Dharma: The universal law in Buddhism

The term Dharma occupies a central place in Buddhism, representing both the universal law that governs reality and the body of teachings provided by the Buddha. Dharma literally translates as “that which supports” or “that which holds together”, reflecting its foundational role in Buddhist philosophy and practice. Within Buddhism, Dharma is understood as the nature of reality itself, the truth the Buddha realized upon his awakening, and the instructions he provided to guide practitioners toward liberation. In this post, we explore essential components of the Buddhist understanding of the Dharma, illustrating how it represents the universal law governing existence and provides the framework for the Buddhist worldview.

Wheel of the Buddhist Law (Jap.: rinpō; Pāli: dharmacakra; Sanskrit: dharmachakra), Japan, late 13th century, Kamakura period (1185–1333), gilt bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The dharmachakra is a common symbol of the Dharma, embodying the Buddha’s teachings and the path to enlightenment. In Buddhist tradition, the phrase “turning the wheel of the law” signifies Siddhartha Gautama’s act of teaching, setting the Dharma ‘in motion’. The eight spokes and eight corners represent the moral principles of the Noble Eightfold Path, while the central section, adorned with a lotus flower bearing eight petals, evokes purity and spiritual awakening. The wheel hub usually features three swirling shapes symbolizing the Three Jewels of Buddhism: the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha (not present in this wheel; see example at the end of this post). However, the number three has various interpretations in Buddhism, including the Three Marks of Existence, the Three Poisons, and the Threefold Training. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Artꜛ (license: public domainꜛ)

Wheel of the Buddhist Law (Jap.: rinpō; Pāli: dharmacakra; Sanskrit: dharmachakra), Japan, late 13th century, Kamakura period (1185–1333), gilt bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The dharmachakra is a common symbol of the Dharma, embodying the Buddha’s teachings and the path to enlightenment. In Buddhist tradition, the phrase “turning the wheel of the law” signifies Siddhartha Gautama’s act of teaching, setting the Dharma ‘in motion’. The eight spokes and eight corners represent the moral principles of the Noble Eightfold Path, while the central section, adorned with a lotus flower bearing eight petals, evokes purity and spiritual awakening. The wheel hub usually features three swirling shapes symbolizing the Three Jewels of Buddhism: the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha (not present in this wheel; see example at the end of this post). However, the number three has various interpretations in Buddhism, including the Three Marks of Existence, the Three Poisons, and the Threefold Training. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Artꜛ (license: public domainꜛ)

"Dharma" vs. "Dharmas"

In the context of Buddhism, the term dharma can refer to both the universal law and the teachings of the Buddha. However, it is important to note that dharma in plural, dharmas, is often used to refer to the individual phenomena or constituents of experience. In Buddhist philosophy — especially within the Abhidharma tradition — dharmas are the fundamental building blocks of reality. They include physical and mental events, sensory experiences, intentions, and mental states. Each dharma is conditioned, impermanent, and devoid of self. In Buddhist thinking, understanding the nature and interaction of these dharmas is essential for gaining insight into the nature of existence and progressing on the path to liberation.

What is the Dharma?

Dharma (Sanskrit; Pāli: Dhamma) is a profound and multifaceted term central to Indian philosophy, spirituality, and religious practice. Broadly speaking, Dharma is the universal principle or natural order governing the cosmos, life, and morality. It encompasses ethical behavior, societal duties, natural laws, and spiritual truth. Dharma holds together the universe, sustaining the cosmic balance and guiding human behavior towards harmony with the natural and social worlds. It provides the foundational principles upon which ethical conduct, personal responsibility, and cosmic order are built, influencing not only religious practices but also societal structures, law, and governance.

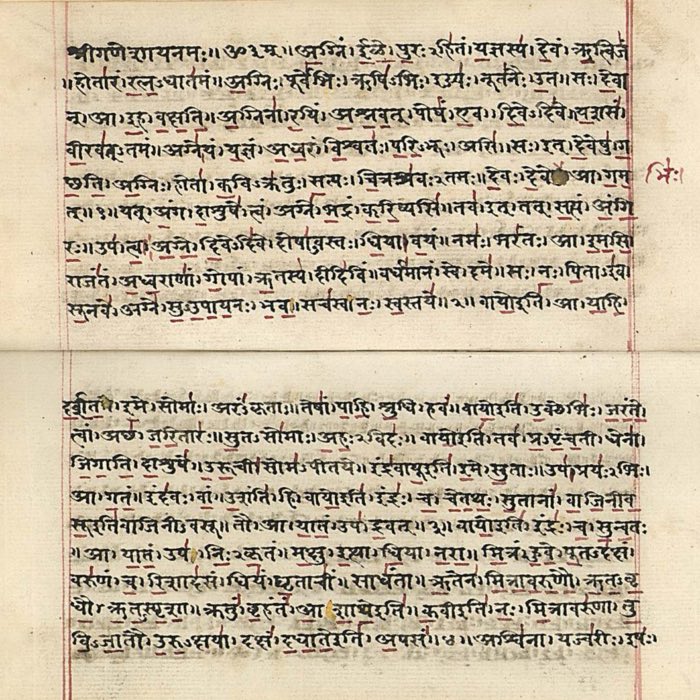

Historical development of Dharma in Indian Philosophy

Historically, Dharma first prominently emerged within the Vedic traditions as a foundational concept tied closely to the idea of Rta — cosmic order or universal truth. Initially, Dharma revolved largely around correct performance of rituals and social obligations necessary for maintaining harmony between humans, nature, and the divine. As Vedic society evolved, particularly during the Upanishadic period, the interpretation of Dharma shifted, increasingly emphasizing internal morality and metaphysical insights over ritualistic practices. The Upanishads introduced deeper philosophical contemplation, identifying Dharma more with the individual’s pursuit of spiritual knowledge and ethical self-realization rather than solely external rituals and duties.

During the era of the Epics, particularly within the Mahabharata and Ramayana (roughly 400 BCE to 400 CE), and subsequently codified in texts known as the Dharmashastras (such as Manusmriti), Dharma significantly expanded its scope and complexity. In these texts, Dharma became intricately tied to social order, ethical conduct, and personal duty (svadharma), meticulously detailing roles and responsibilities based on caste (varna), stage of life (ashrama), and personal circumstance. The Mahabharata and Ramayana vividly illustrate Dharma through narratives that explore moral dilemmas, righteous conduct, and the consequences of adhering to or deviating from Dharma.

By the time Siddhartha Gautama emerged, philosophical discourse in India was becoming increasingly diverse, marked by the rise of various Shramana movements. These ascetic traditions challenged the dominance of ritualistic Brahmanism, emphasizing personal ethical conduct, introspection, and direct spiritual experience over external rituals. Within this dynamic environment, characterized by intense debates on morality, spiritual realization, and the nature of reality, Siddhartha Gautama introduced his revolutionary interpretation of Dharma, significantly reshaping its meaning and practice.

Buddhist interpretation and development of Dharma

Building on the intense philosophical debates of his time, Siddhartha Gautama fundamentally redefined Dharma, shifting it away from external obligations dictated by social and religious structures toward a path centered on direct insight and personal transformation. He rejected the rigid ritualism of Brahmanical traditions, emphasizing instead that Dharma was not an external duty imposed by cosmic order but an experiential truth to be realized through wisdom, ethical living, and disciplined meditation.

Siddhartha’s interpretation of Dharma introduced a radical departure from prevailing views. Rather than reinforcing caste-based obligations and sacrificial rites, he framed Dharma as a universal principle accessible to all, regardless of social status. He emphasized that suffering (dukkha) arises not from failing to perform prescribed duties but from ignorance and attachment. True Dharma, he taught, is discovered through direct insight into the impermanent and selfless nature of reality.

Thus, Buddhism transformed Dharma from an externally imposed societal structure into an internalized, experiential path of self-discovery, ethical cultivation, and meditative discipline, all aimed at breaking the cycle of suffering (saṃsāra) and achieving liberation (nirvana).

Cosmological dimension of Dharma in Buddhism

Beyond personal ethics and spiritual practice, Dharma in Buddhism also encompasses a profound cosmological dimension. It is not merely a moral guideline but the fundamental law that governs the fabric of existence itself. In Buddhist cosmology, Dharma is the sustaining principle behind the universe’s continuous cycles of arising and dissolution. Unlike the fixed, divinely ordained order found in some Brahmanical traditions, Buddhism portrays Dharma as an ever-unfolding, dynamic reality.

According to Buddhist teachings, the cosmos operates in vast cycles of creation, duration, destruction, and renewal, within which all beings are caught in the repetitive cycle of saṃsāra — birth, death, and rebirth — governed by the law of karma (moral causation). Every action, thought, and intention influences this cosmic cycle, reinforcing or alleviating suffering. In this way, Dharma is not just an impersonal force but an interactive system where ethical conduct plays a crucial role in shaping reality.

Furthermore, Buddhist cosmology envisions multiple realms of existence, from heavenly realms inhabited by celestial beings to suffering-laden lower realms. These realms are not eternal but transient states dictated by karma and Dharma. Unlike Brahmanical cosmology, where divine beings enforce cosmic order, Buddhism teaches that Dharma operates as a self-regulating principle, independent of divine intervention. Thus, understanding Dharma is essential for navigating saṃsāra and ultimately attaining liberation (nirvana), where one transcends the cycle of conditioned existence altogether.

By linking the cosmic order with individual moral responsibility, Buddhism presents a view in which Dharma is both the law of nature and the key to personal transformation. It emphasizes that by aligning one’s actions with Dharma, individuals not only progress toward enlightenment but also contribute to the greater harmony of existence itself.

Principles in the Dharma

With Dharma forming the foundation of Buddhist thought, it is essential to understand its key principles and how they guide to liberation. Buddhism does not present Dharma as a static doctrine but as an evolving truth that explains the nature of existence and suffering. The following principles – all integral part of the Dharma – illustrate why suffering arises, how it is perpetuated, and what steps lead to its cessation. Together, they form the practical and philosophical core of Buddhist teachings and worldview, presenting Dharma as both the universal truth that governs existence and the path to liberation.

The Three Marks of Existence

The Dharma clarifies reality through three essential characteristics, known as the Three Marks of Existence (Sanskrit: trilaksana; Pāli: tilakkhana). These fundamental principles describe the nature of all conditioned phenomena and provide insight into why suffering arises and how liberation is possible:

- Impermanence (anicca): Everything in existence is constantly changing, transient, and in flux. Nothing remains static, and all things — including thoughts, emotions, relationships, and material conditions — undergo continuous transformation. Recognizing impermanence allows one to develop detachment and avoid clinging to fleeting experiences.

- Suffering (dukkha): Due to impermanence and craving, existence inevitably involves suffering or dissatisfaction. Dukkha extends beyond physical pain and emotional distress to include the subtle unease caused by the transient nature of all experiences. Even joyful moments are tinged with suffering because they are temporary and inevitably lead to change or loss.

- No-self (anatta): There is no permanent, unchanging self or soul behind experiences. The notion of a stable, independent identity is an illusion created by the interplay of the Five Aggregates (see below). By understanding anatta, one can overcome attachment to the ego and recognize the interconnected, ever-changing nature of existence.

These Three Marks of Existence provide the foundation for the Buddhist analysis of reality and guide practitioners toward relinquishing attachment, developing insight, and progressing on the path to liberation.

Dukkha: The core problem of existence

The Buddhist path to liberation begins with recognizing dukkha, usually translated as suffering, dissatisfaction, or unease. As both one of the Three Marks of Existence and the first of the Four Noble Truths, dukkha lies at the heart of Buddhist concern — not only as an inherent characteristic of conditioned reality but as the central problem to be overcome. It pervades human experience, manifesting in various forms: disappointment when desires go unfulfilled, sorrow at loss, anxiety about change, and even the subtle dissatisfaction that lingers even in moments of happiness. More than just physical pain or emotional distress, dukkha reflects the fundamental instability of all conditioned experiences.

Buddhism identifies dukkha as the fundamental existential challenge, initiating the quest to understand its origins and cessation. Unlike other philosophical traditions that may view suffering as incidental or external, Buddhism treats dukkha as inherent to all conditioned existence. Even pleasurable experiences are marked by dukkha because they are impermanent and ultimately lead to craving and attachment, which in turn generate more suffering.

The option Buddhism one provides for addressing dukkha is not to deny or escape it but to understand its roots and transform the mind’s relationship to it. By fully grasping the pervasive nature of dukkha, one can begin to cultivate insight into its causes and pursue the path toward its cessation, which is the foundation of Buddhist practice.

Tanhā

Tanhā (craving or thirst) is identified in Buddhism as the primary cause of suffering. It refers to the relentless craving for sensory pleasures, existence, or even non-existence. This insatiable desire fuels attachment and perpetuates saṃsāra — the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. Unlike mere desires or aspirations, tanhā is an intense, compulsive longing that binds beings to suffering by reinforcing ignorance and attachment.

Because tanhā is fueled by ignorance (avidyā) and the illusion of a permanent self, it serves as the driving force behind clinging (upādāna), which further entangles beings in saṃsāra. Overcoming tanhā is essential for breaking the cycle of suffering. The Buddhist path offers a solution through wisdom (prajñā), ethical conduct (sīla), and meditative discipline (samādhi), which help practitioners recognize craving, detach from it, and cultivate contentment and inner peace.

Upādāna

Closely linked to tanhā, upādāna (clinging or grasping) is the intensified attachment that arises from craving and solidifies suffering. While tanhā represents the initial thirst for pleasure, existence, or annihilation, upādāna is the act of clinging tightly to these desires, reinforcing the cycle of saṃsāra.

Upādāna strengthens attachment and reinforces the illusion of control over impermanent experiences, further entangling beings in suffering. Overcoming upādāna requires deep insight into the impermanent and selfless nature of existence, cultivated through meditation, ethical living, and wisdom. By recognizing and releasing clinging, practitioners move closer to true liberation.

The Five Aggregates: The components of the self

Buddhism presents the self not as a singular, unchanging entity but as a dynamic process composed of Five Aggregates (skandhas). These aggregates interact to create the illusion of a stable identity, yet each is impermanent and devoid of inherent selfhood. Understanding the Five Aggregates is central to the Buddhist insight into anatta (no-self), as it dismantles the illusion of a permanent soul or ego.

The Five Aggregates are:

- Form (rūpa): The physical body and sensory organs, including everything material that constitutes our bodily existence. This aggregate allows interaction with the external world through sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch.

- Feeling (vedanā): The sensations that arise from sensory contact, categorized as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. These sensations contribute to craving and aversion, influencing attachment and suffering.

- Perception (saññā): The recognition and interpretation of sensory input. Perception allows the mind to label experiences, forming concepts and mental associations.

- Mental Formations (saṅkhāra): Thoughts, emotions, volitions, and intentions that shape behavior. This aggregate includes karmic tendencies and habitual patterns that reinforce attachments and aversions.

- Consciousness (viññāṇa): The awareness of sensory and mental objects, forming the basis for experience. Consciousness arises dependent on the other aggregates and does not exist independently.

The Buddhist analysis of the Five Aggregates reveals that the sense of “I” or “self” is merely a constructed phenomenon arising from these constantly changing processes. Clinging to any of these aggregates as “me” or “mine” leads to suffering, as they are impermanent and subject to change. Liberation involves seeing through this illusion, cultivating detachment, and ultimately realizing anatta — the absence of a fixed, independent self.

The Three Poisons

At the heart of Buddhist teachings on suffering lies the doctrine of The Three Poisons (akusala mūla) — greed (lobha), hatred (dosa), and delusion (moha). These three defilements are considered the root causes of suffering and the primary forces that keep beings trapped in saṃsāra, the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. The Three Poisons are deeply embedded in human consciousness, shaping actions, perceptions, and desires:

- Greed (lobha)

- Greed is an insatiable craving for sensory pleasures, material wealth, power, or even spiritual attainments. It manifests in attachment, desire, and the inability to find contentment. Rooted in the illusion of permanence, greed leads individuals to seek lasting satisfaction in impermanent things, resulting in frustration and suffering.

Buddhist practice counters greed through generosity (dāna), detachment, and the cultivation of contentment. By recognizing the transient nature of all things, one can loosen attachment and cultivate an attitude of non-clinging. - Hatred (dosa)

- Hatred arises from aversion, anger, resentment, and ill will. It leads to conflict, violence, and the rejection of unpleasant experiences or individuals. When driven by hatred, people react impulsively, causing harm to themselves and others

The antidote to hatred is loving-kindness (mettā) and compassion (karuṇā). Buddhist teachings encourage practitioners to cultivate patience, forgiveness, and empathy, transforming anger into understanding and goodwill. - Delusion (moha)

- Delusion refers to ignorance and misunderstanding of reality. It is the failure to see things as they truly are, particularly regarding impermanence (anicca), suffering (dukkha), and the absence of a permanent self (anatta). Delusion clouds judgment and perpetuates attachment and aversion.

The remedy for delusion is wisdom (prajñā), developed through study, reflection, and meditative insight. By cultivating right understanding and awareness, practitioners dismantle ignorance and gain clarity into the nature of existence.

Together, the Three Poisons form the foundation of karmic conditioning, influencing thoughts, speech, and actions. They fuel unwholesome behaviors that reinforce suffering and perpetuate rebirth. The Buddhist path, particularly the Noble Eightfold Path, is designed to weaken and ultimately eradicate these defilements, leading to liberation (nirvāṇa).

By recognizing and transforming greed, hatred, and delusion, practitioners can break free from the cycle of suffering and cultivate wholesome qualities that support spiritual growth and awakening. The Three Poisons serve as a diagnostic tool for understanding the root causes of suffering and provide a roadmap for overcoming them through ethical living, meditation, and wisdom.

Dependent origination: The chain of causation

One of the most profound and intricate teachings within Buddhism is the doctrine of dependent origination (Paṭicca-Samuppāda). This principle explains the interconnected and conditioned nature of existence, illustrating how suffering arises and perpetuates itself. It asserts that all phenomena arise due to causes and conditions, rejecting the idea of an independent, unchanging self or absolute reality.

Dependent origination is often depicted as a cycle of twelve interdependent links, each conditioning the next in a continuous chain of causation. These twelve links describe how ignorance and craving create suffering and rebirth:

- Ignorance (avidyā) – The fundamental misunderstanding of reality, particularly regarding impermanence, suffering, and no-self.

- Volitional Formations (saṅkhāra) – Karmic formations, or intentional actions shaped by ignorance, leading to future consequences.

- Consciousness (viññāṇa) – The arising of awareness conditioned by past karmic actions.

- Name and Form (nāma-rūpa) – The development of mental and physical components in existence.

- Six Sense Bases (saḷāyatana) – The faculties of perception: eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind.

- Contact (phassa) – The interaction between the senses and external objects.

- Feeling (vedanā) – The sensations experienced as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral.

- Craving (tanhā) – The thirst for sensory pleasure, existence, or annihilation.

- Clinging (upādāna) – The intensification of craving, leading to attachment and identification with objects, experiences, and concepts of self.

- Becoming (bhava) – The formation of karmic imprints that determine future existence.

- Birth (jāti) – The arising of a new existence conditioned by past karma.

- Aging and Death (jarāmaraṇa) – The inevitable cycle of decay, suffering, and rebirth.

Since each link arises due to the preceding condition, the cycle can be broken by removing ignorance. By cultivating wisdom (prajñā), ethical conduct (sīla), and meditative awareness (samādhi), one weakens craving and attachment, ultimately disrupting the cycle of rebirth.

Insight into dependent origination is regarded as a critical step toward achieving Nirvāṇa, as it allows practitioners to understand the impermanent and interdependent nature of existence, freeing them from the illusion of self and the endless cycle of suffering.

The Four Noble Truths: The foundation of Buddhist teachings

At the core of the Buddha’s teachings lies the Four Noble Truths (Cattāri Ariyasaccāni), a framework that provides both a diagnosis of human suffering and a path to its cessation. They consist of dukkha (suffering) and Samudaya (the origin of suffering) – which we have already discussed – as well as nirodha (the cessation of suffering) and magga (the path to the cessation of suffering). The Four Noble Truths encapsulate the essential insight that led Siddhartha Gautama to awakening and form the foundation of all Buddhist traditions.

1. The truth of suffering (dukkha)

The first noble truth states that existence is marked by suffering, dissatisfaction, and impermanence. All conditioned phenomena are subject to change, and as a result, suffering is unavoidable. This includes:

- Physical suffering: Birth, aging, illness, and death.

- Emotional suffering: Loss, separation, failure, and dissatisfaction.

- Existential suffering: The pervasive sense of unease resulting from impermanence and the illusion of self.

Understanding dukkha is the first step in transcending suffering rather than avoiding or denying it.

2. The truth of the origin of suffering (samudaya)

The second noble truth identifies the cause of suffering as craving (tanhā) and attachment (upādāna). Craving manifests in three forms:

- Craving for sensory pleasures (kāma-tanhā) – The pursuit of material gratification and sensual indulgence.

- Craving for existence (bhava-tanhā) – The attachment to identity, continuity, and a sense of self.

- Craving for non-existence (vibhava-tanhā) – The desire for annihilation or escape from suffering.

These cravings are fueled by ignorance (avidyā), which distorts perception and sustains the cycle of saṃsāra.

3. The truth of the cessation of suffering (nirodha)

The third noble truth proclaims that liberation from suffering is possible. By extinguishing craving and attachment, suffering ceases, leading to nirvāṇa — the state of complete freedom, peace, and unconditioned existence. Nirvāṇa is not a place but a state of being free from clinging and delusion.

4. The truth of the path to the cessation of suffering (magga)

The fourth noble truth presents the Noble Eightfold Path as the method for overcoming suffering and attaining liberation. It consists of three key areas:

- Wisdom (prajñā): Right View, Right Intention.

- Ethical Conduct (sīla): Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood.

- Mental Discipline (samādhi): Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, Right Concentration.

By following this path, one gradually weakens the Three Poisons, cultivates insight, and attains a state of inner freedom.

The Noble Eightfold Path

The Noble Eightfold Path (Ariyo Aṭṭhaṅgiko Maggo) is the practical framework that enables practitioners to overcome suffering and attain liberation. It represents the ethical and mental discipline required to weaken the Three Poisons, uproot ignorance, and cultivate wisdom. The path is divided into three core areas: wisdom (prajñā), ethical conduct (sīla), and mental discipline (samādhi), each comprising specific steps that interconnect and reinforce one another:

Wisdom (prajñā)

- Right View (sammā-diṭṭhi) – Understanding the Four Noble Truths, impermanence, no-self, and the law of karma. This correct understanding guides the entire path.

- Right Intention (sammā-saṅkappa) – Cultivating intentions of renunciation, goodwill, and harmlessness, replacing greed, hatred, and delusion.

Ethical conduct (sīla)

- Right Speech (sammā-vācā) – Speaking truthfully, avoiding lies, harsh words, divisive speech, and idle chatter.

- Right Action (sammā-kammanta) – Acting ethically by abstaining from killing, stealing, and harmful behavior.

- Right Livelihood (sammā-ājīva) – Earning a living in a way that does not cause harm to oneself or others (e.g., avoiding professions tied to exploitation, violence, or dishonesty).

Mental discipline (samādhi)

- Right Effort (sammā-vāyāma) – Cultivating wholesome mental states while abandoning unwholesome thoughts and emotions.

- Right Mindfulness (sammā-sati) – Developing present-moment awareness through meditation and mindfulness of body, feelings, mind, and mental phenomena.

- Right Concentration (sammā-samādhi) – Attaining deep meditative absorption (jhana) through focused and disciplined mental training, leading to profound insight.

The path as a holistic practice

Unlike a linear progression, the Noble Eightfold Path is often described as an interwoven process, where progress in one area strengthens the others. Practicing ethical conduct creates the stability necessary for meditation, while meditative insight deepens wisdom. By cultivating these principles, practitioners gradually dissolve suffering and move toward nirvāṇa — the cessation of craving, attachment, and ignorance.

Nirvāṇa: The cessation of suffering

Nirvāṇa, often described as the ultimate ‘goal’ of Buddhist practice, refers to the cessation of suffering and the end of cyclic existence (saṃsāra). It is the state in which craving (tanhā), attachment (upādāna), and ignorance (avidyā) are completely extinguished, leading to a profound realization of peace, wisdom, and liberation.

The term nirvāṇa (Sanskrit; Pāli: nibbāna) means “extinguishing” or “blowing out”, symbolizing the extinguishing of the fires of greed, hatred, and delusion. Unlike in many religious traditions that envision a paradise or an afterlife, nirvāṇa is not a place or a heaven but a state of being beyond all conditioned existence. It is the direct realization of the unconditioned nature of reality, free from suffering and the cycle of rebirth.

Nirvāṇa is attained through wisdom (prajñā), ethical conduct (sīla), and mental discipline (samādhi), cultivated through the Noble Eightfold Path. By dismantling the illusion of self (anatta) and seeing through the conditioned nature of reality, practitioners gradually loosen their attachments and cravings, leading to the cessation of suffering.

Compassion and loving-kindness

A fundamental aspect of Buddhist practice is the cultivation of compassion (karuṇā) and loving-kindness (mettā). These qualities are essential for counteracting the Three Poisons (greed, hatred, and delusion) and serve as the ethical foundation for Buddhist thought and action:

- Mettā: unconditional loving-kindness

- Mettā refers to an active, boundless love that extends to all beings, regardless of their actions or circumstances. It is cultivated through practices such as Mettā Bhāvanā, a meditation that systematically develops loving-kindness by sending goodwill to oneself, loved ones, neutral people, and even perceived enemies. Practicing mettā dissolves hostility and fosters a deep sense of interconnectedness and empathy.

- Karuṇā: Compassion as the response to suffering

- Karuṇā is the empathetic response to the suffering of others, accompanied by a sincere wish to alleviate it. Unlike pity, which may create a sense of separation, karuṇā arises from deep insight into the shared nature of suffering. It is the foundation of the Bodhisattva ideal in Mahāyāna Buddhism, where practitioners vow to liberate all beings before attaining final Nirvāṇa themselves.

Compassion and loving-kindness are not mere emotional states but integral components of wisdom. They prevent spiritual practice from becoming detached or self-centered, ensuring that insight leads to actions that benefit others. The Noble Eightfold Path emphasizes ethical conduct, and genuine compassion transforms moral discipline into a spontaneous expression of awakened understanding.

By cultivating mettā and karuṇā, practitioners develop equanimity (upekṣā), the ability to maintain balance and serenity amid life’s fluctuations. Together, these qualities form the ethical and emotional backbone of the Buddhist path, harmonizing personal liberation with the well-being of all beings.

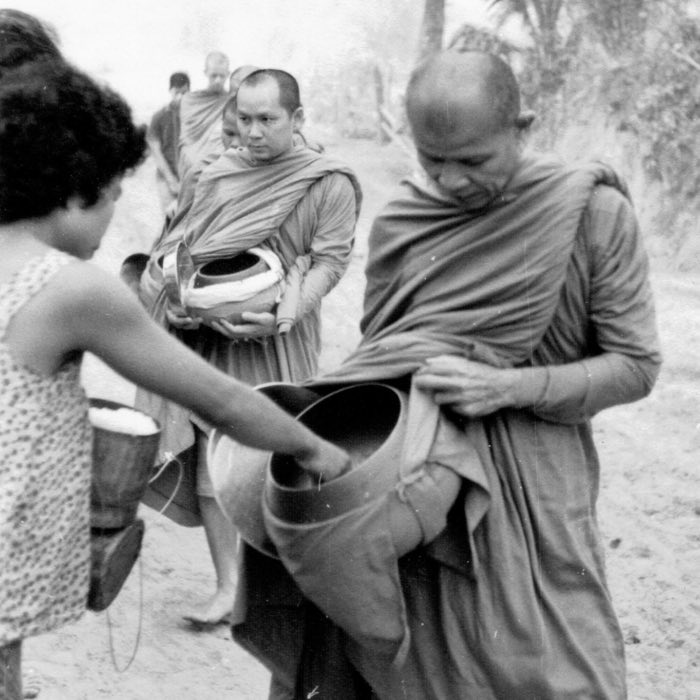

Samādhi: Meditative absorption

Samādhi refers to deep meditative concentration, an essential component of Buddhist practice that fosters mental clarity, tranquility, and insight. It represents the final aspect of the Noble Eightfold Path, encompassing Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration. Samādhi enables practitioners to stabilize the mind, overcome distractions, and cultivate the necessary conditions for insight and liberation (nirvāṇa).

In Buddhist thought, Samādhi is not merely about focusing attention but about unifying the mind, allowing it to rest in a state of undisturbed awareness. It supports wisdom (prajñā) by deepening insight into impermanence (anicca), suffering (dukkha), and no-self (anatta), reinforcing the path to liberation.

The Middle Way: Avoiding extremes

One of the defining principles of the Buddha’s teaching is the Middle Way (majjhimā paṭipadā), a path that steers clear of the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification. This principle emerged from Siddhartha Gautama’s own experience — after initially living in luxury as a prince and later embracing severe asceticism, he realized that neither extreme led to true liberation. Instead, he discovered a balanced approach that cultivated both wisdom and compassion, allowing for sustainable spiritual progress.

The Middle Way manifests in various aspects of Buddhist thought and practice:

- Philosophical balance: The Middle Way rejects rigid dogmatism as well as nihilistic skepticism. It encourages practitioners to develop a nuanced, experiential understanding of reality rather than clinging to fixed views.

- Ethical conduct: The Noble Eightfold Path itself is an expression of the Middle Way, providing a structured yet flexible approach to moral behavior, mental discipline, and insight.

- Meditative practice: In meditation, the Middle Way means balancing effort and relaxation — avoiding both agitation and passivity.

By following the Middle Way, practitioners cultivate moderation, wisdom, and inner harmony, avoiding the pitfalls of attachment to pleasure or aversion to hardship.

Tathatā: Buddhism’s view on reality as it is

Tathatā (Sanskrit; Pāli: tathatā or tathatāya) is a term often translated as “suchness” or “thusness”. It refers to the true nature of things as they are — beyond conceptual thought, beyond dualities, and beyond the categories of existence and non-existence. Tathatā expresses the idea that reality, in its most immediate and unfiltered form, simply is.

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, tathatā becomes a central concept for understanding the nature of ultimate reality (dharmadhātu). It is not something separate from everyday phenomena but is the very “thusness” of all phenomena, perceived without the distortion of craving, aversion, or delusion. In this sense, tathatā is both radically immanent and transcendent — it points to the absolute while being present in the relative.

Importantly, tathatā is not a metaphysical substance or hidden essence. It is the recognition that all things are empty (śūnya) of inherent existence and yet appear dependently arisen. When the mind is free from conceptual overlays, dualistic thinking, and egoic distortion, reality is seen in its suchness — vibrant, impermanent, and interconnected.

This insight into tathatā is closely related to meditative realization and non-conceptual awareness. It represents the goal of Buddhist wisdom (prajñā): not merely to understand doctrines, but to directly encounter the world without grasping or resistance — to see things “just as they are”. In Zen Buddhism, this is often summed up with the phrase: “Chop wood, carry water” — pointing to the sacredness of ordinary, unadorned experience when perceived without clinging.

Prajñā: Wisdom as liberating insight

Prajñā (Sanskrit; Pāli: paññā) is the Buddhist term for deep, liberating wisdom — the penetrating insight that sees things as they truly are. Unlike intellectual knowledge (vijñāna), which discerns and categorizes, prajñā transcends conceptual thought. It is the direct, experiential understanding of the impermanence (anicca), suffering (dukkha), and non-self (anatta) nature of all phenomena.

In the Buddhist path, prajñā plays a central and culminating role. It is the final component of the Threefold Training (triśikṣā): ethical conduct (śīla), meditative concentration (samādhi), and wisdom (prajñā). While ethics and meditation prepare the mind by purifying it and calming its fluctuations, prajñā is what cuts through ignorance (avidyā) — the root cause of suffering — and leads to awakening.

The cultivation of prajñā typically unfolds through:

- Study (śruta-mayī prajñā): Learning the Dharma from texts and teachers.

- Reflection (cintā-mayī prajñā): Contemplating and analyzing what one has learned.

- Meditation (bhāvanā-mayī prajñā): Realizing the truth directly through deep meditative insight.

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, prajñā is often linked with śūnyatā — the understanding that all things are empty of inherent, independent existence. This insight is not nihilistic but reveals the interdependent, fluid, and relational nature of reality. Such wisdom leads to compassion (karuṇā), because seeing the non-dual nature of self and other naturally fosters care for all beings.

Far from being abstract or esoteric, prajñā is intimately practical: it transforms how one relates to experience. It loosens the grip of craving and fear, softens fixed views, and opens the mind to reality without distortion. In this sense, prajñā is not just knowledge, but freedom — the clear seeing that liberates.

Conclusion

Buddhism’s conception of Dharma presents a radical shift from earlier Indian traditions, transforming it from a rigid cosmic order or set of social obligations into an experiential path rooted in wisdom, ethics, and meditation. Rather than an externally imposed duty or divine law, the Buddhist Dharma serves as an inner principle to be realized through direct experience. It is both the natural order that governs existence and the guiding framework for liberation from suffering.

This interpretation fundamentally reshaped the Indian religious landscape by prioritizing individual realization over ritualistic adherence. By rejecting the fixed hierarchies of caste-based Dharma and redefining it as a universal law accessible to all, Siddhartha Gautama provided a path that transcended social divisions and opened the possibility of awakening to anyone willing to cultivate insight and discipline. In this way, the Buddhist Dharma is profoundly egalitarian and pragmatic, directing focus toward what can be known, practiced, and actualized.

Yet, Dharma in Buddhism is not merely a philosophical abstraction; it remains deeply entwined with lived experience. It manifests in every moment, from the smallest ethical choices to the highest meditative attainments. The interwoven principles of impermanence, no-self, and dependent origination emphasize that reality is fluid and conditioned, and that liberation lies not in grasping at permanence but in embracing the changing nature of all things. The Dharma thus serves as a compass, guiding practitioners not toward external authority or metaphysical speculation, but toward direct, transformative insight into the nature of existence.

At its heart, the Buddhist Dharma is a call to self-transformation — a framework for cultivating wisdom, ethical clarity, and inner stability in a world of flux. It demands engagement, not passive belief. Those who walk the path of Dharma are not merely followers of a doctrine but participants in an ongoing process of realization, continually refining their understanding through practice and experience. In this sense, the Dharma is not just a set of teachings but an invitation: to see reality as it is, to abandon suffering at its root, and to embody the wisdom that leads to true freedom.

Iconic representation of the Dharma Wheel (dharmachakra). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

comments