The first modern encounters between the West and Buddhism: Colonialism, rediscovery, and reform

The 19th and 20th centuries marked the first sustained modern encounters1 between the Western colonial world and Buddhism. As European powers extended their empires across Asia, they encountered Buddhist traditions in vastly different historical conditions, from the diminished remnants in India to vibrant monastic cultures in Sri Lanka, Burma, and Southeast Asia. These encounters were not limited to military conquest or administrative control; they also unfolded through scholarship, missionary activity, education systems, and the appropriation of religious knowledge.

Parliament of the World’s Religions, Chicago, United States, 1893. The first major interreligious conference in the modern Western world, where Buddhist representatives participated and introduced Buddhism to Western audiences. The modern encounters between the West and Buddhism began at the end of the 19th century, with the rediscovery of Buddhism through colonial scholarship and archaeological excavations. While colonialism often suppressed indigenous agency, it also sparked a revival of interest in Buddhism, leading to the emergence of reform movements across Asia. The legacy of colonialism is thus one of deep entanglement: Buddhism was rediscovered, reformed, and globalized under the shadow of empire. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) (modified)

Colonialism both suppressed and exposed Buddhism. On the one hand, colonial regimes undermined Buddhist institutions through direct interference, economic marginalization, and ideological subjugation. On the other, they sparked new forms of academic interest and excavation that rediscovered lost or neglected Buddhist histories, especially in India, where Western Orientalist scholarship helped revive interest in a tradition long absent from the public religious landscape. Across colonized regions, Buddhist communities responded by defending, reinterpreting, and transforming their traditions, often aligning with modern ideas of rationalism, nationalism, and scientific inquiry while also resisting cultural imperialism.

In this post, we explore how colonial encounters reshaped Buddhism across Asia. Far from a neutral backdrop to reform, colonialism imposed destabilizing pressures that subordinated Buddhist institutions to imperial goals. Scholars and administrators often framed Buddhism through Western epistemologies, distorting its complexity while undermining local religious authority.

Buddhist reforms that emerged under these conditions were not simply spontaneous revivals but strategic adaptations shaped by unequal power dynamics. However, while colonial conditions imposed external pressures and limitations, Buddhist reformers across Asia responded with considerable creativity and resilience. They used the tools and discourses of the time, including print, education, and institutional reform, to reinterpret the Dharma in ways that were both faithful to core principles and responsive to new realities. The resulting forms of Buddhism were not merely diluted versions of a Western ideal but active, strategic adaptations that helped preserve, modernize, and globalize the tradition under challenging conditions.

The consequences and influences of colonialism on the (re)discovery of Buddhism: India as a case study

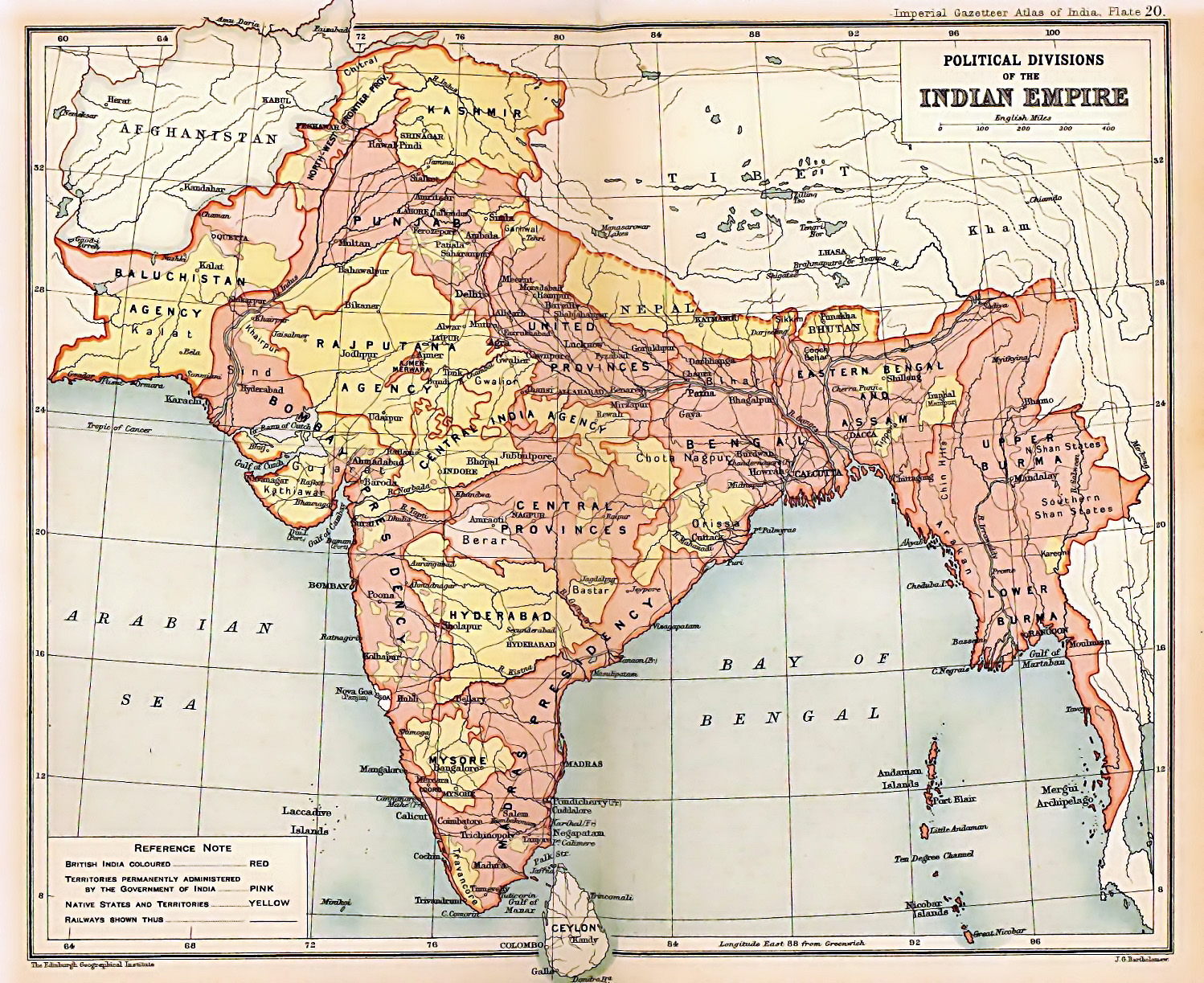

India serves as a particularly rich case study for understanding the complex dynamics of colonialism and Buddhism. The British colonial encounter with India was marked by a series of contradictions: while colonialism sought to suppress indigenous cultures, it also inadvertently facilitated the rediscovery and revival of Buddhism. This process unfolded through a combination of scholarly interest, archaeological excavations, and the emergence of reform movements that redefined Buddhism in modern terms.

The British Raj was the colonial rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent, lasting from 1858 to 1947. The map shows the political subdivisions of the British Raj in 1909. British India is shown in two shades of pink; Sikkim, Nepal, Bhutan, and the princely states are shown in yellow. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The colonial context: Dominance and contradiction

British colonial rule in India followed a long period of economic infiltration and strategic territorial acquisition, culminating in formal control under the British Crown in 1858. This colonization was achieved through a combination of military conquest, manipulation of local rulers, and the expansion of trade monopolies, most notably by the British East India Company. Once consolidated, colonial rule imposed a foreign administrative framework, prioritized resource extraction, and restructured local economies in ways that benefited the metropole while impoverishing Indian communities.

Culturally, the British justified their domination through ideologies of racial superiority, moral paternalism, and the so-called “civilizing mission.” These narratives masked the violence and exploitation intrinsic to colonial governance. Missionary activity, English-language education, and legal reforms were not neutral tools of progress but mechanisms for cultural control and ideological transformation. Traditional institutions, including religious ones, were often undermined or co-opted, reshaped to fit colonial priorities. The resulting system enforced deep structural inequalities and suppressed indigenous knowledge systems.

In this deeply unequal colonial context, India’s religious and philosophical heritage, long marginalized or forgotten, was suddenly subject to new forms of scholarly attention and reinterpretation which India’s religious and philosophical traditions were rediscovered, reinterpreted, and, often paradoxically, revived through colonial channels.

The state of Buddhism upon the arrival of the British Empire

By the time the British established dominance in India, Buddhism had long ceased to be a major religious presence on the subcontinent. Having gradually declined between the 8th and 13th centuries due to a combination of internal stagnation, absorption into Hindu devotional currents, and the destruction of key institutions (notably during Turkic invasions), Buddhism persisted in a diminished form, surviving through scattered communities, localized rituals, and certain cultural practices, especially in regions like Ladakh, the Himalayan belt, and among some lower-caste groups who retained traditions linked to the Buddha. However, its monastic institutions and philosophical schools had largely declined, and it was no longer a major force in public religious life across most of the subcontinent, especially in the Himalayan regions. The great monasteries of Nālandā and Vikramashila lay in ruins, and few Indians identified themselves as Buddhists.

Encounter and rediscovery: Colonial scholarship and Buddhist texts

Despite the exploitative nature of colonialism, British and European scholars played an important role in the recovery of India’s Buddhist past. Orientalists like James Prinsep, Alexander Cunningham, Eugène Burnouf, and T. W. Rhys Davids began deciphering inscriptions, translating texts, and cataloguing ruins. Their work was shaped by Enlightenment ideals and Protestant biases, which led them to idealize early Buddhism as a pure, rational, and philosophical system, i.e., one they claimed had later been ‘corrupted’ by ritualism, mythology, and local practices. While this framework helped establish the academic field of Buddhist Studies, it also imposed a Western evaluative lens onto non-Western traditions. The result was a reconfiguration of Buddhism that often sidelined its living expressions in favor of a reconstructed, text-based ideal aligned with colonial ideologies of decline and loss. This process not only reinforced the colonial narrative of India’s fallen past but also legitimized Western intellectual authority over the interpretation of Asian religions.

A spark in the West: Buddhist fascination in Europe

The publication of Pāli and Sanskrit Buddhist texts in the 19th century ignited widespread interest in Europe, where scholars, intellectuals, and spiritual seekers were increasingly disillusioned with institutional Christianity and on the lookout for alternative ethical and philosophical frameworks. Buddhism was interpreted as atheistic, rational, introspective, and psychologically profound, qualities that resonated with secular, scientific, and romantic ideals circulating in 19th-century Europe. Particularly in Germany, France, and Britain, Buddhism was eagerly taken up as both a fashionable object of exotic fascination and a serious source of philosophical inquiry.

However, this fascination often amounted to a one-sided and selective appropriation. Western interpreters tended to elevate what they perceived as the ‘original’ or ‘pure’ teachings of the Buddha, especially from early Pāli texts, while dismissing the rich liturgical, ritual, and devotional practices of contemporary Buddhist communities across Asia as corruptions or cultural baggage. This move echoed Protestant critiques of Catholicism and imposed a rationalist, text-centric, and anti-ritualist bias that reconfigured Buddhism in Western terms. In doing so, the West effectively created a new version of Buddhism that was more palatable to its own intellectual elite, often marginalizing the voices of Asian practitioners.

Moreover, this reimagined Buddhism frequently served to reinforce colonial and orientalist hierarchies. It enabled European scholars and readers to claim spiritual sophistication while maintaining a sense of civilizational superiority. Living Buddhisms, especially those practiced by colonized peoples, were often viewed as degraded or passive remnants of a once-great tradition. The philosophical virtues of the Buddha’s teaching were praised, but the social, cultural, and political agency of actual Buddhist societies was ignored or undermined.

Nonetheless, this wave of interest left a tangible mark on several major Western thinkers. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer was profoundly influenced by Buddhist concepts of suffering and renunciation, incorporating them into his philosophy of pessimism. Friedrich Nietzsche, while critical of Buddhism, engaged it as a serious foil to Western morality. In France, Renan and Émile Burnouf helped shape public perceptions of Buddhism through their comparative studies, albeit often laden with cultural prejudice. In Britain, scholars like T. W. Rhys Davids helped institutionalize Buddhist Studies, while spiritual seekers such as Theosophists Annie Besant and Henry Steel Olcott embraced Buddhism as a universal and rational religion.

Thus, while Western interest did contribute to global recognition of Buddhist philosophy, it also reflected and perpetuated the colonial dynamics of power and representation. The result was a Buddhism filtered through European modernity, both celebrated and distorted in the process.

Rediscovery and revival: The role of archaeology

Colonial-era archaeological excavations and surveys, driven by the imperial thirst for knowledge and classification, revealed monumental Buddhist heritage across India, from the ancient stūpas of Sanchi and Amaravati to the pilgrimage site of Bodh Gaya and the rock-cut caves of Ajanta. These findings, while framed as scientific and objective by colonial authorities, were deeply embedded in imperial ideologies of discovery and control. The very act of ‘rediscovering’ these sites suggested that India’s own people had forgotten their history, reinforcing the colonial narrative of cultural decline that only Western scholarship could reverse.

Yet these excavations had unanticipated consequences. As these monumental remains entered public awareness through reports, museums, and publications, they awakened Indian intellectuals and reformers to the richness of their own suppressed heritage. For many, the recovery of India’s Buddhist past became both a cultural and political act. Reformers, particularly from Sri Lanka and India, began to reinterpret this material legacy not as the property of archaeology but as a living foundation for moral, spiritual, and national renewal.

Anagarika Dharmapala saw in Bodh Gaya the desecrated yet redemptive heart of a once-glorious Buddhist civilization. His efforts to reclaim it were not merely devotional but strategically anti-colonial, aiming to restore a pan-Asian Buddhist identity rooted in India’s soil. Decades later, the most transformative figure in 20th-century Indian Buddhism, B. R. Ambedkar, drew from this historical rediscovery to articulate a radical new vision of the Dharma. Ambedkar, an anti-caste intellectual and principal architect of India’s constitution, led a mass conversion of Dalits to Buddhism in 1956 as a direct challenge to the caste hierarchy entrenched in Hinduism. He reinterpreted Buddhism as a rational, ethical, and socially liberatory tradition grounded in equality, dignity, and justice. His formulation, often called Navayāna or “New Vehicle” Buddhism, rejected metaphysical speculation and emphasized praxis, moral responsibility, and civic transformation. Navayāna remains a vital form of Engaged Buddhism in modern India and continues to inspire movements for social justice.

Thus, the colonial rediscovery of Buddhist sites, while driven by orientalist ambition, was subverted and reappropriated by Indian and South Asian actors. These monuments became stages of resistance, self-definition, and inter-Asian solidarity. Bodh Gaya in particular evolved from an archaeological curiosity into a crucible of political, religious, and symbolic struggle, embodying the tensions and aspirations of modern Buddhism in the age of empire.

Assessment: Violence, recovery, and irony

The British colonization of India played a contradictory role in the history of Buddhism. While colonialism suppressed indigenous agency and instrumentalized culture for imperial ends, it also unintentionally revived interest in India’s Buddhist past. The rediscovery of texts and sites helped catalyze reform movements, but it came at the cost of filtering Buddhism through Western norms. The irony lies in the fact that an empire built on domination helped rekindle a tradition rooted in liberation. Yet it was ultimately Indian Buddhists, through philosophical reinterpretation and political struggle, who reclaimed the Dharma on their own terms, both within India and globally. Although by the 19th century Buddhism had largely faded as a living tradition in India, colonial archaeologists and Orientalist scholars began unearthing its ancient heritage. Excavations at sites such as Sarnath, Nālandā, and Bodh Gaya, combined with translations of texts like the Dhammapada and the Milindapañha, awakened scholarly fascination in the West. This “scientific discovery” of Buddhism reframed it as a rational, ethical system distinct from the ritual-heavy forms of contemporary Hinduism and Christianity.

British and European scholars, often working with Indian collaborators, contributed to the formation of Buddhist Studies as an academic field. Figures such as T. W. Rhys Davids and Eugène Burnouf presented Buddhism as a historically significant, philosophically sophisticated tradition, often aligning it with Enlightenment values. These representations, however, were shaped by Western intellectual paradigms and carried implicit Protestant biases.

Paradoxically, Western colonial scholarship played a catalytic role in sparking Buddhist revival movements across Asia. Indian reformers and South Asian Buddhist leaders engaged with this academic rediscovery to reclaim and rearticulate their own heritage. Bodh Gaya became a transnational pilgrimage site and symbol of pan-Buddhist unity. Indian intellectuals, most notably B. R. Ambedkar, later drew on these revived sources to assert Buddhism as a path of liberation, dignity, and rationality, distinct from the oppressive structures of caste-based Hindu society.

In this way, the colonial encounter in India generated both the intellectual framework and the symbolic resources for a broader resurgence of Buddhism, one that was rooted in ancient texts and sites but articulated in modern, anti-colonial, and egalitarian terms. By the 19th century, Buddhism had largely disappeared as a living tradition from the Indian subcontinent, but its archaeological and textual remains were ‘rediscovered’ and studied extensively by British and European scholars. These studies contributed to a reimagining of India’s Buddhist past and stimulated interest among South and Southeast Asian Buddhists in reclaiming the Indian origins of their tradition. Sites like Bodh Gaya became symbols of transnational Buddhist revival, and Buddhist reformers from Sri Lanka, Burma, and beyond engaged with colonial-era scholarship to anchor their movements in the historical homeland of the Buddha.

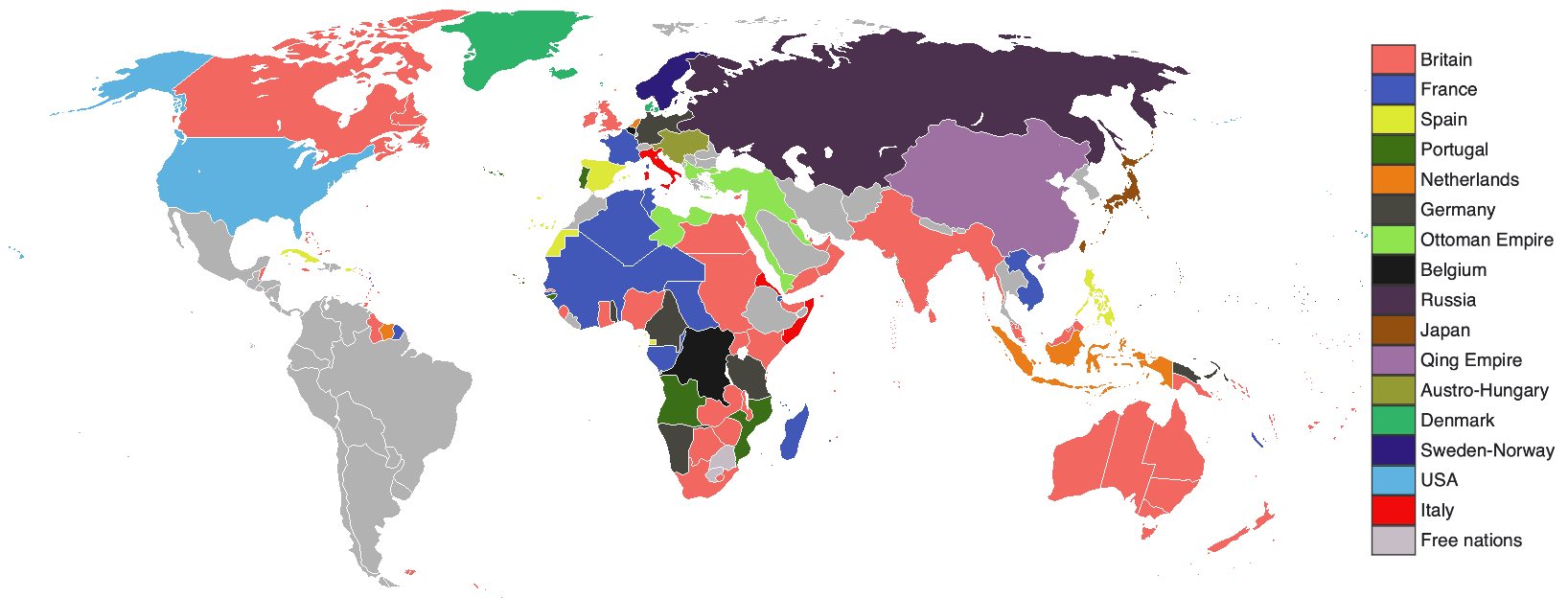

Colonial influence and exchange in other regions of Asia

The colonial encounter with Buddhism was not limited to India. Across Asia, colonial powers imposed their own structures of governance, education, and cultural representation, often marginalizing or distorting local religious practices. Yet these encounters also sparked significant transformations within Buddhist communities, leading to a complex interplay of suppression, adaptation, and revival.

Colonial empires 1898. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) (modified)

Colonial empires 1898. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) (modified)

British Ceylon (Sri Lanka)

Under British colonial rule, Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) experienced significant religious and cultural upheaval. The colonial administration, while officially neutral in religious affairs, heavily favored Christian missionary activity, especially through the control of education and public institutions. Christian missionary schools became widespread and often received financial and administrative support from the colonial government. Meanwhile, traditional Buddhist monastic education and temple patronage declined, and Buddhist institutions lost the legal and political privileges they had enjoyed under previous indigenous rule.

British Ceylon around 1914. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

British Ceylon around 1914. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

This period of institutional erosion was compounded by an ideological challenge. British Orientalist scholars and missionaries often portrayed Buddhism as a relic of the past, philosophically respectable in its early form, but later corrupted by superstition and ritual. These views were shaped by Protestant ideals of textual purity and moral reform, which filtered how Buddhism was studied, represented, and taught in colonial contexts. Buddhism in Sri Lanka was thus marginalized not only materially, but also discursively: it was either distorted to fit Western frameworks or dismissed as backward.

Yet this period also sowed the seeds of revival. Far from disappearing, Buddhism in Sri Lanka adapted and responded with resilience. The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a vibrant Buddhist revival movement, driven by lay activists, scholars, and reformist monks. Anagarika Dharmapala emerged as a central figure in this movement, advocating for a rational, text-based interpretation of Theravāda Buddhism that could stand on equal footing with Western religious and philosophical systems. He founded the Maha Bodhi Society, helped restore pilgrimage links with India, and challenged the dominance of Christian institutions through education, journalism, and public debate.

By the time Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948, Buddhism had not only survived colonial rule but had reasserted itself as a dominant force in national identity. Today, approximately 70% of Sri Lankans identify as Buddhists, and the country’s constitution affords Buddhism a special status. The colonial experience, therefore, did not lead to Christianization, but rather to a complex process of suppression, adaptation, and ultimately, reinvigoration of Buddhist life in Sri Lanka.

Burma (Myanmar)

The British annexation of Burma in the 19th century brought a dramatic rupture to the traditional political-religious structure of Burmese society. Under the Burmese kings, Buddhism had enjoyed state support, and the sangha (monastic community) was closely integrated with the monarchy, playing a central role in both spiritual and administrative life. With colonization, this alliance was dismantled: Buddhism was disestablished as a state religion, royal patronage ceased, and the sangha lost its institutional anchor, leading to fragmentation and decentralization.

A Japanese Map of British Burma in 1943. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

A Japanese Map of British Burma in 1943. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

In response to these disruptions, Burmese monks initiated reforms aimed at restoring doctrinal purity and maintaining communal cohesion. These included efforts to standardize monastic education, reaffirm adherence to the Vinaya (monastic code), and counter the influence of Christian missionary efforts. Lay support for these reforms was strong, as many Burmese people viewed Buddhism not only as a spiritual tradition but as a key marker of cultural identity.

As colonial rule deepened, Buddhism became increasingly intertwined with nationalist sentiment. Monks and lay leaders alike invoked Buddhist teachings and symbols as tools of resistance and resilience. Monasteries served as centers of education, political discussion, and cultural preservation. In movements such as the Saya San Rebellion (1930–1932), Buddhist imagery and rhetoric were used to challenge colonial authority and affirm Burmese sovereignty.

Thus, far from being weakened by colonial intervention, Burmese Buddhism transformed itself into a platform for religious renewal and national resistance. It retained its social centrality, adapted to the challenges of imperialism, and ultimately contributed to the shaping of modern Burmese identity.

French Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos)

In Indochina, French colonial policy generally relegated Buddhism to the cultural periphery, portraying it as a static and irrational tradition unsuited to modern governance or moral reform. French administrators privileged Catholic missionary work, built colonial educational institutions based on secular French models, and reduced the institutional power of Buddhist monastic orders. In doing so, they not only marginalized Buddhism as a living religious system but also disrupted its social and political functions within Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian communities.

French Indochina around 1933. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

French Indochina around 1933. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Nevertheless, Buddhist leaders and communities in Indochina proved far from passive. Especially in Vietnam, Mahāyāna intellectuals and monks began to mobilize Buddhism as a tool of national self-definition. They creatively blended Confucian ethics, Buddhist moral teachings, and Western political ideas such as self-determination and cultural sovereignty to oppose both colonial domination and emerging forms of ideological dogmatism. Figures such as Thích Quảng Đức, whose self-immolation in 1963 would later become iconic, reflected a lineage of Engaged Buddhism rooted in resistance.

In Cambodia, Theravāda Buddhism remained central to the cultural identity of the Khmer people, even under colonial oversight. Monks participated in educational reform, preserved traditional knowledge, and offered subtle critiques of colonial structures. In both Vietnam and Cambodia, Buddhist institutions adapted to modern forms of activism while maintaining continuity with their doctrinal heritage.

Thus, despite efforts to marginalize or instrumentalize it, Buddhism in French Indochina evolved as a resilient and dynamic force. It provided ethical grounding, cultural continuity, and a vocabulary of resistance for nationalist movements, contributing significantly to the broader struggle for decolonization and postcolonial identity.

Japan

Although Japan was never colonized, it was profoundly shaped by the threat and pressure of Western imperialism in the 19th century. Following the arrival of Commodore Perry’s fleet in 1853 and the forced opening of Japan to Western trade, the Meiji government embarked on a radical program of modernization and nation-building. As part of this effort, the state promoted Shinto as a national ideology and sought to subordinate Buddhism to state control, viewing it as feudal, foreign-influenced, and ideologically incompatible with the goals of a centralized modern nation-state.

Commodore Matthew Perry’s “Black Ship”, watercolor on paper, between 1860 and 1900, unknown artist. The arrival of Perry’s fleet in 1853 forced Japan to open its ports to Western trade, leading to the Meiji Restoration and a period of rapid modernization. This encounter with the West profoundly influenced Japanese Buddhism, prompting both reform and adaptation in response to colonial pressures. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Commodore Matthew Perry’s “Black Ship”, watercolor on paper, between 1860 and 1900, unknown artist. The arrival of Perry’s fleet in 1853 forced Japan to open its ports to Western trade, leading to the Meiji Restoration and a period of rapid modernization. This encounter with the West profoundly influenced Japanese Buddhism, prompting both reform and adaptation in response to colonial pressures. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The result was the haibutsu kishaku (“abolish Buddhism and destroy Śākyamuni”) movement, during which thousands of Buddhist temples were closed, monks were defrocked, and temple lands were seized. In response, the Buddhist establishment adapted by aligning itself with the new values of the state, emphasizing moral education, social responsibility, and loyalty to the emperor. Lay movements grew, and Buddhist thinkers developed new interpretations of doctrine that presented Buddhism as rational, ethical, and in harmony with science and progress.

By the early 20th century, Zen in particular had been reformulated as a distinctly Japanese spiritual tradition that, in some nationalistic interpretations, was loosely associated with bushidō (the way of the warrior) and national character, though historically, Zen and bushidō were distinct traditions with only selective ideological overlaps. Zen, focusing in its essence on personal discipline, intuitive insight, and spiritual independence, was later exported to the West, where it gained popularity as a philosophy of mind and meditation. One of the most influential figures in this global transmission was Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, who reinterpreted Zen Buddhism as a universal, experiential philosophy stripped of its ritualistic and metaphysical layers. Writing in English and addressing Western audiences, Suzuki emphasized the compatibility of Zen with modern psychology, individualism, and introspective practice.

Suzuki’s portrayal of Zen resonated deeply with spiritual seekers and intellectuals in Europe and North America, who were drawn to what appeared to be a non-dogmatic, experience-based path to insight. This transformation helped Zen gain tremendous popularity globally, particularly in the postwar period. However, it often came at the expense of the tradition’s historical complexity, social embeddedness, and liturgical dimensions.

Thus, Japan’s modern Buddhist reforms, especially in the case of Zen, were shaped by internal pressures to modernize and external pressures to resist colonization. Figures like Suzuki bridged these dynamics, producing a version of Buddhism that was both authentically Japanese and globally consumable, leaving a legacy of ideological reinvention and cultural export that continues to influence perceptions of Buddhism worldwide.

Thai Buddhist reforms

King Mongkut (Rama IV), who reigned from 1851 to 1868, was a monk for over two decades before ascending the throne. During his time in the monastic order, he became acutely aware of lax practices and inconsistencies within the Thai sangha. Influenced by both traditional Pāli scholarship and his exposure to Western scientific and rationalist thought through interactions with missionaries and diplomats, Mongkut sought to purify and modernize Thai Buddhism from within. Although Thailand (then Siam) was never colonized, Mongkut was deeply aware of the colonial threat posed by European powers surrounding the region, and his reforms can also be understood as a proactive effort to strengthen the state’s sovereignty and cultural legitimacy in a colonial world.

He initiated a reform movement that culminated in the founding of the Thammayut Nikāya (“Reform Sect”) in 1833, even before his kingship. This new monastic order emphasized stricter adherence to the Vinaya (monastic code), greater textual engagement with the Pāli Canon, and the elimination of syncretic rituals and folk practices deemed unorthodox. As king, he institutionalized these reforms at a national level, using his royal authority to promote a disciplined, centralized, and scripturally grounded form of Theravāda Buddhism.

Mongkut’s reforms reflected Enlightenment ideals such as rationalism, empiricism, and order, and they laid the groundwork for later waves of Buddhist modernism across Southeast Asia. Crucially, they also served as a strategic response to the geopolitical pressures of the time. Surrounded by colonized neighbors, British Burma to the west and French Indochina to the east, Mongkut was acutely aware of the threat posed by European imperial powers. His modernization of Buddhism, alongside other state reforms, helped present Siam as a ‘civilized’ and sovereign nation in the eyes of the West, thereby strengthening its diplomatic position and contributing to its ability to remain independent in an era of widespread colonization. His legacy is not only one of doctrinal purification but also of cultural negotiation: adapting Buddhism to a rapidly changing world without surrendering its core values.

Tibetan responses to modernity

Although Tibet was not formally colonized by Western powers, the Chinese invasion in 1959 and the subsequent exile of the Tibetan government and religious leadership initiated a profound period of upheaval and transformation. The forced displacement of the Tibetan monastic community, especially the 14th Dalai Lama and his closest circle, created both a rupture with traditional structures and an opportunity for global engagement.

Emblem of Tibet, used by the Tibetan Government in Exile. The Emblem depicts a moon and sun over the Himalayas, two Tibetan snow lions supporting the eight fold dharmacakra and the red and pink ribbon below reads: “bod gzhung dga’ ldan pho brang phyogs les rnam rgyal” or “Tibetan Government, Garden Palace, victorious in all directions”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Emblem of Tibet, used by the Tibetan Government in Exile. The Emblem depicts a moon and sun over the Himalayas, two Tibetan snow lions supporting the eight fold dharmacakra and the red and pink ribbon below reads: “bod gzhung dga’ ldan pho brang phyogs les rnam rgyal” or “Tibetan Government, Garden Palace, victorious in all directions”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

In exile, Tibetan leaders worked not only to preserve their religious and cultural heritage but also to translate its core values into a language accessible to international audiences. The 14th Dalai Lama, in particular, became a charismatic global figure who emphasized compassion, nonviolence, and secular ethics. He promoted dialogue between Buddhism and modern science, especially in the fields of psychology and neuroscience, framing Tibetan Buddhism as both ancient and adaptable.

This rearticulation was more than survival strategy. It was also a conscious act of spiritual diplomacy. Tibetan Buddhism came to be perceived in the West as a deeply humane, meditative, and non-dogmatic tradition. Monastic institutions were re-established in India and Nepal, while Tibetan teachers began founding centers across Europe, North America, and beyond. In this process, Tibetan Buddhism evolved into a transnational religious movement, shaped by exile but oriented toward global relevance.

Colonialism and Buddhism

Colonialism played a central and ambivalent role in shaping the trajectory of modern Buddhism. While often destructive and dehumanizing, the colonial encounter paradoxically catalyzed both the scholarly rediscovery of Buddhism and the rise of reformist movements within Buddhist societies. These reforms were not purely endogenous renewals of spiritual life, but responses shaped by asymmetries of power, forced cultural encounters, and the epistemic structures imposed by imperial rule.

European colonial administrators, missionaries, and Orientalist scholars commonly portrayed Buddhism, like other non-Christian religions, as static, irrational, and degenerate. This served both to justify colonial domination and to open space for missionary activity and cultural reengineering. However, in their attempt to catalogue and control, colonial powers also invested in the excavation of Buddhist sites, translation of canonical texts, and the academic study of Buddhist philosophy. These activities, though embedded in imperial ideologies, inadvertently laid the foundations for Buddhist Studies and reignited global interest in the Dharma.

Yet the form of Buddhism that emerged through these channels was often shaped more by European expectations than by Asian realities. Reformist Buddhists, seeking legitimacy in a colonial world, increasingly aligned their teachings with Western ideals: rationality, moral universalism, and scientific compatibility. In doing so, they emphasized canonical texts over living practices, marginalized ritual and devotion, and redefined Buddhism as a religion of ethical reason. This mirrored Protestant models of religion and responded to the political need for a cultural identity that could resist colonial stereotypes while appealing to modern sensibilities.

In many cases, colonialism also enabled the rise of nationalist Buddhism. Monks and lay leaders used the Dharma as a source of cultural sovereignty, resistance, and mobilization, particularly in Sri Lanka, Burma, and Vietnam. But this alignment of Buddhism with modern nation-building also introduced new tensions, as Buddhist symbols were incorporated into exclusivist or ethnocentric ideologies.

These dynamics produced a Buddhism that was at once revitalized and transformed, globally visible, intellectually respected, and politically mobilized, but also filtered through foreign epistemologies and elite institutions. The legacy of colonialism is thus not merely one of disruption or destruction, but of deep entanglement: Buddhism was rediscovered, reformed, and globalized under the shadow of empire.

Buddhism on the World Stage: The 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions

A critical turning point in the global awareness of Buddhism occurred at the end of the 19th century, when Buddhist representatives participated in the 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. This was the first major interreligious conference in the modern Western world and marked a historic moment for the public introduction of Buddhism to Western audiences, outside the narrow circles of Orientalist scholarship or colonial administration.

The Parliament, held as part of the World’s Columbian Exposition, was organized primarily by liberal Protestant thinkers seeking to present religion as a universal and unifying human concern. In this context, several Buddhist delegates were invited from Asia, most notably Anagarika Dharmapala from Ceylon (Sri Lanka), a lay Theravāda reformer associated with the Buddhist revival movement. Dharmapala’s eloquent presentation of Buddhism as a rational, ethical, and scientifically aligned worldview resonated with the Parliament’s progressive and comparative aims. His appearance left a deep impression on the American audience and media.

Other Buddhist figures from Japan, Thailand, and Burma also attended or were represented indirectly, but it was particularly the voices of reform-minded Buddhists such as Dharmapala that shaped early Western impressions. These presentations reframed Buddhism not as a mystical or superstitious tradition, as had often been suggested in colonial discourse, but as a coherent, moral, and intellectually respectable alternative to Christianity.

The Parliament of 1893 thus functioned as a crucial arena for the self-representation of Asian religious traditions on Western terms, while simultaneously challenging dominant colonial narratives that depicted non-Western religions as inferior. The event catalyzed the formation of early Buddhist societies in the United States and laid the groundwork for the 20th-century development of Western Buddhism. It also reinforced emerging transnational reform movements in Asia by demonstrating the global resonance of Buddhist modernism.

In this sense, the Parliament represents not only a historical moment of “first contact” between Buddhism and a broader Western public, but also a strategic deployment of religious identity by Asian intellectuals navigating both colonial subjugation and modern global networks.

Conclusion

The 19th and 20th centuries marked a critical turning point in the history of Buddhism, shaped not by internal doctrinal change alone but by complex and often coercive interactions with colonial powers. While colonialism destabilized Buddhist institutions across Asia, through missionary encroachment, economic marginalization, and epistemic domination, it also triggered processes of rediscovery, academic study, and self-reform. In particular, the colonial encounter in India reawakened interest in a long-dormant tradition, both within South Asia and among Western scholars.

The Buddhist responses to these pressures were diverse. Reform movements emerged that sought to defend Buddhism against Christian proselytization, reinterpret its doctrines to fit scientific and ethical modernity, and reassert its relevance in national identity formation. These movements were never purely reactive; they often entailed deliberate and creative adaptation, from the rationalist Buddhism of Anagarika Dharmapala and B. R. Ambedkar, to the internationalist efforts of Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki and the Dalai Lama. In other regions, such as Burma, Thailand, and Vietnam, Buddhism served as a platform for anti-colonial resistance and cultural renewal.

Yet these transformations came at a cost. Buddhism as redefined under colonial modernity often prioritized textual study, moral philosophy, and psychological introspection, frequently echoing Protestant and Enlightenment ideals. Ritual, devotional practices, and local cosmologies were sidelined or discarded as “superstitions”, leading to a version of Buddhism more acceptable to Western intellectual audiences but less reflective of its full historical and cultural complexity.

The culmination of these intersecting trajectories of colonial domination, scholarly rediscovery, and indigenous reform found one of its most symbolic expressions at the 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. For the first time, representatives of living Buddhist traditions such as Anagarika Dharmapala from Ceylon and Zen delegates from Japan, spoke directly to a Western audience not as subjects of study, but as articulate proponents of a rational and ethical world religion. This event marked a crucial shift: Buddhism was no longer a passive object of European inquiry or a tradition in decline, but a global religion capable of modern self-representation. It laid the foundations for what would become the Western perception of “modern Buddhism”: transnational, reform-minded, and resonant with scientific rationalism and ethical universalism. In this way, the Parliament served as both a consequence of colonial processes and a platform that exceeded their frame, opening the path for a truly global Buddhist modernity.

Understanding this entangled history is essential. Modern global Buddhism cannot be separated from the legacy of colonial encounters. It was through these encounters that Buddhism was not only challenged and marginalized but also revitalized, internationalized, and reframed. The result is a Buddhist modernity that continues to grapple with inherited tensions: between East and West, tradition and innovation, spiritual depth and cultural politics.

References and further reading

- Almond, Philip C., The British Discovery of Buddhism, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521033855

- Bechert, Heinz (ed.), When Did the Buddha Live? The Controversy on the Dating of the Historical Buddha, 1996, Sri Satguru Publications, ISBN: 978-8170304692

- Gombrich, Richard, Theravāda Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo, 2006, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415365093

- Lopez, Donald S., Curators of the Buddha: The Study of Buddhism under Colonialism, 1995, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226493091

- Queen, Christopher S. and Sallie B. King (eds.), Engaged Buddhism: Buddhist Liberation Movements in Asia, 1996, SUNY Press, ISBN: 978-0791428443

- Skilton, Andrew, A Concise History of Buddhism, 1997, Windhorse Publications, ISBN: 978-0904766929

- Snodgrass, Judith, Presenting Japanese Buddhism to the West: Orientalism, Occidentalism, and the Columbian Exposition, 2003, University of North Carolina Press, ISBN: 978-0807827857

comments