Interpenetration and the mirror of reality — From Dependent Origination to Huayan thought

Emptiness (śūnyatā) lies at the heart of Mahāyāna philosophy. Nāgārjuna’s great insight — that all dharmas are empty because they arise dependently — served as a profound antidote to metaphysical essentialism. But emptiness is not an end in itself. It points beyond fixed views not to nihilism, but to a deeper vision of relational reality. What happens when we follow this insight all the way through? In this post, we explore that question by tracing the evolution from Nāgārjuna’s analytic clarity to the luminous vision of interpenetration developed in the Huayan school. From negation of self-nature to affirmation of mutual presence — we follow the path from emptiness to its flowering as totality.

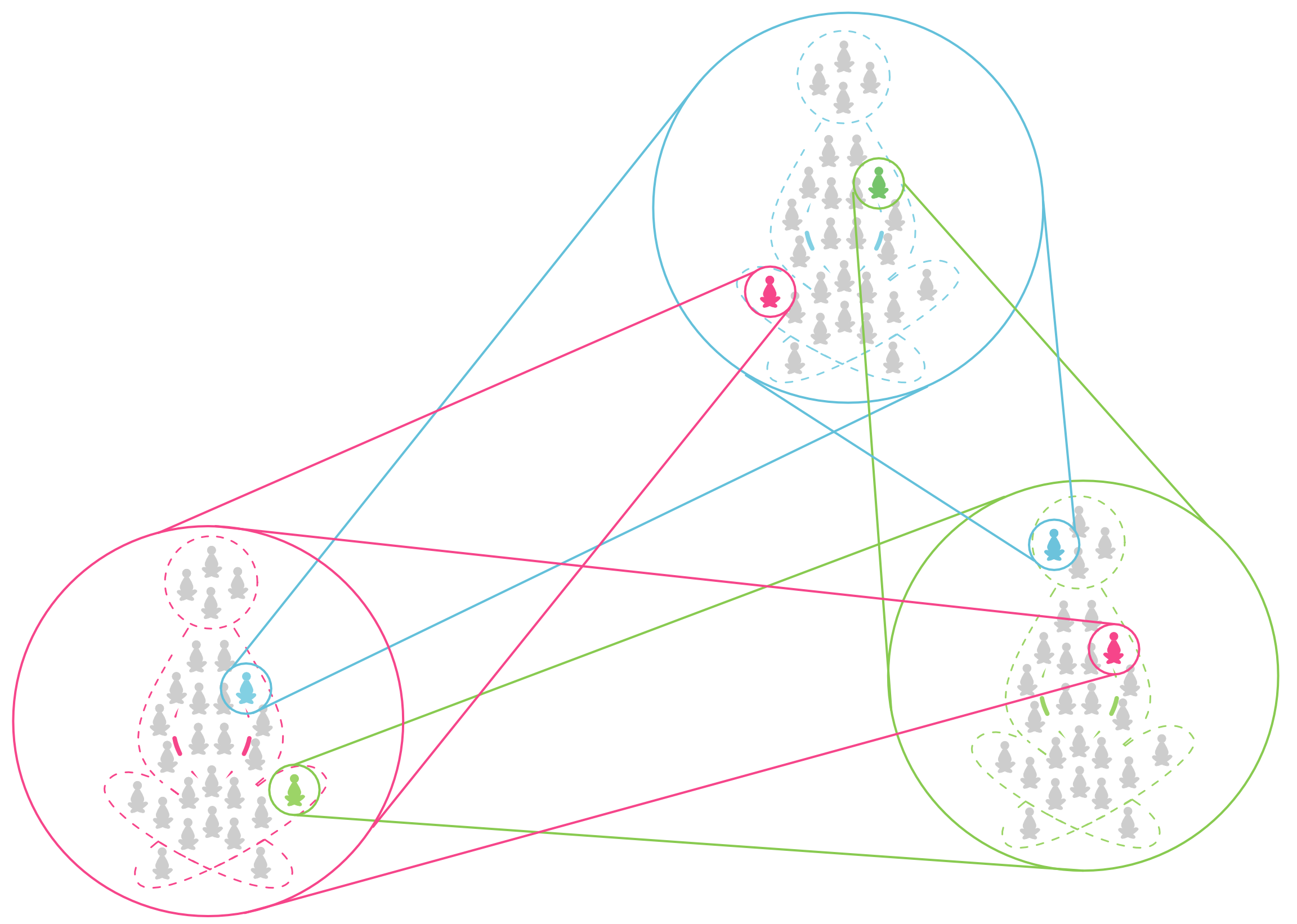

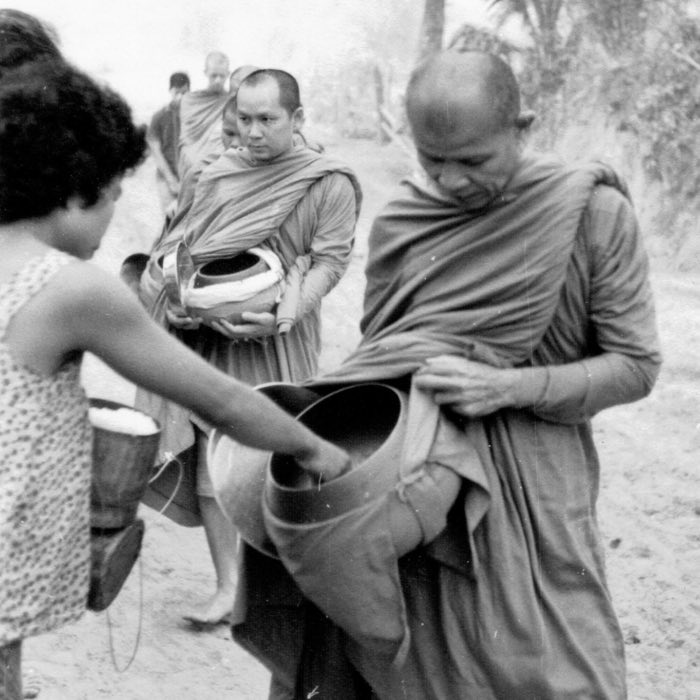

Artistic representation of Indra’s Net, a central metaphor in Huayan Buddhism. Each jewel reflects all others, illustrating the principle of total interpenetration: everything reflects and contains everything else, endlessly and without obstruction. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Going beyond Nāgārjuna: Toward a fuller vision of emptiness

Nāgārjuna’s profound contribution to Buddhist thought lies in his clarification of emptiness (śūnyatā) as the absence of intrinsic nature (svabhāva) — in alignment with the anattā (non-self) doctrine, and in his equation of this emptiness with dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda). Through his dialectical method, he dismantled all fixed views, leaving behind a radically open vision of reality: all things are empty because they arise only in dependence on other things. This insight served as a powerful critique of essentialism and safeguarded the Dharma from reification.

