Dharmapālas: Guardians of the Buddhist path

Dharmapālas, or “Guardians of the Dharma”, are among the most striking figures in Buddhist tradition. With their fierce and wrathful appearances, they embody the paradox of compassionate protection through intensity. These protectors serve a dual purpose: safeguarding the teachings of the Buddha from external and internal threats while symbolizing the inner strength and clarity required to overcome obstacles on the path to awakening. In this post, we explore their origins, roles, and relevance across Buddhist traditions.

Left: Statue of Kundali (軍荼利明王; Juntuli Mingwang) one out of two Wisdom Kings, or vidyaraja (明王; Mingwang), in Fusheng Temple (福勝寺), Yuncheng, Shanxi, China, Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368). Kundali is a wrathful manifestation of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (觀世音菩薩; Guānsìyīn Púsà) and is often depicted with a snake coiled around his body. He is associated with the protection of Buddhist teachings and the dispelling of obstacles. Kundali is also known for his ability to transform negative energies into positive ones, symbolizing the transformative power of compassion and wisdom. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0). – Right: Wooden statue of Fudō Myōō (不動明王; Acalanātha), a wrathful deity in Japanese Buddhism, representing the fierce aspect of wisdom and the power to cut through ignorance. He is often depicted holding a sword and surrounded by flames, symbolizing his role as a protector of the Dharma. Fudō Myōō is associated with the purification of negative karma and the dispelling of obstacles on the path to enlightenment. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Introduction

Among the many figures in the Buddhist pantheon, Dharmapālas, literally “protectors of the Dharma”, stand out for their fierce iconography and their role as guardians of the Buddhist path. They challenge modern assumptions about Buddhism as a purely pacifist tradition by embodying a wrathful yet compassionate energy directed toward the defense of ethical practice and spiritual integrity. Though they may appear terrifying, Dharmapālas are understood not as violent aggressors but as fierce expressions of awakened compassion, acting on behalf of truth and clarity against delusion and harm.

The significance of Dharmapālas lies in their dual role: they operate both as protectors of the teachings and as embodiments of the inner resolve needed to maintain the path in the face of obstacles, whether internal afflictions like anger and ignorance or external threats to monastic institutions and practitioners. This dual role has made them central to tantric ritual, monastic discipline, and lay devotional practice, especially in Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna contexts.

Historically, some Dharmapālas originated as local deities or spirits who were subjugated or converted by great teachers such as Padmasambhava and bound by oath to serve the Dharma. Others are wrathful emanations of Buddhas or Bodhisattvas, appearing in terrifying forms to subdue powerful forms of egoic resistance. Over time, these figures became highly symbolic representations of the fierce clarity and ethical vigilance needed to protect insight from corruption. Whether as mythic beings, psychological metaphors, or ritual focal points, Dharmapālas play a vital role in sustaining and transmitting the path of awakening.

Origins and functions

The term “Dharmapāla” is a compound of two Sanskrit words: dharma, meaning truth, law, or the Buddha’s teaching, and pāla, meaning protector or guardian. Together, they denote a class of beings whose primary role is to safeguard the Buddhist path. While the concept of divine or supernatural protection is not unique to Buddhism, the Dharmapāla occupies a particular place within the tradition, acting not from personal allegiance or favor but from a vow-bound commitment to the integrity of the Dharma itself.

The appearance of Dharmapālas as clearly defined figures is more pronounced in Mahāyāna and especially Vajrayāna Buddhism. While early canonical sources make reference to guardian deities or spirits who protect practitioners, it is within later sūtras and tantric texts that Dharmapālas emerge as ritualized, iconographically detailed, and doctrinally integrated entities. These figures became especially important in regions like Tibet, where Buddhism encountered complex local religious landscapes and where the need to symbolically assert the dominance and sanctity of the Dharma became part of its institutional consolidation.

Dharmapālas generally perform three interrelated functions. First, they protect practitioners and the teachings themselves. This includes safeguarding monasteries, teachers, texts, and ritual spaces from both worldly and spiritual threats. Second, they are invoked to subdue obstacles — not only external forces such as malevolent spirits or enemies of the faith, but also internal hindrances like fear, anger, or delusion. In this sense, they serve both exoteric and esoteric roles. Third, Dharmapālas embody a paradox at the heart of Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna ethics: that wrath can be a form of compassion. Their terrifying appearances, weapons, and flames are not signs of hatred but expressions of fierce benevolence — wrathful means deployed to destroy the roots of suffering.

These functions reflect the dual register on which Dharmapālas operate: as protectors of the institutional Dharma and as catalysts for the practitioner’s inner transformation. Their emergence reflects both the practical challenges faced by Buddhist communities in history and the deeper philosophical recognition that compassion does not always appear in gentle form.

Types of Dharmapālas

The category of Dharmapālas encompasses a wide range of figures with diverse origins, statuses, and modes of operation. To better understand their roles, Buddhist traditions have developed several overlapping classifications, distinguishing them based on their metaphysical status, doctrinal origin, and relationship to the Dharma they protect.

Worldly vs. supramundane protectors

One of the key distinctions is between “worldly” (lokapāla) and “supramundane” (lokottara) Dharmapālas. Worldly protectors are beings who still exist within the cycle of birth and death (saṃsāra) and may not have fully overcome delusion or karmic conditioning. While bound by oath or ritual commitment to serve the Dharma, their motivations may be shaped by loyalty, reverence, or fear rather than full awakening. Examples include regional deities or nature spirits who have been ritually converted to Buddhist service. Supramundane protectors, by contrast, are manifestations of fully enlightened beings — Buddhas or advanced Bodhisattvas — who appear in wrathful forms not out of defilement, but as skillful means (upāya) to benefit beings.

Wisdom deities vs. oath-bound spirits

A related distinction exists between transcendent wisdom deities and oath-bound spirits. The former category includes Dharmapālas who are direct emanations of awakened awareness, such as Yamāntaka, a wrathful form of Mañjuśrī, who embody specific aspects of enlightened mind. These figures are integrated into tantric mandalas and ritual practices as aspects of the practitioner’s own realized potential. Oath-bound spirits, by contrast, are often non-enlightened beings who have been subdued or converted through ritual means, typically by tantric masters like Padmasambhava, and bound by sacred vow (samaya) to protect the Dharma. Though powerful and effective, their allegiance is maintained through offerings, rituals, and continued karmic relationship.

Three major types

From these distinctions emerge three broad and overlapping categories of Dharmapālas:

- Converted spirits: These include once-hostile local gods, demons, or nature entities who were ritually subdued and transformed into protectors. Śrī Devī (Palden Lhamo in Tibet) and certain forms of Mahākāla fall into this category. Their ferocity is retained but redirected in service of the Dharma.

- Wrathful emanations of enlightened beings: These Dharmapālas are not beings of lower spiritual attainment, but deliberate manifestations of Buddhas or Bodhisattvas appearing in terrifying form. Yamāntaka, the wrathful aspect of Mañjuśrī, and Vajrapāṇi are prominent examples. Their wrath expresses wisdom and compassion aimed at cutting through the densest ignorance.

- Assimilated folk deities: As Buddhism spread across Asia, it encountered diverse indigenous traditions. Many local guardian spirits, warrior gods, or protective ancestors were incorporated into the Buddhist cosmos and reinterpreted as Dharmapālas. This category is especially prevalent in East and Southeast Asia, where figures like Guan Yu or village tutelary spirits were adopted as protectors of temples and teachings.

These typologies are not rigid. A single figure may fall into multiple categories depending on the tradition, region, or interpretive lens. What unites all Dharmapālas, however, is their protective function, a form of wrathful compassion that defends the conditions of awakening in a world marked by volatility and obscuration.

Major Dharmapālas across traditions

The concept of Dharmapālas manifests in varied forms across Buddhist cultures, reflecting regional adaptations, indigenous influences, and the doctrinal orientation of each tradition. While the core function, protecting the Dharma, remains consistent, the specific figures, their attributes, and ritual roles differ across geographical contexts.

Tibetan tradition

Tibetan Buddhism features the most elaborate and systematically integrated pantheon of Dharmapālas. Among the most prominent is Mahākāla, a wrathful emanation of Avalokiteśvara or Vajradhara, often depicted with multiple arms, trampled enemies, and flaming halos — symbols of his power to destroy ignorance and karmic obstacles. Palden Lhamo (Śrī Devī), the only female among the Eight Guardians of the Dharma in Tibetan Buddhism, is considered a fierce but maternal figure, said to ride a mule across a sea of blood and wield terrifying weapons — all in defense of the teachings.

Yamāntaka, a wrathful form of Mañjuśrī, exemplifies the tantric paradox of defeating death (Yama) through death-like intensity. Vajrapāṇi, another important figure, embodies the wrathful aspect of the Buddha’s power, serving as a fierce protector of tantric teachings. Tibetan Buddhism also integrates local protector spirits, such as the Nechung Oracle, a state-protector deity whose medium historically advised the Dalai Lama. These local beings were ritually subdued and bound by oath to act in service of the Dharma.

Chinese tradition

In Chinese Buddhism, Dharmapālas often derive from both Buddhist and Daoist sources. Skanda and Wei Tuo are commonly depicted as armored generals standing near temple entrances, guarding the Dharma with sword and shield. They serve not only as spiritual guardians but as moral exemplars of discipline and loyalty. Guan Yu, a deified historical general from the Three Kingdoms era, was assimilated into Buddhist temples as a protector figure, representing valor, righteousness, and unwavering commitment to truth. These figures typically perform less esoteric functions than their Tibetan counterparts but remain integral to temple ritual and iconography.

Japanese tradition

Japan inherited many of its protector deities from the Chinese Buddhist and esoteric (Shingon) traditions, often blending them with Shintō beliefs. Among the most venerated is Fudō Myōō (Acala), an immovable wisdom king depicted holding a sword and rope, surrounded by fire. He symbolizes the destruction of ignorance and the subjugation of negative forces. Bishamonten, originally a war god from Indian and Central Asian traditions, protects the Dharma by enforcing discipline and bestowing prosperity. Daikokuten, though associated with wealth and household protection, is also revered in some temples as a protector of the Dharma’s material foundations.

Southeast Asian variants

In Theravāda Buddhist cultures such as Thailand, Cambodia, and Myanmar, Dharmapāla figures are less centrally codified but still present. Guardian spirits known as nats in Myanmar or phi in Thailand are often syncretized with Buddhist cosmology. While these figures do not always match the tantric Dharmapālas in doctrinal complexity, they serve practical roles as defenders of temples, protectors of monastics, and agents of karmic retribution. Regional deities and animistic beings are integrated through local rituals, reflecting a Buddhism that is culturally embedded and ritually adaptive.

Across all these traditions, the Dharmapāla figures illustrate how Buddhism has preserved its central teachings while adapting to diverse cultural environments. Their varied forms and narratives provide a vivid lens into how protection of the Dharma is imagined, invoked, and embodied across the Buddhist world.

Dharmapālas and the problem of wrath

One of the most striking features of Dharmapāla iconography is its visual intensity: bulging eyes, snarling mouths, weapons, flames, and skull ornaments. These images depart sharply from the serene and gentle depictions of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas that many associate with Buddhist art. For modern observers — and even for some traditional practitioners — the wrathful appearance of Dharmapālas can provoke discomfort and confusion. How can such terrifying forms be reconciled with a tradition grounded in compassion, non-harming, and inner peace?

From a doctrinal standpoint, the wrath of Dharmapālas is not rooted in hatred or aggression but is understood as an expression of enlightened compassion. This paradox, that wrath can be compassionate, lies at the heart of tantric ethics. In Vajrayāna, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas manifest in wrathful forms when gentle means are insufficient to remove deeply rooted delusions. Like a fierce but caring teacher or a physician who must administer painful treatment to save a life, the wrath of a Dharmapāla is directed solely at the causes of suffering, never at sentient beings themselves. It is compassionate in aim, ruthless only in its method.

This perspective challenges conventional ethical categories. Buddhist morality is often associated with non-violence (ahiṃsā), patience, and loving-kindness. Yet the existence of wrathful deities who carry weapons and display terrifying power raises important questions: do Dharmapālas violate the spirit of Buddhist ethics? The traditional answer lies in the doctrine of skillful means (upāya). According to this principle, awakened beings use whatever methods are most effective to help sentient beings awaken. Sometimes that involves soothing comfort; other times, it involves shock, confrontation, or symbolic threat. The key criterion is not the appearance of the act but its motivation and result.

Wrathful Dharmapālas therefore function as extensions of the Bodhisattva vow, the commitment to liberate all beings, no matter the cost to oneself or the form the intervention takes. They are protectors not only of texts and temples but of the mental clarity and moral courage required to stay on the path. Their frightening imagery serves a purpose: it cuts through spiritual complacency, reminds practitioners of the urgency of liberation, and mirrors the inner confrontation with one’s own defilements.

In this way, the wrath of Dharmapālas does not contradict Buddhist ethics but deepens it. It illustrates a mature ethical stance that goes beyond passive tolerance, recognizing that genuine compassion sometimes requires intensity, discipline, and even symbolic violence — never against persons, but against the ignorance that binds them.

Ritual and practice

The Dharmapālas are not merely mythic figures or doctrinal concepts; they are living presences within the ritual life of Buddhist communities, particularly in tantric and Vajrayāna traditions. Their power is accessed, reaffirmed, and maintained through specific ritual forms that range from elaborate protector pujas to daily recitations, visualizations, and offerings. These practices serve both as devotional expressions and as transformative methods aimed at purifying perception, fortifying ethical resolve, and dispelling both external and internal obstacles.

One of the most prominent modes of Dharmapāla engagement is through ritual invocation, particularly within the context of tantric sādhanā (spiritual practice). Here, wrathful protectors are visualized as part of a mandala, integrated into a sequence of meditative phases that include generation, dissolution, and identification. The practitioner may visualize the protector in vivid detail such as flaming hair, skull ornaments, trampling the forces of delusion — and merge their own awareness with the deity’s fierce, non-dual clarity. These practices are not designed to arouse fear or aggression but to awaken the fearless precision needed to confront one’s own attachments and obscurations.

Protector pujas (Tibetan: khandro chöpa or gektor) are another central element of Dharmapāla worship. Performed in monasteries and retreat centers, often on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis, these ceremonies involve ritual offerings, mantra recitations, and specific chants designed to reaffirm the Dharmapāla’s role and renew the practitioner’s vow-bound relationship with them. In these pujas, wrathful deities are offered symbolic gifts such as torma (ritual cakes), incense, and alcohol — not as indulgence, but as tokens of respect and obligation. Such rituals both honor the protector’s presence and fulfill the karmic commitments that bind them to serve.

These commitments are not one-sided. In Vajrayāna Buddhism, the relationship between practitioner and Dharmapāla is often formalized through vows known as samaya. These sacred commitments ensure that the protector will guard the practitioner as long as the practitioner maintains ethical conduct, keeps their vows, and respects the sanctity of the Dharma. Breaking samaya is believed to weaken this bond, potentially leading to misfortune or spiritual regression. Thus, Dharmapāla practice is not merely a matter of belief, but of mutual responsibility grounded in ritual and ethical discipline.

At the individual level, protective mantras and visualizations form an accessible layer of Dharmapāla practice. Reciting the mantra of Mahākāla, for example, or mentally picturing oneself surrounded by the blazing energy of Vajrapāṇi can serve as powerful supports for courage, moral focus, and clarity. These acts are often part of daily practice, woven into morning or evening liturgies, and used as stabilizing resources during times of fear, doubt, or spiritual stagnation.

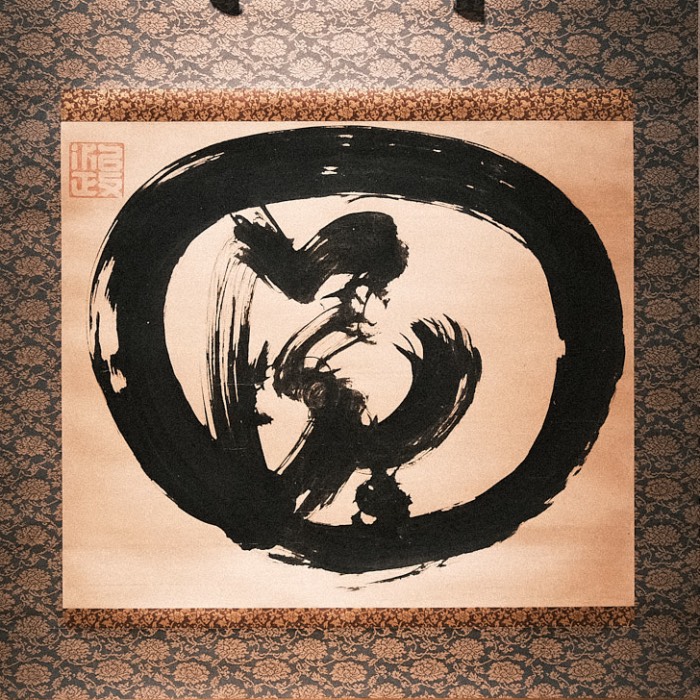

In monastic settings, Dharmapālas are regularly invoked to guard the sangha and its ritual boundaries. Their images often occupy prominent places at monastery entrances or within protector chapels, where monks offer prostrations or perform short liturgies. For laypeople, Dharmapālas may serve as accessible icons of protection: household shrines, painted scrolls (thangkas), or amulets inscribed with protective mantras provide tangible connections to the fierce wisdom of these deities.

In all these contexts, the ritual role of Dharmapālas is not to dominate or control, but to protect the conditions under which awakening can occur. Their fierce forms act as guardians of moral clarity and spiritual focus, ensuring that the practitioner remains oriented toward liberation even in the face of distraction, fear, or chaos. In this sense, Dharmapāla practice is as much about internal discipline as it is about external protection. It binds the practitioner to the Dharma not through submission, but through an energetic commitment to vigilance, integrity, and fearless compassion.

Symbolism and interpretation

The imagery and roles of Dharmapālas are rich with symbolic meaning. Their fierce appearances, ritual functions, and doctrinal positioning invite layered interpretation, from inner psychological readings to socio-political analyses. Rather than being mere supernatural beings, Dharmapālas can be seen as multidimensional constructs reflecting the dynamics of the human mind, the needs of Buddhist institutions, and the power of myth in shaping ethical and spiritual commitments.

Psychological Reading: Guardians of inner discipline

From a psychological perspective, Dharmapālas embody the energies required to overcome inertia, delusion, and moral compromise. Their wrathful forms are not externalized threats but inwardly projected forces — personifications of the clarity, courage, and discipline needed to confront our own defilements. Just as peaceful Buddhas represent the culmination of wisdom and compassion, wrathful protectors can be understood as guardians of the path toward such realization. They arise in moments of internal struggle, when one’s resolve falters or when habits resist transformation.

In meditation, for example, the image of a Dharmapāla may serve as a mirror for the practitioner’s own latent energy — a symbol of unflinching commitment to truth. Visualizing a protector trampling the demons of ignorance or wielding fire to consume illusion is not about encouraging aggression, but about harnessing determination and ethical rigor. In this light, Dharmapālas function as archetypes of psychological integrity: fierce not because they are hateful, but because the path to liberation sometimes demands intensity and confrontation with what is difficult or painful.

Political and institutional role: Legitimizing authority

Dharmapālas also serve institutional functions within Buddhist history. As guardians of temples, lineages, and teachings, they have been employed to reinforce religious authority and delineate the boundaries of orthodoxy. Their presence in monastery entrances, prayer halls, and tantric rituals signals not only protection from spiritual obstacles, but also from doctrinal deviation or external challenge.

In Tibetan Buddhism, for example, state protectors such as Nechung were invoked in political affairs, offering oracular counsel to the Dalai Lama. The integration of protector spirits into the institutional framework helped to legitimate the spiritual and temporal authority of monastic leadership. In this context, Dharmapālas can be seen as tools of cohesion and continuity, reinforcing the sanctity of the Dharma and the structures that uphold it.

Their symbolic violence thus serves a dual function: internally as moral vigilance, and externally as defense against chaos or dissent. This duality reflects the broader Mahāyāna concern with both personal liberation and the protection of conditions under which all beings can pursue awakening.

Myth and metaphor: Taming the wild mind and the world

At a mythic level, the stories of Dharmapālas often involve themes of conversion, subjugation, and oath-taking. Formerly wild or malicious beings are subdued by enlightened masters and bound by vow to protect the Dharma. These narratives are not merely supernatural tales but encode deep metaphors for spiritual transformation.

The wild deity tamed by a master represents the unruly forces of the mind — fear, pride, craving — that, once confronted and understood, can be redirected toward constructive ends. The vow to protect the Dharma symbolizes the ethical commitment that emerges from insight: once we see clearly, we take responsibility for guarding what is wholesome and true.

These myths also reflect how Buddhism has historically encountered and incorporated indigenous deities and beliefs. Rather than rejecting local spirits outright, it absorbed them into a new ethical framework, transforming them into Dharmapālas. This process mirrors the inner work of integrating shadow aspects of the psyche, not by suppression, but by redirection and discipline.

In sum, the symbolism of Dharmapālas operates on multiple levels: they are psychological guardians of clarity, institutional enforcers of ethical boundaries, and mythic figures encoding the drama of inner and cultural transformation. Their wrath is not a deviation from compassion but one of its most paradoxical and potent expressions.

Contemporary relevance

While the imagery and mythology of Dharmapālas might appear distant from contemporary concerns, their symbolism and functions continue to hold relevance in modern Buddhist practice — and beyond. In both traditional and adapted forms, Dharmapālas continue to shape how individuals and communities navigate spiritual discipline, ethical resolve, and cultural identity in a rapidly changing world.

Living ritual and tantric continuity

In Vajrayāna communities, particularly in Tibetan Buddhism, Dharmapālas remain central to ritual life. Protector pujas are still performed daily in monastic settings, especially in the early morning, to invoke the energy of specific Dharmapālas for the safeguarding of teachings and the dispelling of obstacles. Practitioners may develop personal connections with certain protectors through empowerment rituals, guided visualizations, or mantra recitation. For them, the Dharmapāla becomes a companion on the path, not only a symbolic archetype but an intimate force aiding in ethical vigilance and inner transformation.

In this sense, Dharmapālas serve as a bridge between doctrinal transmission and lived practice. They maintain the continuity of tantric methods by linking practitioner and lineage, past and present. The rituals associated with Dharmapālas remind contemporary Buddhists that spiritual insight is not only cultivated through contemplation and compassion, but also through energetic clarity and protection of moral boundaries.

Psychospiritual and therapeutic resonance

Outside of strictly religious contexts, the iconography and symbolism of Dharmapālas resonate with modern psychological and therapeutic frameworks. Their wrathful appearances, with glaring eyes, bared teeth, and flaming halos, can be interpreted as expressions of the “fierce guardian” within the psyche: the inner faculty that protects integrity, truth, and conscious transformation against the forces of denial, fear, or self-deception.

In mindfulness and psychotherapeutic contexts, practitioners often speak of the importance of “boundaries”, “self-compassion with clarity”, or “non-negotiable ethics.” These ideas parallel the function of Dharmapālas as inward protectors: fierce not because they are violent, but because they defend against regressions into unwholesome habits. Some contemporary Buddhist teachers have even described the invocation of wrathful protectors as a way of psychologically confronting difficult emotions, internalized oppression, or the fear of change.

This psychospiritual reading aligns Dharmapālas with Jungian archetypes or parts-based models such as Internal Family Systems (IFS), wherein even the most aggressive inner figures are ultimately protectors misunderstood or misaligned. In this way, modern psychology reinterprets Dharmapālas not as relics of superstition, but as symbols of inner power and transformation.

Cultural identity and postcolonial assertion

For Buddhist communities in exile or diaspora, such as the Tibetan exile community, Dharmapālas also play a role in preserving cultural identity and spiritual sovereignty. The rituals surrounding state protectors like Nechung are not only religious acts but affirmations of continuity and resilience in the face of political displacement. The persistence of protector worship becomes a cultural act: an assertion that the Dharma and its guardians endure even under threat.

Similarly, in regions where Buddhism was historically marginalized or colonized, the revival of Dharmapāla rituals can serve as a reclaiming of indigenous spiritual heritage. In this light, Dharmapālas are not just metaphysical guardians, but also cultural sentinels, preserving local expressions of Buddhism from erasure and homogenization.

Adaptation and global practice

As Buddhism continues to spread and adapt in the West and other global contexts, Dharmapālas present both a challenge and an opportunity. On the one hand, their wrathful forms can appear at odds with modern sensibilities that favor psychological gentleness or secular spirituality. On the other hand, they invite practitioners to reconsider the complexity of compassion, to recognize that fierce clarity, discipline, and protective energy are not contradictory to love, but essential expressions of it.

Some Western teachers have begun to reframe Dharmapālas as inner energies or symbolic guardians of integrity. Others maintain traditional rituals in adapted formats, allowing modern practitioners to engage with their transformative power without requiring a wholesale adoption of foreign cosmologies. In artistic circles, Dharmapālas have inspired contemporary visual art, performance, and meditation techniques that engage with their symbolism in fresh ways.

In all these adaptations, what remains is the core intuition that the path of awakening must be protected — from distraction, from delusion, and from dilution. Whether as deity, archetype, or metaphor, the Dharmapāla reminds us that liberation requires guardianship.

Conclusion

Dharmapālas represent one of the most complex and multilayered categories within Buddhist tradition. As wrathful protectors of the Dharma, they defy simplistic classifications: they are not divine enforcers in a theistic sense, nor are they purely mythic or psychological projections. Instead, they function as highly adaptive symbols and ritual presences whose role spans metaphysical, ethical, and socio-cultural domains.

Dharmapālas have developed from their origins as converted spirits, wrathful emanations, and folk deities to their integration into distinct regional traditions across Asia. These figures display significant variety, yet they are unified by a core function: to protect the path to awakening. Whether guarding monasteries, subduing inner defilements, or maintaining the ritual integrity of tantric practice, Dharmapālas are invoked to preserve the conditions necessary for Buddhist liberation.

This leads to their deeper soteriological significance. In Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna frameworks, liberation is not solely a matter of private insight but involves sustained ethical conduct, clarity of purpose, and protection against the forces, both internal and external, that obstruct awakening. Dharmapālas serve this function in three ways. First, ritually: they are present in pujas and sādhanās that reaffirm commitment to the path. Second, ethically: their wrathful forms serve as reminders that discipline and moral courage are necessary components of compassion. Third, psychologically: they symbolize the internal faculties of vigilance, determination, and integrity that are indispensable in confronting delusion.

Far from being contradictions to Buddhist ethics, Dharmapālas clarify its full scope. Compassion is not always gentle; it sometimes requires firmness, boundary-setting, and confrontation with destructive patterns. The Buddhist doctrine of skillful means provides the philosophical basis for this fierceness — wrath not as aggression, but as a method for cutting through resistance when subtler methods fail.

In contemporary settings, Dharmapālas continue to evolve. For traditional communities, they safeguard continuity and serve as ritual anchors. For modern practitioners and interpreters, they offer symbolic resources for engaging moral complexity, psychological resilience, and cultural survival. This versatility underscores their ongoing relevance: Dharmapālas are not archaic relics of esoteric cosmology but expressions of a fundamental insight: that the path to awakening must be protected, cultivated, and sometimes fiercely defended.

Ultimately, the Dharmapāla is not an external savior but a figure that confronts the practitioner with a question: What must be defended in your own life for wisdom to emerge? In this light, the wrathful protector is not a spectacle to be feared or venerated uncritically, but a mirror of the intensity and clarity that the path demands.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments