The Bodhisattva: Mahāyāna ideal of compassion

What does it mean to be free? In early Buddhism, liberation is portrayed as the final release from saṃsāra, a cessation of craving, ignorance, and rebirth. But Mahāyāna Buddhism reimagines this freedom in a radically relational way. Here, awakening is not the end of the path, but its beginning: the bodhisattva, one who is fully awakened, chooses to remain within the world of suffering out of boundless compassion. In this post, we explore the bodhisattva ideal as both an ethical orientation and a philosophical revolution: A vision of enlightenment that turns inward insight into outward action, and personal freedom into universal care.

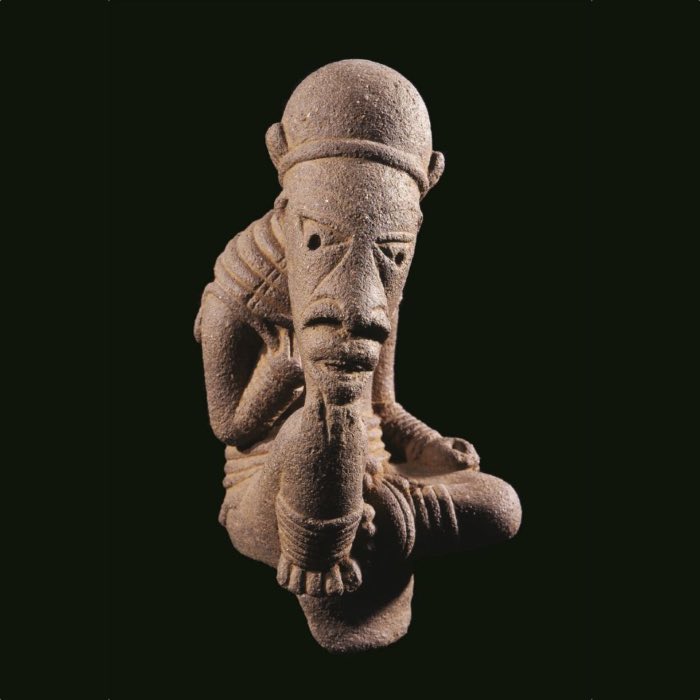

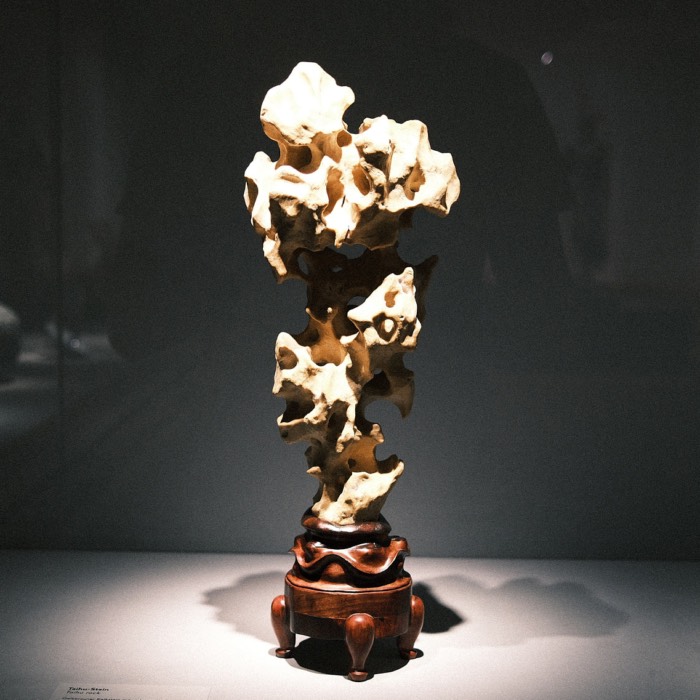

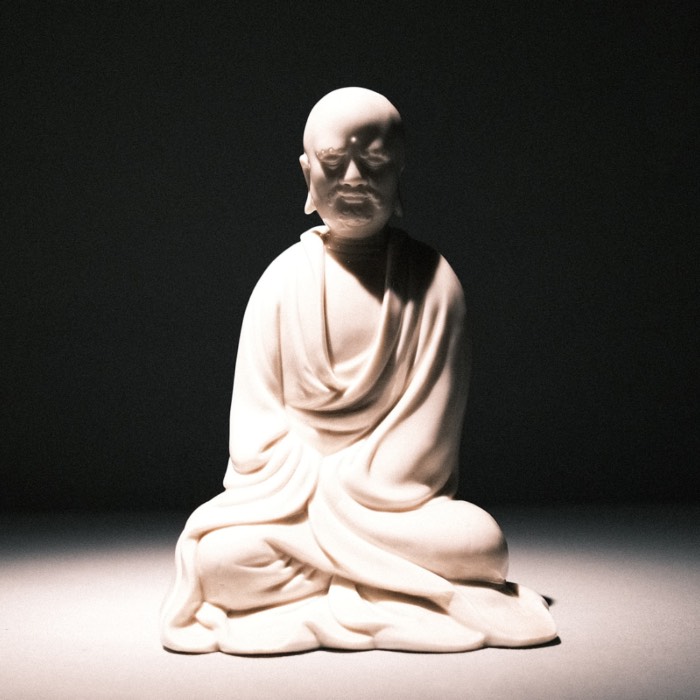

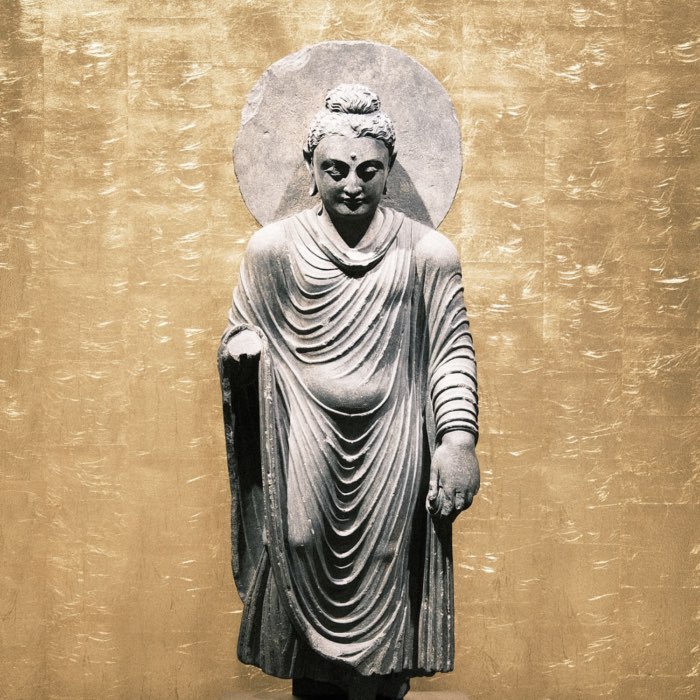

Bodhisattva with lotus flowers, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, 2023.

Bodhisattva with lotus flowers, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, 2023.

Introduction

The bodhisattva, a compound of “bodhi” (awakening) and “sattva” (being or hero), refers to one who aspires toward full enlightenment not for personal liberation alone, but for the benefit of all sentient beings. Unlike the Arhat, whose path in early Buddhism culminates in individual liberation and the cessation of rebirth, the bodhisattva delays their own final nirvana in order to remain within saṃsāra and assist others in awakening.

This ideal rose to prominence in the early centuries of the Common Era with the emergence of Mahāyāna Buddhism. In foundational texts such as the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā and the Lotus Sūtra, the bodhisattva is portrayed not only as a supremely compassionate figure but also as a model of profound wisdom. These texts reoriented the goal of Buddhist practice from personal liberation to universal salvation, emphasizing the cultivation of karuṇā (compassion) and prajñā (insight into the emptiness of all phenomena) as the two wings of the bodhisattva path.

The bodhisattva ideal does not reject early Buddhist insight; rather, it reframes it. Where the Arhat cuts through illusion to escape the cycle of rebirth, the bodhisattva sees that rebirth itself is empty and thus can be navigated with selfless intent. The contrast is not one of opposition, but of scope and emphasis: from ending suffering for oneself to shouldering the suffering of all.

Doctrinal foundations

At the heart of the bodhisattva path lies the bodhisattva vow (pranidhāna), a solemn and open-ended commitment to seek complete awakening (samyaksaṃbodhi) not for oneself alone, but so that all beings may be liberated from suffering:

- “However innumerable sentient beings are, I vow to save them all.

- However inexhaustible the afflictions are, I vow to extinguish them all.

- However immeasurable the Dharma teachings are, I vow to master them all.

- However endless the Buddha’s path is, I vow to follow it to completion.”

This vow is not a one-time declaration, but a continuous orientation: a radical shift from self-concern to boundless responsibility. It encapsulates the core Mahāyāna spirit: compassion without end and wisdom without attachment.

To actualize this vow, the bodhisattva cultivates the pāramitās, the perfections or transcendent virtues, which serve as the foundational training of their path. Traditionally listed as six, and later expanded to ten, they include:

- generosity (dāna),

- ethical discipline (śīla),

- patience (kṣānti),

- energetic effort (vīrya),

- meditation (dhyāna), and

- wisdom (prajñā).

Each pāramitā is not a rigid moral prescription but a mode of being that arises naturally from insight into the non-dual nature of reality. Practicing generosity, for instance, is not simply giving away material things, but letting go of the very notion of ownership and self.

One of the most distinctive features of the bodhisattva ideal is the willingness to be reborn endlessly in the realms of suffering to aid others. This is not a resignation to saṃsāra, but a fearless engagement with it, thus, a compassionate resolve to make suffering itself the ground of awakening. Rather than seeking escape from cyclic existence, the bodhisattva treats every birth, every form, and every encounter as an opportunity to alleviate pain, share insight, and embody the Dharma.

This orientation marks a fundamental departure from the Arhat’s path. While the Arhat aims to end saṃsāric existence once and for all, the bodhisattva willingly returns to it, not out of ignorance or clinging, but from a deep realization that saṃsāra and nirvana are not-two. As long as beings remain deluded, the bodhisattva sees no meaningful liberation that excludes them.

Even rebirth, often seen in early Buddhism as a condition to be overcome, is here transfigured: it becomes the very stage upon which compassion and wisdom are enacted. Rebirth is not bondage when the illusion of a self that suffers it has been seen through. Instead, it becomes a dynamic expression of non-attachment, the capacity to be wherever needed, without self-concern or expectation.

This concept of infinite return thus reflects a radical transformation in the practitioner’s relationship to time, identity, and liberation. Time is no longer a linear chain to be broken, but a boundless expanse of responsive presence. The self is no longer a burden to be extinguished, but a vehicle through which awakening takes form. Liberation is no longer a solitary endpoint, but an open field of compassionate activity, a vision in which the path itself becomes indistinguishable from its fulfillment.

Psychological and ethical dimensions

Far from being an unattainable spiritual archetype, the bodhisattva represents a living orientation: a practical and evolving training of the heart and mind in daily life. Whether lay or monastic, beginner or seasoned meditator, anyone who cultivates bodhicitta and acts with the intention to support others on the path is already walking the bodhisattva path.

The bodhisattva path transforms the inner architecture of the practitioner, not merely by refining behavior, but by reshaping perception and motivation at the most fundamental level. At the core lies the principle of self-transcendence, not by rejecting the world, but by dissolving the delusion of a separate self through boundless compassion. Whereas the early Buddhist model often emphasized detachment and restraint as means to liberation, the bodhisattva discovers freedom through radical connectedness: by attending to the suffering of others as indistinguishable from their own.

This shift is rooted in a deep cultivation of non-dual awareness. The bodhisattva does not operate from a self who acts compassionately toward an other, but rather from an experiential insight into the interdependence and emptiness (śūnyatā) of all things. Compassion is no longer a moral obligation, but a spontaneous responsiveness, like a hand reaching out to soothe a burn on the foot. There is no calculation or hesitation, only the natural functioning of wisdom freed from self-centered grasping.

Bodhicitta, the “mind of awakening”, is the psychological engine and ethical heart of the bodhisattva’s life. It arises as both an aspiration and a commitment: the deep wish that all beings be liberated, and the unwavering resolve to actualize that wish through one’s own awakening. Bodhicitta dissolves the false boundary between personal and universal liberation. It is not merely good will, but a restructuring of intention at the deepest level: a redirection of all thought, speech, and action toward the shared liberation of all sentient life.

Thus, the bodhisattva’s ethics are not governed by external rules, but by inner clarity. Their actions emerge not from suppression of desire, but from the absence of possessive identity. In this way, the psychological transformation and ethical orientation of the bodhisattva are inseparable, two facets of a single, liberated presence in the world.

Karma and the Bodhisattva’s return

While both the Arhat and the bodhisattva dissolve the illusion of a separate self, their relationship to karma and rebirth diverges in a crucial way. The Arhat breaks the karma–self loop completely and does not return to saṃsāra. The bodhisattva, however, returns to saṃsāra, not out of ignorance or residual karma, but out of awakened compassion.

The karma–self loop and the Arhat

In early Buddhist analysis, the feedback loop between karma and the illusion of self works like this:

Intentional action (karma) arises from ignorance (avijjā), craving (taṇhā), and aversion (dosa). These actions are typically motivated by the assumption of a stable “I”: I want, I fear, I act. Each karmic act further reinforces the illusion of this “I”, because experience is interpreted as happening to me. This feedback loop creates momentum that conditions future mental and physical states, including rebirth. As long as craving and delusion persist, the cycle of

karma → self → karma → self

perpetuates. The Arhat breaks this loop: they act without appropriation, without “I-making”, and without craving. As a result, their actions do not generate new karma, and the illusion of self dissolves completely.

The Bodhisattva’s transcendence and return

The bodhisattva also sees through the illusion of self and acts without egoic appropriation. However, their path diverges in that they voluntarily return to saṃsāra, motivated by bodhicitta, the vow to liberate all beings. Their actions are no longer karmically binding, because they are not rooted in ignorance, craving, or self-reference. Instead, they are manifestations of spontaneous compassion and wisdom.

| Aspect | Arhat | Bodhisattva |

|---|---|---|

| Karma generation | Ceased; no self-clinging, no karmic momentum | Ceased in egoic sense, but karma may arise as compassionate action, free of appropriation |

| Motivation for action | Freedom from saṃsāra | Compassion for others’ liberation |

| Basis of continued rebirth | No rebirth; karmic cycle ends | Voluntary rebirth, which is not driven by karma but by vow (praṇidhāna) and non-dual awareness |

| Nature of action | Non-karmic, spontaneous, non-binding | Non-karmic, spontaneous, yet skillful (upāya) and responsive to suffering |

| Relation to illusion | Illusion of self dissolved, no need to return | Illusion of self dissolved, return arises from seeing saṃsāra and nirvāṇa as not-two |

In this sense, the bodhisattva is not caught in the karma–self loop but re-enters it without being bound. Their activity is an expression of freedom, not compulsion. Saṃsāra becomes the field of compassionate play, not a prison to escape, but a context in which wisdom acts.

This voluntary return would not be possible without bodhicitta, the awakened mind of compassion. It is bodhicitta that transforms the bodhisattva’s insight into an active vow to remain accessible to others. Without it, there would be no momentum for reengagement, no karmic compulsion, and thus no return. But with bodhicitta, return becomes a gesture of love: the bodhisattva freely chooses to be reborn, to guide, serve, and liberate others. In this way, bodhicitta is not merely the start of the bodhisattva path; it is what sustains and completes it.

Mythological and cultural representations

The bodhisattva ideal is not confined to philosophical or ethical doctrines; it finds vivid and enduring expression in the mythologies, rituals, and artistic traditions of Buddhist cultures across Asia. These cultural manifestations both reflect and shape how communities understand and embody the path of the bodhisattva in everyday life.

Among the most beloved and widespread figures is Avalokiteśvāra (Guanyin in Chinese, Kannon in Japanese), the bodhisattva of infinite compassion. Avalokiteśvāra is said to hear the cries of all beings and to manifest in countless forms, male, female, human, divine, to provide comfort and aid wherever suffering exists. In East Asia, Guanyin evolved into a maternal figure of mercy, embodying a universal availability that made the bodhisattva ideal intimately relatable to lay practitioners.

Mañjuśrī, the bodhisattva of wisdom, complements Avalokiteśvāra’s compassion with penetrating insight. Wielding a flaming sword that cuts through ignorance and holding a book of prajñā, Mañjuśrī represents the uncompromising clarity necessary for liberation. In many traditions, he serves as the patron of scholars and meditators alike, symbolizing the essential role of insight on the path.

Other prominent bodhisattvas include Kṣitigarbha (Sanskrit; Pāli: Kshitigarbha; Jizō in Japanese), the guardian of beings in hell realms and protector of children and travelers, and Samantabhadra, who represents virtuous action and the expansive vow to practice the Dharma for the benefit of all beings. Each of these figures embodies specific qualities of the bodhisattva path, offering aspirants both devotional focus and concrete archetypes of compassion in action.

Through sculpture, painting, chants, theater, and storytelling, these bodhisattvas have become deeply woven into the social and aesthetic fabric of Buddhist cultures. They not only serve as objects of veneration but also as role models and moral mirrors, embodying the path that practitioners are encouraged to emulate. In this way, the mythological dimension of the bodhisattva ideal does not distance it from practice, but brings it to life in the shared world of the senses, imagination, and community.

Philosophical deepening in Mahāyāna thought

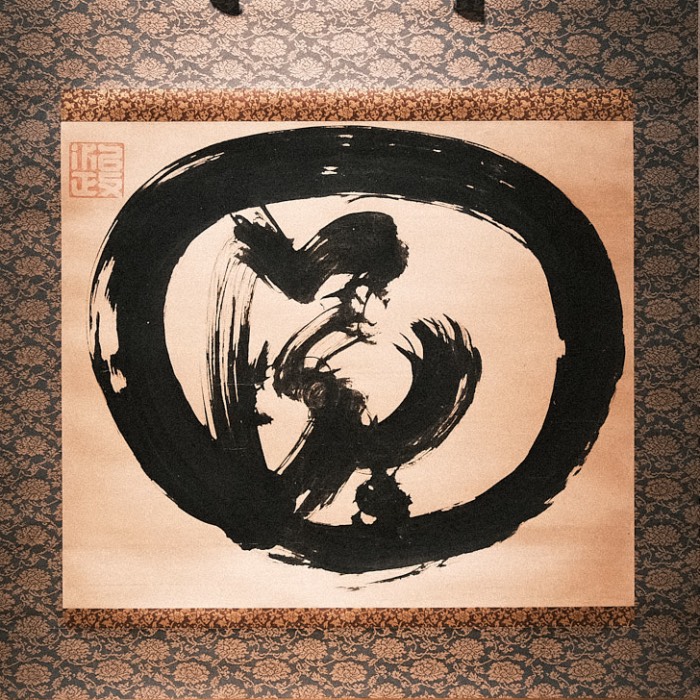

The bodhisattva ideal in Mahāyāna Buddhism is not merely a matter of moral commitment or devotional inspiration; it is grounded in a profound reconfiguration of how reality itself is understood. Central to this philosophical deepening is the concept of śūnyatā, emptiness, which expresses the radical interdependence and lack of inherent essence in all phenomena. From this view, all things, including the self, other beings, and even enlightenment itself, arise dependently and are empty of fixed identity.

This insight has profound implications for the bodhisattva’s activity. If no phenomenon possesses an independent essence, then the distinctions between helper and helped, subject and object, liberator and liberated, begin to dissolve. Thus, the bodhisattva becomes “one who sees no beings to save”, not out of apathy or denial, but because their wisdom reveals the illusory separateness at the root of suffering. Compassion, in this light, is not sentimental charity but the natural expression of non-duality: the spontaneous, boundaryless responsiveness to suffering wherever it appears.

This vision finds rich philosophical articulation in the Madhyamaka school, particularly in the work of Nāgārjuna, who argued that all concepts, including even nirvana and saṃsāra, are empty of self-nature (svabhāva). From this view, the bodhisattva does not cling to enlightenment as a personal achievement nor reject saṃsāra as inherently flawed, but remains open and responsive within the flow of conditions.

Yogācāra thought adds another layer, emphasizing the constructed nature of experience through the workings of mind. In this model, the bodhisattva recognizes that all phenomena arise from mind and thus cultivates a purified, compassionate cognition free from dualistic error. The world is not passively observed but actively shaped by consciousness. A vision that encourages responsibility, clarity, and transformation from within.

In both schools, the bodhisattva is not merely someone who postpones nirvana, but one who has gone beyond fixed notions of nirvana and delusion alike. Their freedom is not escape, but participation. It is not a transcendence that leaves the world behind, but one that re-engages the world with unshakeable compassion and unbounded vision.

Critique and integration

A persistent critique voiced by Mahāyāna sources is that the Arhat ideal, as emphasized in early Buddhism, represents a narrow or self-centered goal, one focused on individual liberation rather than collective awakening. From the Mahāyāna perspective, the Arhat may be seen as one who turns away from the world after achieving personal freedom, thus neglecting the deep interdependence of all beings. However, this critique should be approached with nuance.

Early Buddhist texts do not portray the Arhat as egoistic or indifferent. The Arhat is one who has eradicated the very basis of selfishness, craving and delusion, and acts from a deep clarity and inner peace. The Mahāyāna reinterpretation, then, does not necessarily negate this image, but reframes it by emphasizing the bodhisattva’s embrace of infinite responsibility, even in the absence of a fixed self. The contrast is more one of emphasis than of contradiction: a solitary liberation versus an ongoing, collective liberation in service of others.

This tension between the paths of the Arhat and the bodhisattva gave rise to extensive doctrinal and philosophical dialogues within the Buddhist tradition. Later schools, especially those influenced by Madhyamaka and Yogācāra thought, sought to integrate these views by showing that the Arhat’s realization of non-self could naturally evolve into the bodhisattva’s vow to remain in the world. In this light, the bodhisattva path is not a rejection of early Buddhist insight but its expansion. A turning of wisdom outward, into boundless compassion.

In modern contexts, this expansive view has inspired movements such as Engaged Buddhism, which brings the bodhisattva ideal into the realms of social justice, environmental activism, and interfaith dialogue. Here, the bodhisattva is not only a religious ideal, but a call to ethical responsibility in the face of systemic suffering. Contemporary interpretations no longer frame the bodhisattva as an esoteric being in scriptures, but as any individual willing to act for the liberation of others with courage, humility, and perseverance.

Thus, the bodhisattva ideal continues to evolve, not as a fixed identity, but as an open, responsive practice that bridges the ancient and the present, the solitary and the communal, the contemplative and the engaged.

The following table summarizes the differences between the Arhat and the bodhisattva:

| Aspect | Arhat | Bodhisattva |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation | Seeks personal liberation from saṃsāra | Seeks universal liberation for all beings |

| Goal | nirvana as end of rebirth and suffering | Awakening postponed to help others; nirvana redefined as compassionate presence |

| Practice | Emphasis on detachment and personal discipline | Emphasis on compassion, wisdom, and altruistic vows |

| Ethics | Ethical clarity arising spontaneously from cessation of illusion; compassion, equanimity, and all brahmavihāras emerge naturally in the Arhat, not by following prescribed rules. The Arhat is “auto-ethical,” acting from wisdom free of self-reference. | Ethical action rooted in interdependence and non-duality |

| View of saṃsāra | Something to escape | A field of compassionate engagement |

| rebirth | To be overcome | Willingly accepted as a means to aid others |

| Symbolic ideal | The liberated sage | The compassionate hero |

Conclusion

The bodhisattva stands at the heart of Mahāyāna Buddhism as a transformative model of awakened compassion — one who not only realizes the emptiness of self and phenomena, but channels that realization into sustained, altruistic engagement with the world. The historical emergence and philosophical depth of the bodhisattva ideal reveal a transformation in Buddhist soteriology: liberation is no longer framed primarily as withdrawal from suffering, but as compassionate participation in it. Doctrinally, the bodhisattva path affirms the union of wisdom and compassion as its foundation; psychologically, it transforms motivation and perception through the generation of bodhicitta; and philosophically, it reconceives the very nature of liberation as non-dual participation in the world. These dimensions distinguish the bodhisattva’s path from that of the Arhat, not by contradiction, but by scope and orientation. While the Arhat seeks final release from saṃsāra through the cessation of karmic activity, the bodhisattva voluntarily remains, embodying a different kind of liberation: one that sees no ultimate distinction between nirvana and the world of suffering.

A central theme has been the role of bodhicitta, the awakened resolve to benefit all beings, which functions not as a sentimental wish but as the structural foundation of the bodhisattva’s practice. It enables the bodhisattva to act freely and compassionately without being caught in the feedback loop of karma and self. This framework redefines ethical life, not as rule-following, but as a natural expression of insight into interdependence and non-duality.

Critically, while Mahāyāna texts sometimes contrast the bodhisattva path with that of the Arhat, this tension need not be seen as doctrinal opposition. Instead, it may reflect a shift in emphasis: from individual liberation to collective responsiveness; from detachment to relational action. Both paths affirm the possibility of freedom from delusion and suffering, but they differ in their vision of how this freedom is lived out.

In contemporary contexts, the bodhisattva ideal remains relevant precisely because it is not confined to religious identity or institutional Buddhism. It offers a framework for ethical orientation that resonates with modern concerns such as climate crisis, social injustice, and the fragmentation of community. The bodhisattva does not retreat from such challenges but meets them as fields of practice, where wisdom and compassion are actualized in real time.

In this sense, the bodhisattva is not a perfected being beyond reach, but a dynamic process of becoming: one who continually reaffirms their commitment to others in light of changing conditions. Far from representing moral perfectionism or self-sacrifice, the bodhisattva ideal points toward a deeply pragmatic vision: that the path of awakening is inseparable from how we live, act, and relate to others in a world marked by impermanence and interdependence.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments