The role of lay practitioners in Buddhism

While monastics have historically been the most visible custodians of Buddhism, the tradition has never been confined to monks and nuns alone. Lay practitioners—householders, workers, rulers, and ordinary citizens—have played a vital role in the transmission, adaptation, and lived expression of Buddhist teachings. Their relationship with the monastic sangha is symbiotic and dynamic, rooted in both doctrinal prescriptions and socio-cultural realities. In this post, we examine the historical, doctrinal, and practical roles of lay Buddhists, as well as how their position has evolved across different regions and schools of thought.

Doctrinal foundations: Lay life and the path

Early Buddhist texts, particularly those of the Pāli Canon, often frame the lay life as less conducive to full liberation compared to the renunciant path. Siddhartha Gautama himself emphasized the necessity of “going forth”—leaving behind household life—to cultivate the single-minded discipline required for enlightenment. However, this does not imply that laypeople are excluded from spiritual progress. On the contrary, lay ethics (such as adherence to the Five Precepts) and practices like generosity (dāna), merit-making, and meditation are frequently praised as essential components of the Dharma.

Numerous suttas recount stories of laypersons who attained various stages of awakening, such as stream-entry (sotāpanna) or once-returning (sakadāgāmi), which are the first two of four progressive stages on the path to full awakening as described in the early Pāli Canon and attributed to Siddhartha Gautama himself. A sotāpanna is one who has seen the truth of the DhammaDhamma and is guaranteed eventual liberation, no longer subject to rebirth in lower realms. A sakadāgāmi is one who will return to the human world at most once more before achieving further stages of enlightenment. These stages mark significant milestones in spiritual development and are attainable even by laypeople according to canonical texts, even while continuing to live in the world. Figures like Anāthapiṇḍika, the wealthy merchant and foremost male lay supporter of the Buddha, is said in the Anāthapiṇḍikovāda Sutta (MN 143) to have received a profound discourse on non-attachment on his deathbed, indicative of his deep spiritual maturity. Visākhā, similarly, is portrayed as an exemplary laywoman in texts such as the Dakkhiṇāvibhaṅga Sutta (MN 142), noted for both her generosity and wisdom.

Another notable case is the householder Citta, described in the Citta Saṃyutta (SN 41), who was praised by the Buddha for his profound understanding of the Dhamma and for engaging in deep doctrinal discussions even with senior monks. These individuals, though not ordained, were seen as having grasped the essence of the teachings, providing canonical affirmation that spiritual depth is not the exclusive domain of the monastic order.

Their presence in the canon legitimizes the possibility of awakening and serious practice within lay life, offering models of devotion, insight, and spiritual attainment that transcend institutional boundaries.

Support and reciprocity: Laypeople and the sangha

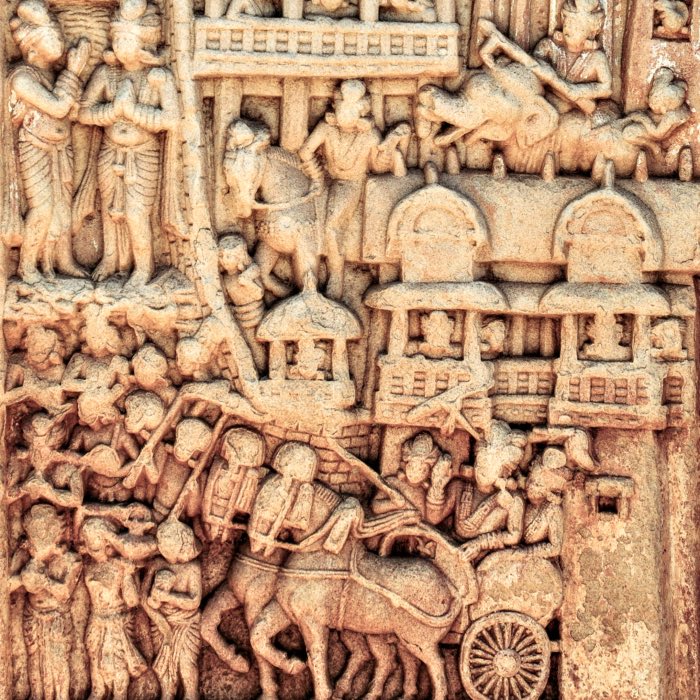

The relationship between lay followers and the monastic sangha has historically been based on a reciprocal exchange. Lay practitioners provide material support—alms, clothing, medicine, shelter—which enables monastics to dedicate themselves to study and meditation. In turn, monastics serve as teachers, ritual specialists, and moral exemplars. This relationship is framed not as one of dependence, but as mutual benefit: monastics act as a “field of merit” for laypeople, while lay support upholds the continuity of the Dharma.

This symbiosis is not only economic but spiritual. By supporting the sangha, laypeople participate in the perpetuation of the Buddhist path, accumulating merit and cultivating the virtues of generosity, humility, and interconnectedness. The act of giving is a practice in itself, often imbued with deep intentionality and karmic aspiration.

Practice in daily life: Ethical living and meditation

For lay Buddhists, practice often means integrating the Dharma into the complexities of daily life. While full-time renunciation may be out of reach, laypeople are encouraged to live ethically, reflectively, and mindfully. The Five Precepts form the baseline of ethical conduct, while more committed lay followers may adopt additional observances on Uposatha (observance) days.

Meditation, though historically emphasized in monastic settings, has increasingly become part of lay life, particularly in modern Theravāda and Zen contexts. In recent decades, meditation centers, lay-led retreats, and popular Buddhist literature have made contemplative practice accessible to a broad audience. This democratization of practice reflects both doctrinal flexibility and the evolving social landscape of global Buddhism.

The lay path in Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, the role of the layperson receives even greater emphasis. The bodhisattva ideal, which encourages practitioners to remain in the world to assist others, collapses the binary between lay and monastic life. Lay figures such as Vimalakīrti, a householder portrayed as spiritually superior to monks in the Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa Sūtra, are held up as embodiments of wisdom and skillful means. In this influential Mahāyāna text, Vimalakīrti feigns illness to attract visits from prominent monks and bodhisattvas, whom he then engages in deep philosophical dialogues—often outshining them in insight and rhetorical brilliance. One of the most well-known episodes is his “thundering silence” when asked to explain the nature of nonduality, a gesture that is interpreted as the highest teaching. These narratives underscore the Mahāyāna view that deep insight and liberation are not the exclusive domain of the ordained, but equally available to those who engage with the world compassionately and wisely.

In Vajrayāna contexts, especially in Tibetan Buddhism, advanced tantric practices are not necessarily confined to monastics. While proper initiation and guidance are critical, lay practitioners may engage in profound ritual and meditative techniques aimed at enlightenment in a single lifetime. Figures such as Marpa the Translator, who remained a layperson throughout his life, exemplify the possibility of attaining high realization outside the monastic framework. His story, along with that of his disciple Milarepa, reflects the Vajrayāna emphasis on devotion, direct experience, and the transformative power of esoteric methods.

Thus, in both Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna, the lay path is not merely preparatory or auxiliary, but potentially complete in itself—a full vehicle for awakening shaped by the values of compassion, wisdom, and committed practice.

Contemporary developments

Modernity has further blurred the lines between monastic and lay roles. In urban centers and diasporic communities, lay teachers, scholars, and practitioners have assumed leadership in transmitting the Dharma. Western and globalized forms of Buddhism have adapted to lifestyles where full renunciation is rare, emphasizing instead a lay path that balances spiritual depth with everyday responsibilities. Increasingly, laypeople take on roles previously reserved for monks, including teaching meditation, leading study groups, and offering pastoral care, particularly in communities with limited monastic presence.

Digital platforms, social media, and online sanghas have created new modes of lay engagement, allowing for study, discussion, and collective practice across geographic boundaries. Podcasts, YouTube channels, and online courses hosted by both lay and monastic teachers have contributed to a transnational lay awakening. These resources offer flexible formats that appeal to laypeople navigating modern life, while still fostering disciplined engagement with the Dharma. At the same time, lay practitioners continue to support traditional monastic institutions—through donations, volunteer work, and participation in rituals—ensuring continuity while expanding access.

Conclusion

Lay practitioners have always been more than peripheral participants in Buddhism. They are essential to its vitality, transmission, and ongoing relevance. From the earliest canonical texts through the flourishing of Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions to the global forms of modern Buddhism, laypeople have demonstrated that deep spiritual practice is not the exclusive domain of monastics. Their roles as ethical exemplars, patrons, teachers, and cultural transmitters have helped shape Buddhism into a diverse and resilient tradition.

Buddhism offers a unique framework in which lay life is not merely tolerated but meaningfully integrated into the path toward awakening. Unlike many Western religious frameworks that emphasize hierarchical or doctrinal mediation through clergy, Buddhism often emphasizes experiential understanding and ethical living accessible to all. The lay path, while challenging due to worldly entanglements, is also a test bed for applying Buddhist principles in real-world contexts—relationships, work, parenting, and civic life.

This integration makes Buddhism particularly adaptable to modern secular and pluralistic societies. While Western religious traditions may struggle with the tension between spiritual authority and lay autonomy, Buddhism—particularly in its Mahāyāna and contemporary global forms—often collapses that dichotomy. In doing so, it not only broadens access to spiritual development but also affirms the value of ordinary life as a valid and fertile ground for awakening.

The challenge moving forward will be to maintain the integrity and depth of the tradition as lay roles expand. But the historical precedent is clear: lay practitioners have long been instrumental to Buddhism’s adaptability and strength. As Buddhism continues to evolve in diverse cultural settings, the lay path will likely remain not only relevant but central to its future.

References and further readings

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

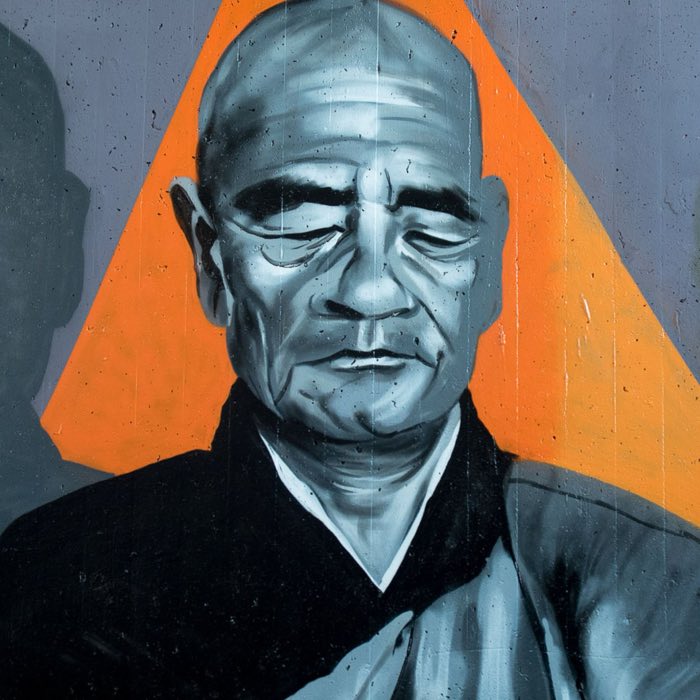

- Norman Waddell (Herausgeber), Bankei Eitaku, Die Zen-Lehre vom Ungeborenen. Leben und Lehre des großen japanischen Zen-Meisters Bankei Eitaku (1622 - 1693), 1988, ISBN-10: 3502640505

comments