The Three Jewels of Buddhism: Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha

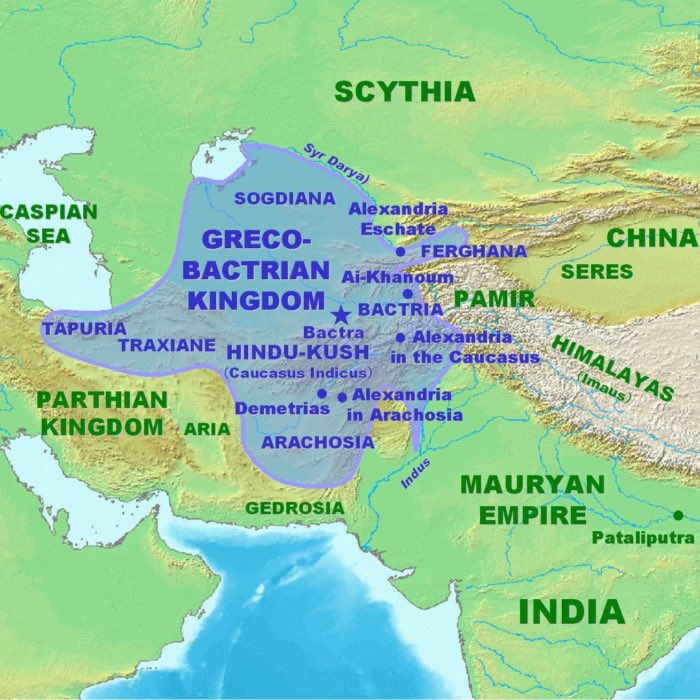

In the doctrinal and lived structure of Buddhism, the Three Jewels, also known as the Triple Gem or Triratna, represent the foundational elements to which all adherents turn for guidance and refuge. These three elements are the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. While they are often referred to in a ritualized formula, their significance extends far beyond mere recitation or symbolism. Each jewel embodies a distinct aspect of the Buddhist framework: the exemplar, the teaching, and the community. An objective examination of these three pillars provides insight into how Buddhism has functioned as a living tradition across centuries and cultures. This post aims to explicate the conceptual framework of the Three Jewels, with particular attention to the Sangha and its structural and social functions.

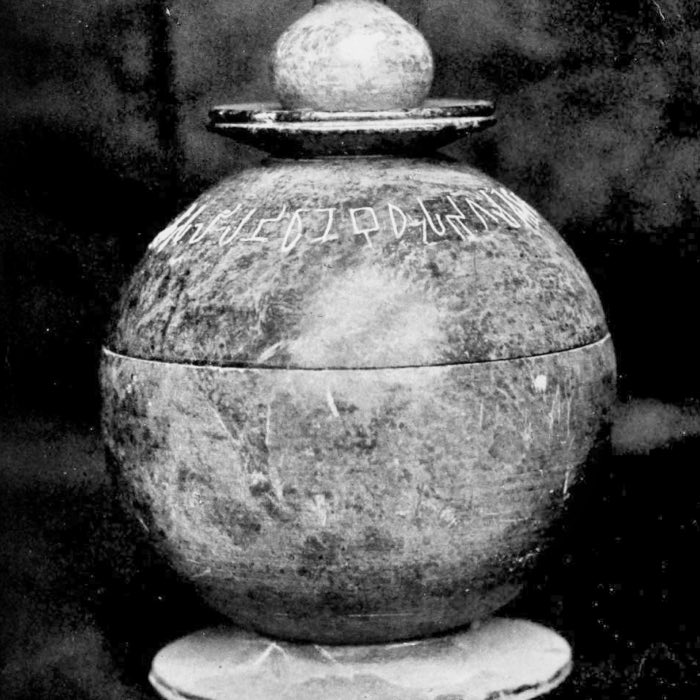

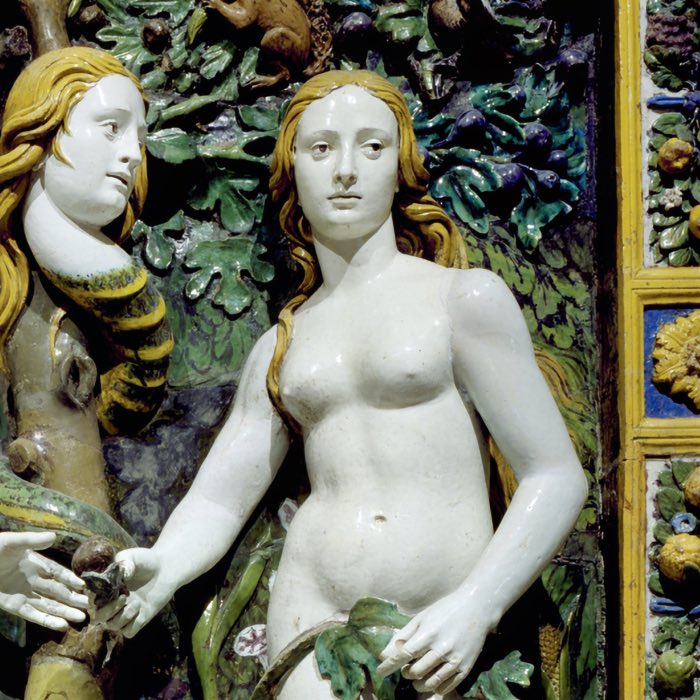

Adoration of the three jewels, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. To become a Buddhist, one takes a three-fold refuge by speaking a solemn formula: “I take refuge in the Buddha, refuge in the doctrine, refuge in the monks’ community.” The trinity of the Buddha, doctrine and monks’ order is called the three jewels (triratna). Here they are symbolized by three wheels and worshipped by monks. Exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, 2023.

Adoration of the three jewels, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. To become a Buddhist, one takes a three-fold refuge by speaking a solemn formula: “I take refuge in the Buddha, refuge in the doctrine, refuge in the monks’ community.” The trinity of the Buddha, doctrine and monks’ order is called the three jewels (triratna). Here they are symbolized by three wheels and worshipped by monks. Exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, 2023.

The Buddha: Siddhartha Gautama as the exemplar

The first of the Three Jewels, the Buddha, refers specifically to Siddhartha Gautama, the historical figure who lived and taught in northern India during the 5th to 4th century BCE. Siddhartha’s path from sheltered prince to enlightened teacher serves as a paradigmatic model within the Buddhist tradition. Importantly, early canonical texts do not present Siddhartha as a divine being, but as a human who achieved a state of profound insight and liberation through disciplined practice and introspection.

His teachings, grounded in his personal experience of awakening under the Bodhi tree, became the cornerstone of a spiritual system that encourages critical inquiry, ethical living, and mental cultivation. Over time, however, subsequent traditions have imbued his persona with metaphysical attributes, and alternative Buddhas and Bodhisattvas have emerged in Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna schools. Still, in the context of the Three Jewels, the “Buddha” remains primarily an exemplar of what a human being can potentially achieve.

To take the Buddha as an example is to acknowledge that Siddhartha, a historically ordinary human being, achieved enlightenment through effort, insight, and perseverance — demonstrating that this state is potentially accessible to all. His life serves as empirical proof within the tradition that liberation is not a supernatural gift but the result of practice rooted in the human condition. In this view, Siddhartha’s attainment is not a miracle, but a consequence of applying principles available to anyone willing to engage deeply with the existential realities of life and mind. The implication is not only motivational but structural: if one human can attain awakening through specific actions and insights, then the conditions for such awakening are universally present and reproducible.

Moreover, in light of the Buddhist principle of interdependence (paṭiccasamuppāda), his achievement is not isolated or exclusive: it reverberates through time and space, implicating all beings. In this perspective, the transformation attained by Siddhartha is simultaneously a transformation within others, suggesting that his awakening is, in some sense, also ours. This collective dimension frames enlightenment not only as an individual milestone but as a relational event woven into the fabric of all existence.

The Dharma: The teaching and its interpretive evolution

The second Jewel, the Dharma, encompasses the body of teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama as well as the broader philosophical, ethical, and meditative frameworks developed by later schools. In its most essential form, the Dharma refers to the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path — formulas that encapsulate the diagnosis of suffering and the prescription for its cessation.

However, the Dharma is not static. Across centuries, as Buddhism migrated through diverse cultures — from Indian to Chinese, Tibetan, Japanese, and Southeast Asian contexts — the interpretation of the Dharma adapted to new intellectual and spiritual climates. This resulted in the development of numerous commentaries, philosophical treatises, and liturgical practices, each claiming fidelity to the original insight of Siddhartha. In this way, the Dharma operates both as a textual corpus and as a living interpretive tradition, subject to historical and doctrinal evolution.

The Sangha: Community as social and doctrinal structure

Historical origins of the sangha

The third Jewel, the Sangha, refers to the community of individuals committed to practicing and preserving the Dharma. Historically, this community began with Siddhartha Gautama’s first disciples, who joined him after his awakening and formed a mendicant order. The early Sangha was a monastic institution, composed of bhikkhus (monks) and later bhikkhunīs (nuns), who adhered to a codified set of precepts (the Vinaya) and lived communally.

The formation of this monastic community had practical as well as doctrinal implications. It allowed for a stable transmission of teachings in an oral culture. In the earliest phases of the tradition, Siddhartha’s teachings were not written down but transmitted orally through disciplined recitation and memorization by the monastic community. This method of preservation played a critical role in safeguarding the integrity and continuity of the Dharma before the advent of written texts. It also offered a model of renunciation and discipline, and facilitated a degree of institutional continuity after the death of Siddhartha. In this respect, the Sangha was more than a collection of practitioners — it was a structural backbone that enabled the survival and propagation of Buddhism.

For Siddhartha himself, the Sangha was not a peripheral aspect of his vision but an essential component for the realization of his teachings. He saw monastic renunciation — leaving behind household life, possessions, and familial ties — as a necessary precondition for fully pursuing the path to awakening. According to early canonical texts, Siddhartha explicitly stated that his path was one for those who had “gone forth” from lay life. The decision to abandon worldly attachments was intended not as a rejection of society but as a deliberate and radical act of freedom, enabling practitioners to confront suffering without distraction and to cultivate wisdom and concentration in a supportive environment. In this context, the Sangha served as both a sanctuary and a crucible: a place of protection and a site of transformation. Beyond its structural and symbolic role, the Sangha also functions as a real-time support system for individual practice. By living and practicing among fellow monastics, individuals are constantly reminded of their commitments, challenged to deepen their understanding, and held accountable by a shared ethical and meditative discipline. The communal rhythm of monastic life — marked by chanting, meditation, study, and mutual service — creates an environment in which distractions are minimized and clarity of purpose is reinforced. For Siddhartha, such collective cultivation was not a compromise of individuality but a necessary matrix for the realization of insight and liberation. To become part of the Sangha was, in Siddhartha’s framework, not simply to join a community but to enter into a new existential orientation entirely.

At the same time, it should be emphasized that achieving enlightenment is not confined to monastics or members of the Sangha. Lay practitioners, too, are considered capable of attaining liberation, though the path may be more arduous due to the persistent entanglements of daily responsibilities, attachments, and distractions. The monastic Sangha offers an environment intentionally designed to minimize these obstacles and to support disciplined practice, which is why it is often viewed as a more conducive setting for spiritual progress. Nevertheless, the potential for awakening remains open to all individuals, regardless of their social or institutional affiliation.

Sangha and lay interaction

Though originally referring to ordained members, the term Sangha has also been extended in various contexts to include lay followers who support monastics and engage in ethical and meditative practices themselves. This broader definition reflects the interdependence between monastic and lay communities in many Buddhist societies.

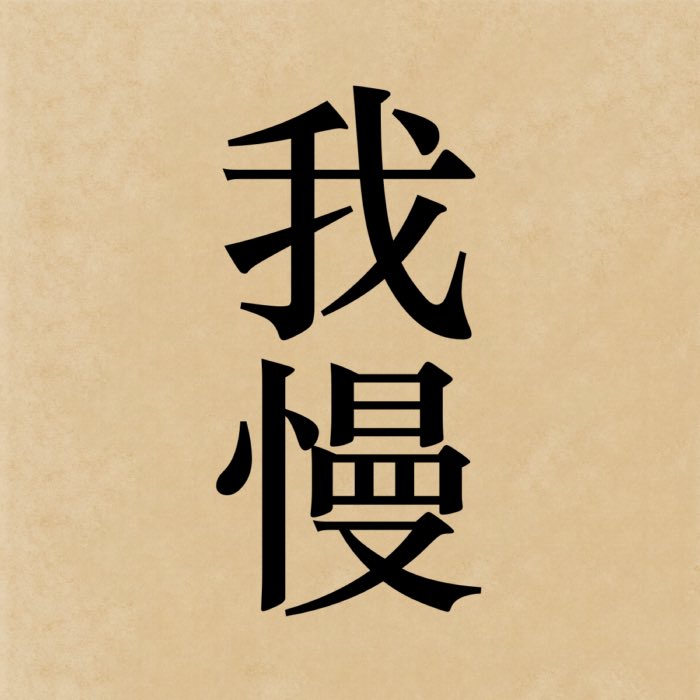

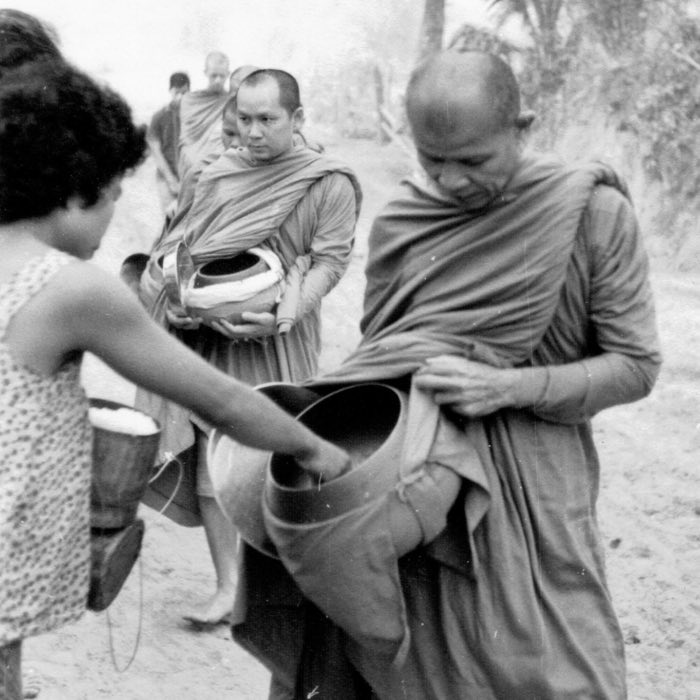

Monastics often rely on lay donors for material support — food, clothing, shelter — while laypeople benefit from the Sangha’s role in preserving the Dharma, offering teachings, and providing moral exemplars. This symbiotic relationship is not merely one of charity but is rooted in the Buddhist concept of dāna (generosity). The offerings made by laypeople are understood not as alms in the Western sense, but as a grateful opportunity to cultivate merit and generate good karma. In turn, monks do not express gratitude in the conventional way — such as by saying thank you — because the act of giving is seen as intrinsically beneficial to the giver. The monastics provide a field of merit (puññakkhetta) through their disciplined life, and the lay community gains spiritual benefit by supporting them. This mutual exchange of spiritual and material sustenance has allowed the Sangha to occupy a dual role: both as a custodian of doctrine and as a social institution embedded in local and regional cultures.

Sangha as a doctrinal authority

Within doctrinal frameworks, the Sangha also performs a crucial interpretive function. Councils convened after Siddhartha’s death — most notably the First Council — sought to systematize and preserve the teachings. These gatherings and their outcomes were legitimized by the authority of the Sangha. Over time, interpretive debates among different factions led to the development of various schools and sects, each claiming a lineage of legitimacy rooted in their connection to the early Sangha.

Thus, the Sangha functions not only as a repository of textual transmission but also as a site of interpretive power. Its authority in defining orthodoxy and orthopraxy has shaped the contours of Buddhist philosophy and practice through centuries. The process of doctrinal clarification and institutional continuity has also contributed to the consolidation of Buddhist identity across different regions and historical epochs. In this sense, the Sangha operates as both a guardian and a generator of tradition, ensuring not only the preservation of foundational teachings but also their relevance and adaptability within shifting cultural and intellectual landscapes.

Sociopolitical dimensions of the Sangha

In many regions, especially in Southeast Asia and Tibet, the Sangha has also played a prominent role in governance, education, and public morality. In certain historical periods, kings and state authorities have conferred upon the Sangha a privileged position, regulating its composition and supporting its infrastructure. In return, the Sangha has often lent religious legitimacy to state power, sometimes acting as a stabilizing force and moral compass for the broader society. The Sangha, in these contexts, was not merely a passive recipient of royal patronage but a co-architect of sociopolitical order, shaping norms, legal codes, and cultural identity through its ethical and doctrinal influence.

This role is not confined to the past but continues in the present. In Thailand, for example, Buddhist monasteries frequently serve as community centers that provide education, shelter, and care for children, particularly in cases where families are unable to afford formal schooling. Monks often act as informal educators and mentors, transmitting both religious and practical knowledge. Similar roles can be observed in countries like Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia, where monastic institutions contribute significantly to local welfare. In these societies, the Sangha remains an indispensable part of the social fabric, sustaining not only religious life but also the moral and educational infrastructure of entire communities.

However, this proximity to political power has also exposed the Sangha to institutional stagnation and complicity. Periods of corruption, rigidity, or conservatism within monastic communities have provoked reform movements, such as the Theravāda revival in 19th-century Sri Lanka or various modernist reinterpretations in East Asia. In these moments, internal critiques and grassroots movements challenged the Sangha’s entanglement with worldly power, advocating a return to simplicity, ethical purity, and direct engagement with foundational teachings. Such reform efforts illustrate the dynamic tension within Buddhist history between institutional preservation and spiritual renewal.

Conclusion

The Three Jewels — Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha — serve not only as points of reverence within Buddhist practice but as conceptual pillars that have shaped the tradition’s historical trajectory and contemporary relevance. The Buddha, represented by the life and example of Siddhartha Gautama, functions as a model for human potential rather than a divine figure. His enlightenment demonstrates that liberation is attainable through personal effort and insight, reinforced by the interconnected nature of all beings. The Dharma, in turn, reflects a living and evolving body of teachings, flexible enough to adapt across centuries and cultures while retaining its core concern with the cessation of suffering. Finally, the Sangha emerges as the institutional and communal structure that not only preserves but actively regenerates Buddhist thought and practice.

Among the Three Jewels, the Sangha is perhaps the most sociologically intricate. It functions simultaneously as a spiritual community, a doctrinal authority, and a societal institution. Historically rooted in monastic renunciation, the Sangha has become a space for deep spiritual cultivation and a matrix of moral, educational, and cultural influence. Its relationships with laypeople, built on the mutually beneficial exchange of support and merit, create a unique model of religious economy that differs markedly from the contractual or transactional dynamics often seen in Western religious traditions.

From a comparative standpoint, one might argue that Buddhism offers an especially coherent integration between individual transformation and communal responsibility. Where Western thought — especially in its modern secular iterations — often places emphasis on the autonomous individual or the abstract collective, Buddhism embeds personal enlightenment within a context of interdependence. The Sangha exemplifies this by situating individual practice within a living community of mutual accountability, moral encouragement, and shared purpose. Enlightenment, then, is not merely an inward journey but a relational and contextual process.

At the same time, the tradition is not without its challenges. The same structures that support continuity and collective strength can also inhibit change or become complicit in political and cultural conservatism. Yet, as Buddhist history shows, the tradition has proven capable of critical self-reflection and reform. In this way, the Three Jewels remain not only symbols but active agents in the unfolding story of Buddhism.

References and further readings

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments