Buddhist hells

Among the many symbolic constructs in Buddhist cosmology, the depiction of hells (naraka) stands out for its vivid imagery and moral intensity. Often characterized by scenes of torment, fire, ice, and punishment, these realms challenge modern readers to ask: are these descriptions to be taken literally, or do they function symbolically? Are Buddhist hells metaphysical places, psychological states, or narrative devices to encourage ethical behavior?

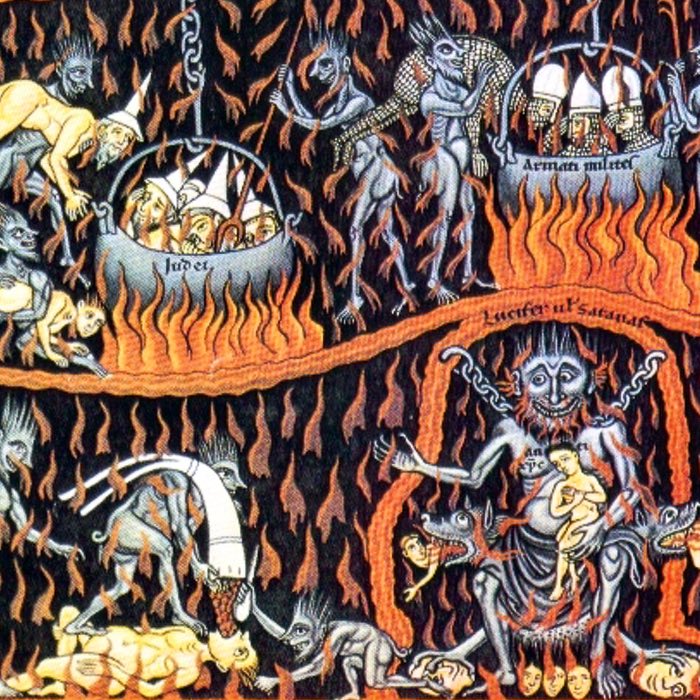

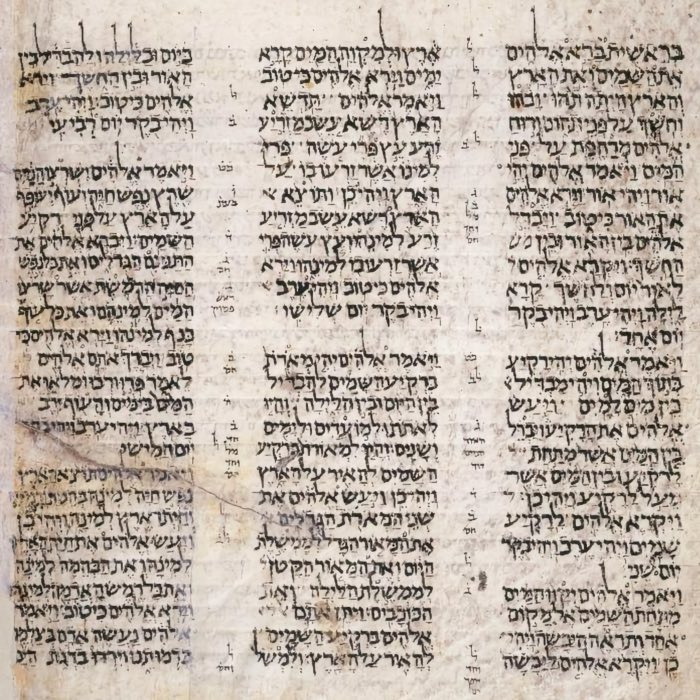

Excerpt from a Thai Pāli manuscript, depicting the Buddhist hells and their inhabitants, illustrating the consequences of immoral actions. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY 4.0)

In this post, we approach the Buddhist hells not as dogmatic assertions of an afterlife realm, but as complex representations embedded in a broader framework of karmic causality, ethical reflection, and soteriological concern. In doing so, we situate the hells within the tradition’s layered hermeneutics: as real in their karmic consequences, impermanent in duration, and symbolic in function. Rather than being governed by divine wrath, these realms are shaped entirely by the moral quality of past actions. They are, in a sense, ethical landscapes produced by karma itself.

Understanding the Buddhist hells requires attention to the interplay between myth, ethics, and practice. Far from being static depictions of punishment, the hells illustrate the consequences of harmful actions and the urgency of transformation. They serve as moral warnings, meditative reflections, and, in some schools, as spaces into which Bodhisattvas willingly descend to offer aid. This multilayered role makes the Buddhist hells not only doctrinally significant but also spiritually and psychologically resonant across historical and cultural contexts.

Overview of Buddhist hells

In Buddhist cosmology, the concept of hell is referred to by the term naraka in both Sanskrit and Pāli. Unlike the eternal damnation found in some theistic traditions, naraka denotes a set of realms characterized by intense suffering, caused not by divine judgment but by the inexorable consequences of one’s own actions. These realms are neither eternal nor final; they are transient destinations shaped entirely by negative karma and are left behind once that karma has been exhausted.

The number and classification of these hells vary across Buddhist traditions. In Theravāda Buddhism, traditional cosmological texts describe eight hot hells and eight cold hells, with each realm progressively more severe than the last. Additionally, there are subsidiary or “neighboring” hells that surround the main ones, reserved for those whose actions do not fit neatly into a single karmic outcome. Mahāyāna sources often expand these descriptions, including additional narrative detail and moral nuance, sometimes portraying beings who suffer for both personal and collective karmic causes. In Vajrayāna, the hells may also appear in visionary and ritual contexts, as symbolic fields to be purified or traversed through tantric practice.

These hells are not isolated constructs but are fully embedded within the broader Buddhist cosmological model of the six realms of rebirth, which include the realms of gods (devas), demi-gods (asuras), humans, animals, hungry ghosts (pretas), and hell beings (narakas). Specifically, the various hot and cold hells described in Buddhist texts constitute the domain of the naraka realm, the sixth and lowest of the six realms.

Despite the variety, a shared doctrinal foundation unites these representations: the hells are temporary states of existence brought about by morally destructive actions such as killing, lying, or cruelty. They function not as sentences but as consequences. As such, they serve not to condemn but to illustrate the logic of karmic causation — a system in which actions have results proportionate in quality, though not necessarily in time. In this way, the Buddhist hells represent both an ethical mirror and a warning: they do not await sinners but arise from what one has already become.

Structural and symbolic dimensions

The architecture of Buddhist hells is both complex and symbolically charged. Descriptions in classical texts, such as the Pāli Canon’s Visuddhimagga, the Abhidharmakośa of Vasubandhu, and the Mahāyāna sutras like the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, outline a detailed geography that includes multiple categories of suffering realms, most prominently the eight hot hells and the eight cold hells. The hot hells, such as Saṅghāta and Mahāraurava, are filled with fire, molten metals, and physical dismemberment, symbolizing the intense agony produced by hatred and violence. The cold hells, by contrast, subject beings to freezing temperatures and skin-splitting frost, reflecting the isolation and emotional coldness of karmic aversion. These hells are often imagined as situated beneath the earth or in distant subterranean regions, with distinct vertical and horizontal arrangements that symbolize the gradation and inevitability of karmic consequence.

Many of these realms are further subdivided into peripheral or neighboring hells, which represent specific karmic misdeeds or distorted mental states. Guardians and punitive agents, sometimes interpreted as karmic projections, populate these realms, carrying out punishments not arbitrarily but in exact accordance with the causal imprint of one’s past actions. These figures may be personified or symbolic, embodying the precision of karmic law. In some traditions, beings like Yama, the so-called Lord of Death, appear not as gods in the theistic sense, but as archetypal judges or mirrors of the mind. In Tibetan texts, Yama is often depicted holding a mirror that reflects one’s karmic history, emphasizing self-accountability rather than divine retribution.

This structure illustrates a key doctrinal point: suffering in the hells arises solely from one’s own karma, not from divine punishment or moral retribution imposed by an external agent. The Buddhist hells are ethically structured environments where the intensity and nature of the suffering directly correspond to the intentions and gravity of one’s actions. In this sense, they operate as visual and narrative metaphors for the psychological and existential consequences of moral failure.

Art and ritual have played an important role in reinforcing these symbolic functions. From East Asian temple murals to Tibetan thangka paintings, depictions of hells have been used to educate, warn, and prompt ethical introspection. Ritual recitations and liturgies often invoke these images to generate remorse, encourage restraint, or inspire compassionate action. Thus, the structure of the Buddhist hells, both literal and symbolic, is not merely cosmological speculation, but an ethical and spiritual map designed to guide beings away from harm and toward liberation.

Interpretations across schools

Interpretations of the Buddhist hells differ across the major Buddhist traditions, each emphasizing distinct aspects of their ethical, symbolic, and soteriological meaning. While all traditions accept the basic framework of karmic consequence and temporary suffering, the function and significance of the hells are read through different doctrinal lenses.

In the Theravāda tradition, the hells are often interpreted as both cosmological and psychological domains. The emphasis tends to be on ethical causality: rebirth in a hell realm results from severe immoral actions such as killing or cruelty, especially when motivated by hatred. The depictions of hell in Pāli texts like the Devadūta Sutta (AN 3.36) serve as vivid moral warnings, designed to instill fear of misconduct and promote virtuous behavior. At the same time, some modern Theravāda teachers also emphasize the internal dimension of these realms, suggesting that hell-like experiences reflect states of mind dominated by aversion and mental suffering.

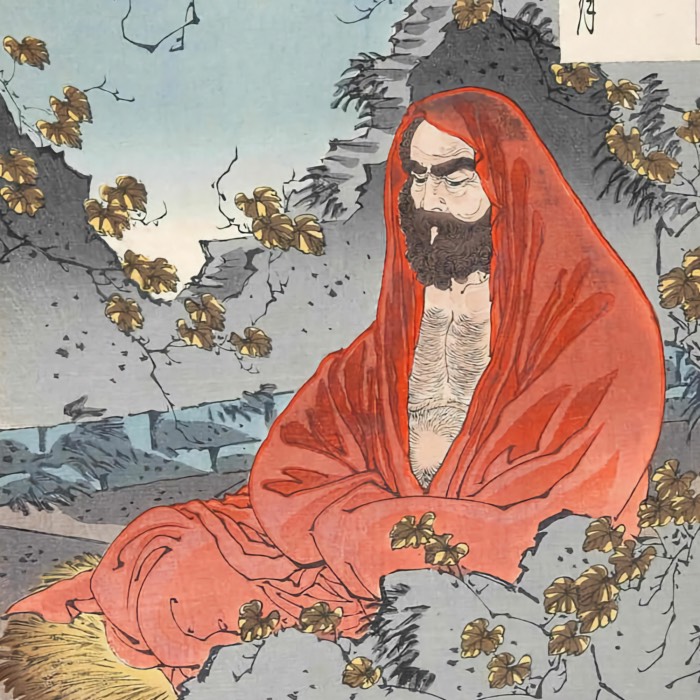

Mahāyāna Buddhism incorporates the idea of upāya (skillful means), which allows for a more fluid and symbolic understanding of the hells. While karmic consequence remains real, the hells are also interpreted as pedagogical spaces — places where even great Bodhisattvas may descend in order to assist and liberate suffering beings. The Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha (Jizō in Japanese), for instance, is famously committed to postponing his own final awakening until the hells are emptied. In this view, the hells serve not only as warning but as arenas for compassion in action. They become part of the Mahāyāna vision of boundless altruism.

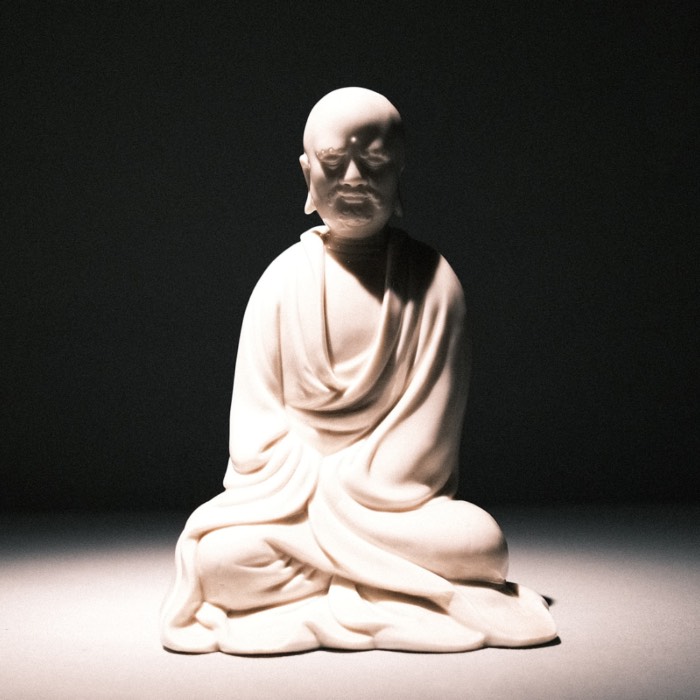

In Vajrayāna Buddhism, hell realms are often integrated into visionary and meditative practice. Here, the hells can appear in wrathful forms, either as external visions during states of bardo (intermediate existence) or as internal experiences during advanced tantric meditation. Wrathful deities such as Yamāntaka or Mahākāla may embody the energetic force needed to cut through deep-seated delusion, including the karmic seeds that give rise to hellish experiences. In this tradition, hell is not merely a place to be avoided but a reality to be transformed through direct experiential confrontation, often interpreted as purification or the re-integration of obscured awareness.

Across these schools, the Buddhist hells are not uniform in meaning. They serve as warnings, ethical mirrors, realms of compassion, and transformative visions — each interpretation rooted in its own soteriological and philosophical outlook.

Comparison with Abrahamic concepts of hell

Having mapped the internal diversity, how does the Buddhist concept of hell differ — or overlap — with hell concepts in other religions? To clarify this, let us compare the Buddhist understanding with more familiar frameworks in a brief excursus into the three major Abrahamic religions.

The Buddhist understanding of naraka differs markedly from the hell traditions found in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, even though all draw on imagery of fire, torment, or separation to communicate ethical gravity. The key differences concern metaphysics (karmic causation vs. divine judgment), duration, function, and institutional use.

Judaism

Early Hebrew scriptures speak of Sheol as a shadowy abode of the dead, a realm of silence where all souls descend regardless of moral standing. Sheol was not originally a punitive place but an existential horizon of mortality. Over time, especially in apocalyptic literature of the Second Temple period, the notion of Gehenna emerged, often associated with the Valley of Hinnom outside Jerusalem — a place tied to idolatry and child sacrifice. Gehenna came to symbolize fiery retribution for the wicked and purification for some, linking afterlife destiny to divine judgment and covenantal fidelity. Rabbinic Judaism preserved a range of interpretations: for some, Gehenna is a temporary purgative state lasting twelve months; for others, a more enduring punishment awaits those who reject God’s covenant. Unlike Buddhist naraka, which functions as an impersonal consequence of karma, Jewish notions of hell remained tied to the covenantal relationship with God and the fate of Israel.

Christianity

In Christianity, the concept of hell developed into one of the most vivid and consequential doctrines of the tradition. Drawing on Jewish apocalypticism, Greco-Roman underworld myths, and later theological speculation, hell became the eschatological consummation of divine justice for those who reject grace. Patristic and scholastic writers debated its nature: figures like Tertullian and Augustine of Hippo emphasized eternal conscious torment, while others such as Origen of Alexandria interpreted hell more as separation from God or even a temporary purgative state leading ultimately to universal restoration (apokatastasis). A minority tradition, represented later by Arnobius of Sicca, explored annihilation of the wicked. By late antiquity, especially through the influence of Augustine, the conviction that hell’s punishments were eternal became dominant.

Beyond theology, hell became a tool of ecclesial power. As explored in our earlier article on “The concept of hell and its instrumentalization by the Church”, fear of damnation was used to enforce obedience, with excommunication operating as social and spiritual death. The rise of purgatory intensified this system, tying salvation to indulgences, penance, and sacramental participation. Graphic medieval imagery — flames, demons, torture — reinforced this regime of fear, often eclipsing the New Testament’s message of love. Unlike Buddhist hells, which are temporary and karmic in origin, the Christian hell became eternal, absolute, and bound to institutional authority.

Islam

In Islam, the Qurʾān presents Jahannam as a place of fire, torment, and gradated punishment. The descriptions are vivid: scorching winds, boiling water, and guardians who enforce divine justice. Yet alongside this severity, the Qurʾān also emphasizes God’s mercy and the possibility of redemption. A theological distinction developed: unbelievers (kuffār) face eternal punishment, while sinful Muslims may eventually leave Jahannam after purification, entering paradise through God’s mercy and the Prophet’s intercession. Islamic thought thus combines the certainty of divine justice with the hope of divine compassion. Unlike Buddhism, where karmic law is automatic and impersonal, Islamic eschatology is decisively relational — framed by God’s will, accountability on the Day of Judgment, and the balance of deeds.

Core contrasts

In Buddhism, hells are finite states within saṃsāra, produced and exhausted by karma, and even open to Bodhisattva intervention. In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, hell is primarily adjudicative and eschatological, grounded in God’s judgment, covenant, and mercy, with enduring or eternal consequences in many strands. Taken together, these contrasts show a fundamental divergence: in the Abrahamic traditions, hell marks the final — and often eternal — verdict of divine judgment; in Buddhism, hells are temporary karmic consequences meant to educate, transform, and keep liberation within reach.

The Buddhist hell as soteriological narrative

Having compared Buddhist hells with the Abrahamic frameworks, we now return to their internal logic: what these realms do for practice, ethics, and liberation.

The Buddhist hells are not simply fearsome cosmological locales but play an integral role in the tradition’s soteriological vision — the path to liberation from suffering. Through their graphic detail and emotional intensity, the hell realms function as didactic devices that vividly illustrate the moral consequences of harmful actions. Their primary pedagogical effect is to induce a sense of ethical gravity and personal responsibility. Rather than condemning the individual, the hells reveal what one becomes through habitual greed, hatred, and delusion.

This narrative of cause and consequence is reinforced by the underlying doctrine of impermanence. Hells are not eternal abodes but temporary states conditioned by karma. No being is doomed indefinitely, and the very suffering experienced in these realms serves as a potential catalyst for remorse, purification, and future moral clarity. Rebirth into more favorable conditions remains possible once the negative karmic potential is exhausted, affirming the Buddhist principle that liberation is never foreclosed.

Moreover, in Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions, the hells become not just destinations to avoid, but realms of compassionate engagement. The Bodhisattva’s vow, to liberate all beings regardless of the cost, includes a readiness to enter the hell realms voluntarily. Figures like Kṣitigarbha embody this radical altruism, descending into the depths of suffering to aid those unable to help themselves. In this way, hells are recast as spaces of salvific intervention, not abandonment.

Finally, some schools interpret hell not as an external place but as a mode of experience. From this view, hellish states can manifest in the present — in moments of intense fear, hatred, guilt, or alienation. These interpretations highlight that liberation does not necessarily require changing location but transforming perception and intention. In this light, the Buddhist hells, whether envisioned as realms, metaphors, or psychological conditions, underscore the urgency of the path and the possibility of freedom for all beings.

Modern reception and reinterpretation

In modern contexts, especially among secular and globally engaged Buddhist communities, the traditional imagery of Buddhist hells has been met with a variety of interpretive strategies. A prominent approach, often discussed in the context of Buddhist-informed psychotherapy and contemplative philosophy, is to understand the hell realms as cognitive-affective states — temporary yet powerful manifestations of the mind shaped by aversion, fear, hatred, or remorse. In this view, hell is not a physical postmortem realm, but a psychological condition that can arise in ordinary life and be observed directly in meditative practice. For example, intense emotional turmoil or mental anguish may be recognized as momentary descents into naraka-like states. This psychological reading allows practitioners to maintain fidelity to the ethical message of karmic causation while eschewing metaphysical literalism.

In addition to psychological interpretations, Buddhist hells have also found expression and reinterpretation in modern artistic, cinematic, and literary media. Visual artists and filmmakers have drawn on the intense imagery of the hell realms to evoke existential suffering, social injustice, or psychological trauma. In Japanese manga and anime, in contemporary Tibetan painting, and in Buddhist-inflected literature, hells are reimagined as both symbolic and critical tools, reflecting personal, societal, or spiritual breakdowns. Such representations extend the reach of Buddhist cosmology into new expressive forms, often foregrounding moral ambiguity or systemic violence as new causes of karmic descent.

Within contemporary Buddhist communities, the role of the hells remains ethically potent. Teachers may use the imagery of hell to provoke moral reflection, especially regarding actions that harm others, the environment, or the integrity of the Dharma. In some cases, references to hell serve as rhetorical devices to encourage ethical restraint, compassion, or ecological awareness. In others, they are used to highlight the structural suffering embedded in modern social systems — poverty, war, addiction — framing them as collective karmic conditions that mirror the traditional descriptions of the narakas.

Far from being discarded, the myth of Buddhist hells continues to evolve. Whether as internal states, cultural metaphors, or ethical warnings, they remain part of Buddhism’s adaptive vocabulary, linking ancient cosmology with modern existential insight.

Conclusion

The Buddhist hells, while often visually disturbing and emotionally charged, play a nuanced and essential role within the broader architecture of Buddhist thought. They offer a symbolic and cosmological means of expressing the gravity of ethical choices and the inner logic of karmic causality. These realms, far from being metaphysical dogma or threats of divine punishment, function as pedagogical landscapes — vivid dramatizations of what it means to live unethically and what forms suffering can take when shaped by aversion, hatred, or delusion.

Rather than presenting damnation as an absolute, Buddhist cosmology envisions the hells as impermanent states, conditioned by past actions and open to change through purification, ethical realignment, and compassionate intervention. This reflects a deeper integration of mythology and soteriology: the hells are not mere scare tactics but stages on a dynamic path, emphasizing that even the most extreme suffering remains within the realm of karmic law and therefore within the scope of liberation.

In this way, the hells function not only to warn but to awaken. They challenge practitioners to cultivate moral clarity, emotional accountability, and the resolve to transform harmful tendencies before they bear painful fruit. At the same time, they provide a setting for the profound moral commitment of the Bodhisattva ideal: the willingness to descend into the depths of suffering for the sake of others.

Finally, in both traditional and modern contexts, the hells continue to shape the Buddhist moral imagination. Whether interpreted literally, symbolically, or psychologically, they serve to deepen compassion by offering an unflinching look at the consequences of harm and the urgency of ethical and spiritual practice. The Buddhist hells are not the endpoint of a path gone wrong, but a potent reminder that even in the darkest states, the potential for transformation endures.

References and further reading

- Matsunaga, Aliciam Matsunaga, Daigan, The Buddhist concept of hell, 1971, New York: Philosophical Library

- Teiser, Stephen F., Having Once Died and Returned to Life: Representations of Hell in Medieval China, 1988, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 48 (2): 433–464. doi: 10.2307/2719317ꜛ

- Law, Bimala Churn, Barua, Beni Madhab, Heaven and hell in Buddhist perspective, 1973, Varanasi: Bhartiya Pub. House

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments