Buddhist cosmology: Mount Meru and the Ocean of Milk

Buddhist cosmology presents a vision of the universe that is at once highly structured, mythically rich, and deeply symbolic. Central to this vision are two powerful images inherited and reformulated from the broader South Asian religious milieu: Mount Meru, the cosmic axis around which the universe revolves, and the vast encircling Ocean of Milk. These elements are not merely ornamental myths but form a foundational part of traditional Buddhist worldviews, appearing in canonical texts, commentarial literature, visual art, and ritual practice.

Mandala depicting Mount Meru as an inverted pyramid topped by a lotus, China, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), silk tapestry. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The image of Mount Meru, a golden mountain rising at the center of the world, functions not only as the axis mundi connecting heavens and underworlds but also as a spatial metaphor for spiritual hierarchy and karmic stratification. The surrounding Ocean of Milk demarcates the sacred geography of the four continents and serves as a liminal boundary between realms. Together, they form a cosmogram that embodies both vertical moral order and horizontal diversity of experience.

While these cosmological motifs may seem fantastical from a modern, scientific standpoint, they were never merely naïve descriptions of geography. Rather, they encode ethical principles, meditative insights, and philosophical frameworks. Their roots lie in early Vedic and Hindu cosmologies, but the Buddhist tradition reinterpreted them through a distinct soteriological lens: Mount Meru and the cosmic ocean became symbolic anchors for understanding the nature of perception, rebirth, and liberation.

In this post, we explore how these motifs function across Buddhist traditions, not simply as relics of pre-scientific thought, but as symbolic tools that continue to shape spiritual imagination, moral reflection, and cultural continuity.

Classical structure of the Buddhist universe

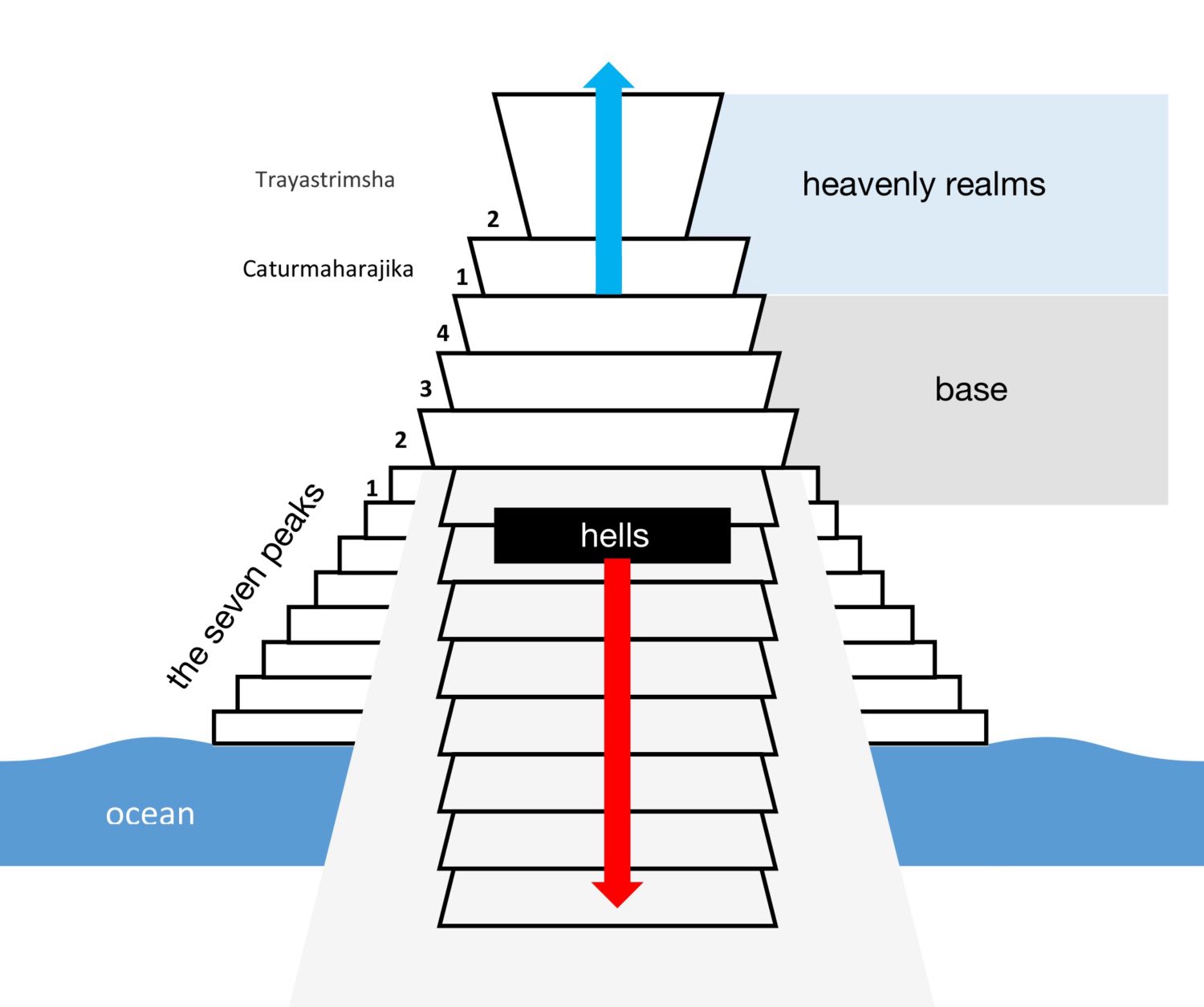

At the heart of classical Buddhist cosmology stands Mount Meru, envisioned as a vast, golden mountain at the very center of the universe. It is not merely a physical structure but a cosmological axis (axis mundi) that organizes the universe both vertically and horizontally. Vertically, it connects various planes of existence — the celestial realms above, the human and animal worlds at its base, and the hell realms below — thereby mapping karmic gradation onto spatial structure. Horizontally, it is surrounded by concentric rings of oceans and mountain ranges, and most prominently, the four great continents that form the known world from a Buddhist geographical perspective.

According to traditional models, including those found in the Abhidharmakośa of Vasubandhu and Pāli Canon commentaries like the Visuddhimagga, each of the four continents, Jambudvīpa (south), Pūrvavideha (east), Aparagodānīya (west), and Uttarakuru (north), lies on a cardinal point relative to Mount Meru. These are not real continents in the geographic sense, but symbolic constructs within the traditional Buddhist cosmological framework, a cardinal point relative to Mount Meru. Our own human world is located on Jambudvīpa to the south. Each continent is thought to be inhabited by different kinds of beings, with varying lifespans, moral dispositions, and karmic propensities, further emphasizing the moral structure of the cosmos. The ocean that encircles these continents, often referred to as the Ocean of Milk, serves not only as a physical delimiter but also a symbol of samsāric vastness and the fluid boundary between realms.

Above Meru are the successive heavenly realms, culminating in the Brahmā worlds and the immaterial attainments of the formless planes, which are accessible through advanced meditative states. Below lie the subterranean realms, including the various hells and ghost domains, corresponding to states of severe karmic affliction. This vertical stratification corresponds directly to moral and mental development: higher planes are inhabited by more refined, blissful beings; lower realms reflect coarser, more afflicted states of consciousness.

Diagram of the vertical structure of Mount Meru. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain; modified)

Thus, the classical Buddhist universe is not a neutral spatial model but an ethical topography. It maps inner mental states and karmic dynamics onto a structured cosmological vision, one that serves not only to describe reality but to orient practitioners toward ethical refinement and eventual liberation.

Mount Meru as symbolic geography

Beyond its cosmological role, Mount Meru functions as a powerful symbolic structure in Buddhist thought and practice. As the axis mundi, it connects the vertical realms of existence, from the highest heavens to the lowest hells, thereby modeling not only the ontological structure of the universe but also the internal terrain of spiritual ascent or descent. In this sense, Meru is not merely a physical feature but a symbolic map of consciousness, embodying both the stratification of karma and the potential for liberation.

In meditative and ritual contexts, Mount Meru frequently appears in cosmological diagrams, temple architecture, and mandala designs. In Tibetan and Vajrayāna Buddhism especially, it is visualized at the center of intricate mandalas, anchoring the practitioner’s orientation to the spiritual universe. These visualizations are not simply imaginative projections; they serve to realign the practitioner’s perception, placing the mind and body in alignment with a moral and cosmic order. In such settings, Mount Meru becomes an instrument for contemplative insight and spatial symbolism, grounding the practitioner in a vision of interconnectedness and transcendence.

Psychologically and ethically, Mount Meru operates as a metaphor for stability, centrality, and transcendence. Its unshakable presence at the center of the cosmos mirrors the aspirational qualities of meditative equanimity and moral resolve. Just as Meru stands unmoved while the world turns around it, the disciplined mind is envisioned as calm amidst the turmoil of saṃsāra. Moreover, Meru’s vertical structure reflects the ethical logic of Buddhist cosmology: moral ascent leads toward clarity and compassion, while moral descent results in confusion and suffering.

Thus, Mount Meru is not merely a feature of mythic geography but a symbolic and contemplative focal point. It fuses metaphysical vision with ethical orientation, serving as both a cosmological anchor and a spiritual ideal within Buddhist soteriology.

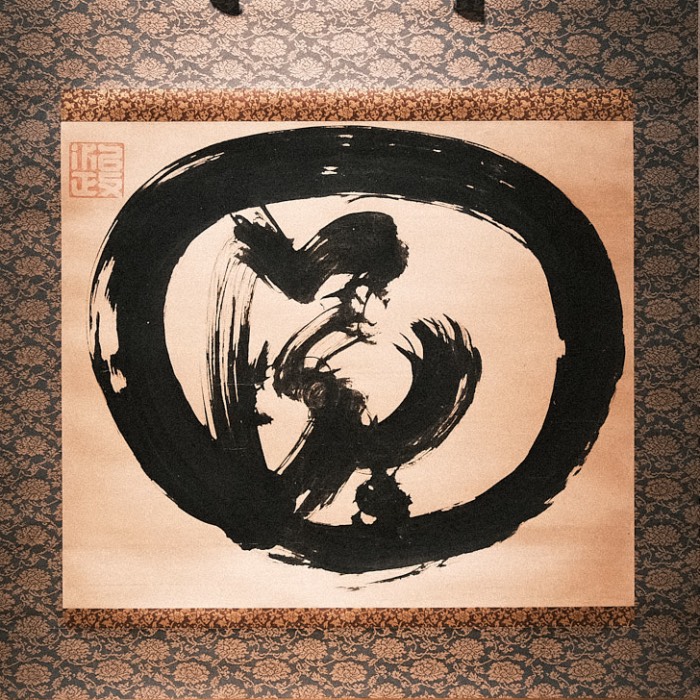

Buddhist mandala

A mandala (Sanskrit, “circle”) is a symbolic diagram used in Buddhist ritual, meditation, and visual culture, representing a sacred cosmos or spiritual universe. It serves both as a visual aid for meditative concentration and as a cosmological map of the enlightened mind.

Mandala of the six-armed goddess Jnanadakini, surrounded by eight emanations — representations of the devi that correspond to the colors of the mandala’s four directional quadrants, Tibet, late 14th century. Four additional protective goddesses sit within the gateways. Surrounding the mandala are concentric circles that contain lotus petals, vajras, flames, and the eight great burial grounds. Additional dakinis and lamas occupy roundels in the corners. The upper register depicts lamas and mahasiddhas representing the Sakya school’s spiritual lineage. The lower register depicts protective deities and a monk who performs a consecration ritual. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Mandalas have their origins in early Indian religious and cosmological traditions and were incorporated into Buddhist practice particularly in the Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions. In Buddhism, they often depict the universe centered around Mount Meru, encircled by continents, oceans, and celestial realms, embodying a vision of cosmic order and spiritual ascent.

Functions:

- Meditative aid: Used as a focus for samatha (calm abiding) and vipassanā (insight) practices.

- Ritual tool: Constructed during tantric initiations and visualized in deity yoga to symbolize the practitioner’s entry into a divine abode.

- Didactic image: Represents complex philosophical and metaphysical teachings, including the nature of emptiness (śūnyatā) and interdependence (pratītyasamutpāda).

A typical Buddhist mandala includes:

- Central deity or symbol (e.g., a Buddha or Bodhisattva)

- Four cardinal gates, often in a square palace or lotus design

- Concentric circles, representing the protective boundary of the cosmos

- Geometric symmetry, emphasizing order and balance

Traditions and variations:

- Tibetan Buddhism: Mandalas are elaborately constructed from colored sand (e.g., the Kālacakra Mandala) and ritually dismantled to express impermanence.

- Japanese esoteric Buddhism (Shingon): Features dual mandalas (Garbhadhātu and Vajradhātu) reflecting different aspects of the Buddha’s nature.

- Pure Land Buddhism: Sometimes uses mandalas to depict the Sukhāvatī (Pure Land of Amitābha Buddha).

Philosophical symbolism:

Beyond cosmology, mandalas symbolize the integration of the self, the path to enlightenment, and the non-dual nature of reality. The movement from the periphery to the center mirrors the practitioner’s journey toward realization.

The Ocean of Milk and its surroundings

Surrounding the central mountain of Meru and its accompanying continents lies the vast Ocean of Milk, a cosmic sea that plays a significant role in both Buddhist and broader Indian cosmologies. Far from being a mere embellishment, this ocean embodies layered symbolic meanings: it serves as a metaphysical boundary, a symbol of fluidity and impermanence, and a marker of the ungraspable nature of saṃsāric existence.

The Churning of the Ocean of Milk, ca. 1825. Depictions of the churning of the ocean are common in Indian art, often showing gods and demons working together to extract the nectar of immortality. This mythological event is not directly part of Buddhist cosmology but reflects the shared cultural heritage of South Asian religious traditions. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

In its Indian mythological roots, particularly within Vedic and later Hindu traditions, the Ocean of Milk is associated with the famous churning myth (samudra manthana), in which gods and demons churn the ocean to extract the nectar of immortality (amṛta). While Buddhism does not adopt this myth directly, it inherits the cosmological concept of a surrounding ocean as a liminal and generative force. This ocean is often described in Buddhist texts as separating the four great continents and defining the perimeter of the world system. Its role is less mythopoetic and more cosmographic: it sets a horizon beyond which lies only further layers of symbolic or protective mountains.

Buddhist reinterpretation of the Ocean of Milk emphasizes containment, separation, and the cyclical nature of existence. The ocean serves to contain the differentiated realms within a shared cosmological structure, symbolizing both the boundedness of conditioned existence and the fluid dynamics of rebirth and karmic motion. It is not a navigable body of water in the physical sense, but a mythic boundary that demarcates the limits of ordinary perception. Just as Mount Meru signifies stability and moral centrality, the cosmic ocean represents motion, dispersion, and the ceaseless currents of saṃsāra.

This interpretation aligns with the broader Buddhist cosmological view, where water often signifies both life and delusion, the medium through which beings drift, propelled by karma and ignorance. In ritual and meditative visualization, the Ocean of Milk is not just scenery but a cue to contemplate the boundless nature of saṃsāra and the necessity of finding firm ground through the Dharma. In this way, the ocean and mountain work in tandem: one encircles and diffuses, the other centers and elevates, together shaping a cosmos of moral consequence and contemplative significance.

Cosmology and karma

The classical structure of Buddhist cosmology is inseparable from the principle of karma. Spatial position, whether within a continent, above Mount Meru, or below in the infernal realms, is not random or fixed by divine will, but a direct expression of karmic conditions. The moral dimension of space becomes evident in the correlation between proximity to Mount Meru and one’s karmic standing. Celestial beings inhabit realms atop or above Meru, benefitting from the results of virtuous past actions. Human beings, situated on the continents at its base, are seen as ethically ambivalent but endowed with the rare opportunity for liberation. Below lie the ghost and hell realms, domains shaped by greed, hatred, and delusion.

This vertical stratification represents more than cosmological mapping; it is a spatial allegory for moral and psychological development. Rebirth into one realm or another is understood not only as a metaphysical transition but as a reflection of one’s inner state. The heavenly realms correspond to mental states of generosity, clarity, and equanimity; the lower realms to suffering born of confusion and harm. Thus, the cosmological system doubles as an ethical diagnostic, a chart of the mind’s karmic evolution.

Importantly, this structure is not static. Buddhist cosmology holds that all conditioned phenomena are impermanent, including the universe itself. The cosmos undergoes cycles of formation (vivarta), duration (sthiti), destruction (saṃvarta), and emptiness (śūnyatā), often over unfathomable expanses of time. These cosmic rhythms mirror the impermanence of individual existence and reinforce the urgency of the Buddhist path: even vast celestial orders are subject to dissolution. In this light, cosmology is not a stable map but a dynamic field — a vision of saṃsāra’s shifting architecture, within which beings endlessly rise and fall until awakening is realized.

Cosmological adaptation across cultures

As Buddhism spread across Asia, its cosmological frameworks were not merely transplanted but actively adapted and reinterpreted to align with diverse cultural, artistic, and doctrinal contexts. Central elements like Mount Meru and the surrounding Ocean of Milk remained significant, yet they took on new meanings depending on regional perspectives and religious priorities.

In Tibetan Buddhism, the cosmological vision centered around Mount Meru was deeply integrated into visual and ritual culture. Mandalas, intricate diagrams used for meditative visualization and initiation rituals, often depict Mount Meru at the center, surrounded by the continents, oceans, and celestial realms. These mandalas are not simply didactic representations of the universe but serve as contemplative tools that mirror the practitioner’s internal journey toward awakening. The vertical axis of Meru within these diagrams reinforces Vajrayāna’s focus on ascension through levels of consciousness and the union of cosmology with soteriological progression.

In East Asian traditions, particularly in China and Japan, the emphasis on Mount Meru and the four continents is present but often less central than in Tibetan contexts. East Asian cosmological maps and temple murals sometimes incorporate indigenous geomantic and Daoist elements, reflecting a fusion of Buddhist and local spatial ontologies. Rather than literal depictions of Meru, East Asian cosmologies often emphasize the Pure Lands or realms presided over by specific Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, reflecting devotional orientations that shift cosmological focus from structural geography to soteriological destinations.

In Theravāda contexts, cosmological themes appear prominently in temple art and narrative murals, especially in Southeast Asia. These murals often illustrate the vertical structure of existence — heavens, human world, and hells — with Mount Meru depicted at the center of a vast moral and cosmic order. These visual cycles are typically aligned with Jātaka tales and depictions of the Wheel of Life, embedding cosmological vision in ethical storytelling. In these traditions, the cosmos serves both as a backdrop and as an ethical reminder: one’s current condition reflects past actions and informs future possibilities.

Across these cultures, the adaptation of Buddhist cosmology reveals both continuity and creativity. While the foundational symbols remain, their articulation reflects the needs and insights of the communities that received and reinterpreted them. The enduring presence of Mount Meru and the Ocean of Milk across such diverse settings speaks to their flexibility as metaphors, capable of grounding highly varied expressions of Buddhist worldview, ethics, and meditative aspiration.

Modern reception and reassessment

In contemporary Buddhist discourse, the cosmological elements of Mount Meru and the Ocean of Milk present a challenge that has prompted diverse responses. A key tension lies between literalist and symbolic readings. Some traditionalist communities maintain a cosmologically realist view, treating these features as accurate depictions of the universe in accordance with scriptural authority. Others, particularly in modernist and reformist contexts, interpret them symbolically, as profound metaphors for spiritual principles, meditative experiences, or psychological states.

Modern scientific cosmology, with its heliocentric models and astrophysical accounts of space-time, directly contradicts the geocentric, stratified universe depicted in Buddhist cosmology. This contradiction has led to apologetic strategies aimed at reconciling the two: either by reinterpreting cosmological language as culturally contingent metaphor, or by asserting that spiritual and scientific cosmologies operate in distinct epistemic domains. In some circles, the abandonment of literal cosmology is viewed not as a loss of faith but as a recovery of Buddhism’s philosophical and experiential core.

At the same time, Mount Meru and the Ocean of Milk continue to resonate within psychological and ecological interpretations. In Buddhist-informed psychotherapy, the central mountain is sometimes read as a symbol of internal stability or awakening, while the encircling ocean represents the unconscious or the turbulent nature of conditioned existence. Ecological readings see Meru as a symbolic center of balance and interdependence, a metaphor for harmony within the web of life, and the ocean as a reminder of planetary interconnectedness and impermanence.

These modern reassessments reflect Buddhism’s long-standing capacity for adaptability. Rather than discarding cosmological elements as obsolete, many practitioners and scholars seek to reinterpret them in light of contemporary understanding — not as discarded relics of pre-scientific thought, but as dynamic symbols that continue to shape ethical imagination and spiritual practice in the modern world.

Conclusion

Mount Meru and the Ocean of Milk, while drawn from mythic and cosmological traditions, endure as potent symbolic frameworks within Buddhist thought and practice. Far from being static or obsolete relics of pre-scientific worldviews, they express the ethical and psychological architecture of saṃsāric existence and the path to its transcendence. These cosmological motifs map moral orientation onto space, transforming geography into a vehicle for insight. The towering axis of Meru reflects the vertical structure of ethical aspiration and karmic refinement, while the swirling ocean encircles it as a metaphor for the dynamic, unstable, and often bewildering nature of conditioned experience.

Across traditions and historical periods, these symbols have been reinterpreted, localized, and integrated into ritual, art, meditation, and ethical reflection. Their flexibility has enabled them to remain relevant across vastly different cultural landscapes, from Tibetan mandalas to Southeast Asian murals to modern psychological and ecological readings. In every context, they invite practitioners to contemplate the interplay between centrality and dispersion, stability and motion, ascent and return.

Ultimately, the significance of Mount Meru and the Ocean of Milk does not depend on their physical plausibility, but on their value as conceptual tools for ethical orientation and philosophical reflection. These cosmological motifs provide structured frameworks that help individuals and communities think about the nature of moral order, impermanence, and the dynamics of saṃsāra. Rather than offering a literal map of the universe, they function as symbolic references for interpreting human experience and guiding ethical practice within a Buddhist worldview.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments