Buddhist cave temples

Buddhist cave temples and monasteries are among the most remarkable architectural and religious achievements in the history of Buddhism. Carved into cliffs and mountains across Asia, these sites served both as places of worship and as monastic residences, reflecting a complex interplay of spiritual practice, artistic expression, and cultural exchange. From India to China, from Central Asia to Southeast Asia, these rock-cut complexes provide critical insight into the development of Buddhist institutions, the transmission of the Dharma, and the regional adaptations of sacred space.

The Carpenter’s cave (Buddhist Cave 10), Ellora Caves, Maharashtra, India. 600–1000 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Introduction

Cave temples and cave monasteries represent some of the earliest and most enduring expressions of Buddhist sacred architecture. While the terms are often used interchangeably, a distinction can be drawn between the two: cave temples typically refer to spaces primarily designated for ritual worship, housing images of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas, stupas, and chaitya halls; cave monasteries (vihāras), by contrast, were designed as residential and communal spaces for monks, including meditation cells, refectories, and teaching halls. Many cave complexes integrate both functions, reflecting the holistic vision of Buddhist monastic life where spiritual practice, study, and ritual coexisted.

These carved sanctuaries are not only religious sites but also important cultural and historical repositories. They encapsulate centuries of artistic development, reflect evolving doctrinal concerns, and often record the names and aspirations of their patrons through inscriptions. Their creation, often involving the laborious excavation of solid rock, symbolizes both spiritual dedication and the institutional strength of the saṅgha across different periods and regions.

Cave monasteries emerged directly from the ascetic ideals that shaped the early Buddhist community. The forest-dwelling tradition, where renunciants sought solitude for meditation and simplicity in lifestyle, informed the selection of caves as ideal dwellings — natural, remote, and conducive to contemplation. Over time, these informal refuges evolved into architecturally sophisticated complexes supported by lay devotion and royal patronage, allowing Buddhism to root itself both physically and institutionally in the landscape.

Origins and early development

Cave temples and monasteries have a long history in the Indian subcontinent, with their origins tracing back to the early centuries of Buddhism. The development of these rock-cut structures was influenced by various factors, including the ascetic practices of early Buddhists, the patronage of local rulers and wealthy merchants, and the need for communal spaces for worship and meditation.

Roots in pre-Buddhist rock-cut architecture and early monastic shelters

The tradition of cave architecture in Buddhism can be traced not only to pre-Buddhist rock-cut sanctuaries but also to the humble origins of the Buddhist monastic community. In the earliest phase, monks of Siddhartha Gautama’s saṅgha built simple huts from wooden sticks — pairs of poles planted into the ground and connected with horizontal crossbars — used during the rainy season (vassa) and dismantled afterward. These makeshift dwellings, later supported by lay patrons, gradually evolved into more stable structures allowing upright posture and communal use. This gave rise to an early Buddhist architectural idiom characterized by peaked gables, barrel roofs, and rounded apses — features that later influenced cave temple design.

Western Indian rock-cut caves, such as those at Bhaja, replicate in stone this timber-framed style. The apex of the chaitya arch, for example, preserves the visual memory of bamboo constructions from early monastic architecture. The cave at Bhaja, carved in the 2nd century BCE and used until the 6th century CE, is a notable example of how rock-cut forms preserved the aesthetic and structural heritage of ephemeral monastic shelters.

Early Buddhist cave sanctuaries in India

The earliest Buddhist cave sanctuaries in India emerged around the 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE, often under the patronage of merchants and early ruling elites sympathetic to the Dharma. Among the oldest are the caves at Barabar Hills in Bihar, associated with the Mauryan emperor Ashoka and the Ajivikas, which set a precedent in polishing and carving technique. These early sanctuaries typically included chaitya halls, spaces for congregational worship, and vihāras, which served as monastic dwellings. Their architecture was highly symbolic, incorporating wooden prototypes into stone and creating enduring spaces for devotional practice and monastic discipline.

Patronage and the shift from temporary shelters to permanent monastic complexes

This architectural transformation was closely tied to the increasing support of the Buddhist saṅgha by wealthy patrons and political authorities. Initially, monastic life was characterized by simplicity and mobility, especially during the rainy season when monks temporarily settled in makeshift huts. However, as Buddhism grew in popularity and the saṅgha became more institutionally established, lay donors began to sponsor the excavation of permanent cave complexes. These donations were motivated by religious devotion, social prestige, and the merit-generating potential of supporting the saṅgha. As a result, early rock-cut caves began to take on more elaborate and enduring forms — complexes such as those at Karla, Bedsa, and Nasik illustrate this shift, featuring grand facades, intricately carved pillars, and integrated worship and residential areas. These developments mark the beginning of a monumental tradition that would continue to evolve and spread throughout Asia.

Architectural features and functions

The architectural features of Buddhist cave temples and monasteries are characterized by their rock-cut construction, which allowed for the creation of vast, intricate spaces within solid rock. The design and layout of these caves reflect both functional needs and spiritual ideals, with a focus on creating environments conducive to meditation, worship, and communal living.

Layout and spatial organization

Buddhist cave complexes exhibit a careful and purposeful organization of space that reflects both functional needs and spiritual ideals. The most iconic architectural components are the chaitya halls, elongated, apsidal-ended spaces designed for congregational worship centered on a stūpa, and the vihāras, which served as the monastic residences. Vihāras typically contain a central hall surrounded by individual meditation cells cut into the rock walls, allowing each monk a private space for practice and rest.

Over time, these basic units evolved into larger, more complex layouts. Many caves feature assembly halls, shrines, and ritual platforms, indicating communal and ceremonial functions. Stūpas, either sculpted or freestanding, are often found at focal points in both chaitya halls and residential areas, functioning as objects of veneration and reminders of the Buddha’s presence. The use of space also reflects a rhythm between solitude and community, with secluded cells supporting meditative retreat and open halls enabling teaching, chanting, and devotional gatherings.

Artistic elements

The artistic embellishment of cave temples reveals the depth of Buddhist cosmology, narrative, and iconography. Rock surfaces were transformed into elaborate sculptural programs, with carvings depicting seated and standing Buddhas, Bodhisattvas in princely attire, and guardian figures flanking entrances or protecting sacred spaces. These images were not merely decorative, they were integral to the devotional life of the monastic community and visiting lay pilgrims.

In addition to sculpture, many cave sites, particularly Ajanta and Mogao, feature extensive mural paintings that recount the Jātaka tales, scenes from the Buddha’s life, and celestial motifs. These murals served both didactic and aesthetic functions, educating viewers in the Dharma while creating immersive, sacred environments. The narrative sequencing of panels and the positioning of figures reinforced specific teachings or ritual pathways.

A distinctive hallmark of Buddhist cave art is its integration with the natural rock. Rather than concealing the material, artists and architects emphasized its texture and contours, allowing the spiritual message to emerge from the living mountain itself. This synthesis of architecture and environment underscored the Buddhist principle of harmony between the human and the natural, the transient and the eternal.

Regional variations

The spread of Buddhism across Asia led to the emergence of diverse cave temple traditions, each reflecting local cultural, artistic, and religious contexts. While the fundamental architectural forms remained consistent, regional adaptations resulted in unique expressions of Buddhist devotion and aesthetics.

India

is the birthplace of Buddhist cave architecture, and it is home to some of the most iconic and earliest examples. Sites such as Ajanta, Ellora, Bhaja, and Karla showcase the evolution from simple rock-cut shelters to elaborate artistic and ritual complexes. The Satavahana dynasty (2nd century BCE to 3rd century CE) played a vital role in the development of cave sanctuaries, particularly in western India, funding early chaitya halls and vihāras. The Gupta period (4th–6th centuries CE) brought refined sculptural styles, more anthropomorphic images of the Buddha, and a greater integration of narrative panels. Dynastic patronage continued through the later periods, including under the Rashtrakutas and Chalukyas, who expanded these complexes into multi-level marvels blending devotion, art, and engineering.

Ajanta Cave 26, Chaitya Hall (or prayer hall). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Ajanta Cave 1, monastery (vihara) with a seating Buddha statue.Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Ellora Caves 11 and 12 are three-storey monasteries cut out of a rock, with Vajrayana iconography inside. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Bhaja cave monastery. Directly next to the main hall (chaitya) is a two-storey residential cave (vihara). The chaitya hall was originally enclosed by a wooden façade with integrated window and door openings. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Bhaja caves, plan (1880). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Great Chaitya in the Karla Caves, Maharashtra, built in 50-70 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Karla Caves, Pillar at entry of main chaitya. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Karla Caves, the Great Chaitya section in perspective (1955). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Central Asia and Afghanistan

The caves of Bamiyan in Afghanistan, now tragically damaged, once housed monumental Buddha statues and intricate mural cycles that reflected a unique confluence of Indian, Hellenistic, Persian, and Central Asian artistic elements. Situated along the Silk Road, Bamiyan and other Central Asian cave sites served as key nodes in the transmission of Buddhism across Eurasia. The region’s cave architecture often emphasized the grandeur of the Buddha image, representing the universalizing ambitions of Mahāyāna Buddhism in a multi-ethnic, transregional context.

Bamiyan in Afghanistan, taller, 55 meter Buddha in 1963 and in 2008 after destruction. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

China

In China, cave temples took root and flourished with striking regional adaptations. The Mogao caves at Dunhuang, Yungang, and Longmen are monumental projects carved between the 4th and 9th centuries CE. These sites reflect the integration of Indian Buddhist iconography with Chinese aesthetics, Confucian ethical narratives, and Daoist cosmology. The Mogao caves, in particular, became repositories of Buddhist art and manuscripts, serving both as sacred spaces and cultural libraries. The iconography, painted mandalas, and sculptural innovations at these sites demonstrate a deeply localized form of Buddhist devotion and artistic refinement.

Sculpture and murals from Mogao cave nb. 254, built during the Northern Wei period between 475 and 490 CE. It is one of the earliest caves in Dunhuang, and shows parallels with the Kizil Caves, Western Indic features and Western influences. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

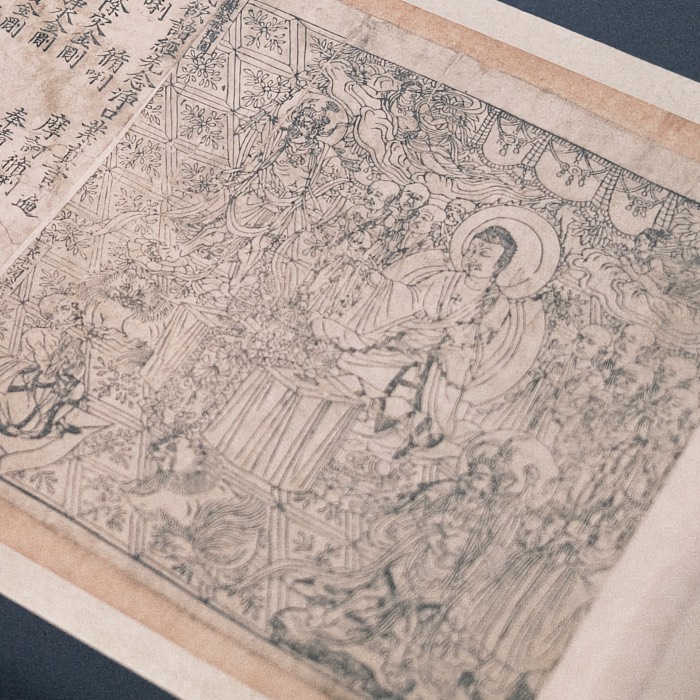

The “Library Cave”: Picture of Cave 16, by Aurel Stein in 1907, with manuscripts piled up beside the entrance to Cave 17 (the Library Cave, which is to the right in this picture). In 1906, Stein discovered a large cache of manuscripts in this cave, which had been sealed up for centuries. The manuscripts were written in various languages, including Chinese, Tibetan, and Sanskrit. The discovery of the manuscripts was a major archaeological find and has provided valuable insights into the history of Buddhism in China and Central Asia. Among the manuscripts were Buddhist texts, including sutras and commentaries, as well as secular texts, such as poetry and history. Also, the oldest known printed book, the Diamond Sutra, was found in this cave. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Yungang Grottos, located in Shanxi province, are another significant example of early Chinese cave temples. Carved during the Northern Wei dynasty (386–535 CE), these caves feature large-scale sculptures and intricate reliefs that reflect a blend of Indian and Central Asian influences. The Yungang caves are notable for their monumental Buddha figures (as shown here, cave 7) and elaborate iconography, showcasing the syncretic nature of early Chinese Buddhism. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Yungang Grottos, Cave 12, decorative stucco reliefs with Buddhas, musicians, and apsarasas. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Lu She Na Buddha at the Longmen Grottoes, Henan province, China. The Longmen Grottoes, carved between the 5th and 12th centuries CE, are renowned for their intricate sculptures and inscriptions. The caves feature thousands of Buddhist statues, including the famous Lu She Na Buddha, which stands at over 17 meters tall. The Longmen Grottoes reflect the artistic and cultural exchange between India and China during the Tang dynasty. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Massive Buddhist sculptures in the main grotto of Longmen. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Korea and Japan

In Korea, cave temples such as Seokguram exemplify the synthesis of Indian stylistic elements with Korean granite craftsmanship and spiritual expression. Built in the 8th century CE during the Unified Silla period, Seokguram houses a sublime seated Buddha surrounded by Bodhisattvas, arhats, and guardians, arranged in a carefully calculated architectural mandala. In Japan, while natural cave sanctuaries are rarer, early Buddhist transmission included the carving of Kannon images into cliffs and rock walls, indicating the adaptation of cave worship to new cultural landscapes. These adaptations reveal the evolving aesthetic and ritual dimensions of Buddhism as it spread into East Asia.

The central Buddha statue at Seokguram, Korea. Seokguram is a UNESCO World Heritage site and is considered one of the finest examples of Buddhist art in East Asia. The cave temple features a large granite Buddha statue, surrounded by Bodhisattvas and other figures, all intricately carved into the rock. The design of Seokguram reflects the influence of Indian and Central Asian Buddhist art, while also showcasing the unique aesthetic sensibilities of Korean artisans. The cave’s location on Mount Tohamsan adds to its spiritual significance, as it is believed to be a sacred site for both Buddhism and Shamanism. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: Korea Open Government License Type I: Attribution)

Southeast Asia

In Sri Lanka, the Dambulla cave temple complex is a major site of continuous Buddhist worship, featuring over a hundred statues and vivid ceiling paintings that span centuries. In Myanmar, the Pindaya caves house thousands of small Buddha images installed by pilgrims over generations, creating a densely devotional atmosphere. In Thailand and Laos, natural caves were often appropriated for monastic retreat and localized cultic practices, blending Theravāda orthodoxy with indigenous beliefs. These sanctuaries emphasize a devotional intimacy, where the cave becomes both a sheltering space and a sacred womb for spiritual transformation.

Stupa with sitting Buddhas around it, in the Dambulla complex of cave monasteries. Sri Lanka. The Dambulla cave temple complex is a UNESCO World Heritage site and is one of the largest and best-preserved cave temple complexes in Sri Lanka. The caves contain numerous statues and paintings depicting the life of the Buddha, as well as various Bodhisattvas and deities. The site has been a place of pilgrimage for centuries and continues to be an important center of Buddhist worship. The caves are also known for their stunning rock formations and natural beauty, making them a popular tourist destination. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Dambulla cave temple complex, Sri Lanka, statue of sleeping Buddha inside a cave. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Interior of the Pindaya Caves, Myanmar. The Pindaya caves are a series of limestone caves located in the Shan State of Myanmar. They are famous for their thousands of Buddha statues, which have been placed there by pilgrims over the years. The caves are also home to various religious artifacts and paintings, making them an important pilgrimage site for Buddhists. The Pindaya caves are set in a picturesque location, surrounded by lush hills and scenic views, attracting both religious devotees and tourists alike. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Religious and social functions

Buddhist cave temples and monasteries served as vital centers for both spiritual cultivation and social engagement. Their secluded locations and thoughtfully designed interiors provided ideal settings for meditation, study, and communal monastic life. Individual rock-cut cells offered spaces for solitary practice and mindfulness, while larger halls and open areas supported scriptural study, chanting, and ritual activity. These cave complexes functioned not only as places of retreat but as enduring homes for entire monastic communities, fostering a rhythm of daily discipline embedded in a sacred architectural context.

At the same time, these sites functioned as prominent places of pilgrimage and lay devotion. Pilgrims traveled long distances to visit renowned caves, venerate sacred images and relics, and gain spiritual merit through offerings and prayers. The presence of inscriptions bearing the names of donors, from kings and merchants to humble villagers, attests to the broad spectrum of patronage these spaces received. The act of supporting a cave sanctuary was regarded as an expression of piety and a means of accruing puṇya (merit), thereby integrating monastic institutions into the broader social and economic life of their communities.

Cave sanctuaries also played a critical role in the transmission and visual expression of Buddhist teachings. Through their sculptural programs and mural paintings, they served as three-dimensional scriptures, making complex doctrines and narrative cycles accessible to both literate and non-literate audiences. These artistic representations reinforced key themes of impermanence, compassion, and liberation, helping spread the Dharma across geographic and cultural boundaries. In this way, Buddhist cave complexes became powerful agents of religious continuity, cross-cultural exchange, and devotional creativity.

Decline and legacy

The gradual decline of cave monasticism coincided with broader socio-economic and religious shifts in the medieval period. As urban centers grew and Buddhism adapted to more centralized institutions, the need for remote monastic cave retreats diminished. The rise of brick and timber temple construction, supported by expanding cities and royal capitals, offered new architectural paradigms better suited to urbanized Buddhist communities. In some regions, the decline was further accelerated by the rise of rival religious traditions, invasions, and the general erosion of institutional support for Buddhism.

Despite periods of neglect and even deliberate destruction, many cave complexes endured as cultural landmarks and sacred spaces. Their rediscovery and preservation in modern times, often spearheaded by archaeologists, historians, and Buddhist reform movements, have helped reestablish their significance. Sites like Ajanta and Ellora were documented and restored under colonial and postcolonial efforts, while places such as Dunhuang gained renewed scholarly and religious attention for their textual and artistic treasures. International organizations like UNESCO have played a vital role in recognizing these sites as World Heritage monuments, contributing to their long-term conservation.

Even as their monastic function diminished, the legacy of cave architecture has left an enduring imprint on Buddhist temple design. Elements such as the chaitya arch, rock-cut stupas, and meditative cell layouts have been echoed in later brick, wood, and stone temples across Asia. Symbolically, the cave remains a powerful image of spiritual retreat and inner transformation, continuing to influence the architectural vocabulary of Buddhist sanctuaries into the present day.

Conclusion

Buddhist cave temples and monasteries represent a significant chapter in the religious and cultural history of Asia. As architectural forms, they illustrate a distinctive fusion of utility, symbolism, and craftsmanship — serving both the ascetic needs of monastic communities and the devotional aspirations of lay followers. Their physical structure reflects broader developments in Buddhist doctrine, patronage, and ritual practice across centuries.

These sites offer valuable insights into the evolution of Buddhist institutions and artistic traditions, from their origins in modest forest retreats to the development of monumental rock-cut sanctuaries. Their regional diversity underscores the adaptability of Buddhism as it interacted with different cultural and geographical contexts. Moreover, their role in facilitating religious transmission, through visual narratives, inscriptions, and patronage networks, marks them as important vectors in the historical spread of Buddhist teachings.

Although their active use may have diminished, cave sanctuaries continue to function as objects of scholarly interest, pilgrimage, and heritage preservation. Their durability, complexity, and aesthetic value ensure their place not only in the history of Buddhism, but also in the broader study of religion, art, and architecture.

References and further reading

- Dehejia, Vidya, Indian Art, 1997, Phaidon Press, ISBN: 978-0714834962

- Benoy K. Behl, The Ajanta Caves - Ancient Paintings Of Buddhist India, 2023, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9780500296691

- Rajesh Kumar Singh, An introduction to the Ajanta Caves: With examples of six Caves, 2013

- Schlingloff, Dieter, Ajanta: Handbook of the Paintings, 2013, Aryan Books International, ISBN: 978-8173054563

- Huntington, Susan L., The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, 1985, Weatherhill, ISBN: 978-0834801837

- Snellgrove, David L., Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and Their Tibetan Successors, 2019, Orchid Press Publishing Limited, ISBN: 978-9745242128

comments