Yet Mahāyāna thought did not end with Nāgārjuna’s negations. Later traditions, especially the Avataṃsaka or Huayan school in China, built upon this foundation and moved beyond deconstructive analysis toward a more integrative vision of reality. While Nāgārjuna emphasized the emptiness of all dharmas, Huayan thinkers asked what it means for all dharmas to be equally empty — and arrived at the idea that they are therefore not just co-arising, but mutually containing.

This shift gave rise to the doctrine of interpenetration: the insight that each phenomenon reflects, includes, and depends on all others. Rather than merely negating essence, this vision celebrates the infinite connectivity of the world. From “each dharma lacks essence” we move to “each dharma contains all dharmas”. What emerges is not an abstract metaphysics, but a deep affirmation of relational being — a world seen not as a collection of isolated things, but as a seamless web of mutual reflection.

From emptiness to interdependence to interpenetration

Nāgārjuna’s great insight was that to be empty is to be dependent — that nothing exists by its own nature, but only as a result of causes and conditions. This is the heart of pratītyasamutpāda — dependent origination — and it is precisely this principle that underlies the concept of śūnyatā. What appears as negation or absence is in fact a relational vision of reality. A dharma is not a thing with its own substance, but a node in a web — brought forth by its conditions and gone when they dissolve.

Yet if no dharma exists in isolation, then each dharma exists through all others. This leads to a shift in emphasis: from the absence of self-nature to the fullness of mutual constitution. If everything is dependently arisen, then everything bears the trace of everything else. From Nāgārjuna’s analytic dismantling of essence arises a new kind of vision — one that sees each phenomenon not just as empty, but as saturated with the presence of the whole.

The Huayan school of Buddhism made this shift explicit. Emerging in 7th-century China, Huayan (華嚴, “Flower Garland”) was based on the Avataṃsaka Sūtra and flourished during the Tang dynasty. Its central doctrine was that of the mutual interpenetration of all phenomena (dharmas) and their non-obstruction (wu’ai 無礙). Building on the logic of dependent origination, Huayan thinkers articulated a universe in which each phenomenon contains all others — not metaphorically, but ontologically. A key formulation that expresses this view is: “Each dharma is composed of non-dharmas” — each dharma is composed entirely of what it is not. Its identity is not in itself, but in the entire field of relations that make it what it is. This is not a departure from emptiness, but its fullest unfolding.

Thus, interdependence deepens into interpenetration: a vision in which every aspect of reality is mirrored in every other, and nothing can be isolated without distorting the whole.

The metaphor of the chariot revisited

One of the most well-known metaphors in classical Buddhist thought is the chariot dialogue from the Milindapañha, which we have already encountered in our exploration of the anatta doctrine and in which the Greek king Milinda questions the monk Nāgasena. When asked what a chariot is, Nāgasena demonstrates that the term “chariot” refers not to a singular entity but to a configuration of parts: wheels, axle, yoke, and so on. None of these parts alone is the chariot, and the chariot cannot be found apart from them. This becomes a tool to explain the nature of the self: it too is not a unitary essence, but merely a designation for a collection of physical and mental components in flux.

Illustration of a chariot, referencing the famous simile from the Milindapañha. According to the Buddhist monk Nāgasena, just as a chariot is merely the sum of its parts — wheels, axle, yoke — and not a substance of its own, so too is the self a conventional designation for the five aggregates (skandhas). No enduring essence can be found in either. Interpreted and generated by DALL•E.

This insight, however, can be extended beyond the self to include all dharmas. Any phenomenon, when closely examined, reveals itself to be a temporary configuration — composed not of some inner essence, but of other phenomena that are themselves empty and dependent. In this light, all dharmas are like chariots: nothing in themselves, yet functioning conventionally by virtue of their relations.

This leads to a powerful realization: not only are all things empty, but they exist through one another. A dharma does not simply lack essence — it is composed of everything that it is not. Each thing is what it is only because of the countless other things that make it so. Thus, we move from the chariot as a metaphor for non-self to the chariot as a symbol for total inter-containment. No dharma exists alone; to perceive anything clearly is to perceive the entire web that allows it to be.

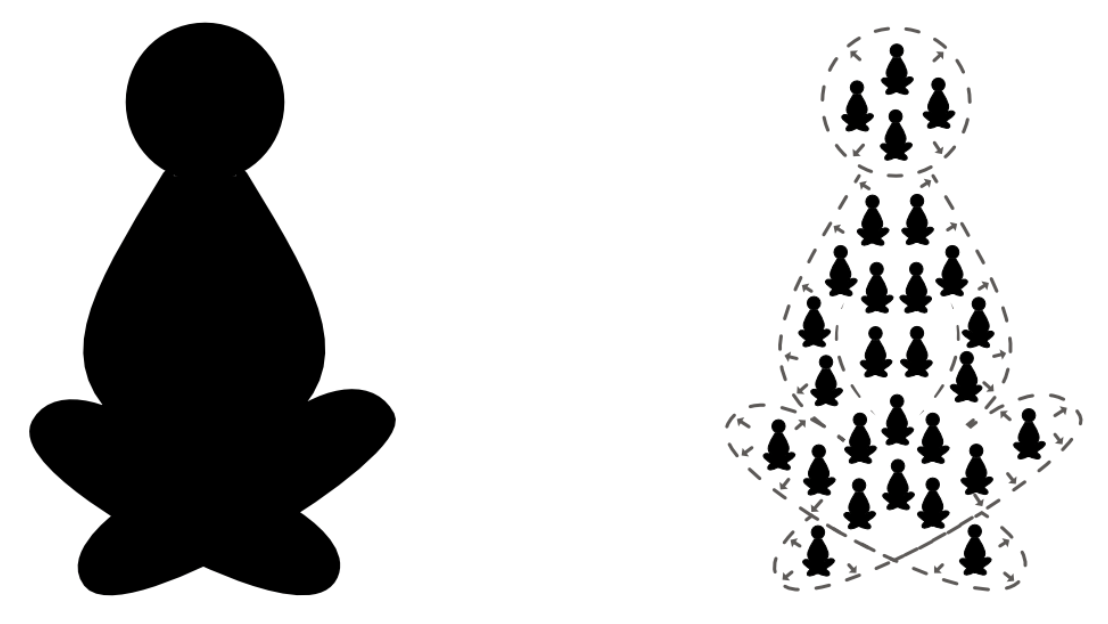

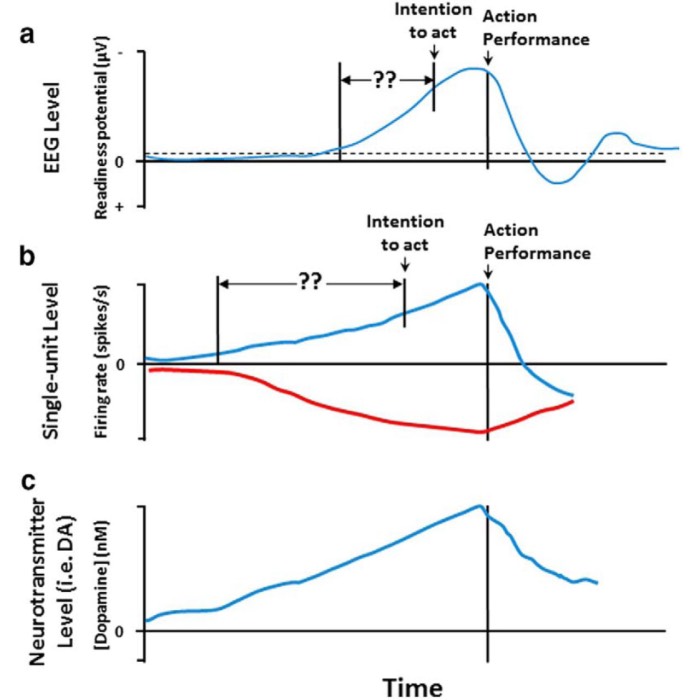

Visualizing the deepening of emptiness

The classical chariot metaphor teaches that a thing is not found within itself, but in the configuration of its parts. We now attempt to visualize this idea as clearly as possible. The first image is sought to illustrate the concept of emptiness as the absence of intrinsic essence:

A dharma analyzed into its constituent parts. Each component is distinct, and the whole has no existence apart from them.

A single dharma, when examined, dissolves into a multiplicity of other dharmas. Its apparent unity is merely conventional — a result of relational assembly. There is no hidden core, no essence; only a pattern emerging from dependencies.

Pushing this insight further, we arrive at a startling formulation: each dharma is composed of non-dharmas. That is, what something is depends entirely on what it is not. This second image visualizes that truth:

Each dharma is composed of all other dharmas — but never includes itself. The constitution of one is the field of others

Every dharma reflects all others, and its identity arises from its absence in the midst of presence. It contains the whole field — except itself. This is not a logical paradox, but the structure of reality as seen through the lens of dependent origination.

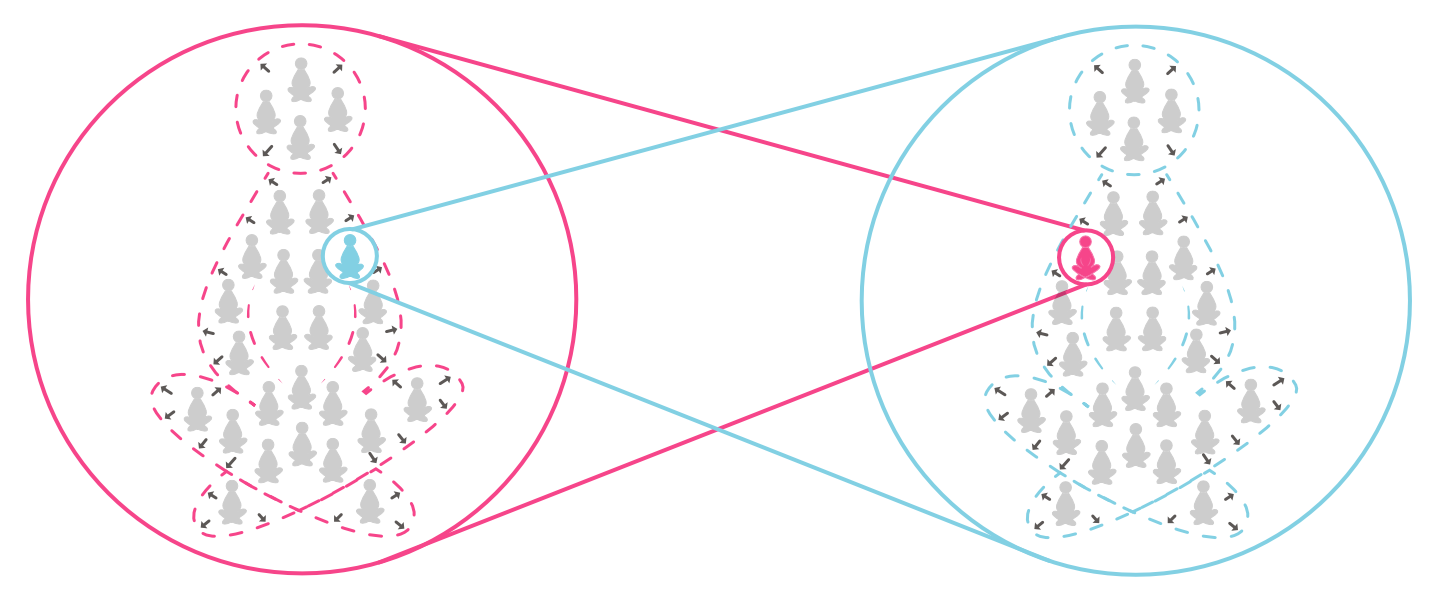

When this principle is applied universally, it gives rise to a vision of mutual reflection and containment. The third image captures the structure of interpenetration:

A web of interdependent dharmas, each composed of all others. This network structure forms the basis of interpenetration.

Each dharma is composed of all others, and each of those in turn composed likewise. The result is a self-sustaining net of dependencies — luminous and recursive. This is the very structure illustrated by Indra’s Net (see below) and elaborated in Huayan metaphysics. Here, the logic of emptiness becomes a logic of total reflection.

Indra’s Net and the logic of total reflection

A central metaphor in Huayan Buddhism is that of Indra’s Net, drawn from the Avataṃsaka Sūtra. This image describes an infinite cosmic web, with a luminous jewel placed at each intersection. Each jewel reflects all the others — and each of those reflections in turn contains reflections of every other jewel. This recursive, boundless reflection illustrates the principle of total interpenetration: everything reflects and contains everything else, endlessly and without obstruction.

“Imagine a multidimensional spider’s web in the early morning covered with dew drops. And every dew drop contains the reflection of all the other dew drops. And, in each reflected dew drop, the reflections of all the other dew drops in that reflection. And so ad infinitum. That is the Buddhist conception of the universe in an image.” –Alan Watts. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The significance of this image lies in its philosophical clarity. It shows that no dharma can be isolated or fully understood apart from the whole. The nature of any one thing is always already infused with the presence of all things. There is no hierarchy, no center, no ultimate foundation — just a field of mutual presence. To see one jewel clearly is, in principle, to glimpse the entire net.

This is not mystical fusion or metaphysical oneness, but radical relationality. Each thing remains distinct, yet it expresses all others. In Huayan thought, this non-obstruction between the one and the many, between appearance and principle, is called li shi wu’ai (理事無礙): the non-obstruction of principle and phenomena. Reality is neither fragmented nor collapsed into unity — it is a dynamic, luminous interweaving in which everything is fully itself only because it participates in everything else.

Fazang’s Golden Lion and the Ten Profound Gates

A defining figure of the Huayan school, Fazang (643–712), offered one of its most compelling illustrations of interpenetration through his essay on the golden lion. Written as an explanation for Empress Wu, this treatise uses the image of a lion statue made of gold to illuminate the nature of reality.

The statue’s form — ears, mane, eyes, claws — represents the diversity of phenomena, while the gold represents the underlying nature that pervades them all. The key insight is this: the gold is present equally in every part, and each part reflects the entirety of the lion. Thus, every component — no matter how small — contains and expresses the whole. This is the doctrine of mutual containment (xiangji 相即) and interpenetration (xiangru 相入).

Building on this, Fazang developed the “Ten Profound Gates” — a set of principles to express the complete interrelationship of all things:

- Simultaneous arising of phenomena and principle — Like gold and lion appearing together: the form (lion) and the substance (gold) are mutually dependent and co-arise.

- Mutual non-obstruction of essence and form — The gold and the lion do not hinder each other: form and emptiness coexist without conflict. Each part retains its position even when viewed through emptiness.

- Mutual interpenetration of all phenomena — The lion’s eye contains the whole lion; thus, each part is the whole, and the whole is in each part.

- Individual distinctiveness without obstruction — Every element of the lion (eyes, ears, hairs) is both itself and all others; they interpenetrate but remain unimpeded and distinct.

- Concealment and revelation of essence and manifestation — When we see the lion, the gold is hidden; when we see the gold, the lion vanishes. The seen hides the unseen.

- Complete compatibility between emptiness and form — Both the gold and the lion can be hidden or revealed, yet emptiness (principle) and form (phenomena) shine together in harmony.

- Infinite reflection of phenomena within each other — Each part of the lion reflects all others: infinite lions appear in every hair, just as in Indra’s Net.

- Dual function of words to point beyond concepts — ‘Lion’ shows the illusion born of ignorance; ‘gold’ points to true nature. Words indicate both delusion and insight.

- Interdependence of temporal sequences — The lion arises and perishes in every moment, but all moments interdependently generate each other and flow freely.

- Mental transformation as ground of appearance — Neither lion nor gold has independent nature; their appearance depends on the transformations of mind.

Through these gates, Fazang presents a cosmos in which every moment, form, and relation expresses the entirety of the dharma realm. “Everything contains everything without confusion” — this is not a poetic metaphor, but a precise articulation of a reality structured by interpenetration. Each hair of the lion is the lion; each point in space and time reveals the whole.

A famous verse from the Avataṃsaka Sūtra puts it this way:

In every mote of dust are countless worlds and Buddhas. From each tip of a single hair of the Buddha’s body are revealed the indescribable, pure lands. All infinite realms are gathered in the tip of one hair.

This poetic imagery captures the very heart of Huayan’s vision: that the cosmos is infinitely mirrored within each part, and that the smallest point of being contains the totality of reality. This is the Huayan vision of a universe without boundaries, where the absolute and the relative, the one and the many, exist in perfect mutual inclusion.

Interpenetration as Suchness

In the Huayan tradition, tathatā — suchness — is not conceived as a hidden essence behind phenomena,

but as their true nature precisely as they are: interdependent, empty, and mutually reflecting. Suchness is not something added to reality, nor is it a metaphysical substratum. It is the direct, non-conceptual recognition that all things arise within a vast, relational matrix in which nothing stands alone. To see a thing’s suchness is to see its contingency, its impermanence, and its participation in the whole.

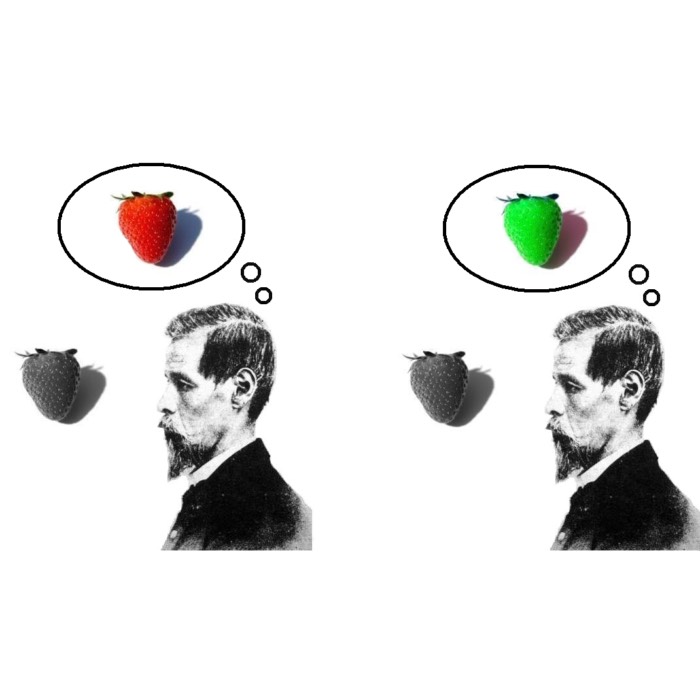

This recognition is not of something hidden behind appearance, but of what is present within appearance when seen rightly. While the analysis of dependent origination and emptiness begins as a conceptual insight, its transformative power lies in direct experience. It is only through living and seeing suchness that one moves beyond intellectual understanding to liberating wisdom — prajñā-pāramitā. Tathatā is thus not the “beyond” of reality, but its unadorned immediacy — plain, unobtrusive, yet infinitely deep. It is what becomes apparent when the mind no longer overlays its projections onto the world. In this sense, śūnyatā and tathatā are not two insights but a single vision: emptiness is suchness, suchness is emptiness.

To see things as they are is to see that no dharma exists by itself — that each one, in its very contingency, reflects the whole. This vision collapses the dualities of subject and object, self and other, and absolute and relative — not by erasing difference, but by showing their interdependence. In this way, interpenetration is not merely a philosophical claim, but the lived, experiential realization of śūnyatā. It is tathatā made visible — the suchness of all things as they arise together, reflect one another, and express the Dharma in their very contingency.

And because dharmas are empty, they are not less real, but more intimately knowable — constantly arising and ceasing in the web of conditions, yet never isolatable. The ordinary concept of existence, as something fixed or self-subsisting, does not apply here. Instead, existence means participation, reflection, responsiveness. Suchness, then, is the world itself — seen without grasping, without projection, and without separating the seer from the seen. From this view, it becomes clear: I exist only because of all other dharmas — those that came before, those yet to arise, and those co-arising now. Nothing stands apart, and nothing is dispensable. It is the quiet radiance of what is always already here, when seen without delusion — a world not hidden, but patiently present.

When we see the lion, and truly recognize that every dharma arises through conditions and is originally calm and empty, wisdom (prajñā) begins to unfold. Whether the mind meets beauty or ugliness, gain or loss, it rests undisturbed like a clear sea. Freed from grasping and aversion, one enters the path toward nirvāṇa — not by escape, but by seeing things as they are, and no longer generating suffering from illusion.

Ethical and meditative implications

The Huayan vision of interpenetration has profound ethical and meditative consequences. If all beings arise in mutual dependence and reflect one another without obstruction, then compassion becomes more than an ideal — it is a recognition of the fabric of reality. Harming another is, in effect, harming oneself, because the boundaries that seem to separate us are conventionally real but ultimately empty. This insight calls not only for empathy, but for a radical responsibility: one’s life is not isolated, but a confluence of innumerable conditions, relations, and contributions by others.

In practice, this understanding transforms meditation. Rather than striving to escape the world, the practitioner learns to rest within it — no longer grasping at or rejecting phenomena, but seeing each dharma as a mirror of the whole. Stillness arises not by suppression, but by letting go of the illusion of fixed, separate things. When the mind no longer clings to identities or conceptual distinctions, it becomes transparent to the web of being.

Awakening in this tradition is not withdrawal into a private realization, but the unfolding of wisdom and compassion within the world. To awaken is to see the net, to become transparent to it, and to live in accord with its luminous, interdependent design.

Reception and legacy of Huayan interpenetration

The Huayan vision of interpenetration stands as one of the most intricate and luminous developments within Mahāyāna Buddhism. Yet its reception has varied across traditions, cultures, and time periods.

Within East Asia, Huayan had a profound impact, especially on Chán (Zen) Buddhism, which absorbed many of its insights into its own language of immediacy, suchness, and nonduality. The emphasis on direct experience and the inherent unity of all things found a ready echo in Zen’s refusal to separate the sacred from the everyday. In Korea, the Hwaeom school (Huayan’s counterpart) became one of the foundational strands of Seon (Korean Zen). In Japan, Kegon Buddhism carried its legacy forward, influencing later developments in Tendai and Shingon thought.

However, Huayan’s intricate metaphysics also drew critique and resistance. Some schools viewed its highly elaborate ontological vision as a return to subtle forms of essentialism or reification — despite its avowed grounding in emptiness. Others, particularly in the Madhyamaka tradition, preferred to maintain Nāgārjuna’s radical apophatic stance, wary of any system that seemed to posit a positive metaphysics of the dharma realm.

In modern scholarship, Huayan’s doctrine of interpenetration has sparked comparisons with Western systems of thought — from Leibniz’s monads (indivisible, self-contained units mirroring the universe) and Hegel’s dialectics (a process of unfolding truth through the resolution of contradictions) to systems theory (the study of complex wholes formed by interrelated parts), ecology (the study of interrelationships between organisms and their environments), and even quantum entanglement (the physical phenomenon in which particles remain connected so that the state of one affects the other, no matter the distance). While such comparisons are often speculative, they reflect a deep resonance: the vision of a world in which each part reflects and depends on the whole.

Today, Huayan’s insights continue to inspire ecological, ethical, and philosophical thought — offering a model of interconnectedness that moves beyond individualism and dualism. Whether embraced or critiqued, the doctrine of interpenetration remains one of the boldest and most beautiful expressions of what it means to see the world not as it appears to the fragmented mind, but as it truly is: luminous, interdependent, and complete.

Conclusion

Nāgārjuna dismantled all illusions of self-existence, revealing a world devoid of inherent essence — empty because conditioned. This radical insight laid the foundation for a profound reimagining of reality in the Huayan tradition. Building upon this analytic clarity, Huayan thinkers reoriented emptiness from mere absence to luminous interdependence. Emptiness was no longer a negation of being, but the space within which all beings reflect and contain each other.

The arc from dependent origination to interpenetration reveals a movement from seeing things as contingent to seeing them as mutually constitutive. Fazang’s golden lion and the image of Indra’s Net gave voice to a world in which every part reveals the whole, and nothing stands alone. Huayan reframes reality not as a collection of independent substances, but as a field of endlessly mirrored relations — where each dharma contains all others without obstruction.

In contrast to some Buddhist schools that emphasized personal liberation through detachment or transcendence, Huayan’s vision is world-affirming. It does not oppose form to emptiness, or nirvāṇa to saṃsāra, but sees them as interwoven. It shares much with Zen in this regard, and yet it articulates the relational structure with unparalleled philosophical subtlety. Where Madhyamaka cautions against reification, Huayan explores what emerges when non-reification becomes a vision of luminous totality.

Critically, Huayan’s vision risks being misunderstood as metaphysical holism or spiritual monism. Yet it remains grounded in śūnyatā: the absence of essence is what allows for total presence. This makes it different from most Western ontologies, which often posit either atomistic individuals or substance-based unities. Nevertheless, parallels exist: in Leibniz’s monads, Hegelian totality, ecological systems, or quantum relationality — each of which grasps, in its own terms, the intuition that nothing is fully itself without all else.

What sets Huayan interpenetration apart is not just its philosophical elegance, but its experiential and ethical implications. To awaken is not to escape the world, but to see it rightly — as a net of mutual arising, where compassion is no longer optional, but a recognition of fact. In this light, Huayan is not just a doctrine, but a path: from emptiness, to relation, to the flowering of wisdom in the heart of everyday existence.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Bernhard Weber-Brosamer, Dieter M Back, Die Philosophie der Leere: Nagarjunas Mula-Madhyamaka-Karikas, 2006, Harrassowitz, O, ISBN-10: 9783447052504

- Lutz Geldsetzer, Nagarjuna, Die Lehre von der Mitte - (Mula-madhyamaka-karika) Zhong Lu, 2010, Meiner, F, ISBN: 9783787321377

- Nāgārjuna, David J. Kalupahana, Mūlamadhyamakakārikā of Nāgārjuna, 1991, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN: 9788120807747

- Christopher I. Beckwith, Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia, 2015, Princeton University Press, ISBN 10: 0691166447

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

comments