Meditation as the liberation from suffering

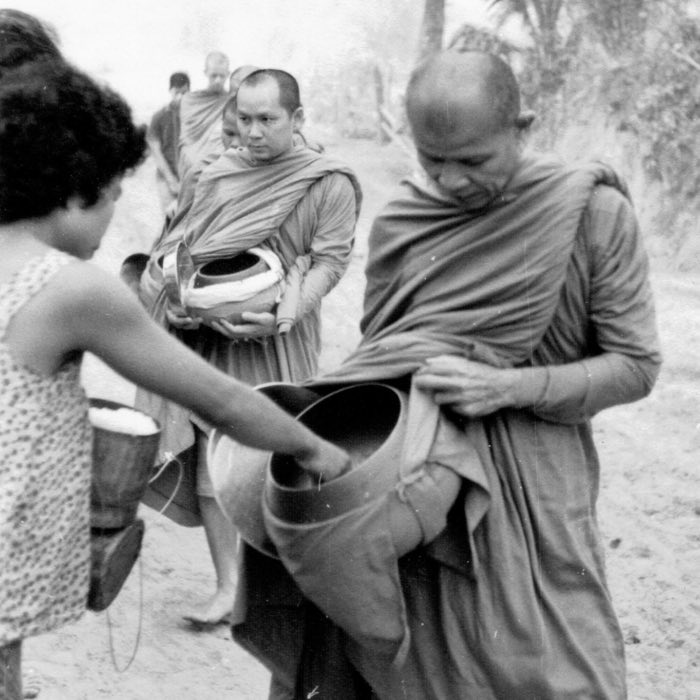

In the Buddhist tradition, meditation is not an isolated technique but the living heart of the path to liberation. It embodies the experiential core of the samādhi section of the Noble Eightfold Path — comprising right effort, right mindfulness (sati), and right concentration (samādhi) — and serves as the necessary foundation for the development of liberating insight (vipassanā).

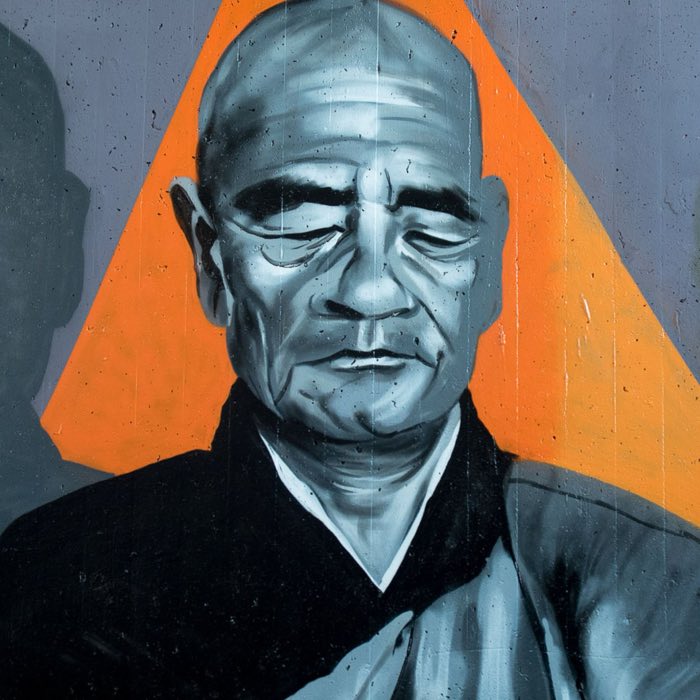

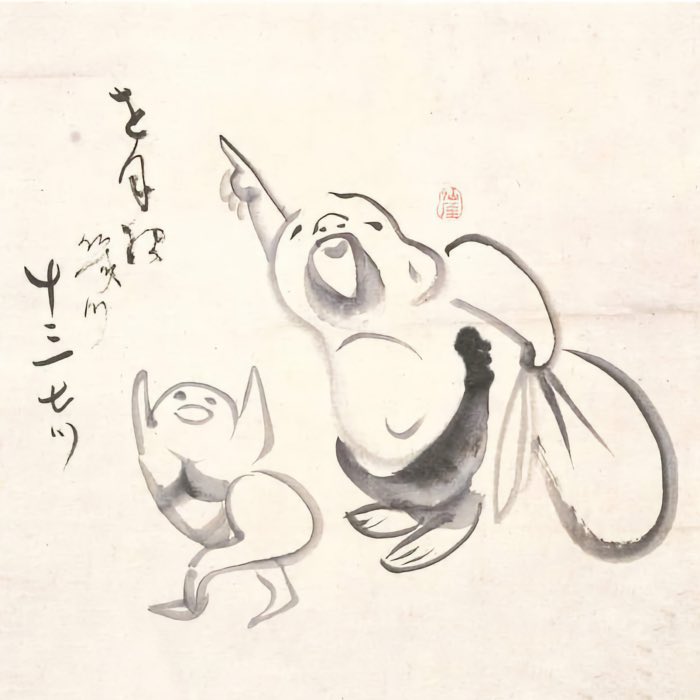

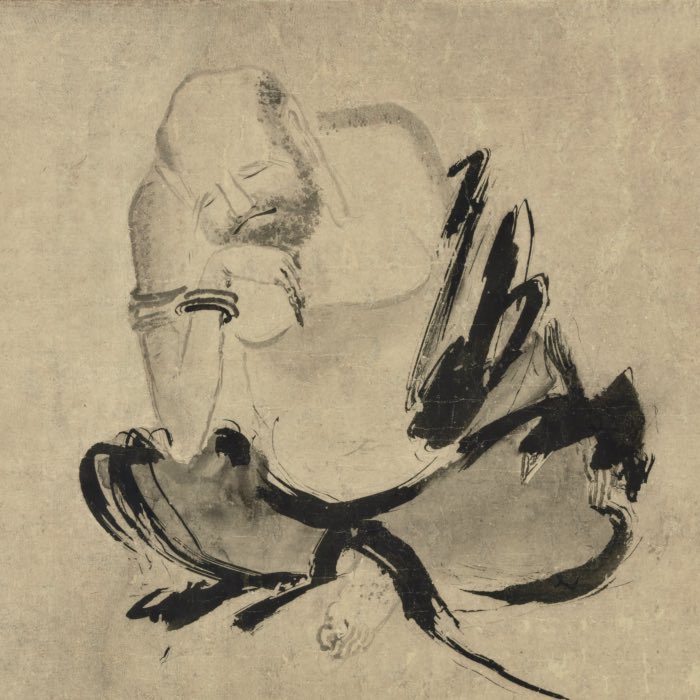

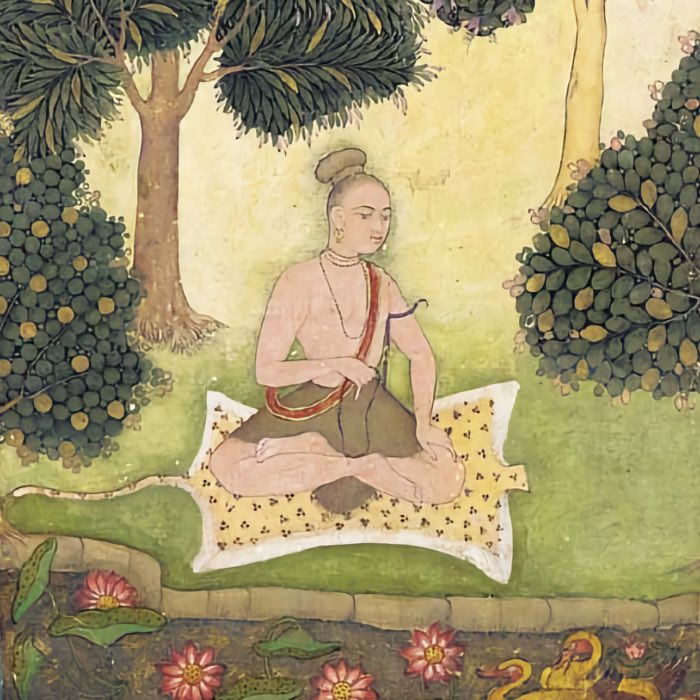

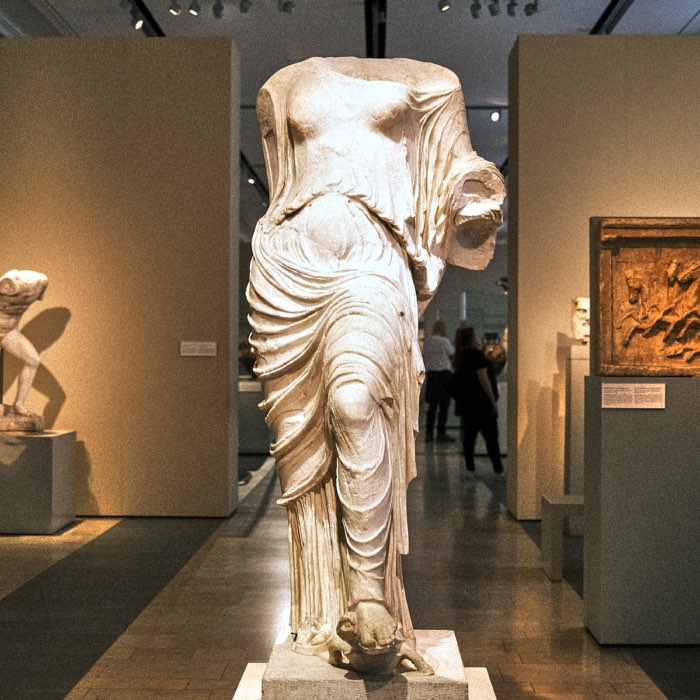

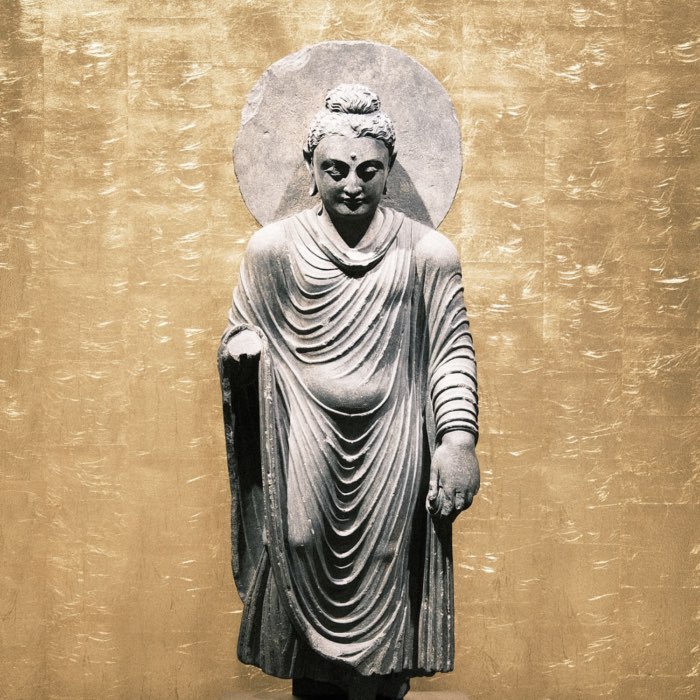

Māra’s assault, Gandhāra, present-day Pakistan, 2nd–3rd century CE, schist relief. The figure of Siddhartha Gautama is depicted seated in meditation beneath the Tree of Awakening. While engaged in concentrated observation — traditionally interpreted as mindfulness of breathing — he is confronted by wild, chaotic figures representing the forces of Māra. Māra, in early Buddhist symbolism, personifies the psychological and existential entanglements that sustain suffering (dukkha), including fear, desire, aggression, and distraction. Yet Siddhartha remains unmoved, illustrating the meditative equanimity that, according to early texts, enables liberation from these forces. Exhibited at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, 2023.

Māra’s assault, Gandhāra, present-day Pakistan, 2nd–3rd century CE, schist relief. The figure of Siddhartha Gautama is depicted seated in meditation beneath the Tree of Awakening. While engaged in concentrated observation — traditionally interpreted as mindfulness of breathing — he is confronted by wild, chaotic figures representing the forces of Māra. Māra, in early Buddhist symbolism, personifies the psychological and existential entanglements that sustain suffering (dukkha), including fear, desire, aggression, and distraction. Yet Siddhartha remains unmoved, illustrating the meditative equanimity that, according to early texts, enables liberation from these forces. Exhibited at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, 2023.

The task of Buddhist meditation is not merely to calm the mind but to transform the entire way we experience and respond to reality. This transformation unfolds through the interplay of two inseparable dimensions: calming meditation (samatha), which stabilizes attention and fosters inner stillness; and insight meditation (vipassanā), which investigates the impermanent, unsatisfactory, and selfless nature of all experience. Meditation is thus the bridge between Buddhist philosophy and lived understanding — where abstract teachings become concrete and embodied.

In this post, we approach meditation not simply as a spiritual or psychological tool, but as a method for liberating the mind from its conditioned patterns. We explore how it addresses the fragmented nature of untrained consciousness, how it refines attention through deepening stages of absorption (jhāna), and how it opens the way to [ethical transformation and wisdom. Meditation here is not just a practice — it is a reorientation of the entire self toward clarity, compassion, and freedom. In this post, we approach meditation not simply as a spiritual or psychological tool, but as a method for liberating the mind from its conditioned patterns. We explore how it addresses the fragmented nature of untrained consciousness, how it refines attention through deepening stages of absorption (jhāna), and how it opens the way to [ethical transformation and wisdom. Meditation here is not just a practice — it is a reorientation of the entire self toward clarity, compassion, and freedom.

The natural state of the untrained mind

Buddhist analysis of the mind begins with a fundamental observation: left untrained, the mind is neither stable nor free. It is shaped by two predominant tendencies: restlessness and inertia. In this natural, untrained state, the mind oscillates between agitation and sluggishness, rarely maintaining clarity or continuity of attention.

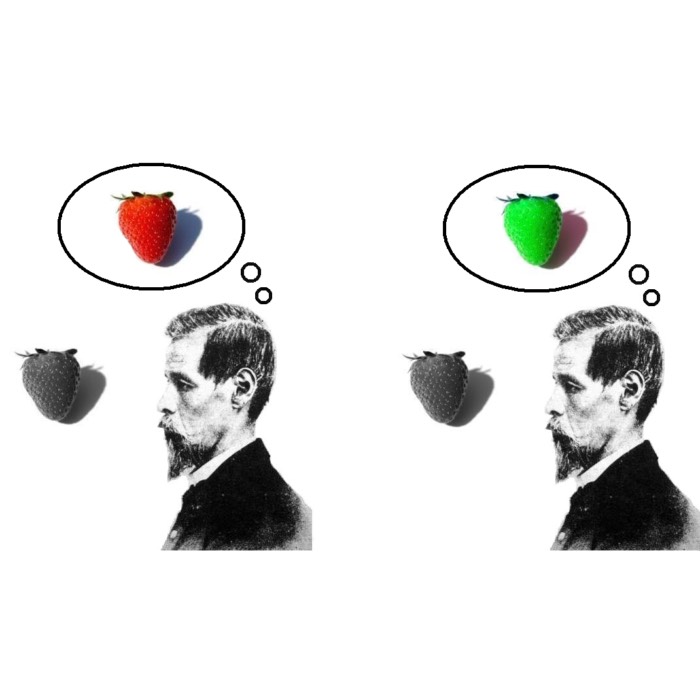

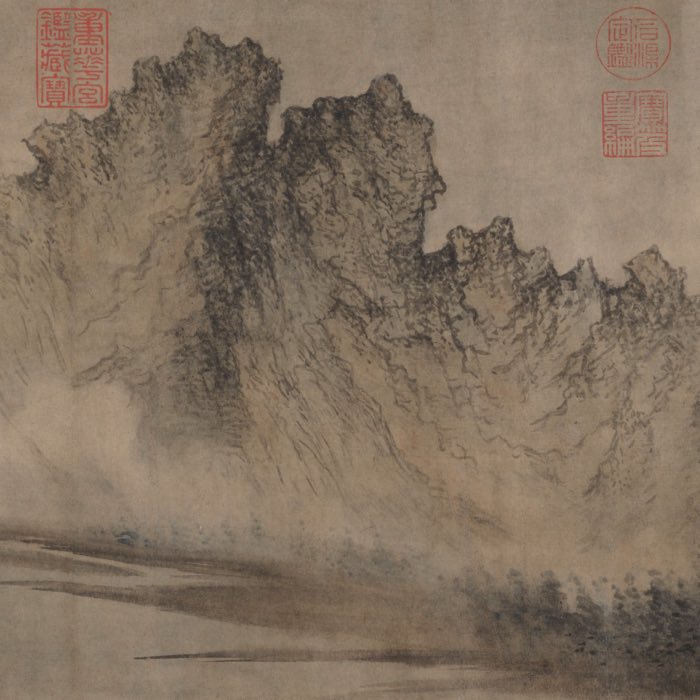

Restlessness appears as an incessant drifting of attention from one object to another, propelled by fleeting sensations, desires, and aversions. Early Buddhist texts offer vivid analogies for this condition. One compares the mind to a monkey swinging restlessly from branch to branch, never pausing, always grasping for the next support. Another likens it to a fish flailing chaotically on dry land, desperately seeking new footholds. These images highlight how attention, in its natural state, lacks stability and continuously reacts to fleeting stimuli. Thoughts and emotions arise unpredictably, often succeeding each other rapidly, driven by the habitual search for pleasure and the avoidance of discomfort. This instability is so deeply embedded that it usually remains unnoticed unless deliberate observation is undertaken.

A simple example can illustrate this phenomenon: imagine sitting down at your desk to begin work on a task. As you open your notebook, your mind briefly flashes to an unrelated email you forgot to answer. This leads you to think about an upcoming meeting, which reminds you of a colleague you need to call, which in turn triggers a memory of a conversation you had last week. Within moments, your mind has drifted far from your original focus, with each new thought arising almost automatically. This uncontrolled chain reaction mirrors the chaotic and fragmented operation of the untrained mind.

Alongside this mental turbulence stands inertia — the mind’s passive clinging to familiar and habitual patterns of thought and reaction. Rather than striving toward clarity or fresh understanding, the untrained mind tends to circle within well-worn loops of craving (tanhā), aversion (dosa), and confusion. When attention is not deliberately directed, it defaults to following familiar pathways, reproducing the same evaluations, emotional reactions, and behaviors as before. In practical terms, this inertia manifests as a tendency to ruminate on worries, replay grievances, or indulge in habitual daydreaming, even when such activities offer no real satisfaction. Over time, this repetitive circulation reinforces the mental habits that sustain suffering, leaving little room for intentional change or genuine insight.

When practitioners attempt to interrupt this natural chaos through meditation, they often encounter what Buddhist traditions identify as the Five Hindrances (nīvaraṇa). These obstacles are psychological tendencies that arise to block the development of mental stability and clarity:

- Sensory desire (kāmacchanda): A craving for pleasant experiences or distractions. As soon as focus is attempted, the mind seeks stimulation elsewhere — for instance, by suddenly remembering an appetizing meal, feeling an urge to check social media, or daydreaming about pleasurable experiences. This restlessness reflects the mind’s habitual search for immediate gratification.

- Ill-will (vyāpāda): Feelings of irritation, resentment, or anger that arise when reality does not align with one’s preferences. During concentration attempts, small inconveniences — such as background noise, an uncomfortable chair, or even one’s own restless mind — may provoke disproportionate frustration, distracting and destabilizing attention.

- Sloth and torpor (thīna-middha): A state of dullness and inertia affecting both the body and mind. When this hindrance is present, maintaining focus feels unusually difficult — the body may feel heavy and lethargic, while the mind sinks into a murky, clouded state lacking energy or clarity. Even simple efforts toward concentration seem disproportionately exhausting, making it tempting to give up or drift into daydreaming. Although physical tiredness might sometimes be involved, the deeper issue is a mental unwillingness to engage with the effort required for sustained awareness.

- Restlessness and remorse (uddhacca-kukkucca): A mental agitation that manifests either as excitement over achievements or as anxiety over perceived failures. Instead of resting steadily on the object of meditation, the mind flits between self-congratulation, worry, or replaying past events, all of which disturb concentration and destabilize calm observation.

- Skeptical doubt (vicikicchā): Distrust in the value, purpose, or efficacy of meditation itself. When this hindrance arises, the mind becomes caught in questioning whether the practice is worthwhile, whether one is capable of success, or whether the teachings themselves are reliable. Such doubt disperses energy and breaks the continuity of practice.

These hindrances are not abstract ideas; they are immediate and recognizable features of the mind’s natural resistance to discipline. Each represents a habitual response pattern that reinforces untrained reactivity. Recognizing and skillfully working with these hindrances is a core aspect of Buddhist meditation practice, and overcoming them is essential for cultivating true mental freedom.

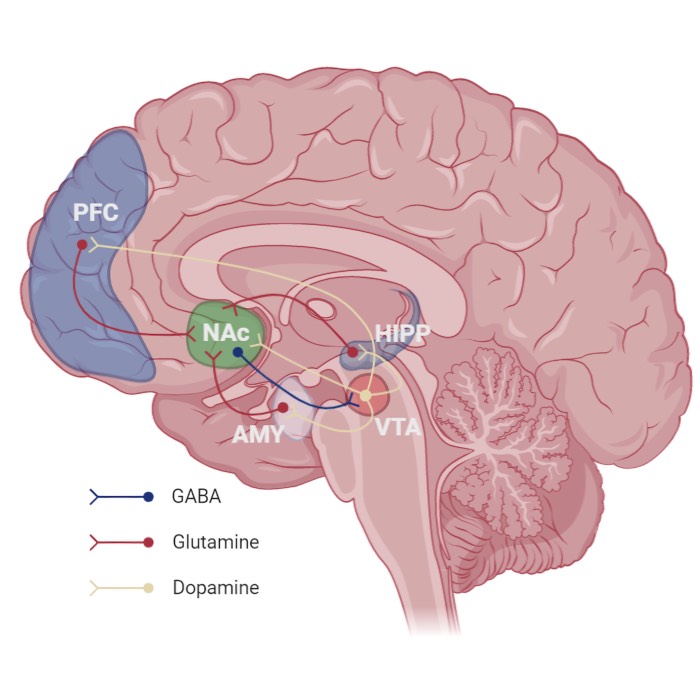

Importantly, this natural condition of the untrained mind is not neutral: it actively perpetuates suffering. This is because the untrained mind automatically reacts to each sensation — whether pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral — by generating craving, aversion, or boredom. These reactions reinforce habitual patterns of clinging and resistance, which in turn sustain dissatisfaction and restlessness. In this way, the mind’s own unconscious responses trap it in a self-perpetuating cycle of suffering. Every fleeting sensation, automatically evaluated through vedanā (feeling-tone), becomes a site where craving or aversion can arise. Without deliberate training, attention remains fragmented and reactive, fueling the endless cycle of dissatisfaction described in the core Buddhist concepts of impermanence (anicca), unsatisfactoriness (dukkha), and non-self (anattā).

Thus, training the mind via meditation is not an optional refinement but a necessary practice. It offers a method to break the unconscious momentum of the mind, to establish clarity, and to create the inner conditions for true freedom, as we will explore in greater detail in the next section.

Meditation as a bridge between theory and practice

Given the mind’s natural instability and its tendency to perpetuate suffering through unconscious reactions, the question arises: how can one effectively intervene in this process? Buddhist philosophy offers a clear answer: through meditation. Meditation is not an end in itself, but a transformative practice aimed at reshaping character, altering perception, and ultimately ending suffering. It emphasizes the direct, experiential realization of core insights — not merely their intellectual acceptance. Meditation occupies the critical middle ground between theoretical understanding and lived transformation. It serves not simply as a method for calming the mind, but as an instrument for unveiling and systematically dismantling the reactive mechanisms that fuel suffering.

Just as learning to master a complex physical skill, such as learning a new language or refining athletic performance, requires both theoretical understanding (grammar rules, movement techniques) and relentless, practical application (speaking practice, repeated drills, correction), the path to liberation requires a dual engagement: grasping the principles of impermanence, suffering, and non-self, and training the mind through meditation to directly perceive these truths in moment-to-moment experience.

To illustrate this transformative effect, consider a simple meditation exercise. Imagine sitting quietly and directing your full attention to the sensation of your breathing. Almost immediately, thoughts arise: plans for later, worries about unfinished tasks, fragments of past conversations. Instead of being swept along by each emerging thought, you gently acknowledge them without reacting and return your attention to the breath. Each moment of noticing and redirecting represents a subtle act of freeing the mind from its habitual reactivity. Over time, these small acts accumulate into a more stable, clear, and autonomous mental state, no longer dominated by unconscious impulses.

Meditation is thus a laboratory where practitioners investigate how craving arises, how aversion manifests, and how attachment solidifies around fleeting sensations and thoughts. Through this disciplined observation, meditators begin to emancipate themselves from the unconscious pull of their own mental habits. Importantly, this process is neither purely cognitive nor purely emotional — it involves a gradual transformation of the entire way experience is structured and responded to. Meditation enables a shift from habitual identification with thoughts and feelings toward a spacious, non-reactive awareness that sees phenomena as transient and impersonal.

In this way, Buddhist meditation bridges philosophy and action, turning doctrinal insights into lived realities. Without this meditative embodiment, the deepest truths of Buddhism risk remaining distant, conceptual abstractions — acknowledged intellectually but untouched in actual life.

Meditation as mental emancipation

Training the untrained mind is not a task accomplished overnight; it requires sustained effort, practice, patience, and a gradual transformation of our habitual patterns. Buddhist meditation, particularly samatha (calming) and vipassanā (insight), offers a structured approach to this process. These two complementary modes of meditation provide deliberate methods to break free from habitual reactions and cultivate a new mode of being grounded in clarity and equanimity. We will explore them in more detail in the following section.

By systematically focusing attention and observing the continuous stream of thoughts, emotions, and sensations without immediately reacting, meditation allows practitioners to directly encounter the dynamics of their own consciousness. Initially, this means simply noticing how uncontrolled and fragmented the mind’s behavior becomes when left to itself. Over time, through repeated practice, practitioners develop the capacity to recognize and interrupt automatic reactive patterns.

Rather than being compulsively drawn into every passing thought or emotional surge, the mind gradually learns to maintain a position of spacious observation. This emerging stance of autonomous, non-compulsive awareness transforms the practitioner’s relationship to experience at a fundamental level. Just as an artist refines their skill through countless hours of disciplined practice — shaping, adjusting, and steadily mastering their medium through small, patient increments, meditation strengthens the mind’s stability, clarity, and discernment through repeated, mindful engagement with the processes of consciousness itself.

The two wings of meditation: Samatha and vipassanā

Buddhism recognizes two primary modes of meditation, each addressing a different aspect of mental training necessary for liberation:

- Samatha (calming or tranquility meditation) aims to stabilize and unify the mind by cultivating sustained attention on a single object, such as the breath, a visual form, or a meditative feeling. Through repeated practice, samatha quiets the turbulence of mental restlessness, developing concentration (samādhi) and emotional equanimity (upekkhā). It provides the stillness and clarity necessary as a platform for deeper insight.

- Vipassanā (insight meditation) builds upon this stabilized foundation. It involves systematically investigating the nature of phenomena as they arise and pass away, recognizing their impermanence (anicca), unsatisfactoriness (dukkha), and non-self nature (anattā). Vipassanā sharpens discernment, revealing how suffering is perpetuated by misperception and attachment.

Both samatha and vipassanā are indispensable and interdependent. Without the stability of samatha, the mind remains too restless and fragmented to sustain deep insight. Without the discernment of vipassanā, samatha risks degenerating into mere tranquility without wisdom — a pleasant but spiritually unproductive absorption.

Every meditation practice typically begins by finding an undisturbed place, sitting in an upright yet relaxed posture, and focusing the mind on a chosen object. This object can be the breath (like in our short meditation example above), the body, or a physical item. The core of the practice is to keep the awareness anchored to this object of meditation and to gently bring it back whenever it strays. Each time the mind wanders — to a sound, a thought, a bodily sensation, or an emotion — it is an opportunity to notice this distraction without judgment and patiently escort the attention back to the object of meditation, like gently guiding a curious child back to the task at hand. Though seemingly simple, this is quite challenging, as the mind naturally tends to disrupt this focus, offering endless distractions such as bodily sensations, memories, daydreams, or mental to-do lists.

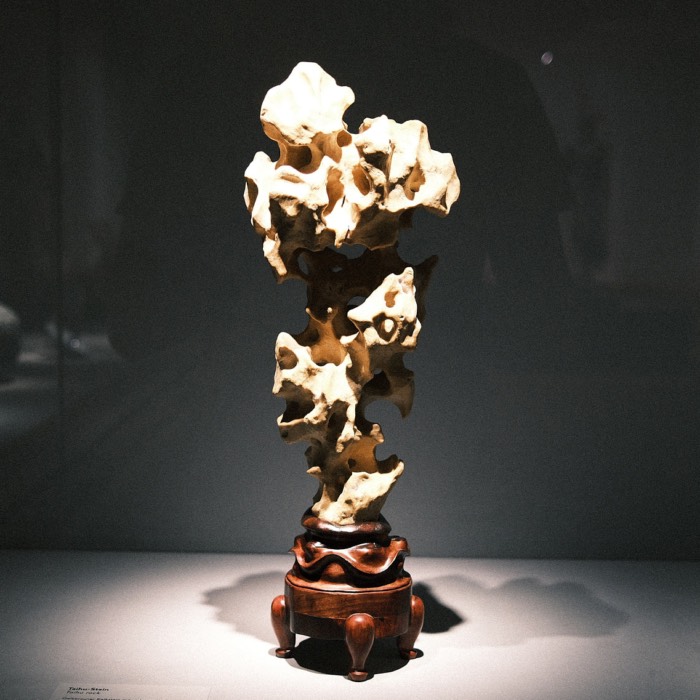

The aim of calming meditation (samatha) is to settle the mind by withdrawing attention and mental energy from these restless distractions, allowing the consciousness to become free of disturbances that cause new attachments to arise. Behind this approach lies the belief that the original nature of the mind is inherently clear, only obscured by negative factors (kilesa). Kilesa refers to mental defilements such as greed, hatred, delusion, restlessness, and doubt — disturbances that agitate the mind and prevent it from perceiving reality clearly. A common analogy compares the mind to a bowl of water: when muddy and stirred, the water cannot reflect; only by letting it settle does the water become clear and reflective.

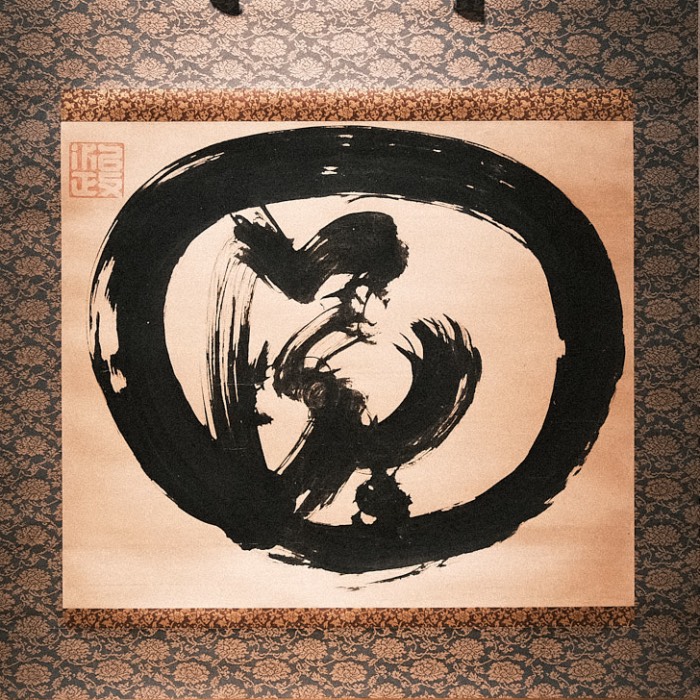

At advanced stages, this process leads to what is called “one-pointedness” (ekaggatā) of mind — a singular focus where awareness is entirely absorbed in the chosen object of meditation, free from all distractions and agitation. In this refined state, the mind no longer wavers or shifts between different sensory inputs, memories, or thoughts. Instead, it rests stably, effortlessly, and continuously on a single point of focus, like a steady flame in a windless place. The potential for this singularity exists in every fleeting moment of awareness but is usually diluted by constant mental turbulence. Only through the depth of sustained calming meditation can this natural capacity of the mind be fully gathered and revealed.

The relationship between samatha and vipassanā is often compared to the sharpening of a knife: samatha steadily hones the blade until it is smooth and sharp; vipassanā precisely carves into the truth with the refined edge. Only together do they support the transformative clarity necessary to reshape both perception and volition, ultimately dismantling the conditions that perpetuate suffering.

Thus, Buddhist meditation is not a matter of choosing either calm or insight, but of cultivating both aspects in dynamic balance — calm strengthening insight, and insight deepening calm — to realize mental freedom and the cessation of suffering.

Stages of absorption: The four jhānas

As calming meditation deepens, the mind can enter profound states of absorption known as jhāna. Siddhartha Gautama described four primary jhānas (cf. MN (Majjhima Nikāya) 141: iii 252), each representing increasingly refined levels of concentration and mental purification:

- First Jhāna: Freedom from coarse pleasures and pains, accompanied by a rapturous joy (pīti) and happiness (sukha), with discursive thought (vitakka-vicāra) still present.

- Second Jhāna: Deeper rapture and joy arise as discursive thought falls away, leading to a more unified, effortless one-pointedness of mind.

- Third Jhāna: The mind transcends rapture and rests in serene equanimity (upekkhā) and clear awareness, still infused with inner contentment.

- Fourth Jhāna: The mind moves beyond all notions of pleasure and pain, attaining pure equanimity and mindfulness — an utterly balanced and undisturbed awareness.

Elsewhere (MN 26: i 174), Siddhartha further describes how practice can proceed beyond the fourth jhāna into even subtler formless absorptions:

- The sphere of infinite space

- The sphere of infinite consciousness

- The sphere of nothingness

- The sphere of neither-perception-nor-non-perception

These deepest meditative attainments approach the cessation of sensory experience and concept formation, offering a glimpse of the unconditioned freedom (nibbāna) experienced in this life.

However, even the profound peace of jhāna remains impermanent. As blissful and subtle as these states are, they are not liberation themselves. They are still conditioned and subject to arising and passing away. Permanent freedom from suffering requires insight: the clear seeing cultivated through vipassanā.

Thus, the clarity and stability generated through samatha and jhāna are indispensable preparations for the liberating wisdom realized through vipassanā.

Insight meditation: Seeing reality as it is

The goal of insight meditation (vipassanā) is the direct, immediate recognition of reality as it truly is, particularly the three marks of existence: suffering (dukkha), impermanence (anicca), and non-self (anattā). Siddhartha Gautama’s philosophical principles — empiricism, pragmatism, and realism — are all embodied in this meditative practice. Insight meditation enables an immediate empirical experience of reality (empiricism), reveals reality as it truly is (realism), and dismantles ignorance, the root of suffering, through practical realization (pragmatism).

It is crucial to emphasize that Siddhartha taught genuine knowledge of reality is impossible without meditative training. In its natural state, the mind is too clouded by attachment and delusion to perceive things clearly. Overcoming suffering requires the eradication of ignorance, and this can only be achieved through insight meditation.

In practice, the concentrated and calmed mind is directed toward a chosen object — such as the body, feelings, mind states, or mental phenomena — and carefully observes it. This observation is not discursive or intellectual. Instead, the meditator breaks down the experience into its finest aspects, perceiving its complexity and dynamic nature with heightened clarity. This state of focused, analytical attention is what is referred to as “mindfulness” (sati).

Like a microscope revealing hidden structures, mindfulness uncovers layers of experience usually invisible to everyday perception. Siddhartha identified four primary objects for insight meditation: the body (including physical processes like breathing), feelings and their associated objects, states of consciousness, and phenomena or dhammas (including aggregates like the five skandhas and the Four Noble Truths).

Through the careful investigation of these objects, the meditator directly experiences their impermanent, process-like, and unsatisfactory nature. Take meditation on the body as an example: ordinarily experienced as a unified entity, the body disintegrates into shifting processes — breath, pulse, sensations of warmth, cold, pain in various locations, organs, and limbs. Through meditation, it becomes clear that the “body” is merely a conceptual construct, not a fixed entity. Insight dissolves this construction, undermining the illusion of selfhood.

Naturally, we identify with our body. But when it is seen as nothing more than a dynamic assemblage, the basis for that identification disappears. Extending this practice to all phenomena leads to the realization that there is nothing anywhere to cling to as “I” or “mine.” As Siddhartha succinctly put it (MN 62: i 421): “This is not mine, this I am not.”

Physical processes, thoughts, and feelings still occur and are experienced, but one learns not to identify with them — recognizing that “these are not me.” The goal of insight meditation is the direct, transformative realization of this truth.

Thus, vipassanā is not merely a cognitive understanding, but a controlled transformation of the processes that shape conscious experience and reactions to the world. It generates a new mode of experiencing reality — not through sensory novelty, but through a profound shift in perception itself.

This type of knowing is not intellectual; it is knowledge by acquaintance. It is the difference between knowing intellectually that fire is hot and personally experiencing the pain of a burn. In insight meditation, one doesn’t merely know that all things are impermanent, unsatisfactory, and selfless — one experiences it directly, and that lived realization changes everything.

Meditation and the transformation of character

Beyond cultivating clarity and insight, meditation also serves as a method for transforming the character itself. One important aim is the gradual elimination of negative mental dispositions that lead to harmful, suffering-inducing behavior, and their replacement with positive tendencies rooted in kindness, compassion, and understanding.

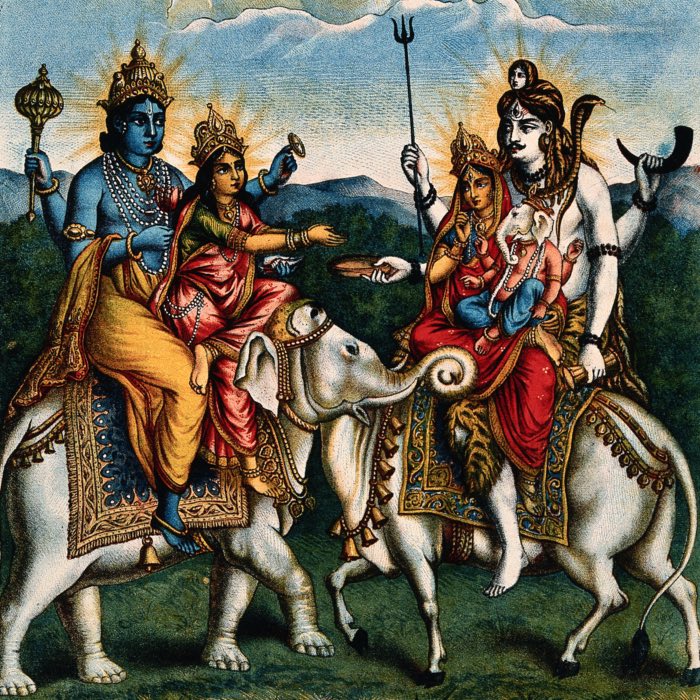

An example of this transformative practice is mettā meditation. Mettā means “loving-kindness” or “benevolence” and is one of the four brahmavihāras, or “sublime attitudes”, along with compassion (karuṇā), empathetic joy (muditā), and equanimity (upekkhā). Mettā meditation is a practice of cultivating goodwill and kindness toward oneself and others, gradually expanding this benevolence to all beings.

Contrary to common misunderstanding, mettā meditation is neither a prayer asking a higher power to benefit others, nor a magical technique that directly alters external reality. Instead, its effects are entirely internal: it reshapes the meditator’s own emotional dispositions.

Mettā meditation

To practice mettā meditation, begin by finding a quiet, undisturbed place where you can sit comfortably, upright yet relaxed. Close your eyes and turn your attention inward. Gently evoke a feeling of kindness and goodwill toward yourself, silently repeating phrases such as: “May I be safe. May I be happy. May I be healthy. May I live with ease.” Allow these words not to remain mere statements, but to gradually awaken a warm and benevolent emotional state.

Once this feeling is stable, imagine a person you love dearly. Visualize them clearly in your mind and direct the same heartfelt wishes toward them: “May you be safe. May you be happy. May you be healthy. May you live with ease.” Feel the sincerity of these wishes as if you could radiate goodwill toward them with each breath.

Gradually extend this circle of kindness further: first toward neutral acquaintances, people toward whom you feel neither strong affection nor aversion; then toward individuals with whom you experience difficulties, offering them the same unconditional wishes. Finally, embrace all beings without distinction — known and unknown, near and far, friends and enemies — with boundless goodwill.

If feelings of anger, resistance, or indifference arise during the practice, simply observe them with patience and kindness, without judgment. Each moment of returning to the intention of friendliness strengthens the mind’s new disposition, little by little transforming habitual patterns of thought and emotion.

Through consistent practice, mettā meditation reshapes the emotional foundation from which action springs, nurturing a mind that responds to the world with patience, empathy, and unconditional kindness.

Through steady practice, the mind is gradually rewired to respond to others — and oneself — with increasing benevolence, patience, and compassion.

Through regularly practicing mettā meditation, the influence of negative emotions like hatred and anger on thoughts and actions is reduced, while tendencies toward friendliness and goodwill are strengthened. Gradually, this practice diminishes the likelihood of responding to others with hostility or aggression and increases the capacity for patience, empathy, and compassion.

Since actions arise from preceding mental states — thoughts, emotions, volitions — transforming these states naturally leads to a transformed way of acting in the world. Meditation thus has an explicitly practical side: it is an instrument for the ethical transformation of character, an indispensable foundation for a life guided by compassion and wisdom.

Conclusion

Buddhist meditation addresses the fundamental human challenge of suffering (dukkha) by offering a methodical training of the mind that encompasses stabilization, insight, and ethical transformation. It is a profound system of cognitive and ethical transformation, carefully designed to address the fundamental problem of suffering (dukkha). Through the two wings of meditation — calm (samatha) and insight (vipassanā) — the mind is first stabilized and then guided toward a direct experiential realization of impermanence, suffering, and non-self.

The stages of jhāna demonstrate the mind’s capacity to attain increasingly refined states of absorption, creating the foundation for deep insight. Vipassanā then allows for a dismantling of cognitive habits that falsely impute permanence and selfhood onto transient phenomena. Through careful observation and analysis, the meditator experiences reality as it truly is, not merely as a theoretical construct but as an immediate, transformative perception.

Furthermore, meditation directly reshapes emotional dispositions and character. Practices like mettā meditation cultivate goodwill and compassion, diminishing the influence of destructive emotions such as anger and hatred. This leads not only to inner peace but also to a profound ethical transformation of behavior.

From a critical perspective, Buddhism offers several advantages over many Western approaches to mental training and psychotherapy. While modern mindfulness-based practices have adopted elements of sati, they often isolate it from its original ethical and liberating context. Western models tend to focus on symptom management — reducing stress, anxiety, or depression — without necessarily addressing the deeper structures of craving, aversion, and delusion that perpetuate suffering. In contrast, Buddhist meditation operates within an integrated framework that targets both cognitive distortions and behavioral dispositions, aiming at a fundamental reconfiguration of how reality is perceived and engaged with.

However, it must also be recognized that traditional Buddhist meditation demands significant commitment, patience, and ethical discipline — requirements that can be challenging in contemporary secular contexts. Moreover, Buddhist meditation is not a panacea for all psychological problems; it presupposes a certain degree of psychological stability and is best supported by an overall lifestyle aligned with the Eightfold Path.

In sum, Buddhist meditation presents a rigorous, empirically grounded path to freedom. It does not rely on metaphysical speculation or mystical states but on a gradual, methodical training of the mind to perceive reality accurately and to respond to it with wisdom and compassion. In doing so, it offers a realistic and practical route to the liberation from suffering, grounded in experiential knowledge rather than belief.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

For readers interested in the historical development and classical formulations of Vipassanā meditation, traditional sources such as the works of Mahāsi Sayādaw and S.N. Goenka provide additional depth and context.

comments