Early Buddhist monasteries

The emergence of Buddhist monasteries marks a turning point in the history of Buddhism, transforming a loosely organized community of wandering ascetics into a structured and enduring institution. These early monasteries, known as vihāras, served as physical centers for spiritual cultivation, doctrinal preservation, and social organization. Drawing on textual sources, archaeological evidence, and historical context, in this post we examine the origins, architecture, organization, and geographic spread of the first Buddhist monasteries, with attention to their role in shaping the evolution of Buddhism over time.

Remains of the Jetavana monastery, Sāvatthī, India. The Jetavana monastery was one of the most important monastic complexes in early Buddhism, founded by the wealthy merchant Anāthapiṇḍika. It became a major center for the Siddhartha’s teachings and a model for later monastic establishments. The site is known for its large stūpa, monastic cells, and assembly halls, reflecting the architectural evolution of Buddhist monasteries. The monastery played a crucial role in the development of monastic life and community organization in early Buddhism. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Introduction

A Buddhist monastery, traditionally referred to as a vihāra, is a residential and institutional complex established to support the communal life of ordained monks (bhikkhus) and nuns (bhikkhunīs). In the earliest phase of Buddhism, the vihāra emerged as more than just a shelter. It was a place for meditation, study, teaching, and ritual, embodying the collective pursuit of the path toward liberation. The term originally referred to a “dwelling” or “retreat”, and over time it came to signify a structured religious community centered around the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama.

The monastic institution lies at the heart of Buddhism. Unlike the solitary renunciant ideal found in some religious traditions, early Buddhism envisioned the saṅgha, the community of practitioners, as an essential pillar alongside the Buddha and the Dharma. Monasteries provided a physical and social framework in which the saṅgha could live according to the Vinaya (monastic code), transmit teachings, and interact with lay communities.

Historically, the establishment of monasteries reflects both doctrinal developments and changing socio-political contexts. Initially shaped by the need for temporary refuge during the rainy season, these spaces evolved into year-round centers of spiritual and intellectual activity. They were often founded through lay or royal patronage and became hubs for the preservation and dissemination of Buddhist teachings, making the vihāra one of the most influential institutions in the history of Buddhism.

Origins in the time of Siddhartha Gautama

The origins of the Buddhist monastery can be traced to the time of Siddhartha Gautama, when the early saṅgha adopted a mobile, mendicant lifestyle in accordance with ascetic ideals. However, a key moment in the institutionalization of monastic life came with the practice of the annual vassa, a three-month rainy season retreat observed across much of the Indian subcontinent. During this period, monks and nuns were expected to cease their wandering and reside in a single location, both to minimize harm to crops and insects and to create conditions conducive to intensive practice. This temporary but regular anchoring of the saṅgha laid the foundation for the development of more permanent shelters.

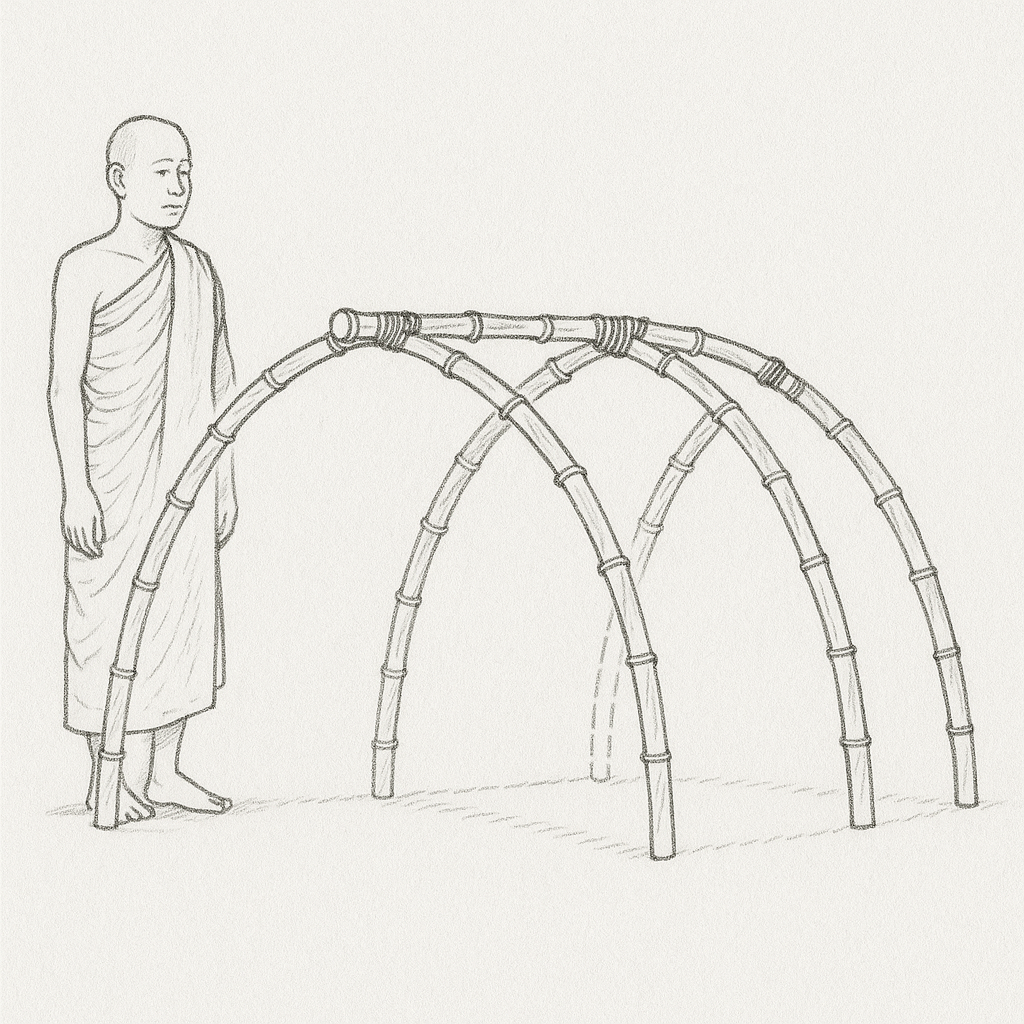

Sketch of an early Buddhist monk’s hut. The earliest monastic shelters were rudimentary structures reflecting the ascetic lifestyle of the early saṅgha. A few sticks stuck into the ground at both ends and connected by longitudinal struts formed the simple skeletal frame of the hut, which each bhikkhu constructed for himself at the beginning of the monsoon season and dismantled afterwards. Built from natural materials and designed for easy assembly and disassembly, these huts emphasized functionality and minimalism, in keeping with the principles of renunciation and detachment from material possessions. The image was generated by DALL·E 2 based on a figure in Hans Wolfgang Schumann, Der historische Buddha: Leben und Lehre des Gotama (2004).

Initially, these dwellings were rudimentary: simple huts made from wood, bamboo, and thatch, often constructed by the monastics themselves at the edge of forests or near villages. Over time, as the number of ordained followers grew and lay support increased, these impermanent structures gave way to more enduring establishments. The earliest historically attested monasteries were not constructed by monks but were gifted by devoted patrons. Notable among them is the Jetavana monastery, donated by the wealthy merchant Anāthapiṇḍika near Sāvatthī, and the Veluvana monastery, granted by King Bimbisāra near Rājagaha. These institutions offered accommodations, teaching halls, and communal spaces, effectively formalizing the Buddhist monastic community.

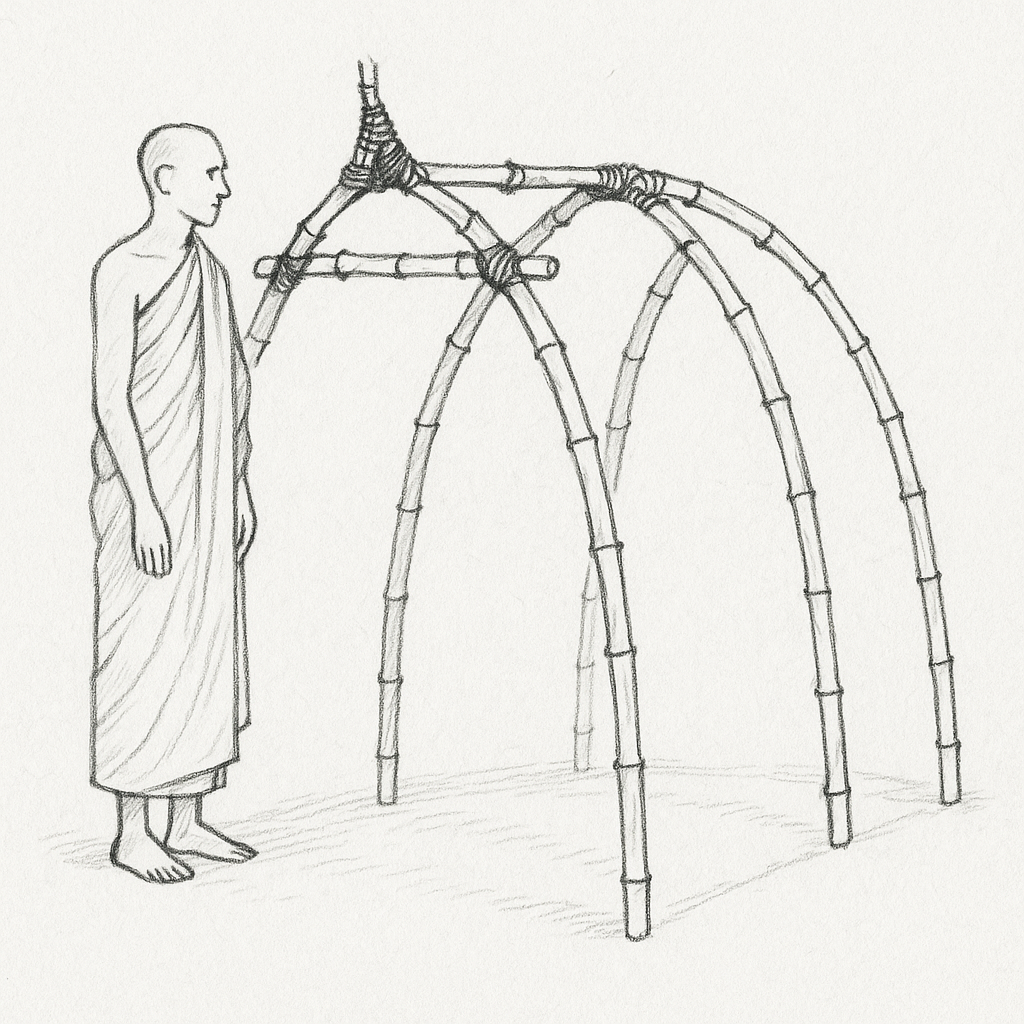

Sketch of the further development of early Buddhist monk’s huts. As the saṅgha became more established and lay devotees began to play a greater role in its support, larger huts were constructed from the same natural materials as earlier shelters. These structures, built by lay followers, allowed for upright standing and introduced architectural features that would come to define early Buddhist building traditions — including pointed gable entrances, barrel vault roofs, and rounded apses. This characteristic style, initially realized in perishable materials, was later reproduced using timber beams, laying the foundation for the development of Buddhist architecture across South and Southeast Asia. The image was generated by DALL·E 2 based on a figure in Hans Wolfgang Schumann, Der historische Buddha: Leben und Lehre des Gotama (2004).

The involvement of lay supporters and royalty was instrumental in this process. The gifting of land and facilities to the saṅgha was seen as a meritorious act, and the support of prominent figures gave monastic establishments both material stability and public legitimacy. Thus, from its early reliance on seasonal shelters, the Buddhist monastic tradition quickly evolved into a network of fixed institutions supported by a reciprocal relationship between the saṅgha and its lay patrons.

A hall of of the Ellora cage temple (cave 10) with bell-shaped stupa in the apse. The Ellora caves, located in Maharashtra, India, are a UNESCO World Heritage Site and showcase the architectural evolution of Buddhist monastic complexes. The caves were excavated between the 5th and 8th centuries CE and feature intricate rock-cut architecture, including monastic cells, prayer halls, and stupas. The site reflects the influence of various dynasties and the integration of Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain traditions. The caves served as important centers for meditation, study, and community life for monks and lay followers alike. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Structural and functional features

The earliest Buddhist monasteries were modest in their architectural form, reflecting the ascetic ethos of the saṅgha and the material limitations of their environment. They were often built using bamboo, thatch, and wooden poles, allowing for easy construction, dismantling, and adaptation to the forested or semi-rural settings in which the early saṅgha lived. These materials, while impermanent, facilitated the construction of shelters that met the practical needs of monastics during the vassa season and beyond.

As monastic life became more permanent and patronage increased, the design of vihāras evolved into more organized and multifunctional spaces. A typical monastery came to include individual cells (kutikās) for private meditation and rest, open courtyards to promote ventilation and provide communal gathering space, and central meeting halls (uposatha-gāra) used for collective recitation of the monastic code, instruction, and rituals. Some also included storage rooms, kitchen areas, and spaces for visitors and novices.

The architecture of these monasteries was explicitly tied to their functional roles. The design promoted a daily rhythm of meditation, instruction, and communal interaction, guided by the Vinaya rules. Individual practice was balanced by structured communal life, including shared meals, ceremonial observances, and teaching sessions. The spatial layout was thus both practical and symbolic — supporting the goal of personal liberation through collective discipline.

Over time, monasteries transitioned from temporary shelters into institutionalized communities. The increasing complexity of layout and administration reflected not only the growth in the number of residents but also the monastery’s expanding role as a hub for education, scriptural preservation, and lay interaction. This transformation marked a foundational moment in the development of Buddhist institutional life, setting a precedent for future architectural and organizational models across the Buddhist world.

Archaeological evidence

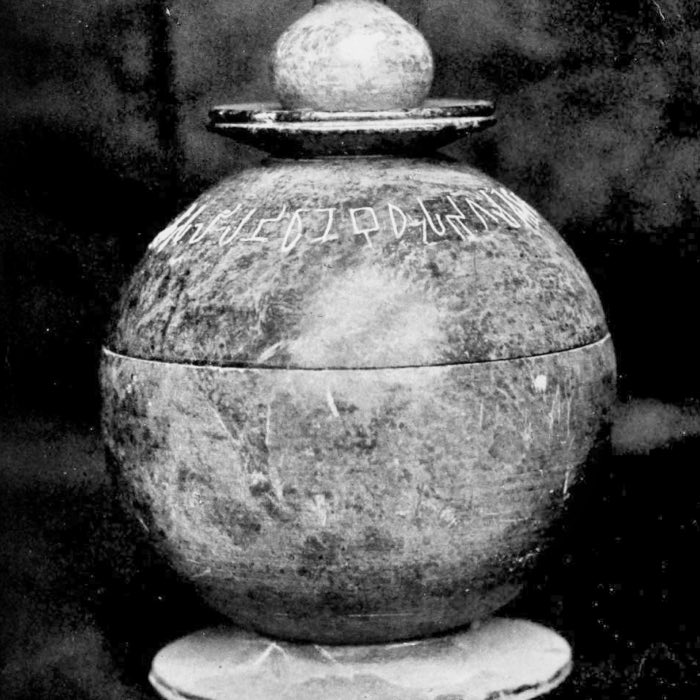

Archaeological discoveries have played a crucial role in illuminating the early development of Buddhist monasticism. Sites such as Piprahwa, Bhārhut, Sanchi, and Nālandā offer physical evidence of the transition from temporary monastic shelters to permanent, architecturally sophisticated institutions. At Piprahwa in present-day Uttar Pradesh, excavations revealed a large stūpa structure and relic caskets with inscriptions that some scholars associate with the Śākya clan and early Buddhist communities. Though the interpretation remains debated, the site provides important data on monastic patronage and funerary practices.

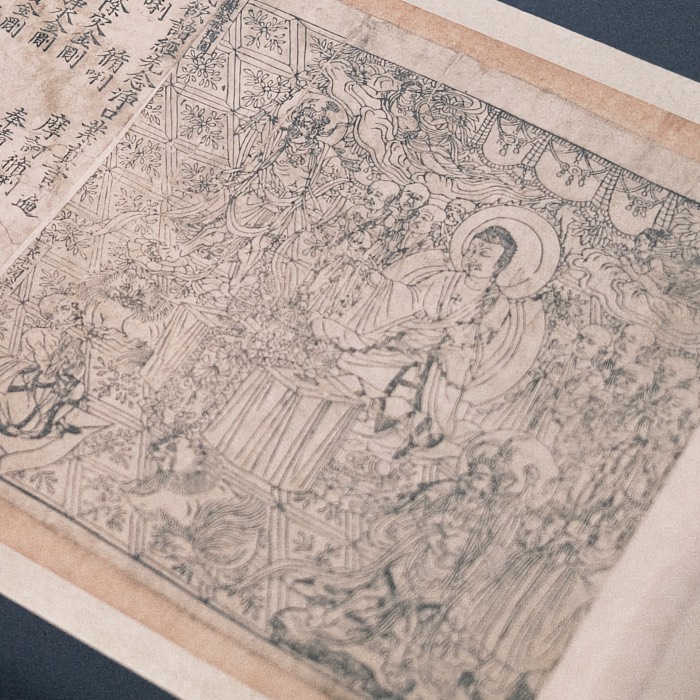

The Bhārhut and Sanchi complexes, dating from the 2nd century BCE, offer evidence of monasteries adjacent to large stūpas. These sites demonstrate how the monastic and devotional dimensions of Buddhism were spatially integrated. In particular, Bhārhut’s numerous inscriptions reveal the names of donors — monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen — showing that the construction and maintenance of monastic spaces was a community effort.

Stupas and monasteries at Sanchi in the early centuries of the Common Era. Reconstruction, 1900. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Nālandā, which flourished from the 5th century CE onward, represents a later but more institutionalized phase of Buddhist monasticism. Its remains include multi-storey residential compounds, lecture halls, and libraries, offering insight into the evolution of monasteries into centers of advanced learning and international religious exchange.

Ruins of the Nalanda Buddhist University, which flourished from 427 to 1197 CE, Nalanda, Bihar, India. The site is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and was one of the world’s first residential universities. It attracted scholars from various regions, including China, Korea, Japan, Tibet, Mongolia, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia. The university was known for its rigorous academic curriculum and its emphasis on logic and philosophy. The ruins include stupas, monasteries, temples, and a large number of votive stupas. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Across these and other sites, the presence of relics, inscribed votive tablets, and dedicatory inscriptions provides not only religious context but also valuable chronological and social information. These artifacts illustrate how early monastic institutions were closely tied to lay patronage, ritual practices, and evolving conceptions of sacred space. The shift from perishable materials like wood and bamboo to durable brick and stone construction marks an important architectural turning point, ensuring the physical endurance of these early monastic foundations and leaving a lasting legacy for historical and archaeological study.

Monastic discipline and organization

The early Buddhist monastic community was governed by a comprehensive framework of rules and procedures codified in the Vinaya Piṭaka, one of the three principal divisions of the Tipiṭaka. The Vinaya outlines the ethical precepts, daily routines, conflict resolution mechanisms, and disciplinary codes that structured the life of monks and nuns. It evolved in response to real situations faced by the early saṅgha and was systematically preserved through oral transmission before being committed to writing. The aim of the Vinaya was not merely to regulate behavior, but to foster communal harmony, support spiritual discipline, and uphold the integrity of the monastic institution.

The organizational structure of the saṅgha was based on principles of seniority, consensus, and ordination lineage. Entry into the monastic order required formal ordination (upasampadā), and senior monks (theras) held authority in guiding junior members. Decision-making followed collective procedures, particularly during the fortnightly uposatha ceremonies, when the community gathered to recite the monastic rules and confess any transgressions. While the early saṅgha emphasized egalitarianism in principle, functional hierarchies developed to manage monastic affairs and preserve doctrinal continuity.

Economically, monasteries relied on alms, donations, and eventually land grants to sustain their operations. In the earliest phase, monks and nuns subsisted through daily alms rounds (piṇḍapāta), emphasizing their dependence on the lay community. As monastic settlements became more permanent and influential, they attracted the support of kings, merchants, and lay devotees. Donations took various forms — food, robes, medicine, and later, land and building materials. Some monasteries acquired agricultural land, the income from which funded the maintenance of resident monks and supported religious activities. While this economic support enabled the flourishing of Buddhist institutions, it also introduced new administrative and ethical challenges, which the Vinaya sought to address through rules on property, dependency, and communal use.

Together, the Vinaya, ordination system, and economic model laid the foundation for a durable monastic framework — flexible enough to adapt to changing conditions, yet structured enough to preserve continuity across time and regions.

Spread and institutionalization

The spread of Buddhist monasteries beyond their Indian heartland was closely tied to both missionary efforts and the increasing institutionalization of the saṅgha. One of the earliest and most significant phases of this expansion occurred during the reign of Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE. Following his conversion to Buddhism, Ashoka became a powerful patron of the monastic community, sponsoring the construction of numerous monasteries and stūpas throughout his empire. He also played a central role in the dispatch of missionary missions to regions such as Sri Lanka, Gandhāra, Central Asia, and beyond, often accompanying these missions with gifts of sacred texts, relics, and architectural expertise.

In Sri Lanka, the arrival of Mahinda, Ashoka’s son or close associate, is traditionally credited with the establishment of the first monastery at Mahāvihāra in Anurādhapura. This site became a major center of Theravāda Buddhism and a model for monastic organization in the island and across the southern Buddhist world. The durability of Sri Lankan monasteries and their ongoing use into the modern era testify to the success of these early foundations.

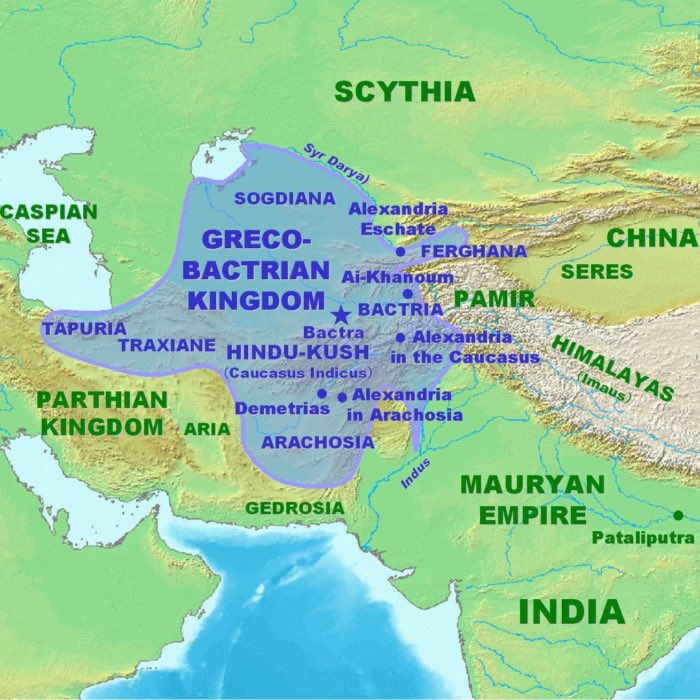

In Central Asia, Buddhist monasticism spread along the trade routes of the Silk Road, facilitated by merchants, itinerant monks, and the needs of travelers seeking rest and religious merit. Monasteries were established in oasis towns and became cultural hubs where Indian, Iranian, Hellenistic, and Chinese influences intersected. These institutions played a pivotal role in transmitting not only the Dharma but also Buddhist art, iconography, and literary traditions to East Asia.

As Buddhism spread geographically, the monastic model proved highly adaptable. Vihāras were established in new environments and often absorbed local architectural styles and social customs while maintaining core features of discipline and communal life. These monasteries served as transnational nodes of Buddhist knowledge, training centers for monks, repositories of scriptures, and agents of cultural continuity across a vast and diverse Buddhist world.

Conclusion

The development of early Buddhist monasteries reflects a process of institutional consolidation that began during the lifetime of Siddhartha Gautama and expanded significantly in the centuries that followed. Initially established as seasonal shelters for mendicant monks, these early vihāras evolved into permanent centers for religious practice, education, and community life. Their architecture and internal organization were shaped by both doctrinal imperatives and the practical needs of communal living.

These monastic foundations played a pivotal role in the preservation and dissemination of the Buddha’s teachings. They provided the saṅgha with a stable framework for training, administration, and interaction with lay society. As Buddhism spread beyond India, the monastic model proved resilient and adaptable, influencing a wide range of architectural and institutional forms across South, Central, and East Asia.

In historical terms, the vihāra stands as one of Buddhism’s most enduring contributions to religious infrastructure. Its core functions — meditation, instruction, discipline, and community — formed the backbone of Buddhist practice and enabled the religion’s sustained development over two millennia. The study of early monasteries thus provides essential insight into the formative structures that supported Buddhism’s growth as both a spiritual path and a social institution.

References and further reading

- Hans Wolfgang Schumann, Der historische Buddha: Leben und Lehre des Gotama, 2004, Diederichs, ISBN: 9783896314390

- Trainor, Kevin, Relics, Ritual, and Representation in Buddhism: Rematerializing the Sri Lankan Theravāda Tradition, 1997, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521582803

- Hirakawa, Akira, A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna, 2018, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN: 978-8120809550

- Schopen, Gregory, Buddhist Monks and Business Matters: Still More Papers on Monastic Buddhism in India, 2004, University of Hawai‘i Press, ISBN: 978-0824827748

- Heitzman, James, Gifts of Power: Lordship in an Early Indian State, 1997, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195639780

- Dutt, Sukumar, Buddhist Monks and Monasteries of India: Their History and Contribution to Indian Culture, 1989, Motilal Banarsidass Publications, ISBN: 978-8120804982

- Gombrich, Richard, Theravāda Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo, 2006, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415365093

- Warder, A. K., Indian Buddhism, 2000, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120817418

- Coningham, Robin & Ruth Young, The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE–200 CE, 2023, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521609722

comments