Buddhist eschatology and the future Buddha Maitreya

Maitreya, the future Buddha, holds a central place in Buddhist eschatology as the prophesied restorer of the Dharma in an age of moral and spiritual decline. Unlike apocalyptic visions in other traditions, Buddhist eschatology envisions cycles of decay and renewal, with Maitreya symbolizing hope, ethical restoration, and the continuity of the teachings. In this post, we examine Maitreya’s doctrinal significance, devotional practices, and cultural adaptations, highlighting his relevance across Buddhist traditions.

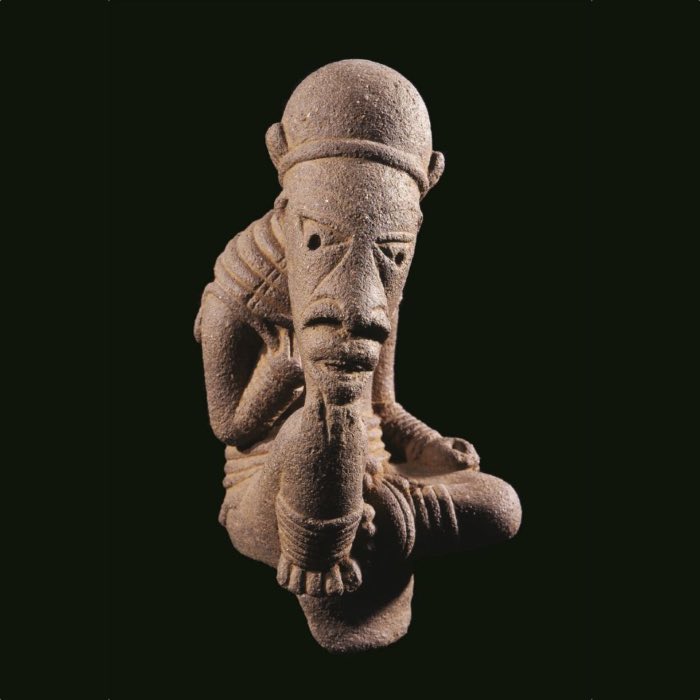

Maitreya, Gandhara-style schist statue, c. 3rd century, Gandhara (today Pakistan). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC 1.0)

Introduction

Eschatology, the study of the end times or ultimate destiny of the world, occupies a distinctive place in Buddhist thought. Unlike in many theistic traditions, where eschatology often implies a final judgment or the termination of worldly existence, Buddhist eschatology is embedded in a cosmology of endless cycles of creation and dissolution. The universe, in Buddhist understanding, goes through successive kalpas (cosmic epochs), during which Buddhas arise, teach, and then their teachings gradually decline and disappear, only to be revived anew in a future age.

This cyclical view of time, rooted in both early canonical sources and later cosmological elaborations, does not preclude eschatological concern. Rather, it reframes it. In Buddhism, eschatology is not about a singular end, but about the degeneration of the Dharma and the moral order it sustains. The concern is less with cosmic collapse than with spiritual deterioration: a decline in ethical behavior, meditative discipline, and understanding of the teachings. This decline necessitates eventual renewal, and it is in this context that the figure of Maitreya, the future Buddha, assumes his central role.

Maitreya (Sanskrit; Metteyya in Pāli) is prophesied to be the next Buddha to appear in our world system. According to both Pāli and Mahāyāna sources, he currently resides in the Tuṣita heaven, awaiting the right conditions to descend into the human realm, attain awakening, and restore the Dharma. Over time, Maitreya has emerged not only as a doctrinally sanctioned eschatological figure but also as a potent symbol of moral renewal, future hope, and even sociopolitical transformation. His image and cult have become prominent in Buddhist devotional life across Asia, reflecting the enduring human need for reassurance in times of moral or institutional decline.

Kalpas

In Buddhist cosmology, a kalpa (Sanskrit; Pāli: kappa) refers to an immense period of time, often described as an aeon or cosmic cycle. Kalpas are used to frame the cyclical nature of the universe, encompassing phases of creation, existence, destruction, and dormancy. This concept underscores the impermanence of all phenomena, including the cosmos itself, and provides a temporal context for the arising and passing of Buddhas.

Buddhist texts describe different types of kalpas, each varying in duration and significance:

- Great kalpa (mahākalpa): The longest unit of time, encompassing the full cycle of the universe’s formation, existence, destruction, and void.

- Intermediate kalpa (antara-kalpa): A smaller division within a great kalpa, often used to describe the rise and fall of human lifespans and moral conditions.

- Asaṃkhyeya kalpa: A term meaning “incalculable kalpa” (lit.: “beyond calculation”), used to emphasize the vast, incomprehensible timescales involved in cosmic and spiritual processes. In some traditions, it is quantified as 10$^{140}$.

Buddhas are said to arise at specific points within kalpas, often in response to conditions of moral and spiritual decline, to restore the Dharma. The current kalpa, known as the bhadrakalpa (“fortunate aeon”), is notable for the appearance of multiple Buddhas, including Siddhartha Gautama and the prophesied future Buddha, Maitreya. This cyclical view of time highlights the continuity of the Dharma, even as it undergoes periods of decline and renewal.

Symbolism and ethical implications

The concept of kalpas serves as a reminder of the vastness of time and the impermanence of all things. It encourages practitioners to cultivate patience and perseverance on the path to awakening, recognizing that spiritual progress often unfolds over countless lifetimes. At the same time, the cyclical nature of kalpas reinforces the idea that moral and spiritual renewal is always possible, even in the face of decline.

In this way, kalpas are not merely a cosmological framework but a profound ethical and existential teaching, emphasizing both the impermanence of the universe and the enduring potential for liberation.

The decline of the Dharma

In Buddhist thought, eschatology is intimately linked not with the end of the world per se, but with the progressive deterioration of the Dharma over time. This decline is typically described in three successive phases. The first is the age of the “true Dharma” (saddhamma), during which the teachings of the Buddha are practiced correctly, monastic discipline is maintained, and awakening is still attainable. This is followed by the “semblance Dharma” (dhamma-paṭirūpa), a period in which outward forms and rituals remain but the true spirit and efficacy of the teachings begin to wane. Eventually, this gives way to the final phase, often referred to as the degenerate age or mappō in East Asian traditions, where the Dharma is said to have all but disappeared in practice, and genuine liberation becomes exceedingly rare or impossible.

Canonical sources such as the Cakkavatti Sīhanāda Sutta (Dīgha Nikāya 26) in the Pāli Canon outline the ethical and social symptoms of this decline: diminished life spans, growing conflict, decay in moral conduct, and the breakdown of communal life. Later Mahāyāna texts, such as the Lotus Sūtra and Mahāmegha Sūtra, build upon this framework and give it cosmic and apocalyptic overtones, often placing the burden of restoration on the future Buddha, Maitreya.

Throughout Buddhist history, cultural and institutional responses to this perceived decline have varied. In some contexts, it prompted a turn toward devotionalism, focusing on faith-based paths rather than meditative or scholastic discipline. In others, it inspired reformist movements aimed at reviving monastic ethics or purifying Buddhist institutions. The rhetoric of decline has also been employed to explain historical upheavals, foreign invasions, or institutional corruption, making it both a religious and socio-political discourse. Regardless of interpretation, the doctrine of Dharma decline plays a key role in Buddhist eschatology by framing the necessity of future renewal, embodied most clearly in the prophesied arrival of Maitreya.

Mappō (末法)

In East Asian Mahāyāna Buddhism, mappō (Japanese; Chinese: Mo-fa, Korean: Malbeop) refers to the “Latter Dharma” or “Degenerate Age of the Dharma”. It designates a period in which the authentic teaching (Dharma) of the historical Buddha Siddhartha Gautama undergoes progressive decline. The concept reflects a pessimistic eschatology, asserting that while the Dharma may persist formally, its efficacy for producing enlightenment diminishes over time.

Classical Mahāyāna doctrine typically divides the post-Buddha era into three successive ages:

- Age of the True Dharma (shōbō, 正法): A period during which both correct practice and realization are possible.

- Age of the Semblance Dharma (zōhō, 像法): The external forms of the Dharma remain, but genuine insight becomes rare.

- Age of the Degenerate Dharma (mappō, 末法): Ethical decay and spiritual confusion dominate; while the teachings survive, the capacity to realize awakening through them effectively disappears.

The origin of this tripartite schema is found in Indian Buddhist apocalyptic texts (e.g. The Saddharma-smṛty-upasthāna Sūtra), but its doctrinal elaboration and historical dating developed predominantly in Chinese and Japanese Buddhism. In Japanese thought, mappō was widely believed to begin in 1052 CE, a date that influenced the rise of new religious movements emphasizing reliance on other-power (他力, tariki), such as Pure Land and Nichiren Buddhism.

Doctrinal implications and historical significance

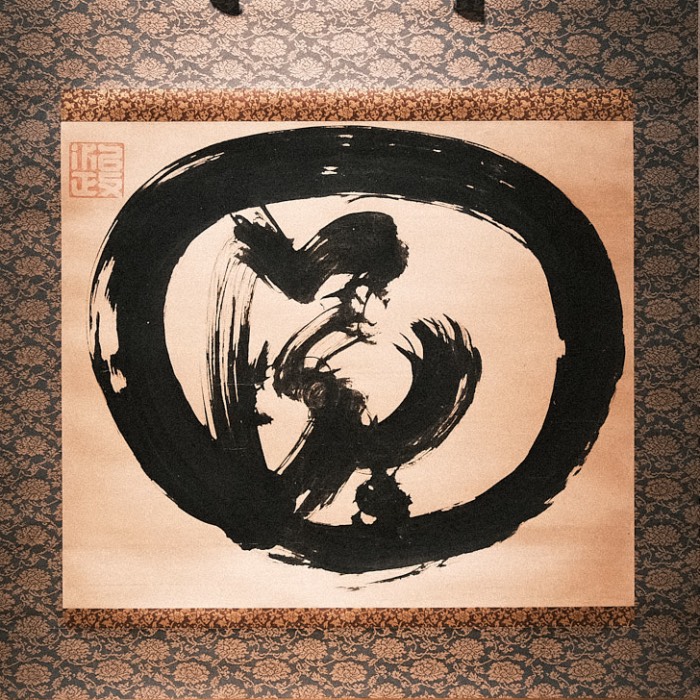

Mappō carries profound soteriological and practical implications. As self-powered practices (自力, jiriki) were deemed ineffective in this age, new emphases emerged on practices accessible to all, particularly recitation of Amitābha Buddha’s name (nembutsu), faith-based devotion, and exclusive reliance on the compassionate vows of celestial Buddhas. Teachers such as Hōnen, Shinran, and Nichiren shaped entire schools around this vision of religious decline and renewal.

The concept of mappō also served as a powerful social critique. It framed political disorder, natural disasters, and moral disintegration as signs of a deeper spiritual deterioration, thus providing both a diagnosis of and response to historical crises.

Symbolism and ethical interpretation

Though pessimistic in tone, mappō also affirms a paradoxical hope: even in times of deep decline, the Dharma continues in altered forms, offering salvation through accessible means. This reflects a core Mahāyāna theme: that compassion adapts to context. The age of mappō, while marked by loss, becomes a stage for new expressions of the Dharma, underscoring the adaptability and resilience of the Buddhist path.

In this way, mappō is not merely an eschatological warning but an ethical and existential reflection on spiritual persistence amid decline.

Maitreya as the future Buddha

Maitreya, whose name derives from the Sanskrit word maitrī (loving-kindness), is recognized across Buddhist traditions as the next Buddha who will appear in the human realm to restore the Dharma. His presence is documented in both early and later scriptures. In the Pāli Canon, the Cakkavatti Sīhanāda Sutta (Dīgha Nikāya 26) briefly describes Maitreya (Metteyya) as a future Buddha who will arise when the current world system has declined morally and spiritually. Mahāyāna texts such as the Maitreya-vyākaraṇa and Mahāvastu offer more elaborate accounts, presenting Maitreya as a Bodhisattva currently residing in the Tuṣita heaven, patiently awaiting his final rebirth.

According to these accounts, Maitreya will descend to Earth in a distant future age when the memory of Siddhartha Gautama’s teachings has entirely faded. He will be born into a time of renewed human virtue, with extended life spans and a relatively peaceful social order, thus reflecting the Buddhist understanding that conditions must be karmically ripe for a Buddha to arise. Upon attaining enlightenment under a new Bodhi tree, he will teach the Dharma anew, gathering disciples and restoring the path to liberation.

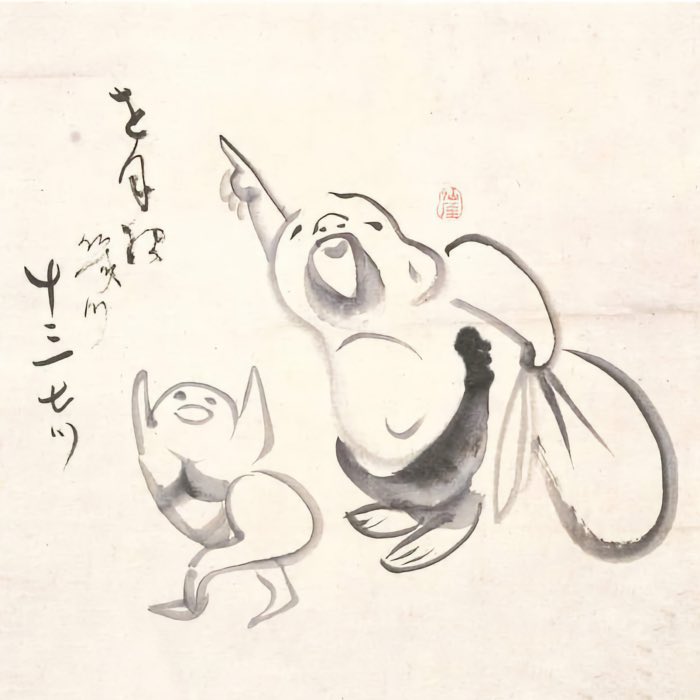

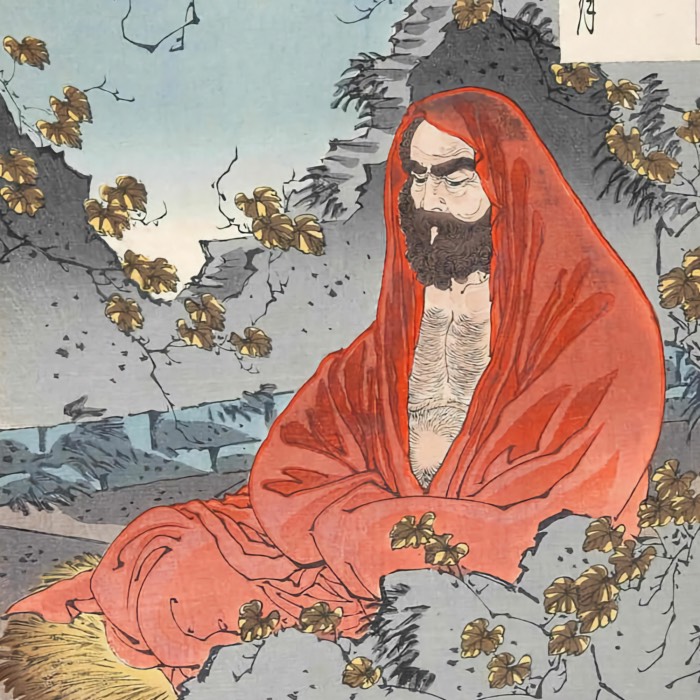

Iconographically, Maitreya is often depicted either as a Bodhisattva adorned in princely attire (especially in Mahāyāna contexts) or as a seated Buddha figure waiting in Tuṣita heaven. In Chinese folk tradition, he is also associated with the rotund, laughing figure known as Budai, interpreted as a terrestrial manifestation or precursor of Maitreya. These multiple representations reflect the wide range of cultural interpretations and expectations surrounding the figure.

Narratively and symbolically, Maitreya serves multiple functions. He embodies hope and renewal within the broader Buddhist understanding of impermanence and cyclical decay. His future arrival offers a temporal and moral anchor for practitioners living in an age of perceived decline, assuring them that the Dharma will not be extinguished forever. In this sense, Maitreya is less a distant savior than a projection of Buddhist continuity — a figure who affirms the enduring possibility of ethical rebirth and collective restoration.

Eschatological function of Maitreya

Within the cyclical framework of Buddhist cosmology, Maitreya functions as the harbinger of spiritual renewal in an age of Dharma decline. His arrival marks the re-establishment of the teachings after they have been lost for an extended period, not only as doctrine, but as lived ethical and meditative practice. According to canonical and later sources, Maitreya will appear when human beings have regained sufficient moral capacity and societal conditions have become conducive for the reintroduction of the Dharma. This links his appearance directly to the logic of karmic causality: the reemergence of a Buddha depends on the collective merit and readiness of sentient beings.

Maitreya’s eschatological function must be understood within the larger cosmological cycles of kalpas , vast cosmic time periods during which universes come into being, flourish, and dissolve. In each cycle, multiple Buddhas arise, and Maitreya is said to be the fifth in the current fortunate aeon (bhadrakalpa). His role is not to end the world, but to reinstate the path of liberation through renewed teaching. In this way, the eschatology centered on Maitreya differs fundamentally from apocalyptic visions of finality found in other traditions; it emphasizes continuity, recurrence, and the resilience of moral potential.

The figure of Maitreya also carries a symbolic and motivational function. His anticipated arrival assures practitioners that the Dharma will not disappear forever, and that cycles of decay are counterbalanced by renewal. In historical periods marked by political instability, corruption, or perceived moral decline, the hope for Maitreya’s coming has offered psychological solace and ethical encouragement. He represents a future free from confusion and conflict, grounded in compassion, clarity, and social harmony. Thus, Maitreya is not merely a remote messianic figure, but a personification of moral continuity in a transient and imperfect world.

Devotional and cultic dimensions

Devotion to Maitreya occupies a significant place in both monastic and lay Buddhist practice, particularly in times and regions where the sense of Dharma decline is strongly felt. As the anticipated restorer of the Dharma, Maitreya is not only venerated as a future teacher but also as a present source of blessing and inspiration. This veneration is expressed through prayer, meditation, ritual offerings, and the construction of images and temples dedicated to his anticipated arrival.

One of the most widespread devotional practices involves the recitation of Maitreya’s name or associated mantras, often with the aspiration to be reborn in Tuṣita heaven, i.e., the celestial abode where Maitreya currently resides, in order to encounter him and receive his teachings directly in the future. This aspiration reflects a unique combination of faith and karmic intentionality: it reinforces ethical living in the present while cultivating a long-term soteriological goal aligned with Maitreya’s eventual appearance.

Iconographically, Maitreya has been one of the most frequently represented figures in Buddhist art. Across Asia, statues of Maitreya are typically depicted in one of two major forms: as a princely Bodhisattva seated with his feet on the ground (symbolizing readiness to descend to earth), or as a seated Buddha in meditation. The former is especially common in Central Asian and early Chinese representations, while the latter is more typical in Southeast Asia. In East Asia, Maitreya is sometimes associated with the jolly, pot-bellied figure of Budai (Hotei in Japan), who came to be viewed as a manifestation or prophetic herald of Maitreya.

These visual and ritual elements of Maitreya devotion express both eschatological hope and ethical commitment. For lay practitioners in particular, devotion to Maitreya often involves aspirations for a future rebirth in a more auspicious time — an era when the Dharma will flourish anew. This forward-looking soteriology offers a counterbalance to the sense of moral and institutional decline in the present, providing a focus for both individual virtue and collective renewal. In this way, the cult of Maitreya acts as a bridge between doctrinal teachings and popular religiosity, sustaining Buddhist ethical ideals through the lens of future fulfillment.

Regional adaptations and interpretations

Across the Buddhist world, the figure of Maitreya has been subject to diverse interpretations and appropriations, shaped by local cosmologies, political conditions, and devotional needs. In Chinese Buddhism, Maitreya occupies a prominent place in both canonical and popular religious life. His association with the jolly monk Budai emerged during the later imperial period and reflects a syncretic integration with folk religious expectations. Budai, often seen carrying a cloth sack and surrounded by children, came to symbolize both prosperity and the promise of future salvation — a more approachable and familiar embodiment of Maitreya’s benevolent role.

In Tibetan Buddhism, Maitreya is venerated both as a future Buddha and as an important Bodhisattva within the Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna pantheons. Monumental Maitreya statues, such as those found in Tashilhunpo Monastery, reflect his elevated status as a symbol of universal compassion and future hope. Tibetan scholasticism also contributed significantly to the doctrinal elaboration of Maitreya through texts attributed to the Bodhisattva Maitreya and transmitted via Asaṅga, such as the Yogācārabhūmi and Abhisamayālaṅkāra. These works deepen Maitreya’s role as both a spiritual exemplar and a philosophical authority.

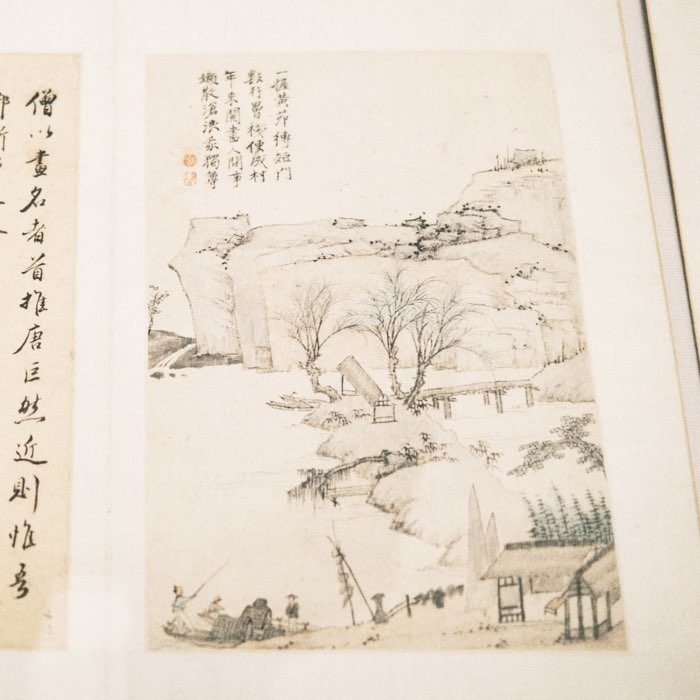

Central Asian depictions of Maitreya, especially along the Silk Road, display a transitional iconography that blends Indian, Hellenistic, and Chinese artistic influences. In places like Dunhuang, cave murals and sculptures depict Maitreya in various narrative and symbolic contexts, suggesting the importance of his cult in early transregional Buddhist networks.

Southeast Asian traditions also venerate Maitreya, though often in forms aligned with Theravāda cosmology. In Myanmar and Thailand, Maitreya is integrated into popular eschatological beliefs, with some lay communities venerating him as a bringer of future peace and harmony. His name frequently appears in protective chants and is invoked during times of political unrest or religious anxiety.

In various regions, belief in the coming of Maitreya has also intersected with millenarian movements, i.e., religiously inspired campaigns anticipating an imminent transformation of society. In times of war, colonial pressure, or dynastic collapse, Maitreya was sometimes invoked as a divine liberator who would usher in a new moral and political order. Such movements, while often marginalized by orthodox institutions, reveal the political potency of Maitreya imagery and its capacity to articulate visions of renewal beyond purely soteriological concerns.

Taken together, these regional adaptations demonstrate the dynamic role of Maitreya in Buddhist eschatology. His image becomes a vehicle for expressing both doctrinal continuity and cultural transformation: a future Buddha who speaks in the voices of many communities.

Philosophical and soteriological interpretations

The figure of Maitreya occupies a rich interpretive space that spans literal belief, symbolic meaning, and ethical aspiration. For many traditional communities, Maitreya is a literal, sentient being residing in Tuṣita heaven, destined to become the next Buddha. In this view, belief in Maitreya functions as an article of faith rooted in canonical prophecy and supported by centuries of ritual and devotional practice. Such belief carries both eschatological hope and soteriological consequence: through moral conduct and spiritual cultivation, one might be reborn in Tuṣita and personally encounter the future Buddha.

However, Buddhist philosophical traditions, particularly in Mahāyāna thought, have long explored more symbolic and abstract understandings. From this perspective, Maitreya can be interpreted as a personification of loving-kindness (maitrī) or as a narrative embodiment of the cyclical rhythm of decline and renewal that structures the cosmos and moral life. His future arrival becomes not a cosmological certainty but an archetype of ethical optimism: the idea that compassion and wisdom can reemerge even in times of darkness. Maitreya thus serves as an ethical ideal that invites practitioners to live as if the Dharma is always in need of restoration — beginning with oneself.

Critical perspectives on Buddhist eschatology have emerged particularly in modern contexts, where literal readings of cosmic prophecy are often questioned or reinterpreted in light of historical consciousness and rational critique. Some scholars view the doctrine of Maitreya as a skillful means (upāya), a narrative device that maintains continuity of hope in the face of Dharma decline. Others critique it as potentially distracting from the immediate, here-and-now practice of the Eightfold Path. These debates reflect a broader tension within Buddhist tradition: between the mythical and the philosophical, the devotional and the critical.

Nevertheless, the concept of Maitreya contributes to the continuity of the Dharma by offering a narrative structure through which Buddhist ethics can be reanimated and transmitted. Whether taken literally or metaphorically, Maitreya affirms the idea that the Dharma is not fixed in the past but dynamically reemerges in new forms — through future Buddhas, but also through renewed human effort and collective aspiration. The myth of Maitreya thus sustains not only hope for future liberation but a present commitment to ethical renewal.

Conclusion

The figure of Maitreya occupies a singular role in Buddhist eschatology, unifying doctrinal predictions, devotional hopes, and ethical renewal. Across diverse traditions and historical contexts, Maitreya has come to represent not the end of the world, but the cyclical regeneration of the Dharma in times of moral and spiritual decline. He is a reminder that impermanence, which governs the decay of even the Buddha’s teachings, also permits renewal through karmically conditioned rebirth and insight.

Maitreya’s appeal lies in this dual nature: both a future Buddha prophesied to restore the Dharma, and a symbol of enduring ethical optimism amid decay. He brings together the continuity of Buddhist cosmology with the existential need for future-oriented meaning. In his anticipated arrival, communities have found motivation for ethical behavior, comfort in times of instability, and a vision of a restored moral and social order.

Far from encouraging passivity, belief in Maitreya has often galvanized reformist movements, revitalized devotional practices, and provided a flexible vehicle for addressing cultural and political anxieties. Whether approached as a literal being in Tuṣita heaven, a mythic embodiment of loving-kindness, or a symbol of aspirational ethics, Maitreya continues to serve as a vital node in the Buddhist imagination.

Buddhist eschatology, as expressed through the Maitreya tradition, does not predict an apocalyptic termination, but affirms the possibility of cyclical moral restoration. In this light, it functions not as prophecy in the predictive sense, but as a framework for ethical resilience — a reminder that spiritual insight and compassion are always capable of returning, whether in cosmic time or in human effort.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments