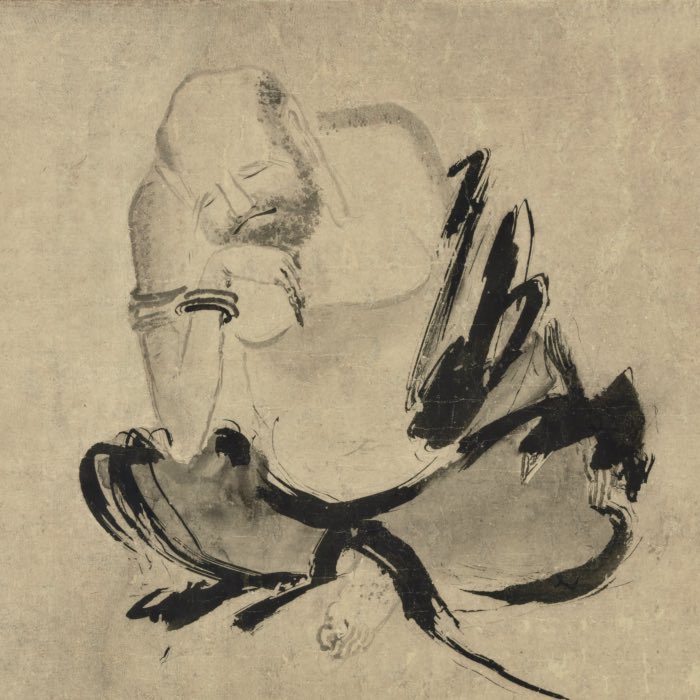

Akshobhya: East and mirror-like wisdom

Positioned in the eastern quadrant of the mandala, Akshobhya (“Immovable One”) embodies stability, clarity, and the fearless equanimity of the awakened mind. His name reflects his defining characteristic: an unwavering, unshakable mind that does not react to disturbing emotions. He serves as the archetype of steadfast mindfulness, especially in the face of anger and aversion.

In iconography, Akshobhya is typically depicted as deep blue in color, symbolizing the depth and clarity of a perfectly still ocean. He holds a vajra (diamond-thunderbolt) in his left hand, symbolizing indestructible truth and power, and his right hand touches the earth in the bhūmisparśa mudrā — a gesture associated with the moment of the historical Buddha’s awakening. This mudrā emphasizes grounding, calling the earth to witness the clarity of mind that triumphs over illusion.

Akshobhya is associated with the Mirror-like Wisdom (ādarśa-jñāna), which arises from the transformation of anger. Just as a mirror reflects all things impartially and without distortion, this wisdom sees things as they truly are, without the distortion caused by emotional reactivity. It brings a calm, clear knowing that does not cling or push away, reflecting reality with precision and neutrality.

This Tathāgata corresponds to the skandha of consciousness (vijñāna), representing the shift from grasping awareness to a pure, receptive presence. In practice, Akshobhya symbolizes the possibility of transforming volatile mental energy into insight and equanimity. His role is particularly important in tantric meditation systems that aim to transmute the energy of afflictive emotions into luminous wisdom.

As a figure of meditative resolve, Akshobhya has also been the focus of independent cultic worship, particularly in East and Central Asia. Devotees invoke him not only to purify anger, but to cultivate psychological resilience and the power to withstand spiritual adversity. Thus, Akshobhya stands as the guardian of the eastern gate of the enlightened mind, a protector whose presence anchors clarity in the midst of confusion.

Amitābha: West and discriminating wisdom

Amitābha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, presides over the western direction of the mandala and represents the refined awareness known as Discriminating Wisdom (pratyavekṣaṇa-jñāna). He embodies the transformation of desire and attachment into clear, compassionate discernment — the capacity to recognize and appreciate the uniqueness of each phenomenon without clinging.

Iconographically, Amitābha is depicted in deep red, symbolizing the power of compassion and the transformative energy of desire. He is typically shown seated in meditation posture, his hands resting in the dhyāna mudrā (gesture of meditation), often holding a lotus or a begging bowl. This serene presentation reflects his association with inward clarity and the contemplative cultivation of awareness. The red color also signifies warmth and love, i.e., emotions that, when untainted by craving, become forms of liberated, non-attached care for others.

Amitābha’s wisdom corresponds to the skandha of perception (samjñā), the mental function by which we differentiate and categorize sensory input. In unawakened consciousness, perception is colored by grasping and aversion, leading to craving and the illusion of separateness. Discriminating Wisdom does not erase distinctions but sees them clearly and compassionately, free of fixation. It is the wisdom that allows the practitioner to perceive the distinct qualities of beings and phenomena without falling into dualistic attachment.

Amitābha’s role is also central in the devotional context of Pure Land Buddhism, where he is the presiding Buddha of the Western Paradise (Sukhāvatī). This celestial realm is envisioned as a realm of optimal conditions for Dharma practice, free from the hindrances of our world. Devotees cultivate faith in Amitābha and recite his name (nembutsu or nianfo) with the aspiration to be reborn in this realm and there attain awakening. In this devotional tradition, Amitābha symbolizes both the salvific power of other-directed compassion and the internal potential to purify desire into wisdom.

Through both tantric and Pure Land lenses, Amitābha represents the deep possibility of transforming the energies of longing and emotional attachment into lucid, benevolent awareness. His westward gaze and glowing presence remind practitioners that the path of awakening includes not only transcending craving, but honoring the individuality of beings with discerning love.

Ratnasambhava: South and equality wisdom

Ratnasambhava, the Buddha of the southern direction, embodies the Wisdom of Equality (samatā-jñāna), which arises from the transformation of pride, arrogance, and judgment into profound equanimity and generosity. His name means “Origin of Jewels,” and he represents the boundless abundance of the awakened mind, which gives without attachment and recognizes all beings as inherently equal in their potential for enlightenment.

Iconographically, Ratnasambhava is associated with the color yellow, symbolizing nourishment, stability, and fecundity. He is often depicted seated on a lotus and lion throne, radiating warmth and generosity, with his right hand extended in the varada mudrā, the gesture of giving. This gesture expresses his role as the dispenser of spiritual and material riches, not in a literal sense, but as a symbol of unconditional benevolence and inner wealth.

Ratnasambhava corresponds to the skandha of sensation or feeling (vedanā), which involves the initial affective tone of experience: pleasure, pain, or neutrality. In ordinary consciousness, this skandha often becomes a trigger for grasping or aversion, reinforcing a reactive and ego-centered worldview. When transformed by insight, it reveals a deeper capacity to receive experience without partiality or self-centered filtering.

The wisdom of Equality does not suggest sameness, but rather the insight that all beings possess the same essential nature and are equally deserving of respect, dignity, and compassion. It cuts through hierarchical thinking, status anxiety, and the subtle habits of comparison that sustain pride and division. Through the lens of this wisdom, distinctions between self and other, superior and inferior, dissolve into a field of mutual recognition and respect.

In Vajrayāna practice, Ratnasambhava is invoked to cultivate generosity, humility, and non-discriminating compassion. He plays a particularly important role in rituals aimed at overcoming class or caste bias, and in the training of the mind to respond to all beings with impartial warmth. His southward orientation within the mandala symbolizes groundedness and openness, inviting practitioners to rest in the stable radiance of equanimity.

As such, Ratnasambhava embodies the alchemical transformation of pride into luminous balance. His presence reminds practitioners that equality is not merely a social or ethical stance, but a profound realization of the sameness of all beings in their shared Buddha-nature.

Amoghasiddhi: North and all-accomplishing wisdom

Amoghasiddhi, the Buddha of the northern direction, embodies the All-Accomplishing Wisdom (kṛty-anuṣṭhāna-jñāna), which arises from the transformation of envy and fear of inefficacy into courageous, effective action. His name means “Unfailing Success” or “Infallible Accomplishment,” and he personifies the capacity of enlightened beings to act in the world with clarity, confidence, and selfless purpose.

Visually, Amoghasiddhi is represented in green, a color symbolizing vitality, dynamic movement, and transformative energy. He is typically shown performing the abhaya mudrā, the gesture of fearlessness, with his right hand raised in a protective and empowering stance. This mudrā communicates his role as a source of spiritual protection and encouragement for practitioners who face uncertainty or doubt. In some representations, he holds a double vajra (viśvavajra), symbolizing the power of enlightened action in all directions.

Amoghasiddhi is linked to the skandha of mental formations (saṃskāra), which encompass volitional impulses, karmic tendencies, and the dynamics of intention. In unawakened experience, this skandha often gives rise to envy, insecurity, or paralysis in the face of action. When transformed through practice, it becomes the ground for unimpeded engagement, enabling compassionate activity free from egoic interference or hesitation.

The All-Accomplishing Wisdom that Amoghasiddhi represents is not about striving or achievement in a conventional sense, but rather the spontaneous and skillful expression of enlightened energy. It reflects the realization that awakened activity arises naturally when there is no clinging to self, no fear of failure, and no competitive striving. Such action is “effortless” in the sense that it flows from insight rather than reactive desire.

In tantric visualization practices, Amoghasiddhi’s presence supports the practitioner’s development of fearless compassion and decisive ethical conduct. He is particularly revered in rituals aimed at removing obstacles, dissolving karmic blockages, and cultivating effective means (upāya) in compassionate engagement with the world. His association with the wind element emphasizes flexibility, speed, and the capacity to permeate all domains of experience.

Thus, Amoghasiddhi represents the fruition of tantric practice in the form of liberative activity. He reminds practitioners that wisdom is not merely contemplative, but also active — manifesting as fearless compassion that transforms both self and world.

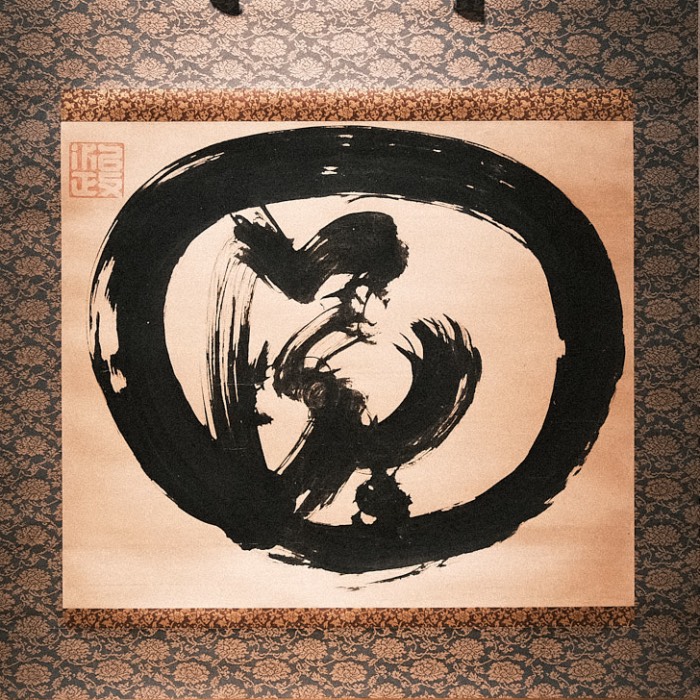

Integrative role in Tantra and practice

The Five Tathāgatas are not simply abstract principles or mythic figures; they function as essential components of tantric Buddhist practice, serving as both meditative anchors and catalysts for profound psychological transformation. In Vajrayāna ritual and sādhanā, these Buddhas are encountered through visualization, mantra recitation, symbolic offerings, and empowerment rituals. Each Tathāgata becomes a gateway through which practitioners engage specific energies of the mind and transmute afflictive tendencies into awakened qualities.

In meditation, practitioners may visualize the Five Tathāgatas seated within a mandala, their colors, mudrās, and attributes precisely imagined to align with their corresponding wisdoms and skandhas. This process is not merely imaginative but a method of internalizing their transformative presence. By identifying with the central figure, typically Vairocana, and integrating the directional Buddhas, the practitioner enacts the non-dual realization that the enlightened qualities they revere already lie latent within their own mindstream.

Rituals of empowerment (Sanskrit: abhiseka) often confer the blessings of the Five Tathāgatas through symbolic anointment, visualization sequences, and mantra transmission. These empowerments function as initiations into deeper layers of tantric practice and affirm the practitioner’s capacity to embody these wisdoms. The mandala, thus, becomes both a symbolic cosmos and a mirror of the purified psyche.

On a psychological level, the system of the Five Buddhas offers a comprehensive model for inner alchemy. Instead of suppressing emotions such as anger, pride, or desire, Vajrayāna practice recognizes them as energetic potentials that, when understood and integrated, transform into insight, generosity, or discriminating awareness. The Five Tathāgatas thus model a radical approach: transformation rather than rejection, integration rather than avoidance.

Soteriologically, they represent the total unfolding of Buddha-nature into five differentiated yet inseparable aspects of awakening. Their non-dual interrelation affirms that enlightenment is not a static goal but a dynamic, multifaceted realization. The mandala practice culminates in the dissolution of distinctions: the five become one, and the one refracts into five — a continuous interplay of unity and diversity within awakened mind.

In sum, the Five Tathāgatas are not passive icons but active frameworks of realization. They provide both a spiritual cartography and a method of direct engagement, revealing how the path to liberation is already inscribed within the structure of the mind itself.

Conclusion

The Five Tathāgatas present a highly integrated system that spans cosmological, ethical, meditative, and philosophical dimensions of Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism. Emerging from the concept of the Adibuddha as the unconditioned ground of awakened awareness, these five archetypal Buddhas articulate a structured and transformative vision of the awakened mind.

As a cosmological framework, they map the sacred space of the mandala, aligning cardinal directions, elements, colors, and aggregates into a coherent symbolic system. Each Buddha represents a specific mode of wisdom, and their spatial and symbolic interrelations provide the practitioner with a visual and conceptual model of the enlightened universe. This cosmology is not external to the practitioner but mirrors the inner structure of mind and perception.

Ethically and psychologically, the Five Tathāgatas serve as models of transformation. Each corresponds to one of the five principal afflictive emotions — ignorance, anger, pride, desire, and envy — which are not rejected but transmuted through contemplative practice into wisdom. This system reflects a central tenet of tantric Buddhism: that the path to liberation is not found in negation or repression but in recognition, integration, and redirection. It asserts that the energies of delusion themselves can become the forces of awakening.

Soteriologically, the Five Tathāgatas represent differentiated expressions of Buddha-nature, latent in all beings but activated through practice. Their ritual invocation, visualization, and embodiment guide practitioners from conceptual understanding to direct experiential realization. Ultimately, they serve as both path and goal: the practitioner visualizes them not as external deities but as mirrors of their own inherent clarity, equanimity, compassion, and efficacy.

In Vajrayāna practice, the Five Tathāgatas remain central to both personal and communal ritual life. Their symbolism shapes empowerments, sādhanās, mandalas, and philosophical expositions. Moreover, their enduring relevance lies in the dynamic way they express non-duality: the inseparability of form and emptiness, saṃsāra and nirvana, method and wisdom. This integrative vision continues to influence both classical doctrine and contemporary Buddhist thought.

Thus, the Five Tathāgatas are not merely historical constructions or religious icons. They are multidimensional tools for personal transformation, doctrinal articulation, and cosmological imagination. By engaging with them, practitioners access a comprehensive system for understanding and enacting the path to Buddhahood in both theory and practice.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments