What is a Buddha?

What kind of being is a Buddha? This question opens the door to some of the most important distinctions in Buddhist thought: between human and divine, teacher and savior, historical individual and timeless archetype. The term “Buddha” appears across almost every branch of the tradition, and yet it is often left undefined or reduced to devotional shorthand. I believe, a more precise and philosophical account is needed.

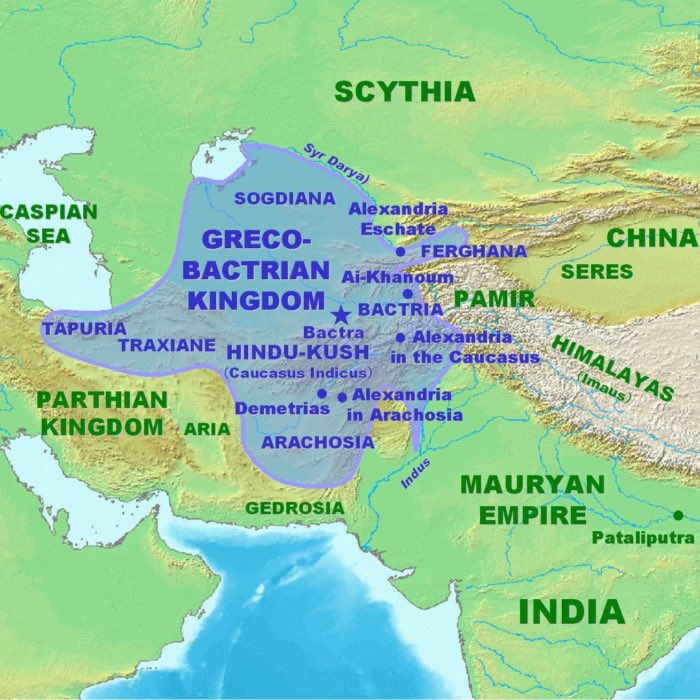

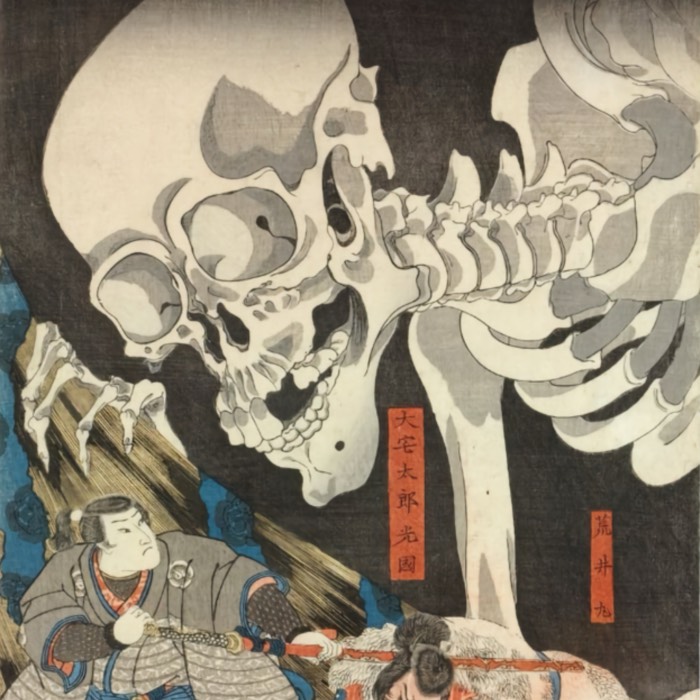

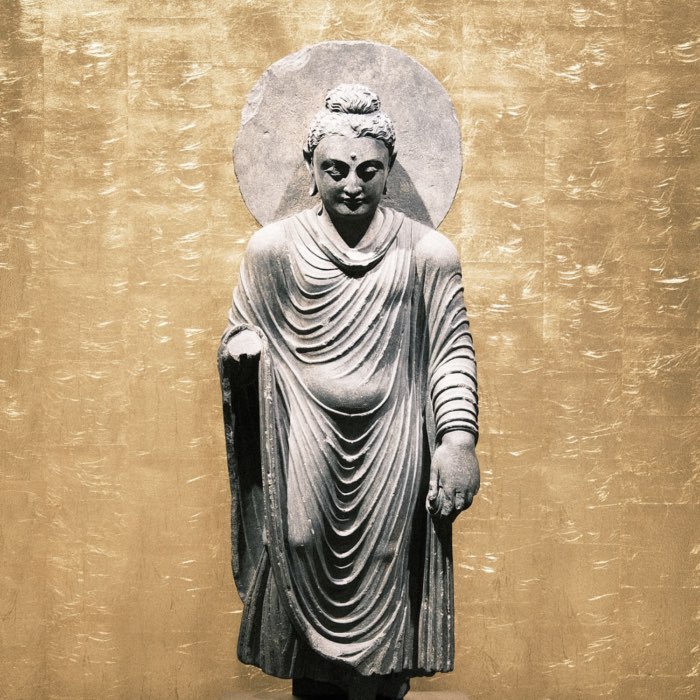

Standing Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara, 1st c., schist, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, 2023.

Standing Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara, 1st c., schist, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, 2023.

Buddhism rests on the idea that the deepest insight into the nature of existence is not the possession of a god or prophet, but can be realized by a human being. The Buddha is the one who has done so fully and without reliance on a prior teacher. Yet this realization, known as awakening, is not a solitary attainment. It opens into a life of wisdom, non-appropriative action, and the capacity to liberate others. To define what a Buddha is, then, is to understand the endpoint of the Buddhist path and the existential structure of its ideal.

Instead of offering a fixed definition, the figure of the Buddha opens onto a wide horizon of meanings. He appears as historical teacher and archetype, as philosopher and savior, as human being and more-than-human presence. To approach this figure requires attention to many layers: the linguistic roots of the term, the doctrinal categories of awakening, the symbolic forms in which he is remembered, and the philosophical reflections that continue to unfold around him. Alongside the Buddha stand related figures such as the Arhat, the Sage, and the Bodhisattva, whose paths illuminate by contrast what is distinctive about “Buddhahood”. From the earliest sources to the sophisticated metaphysics of the Mahāyāna, and from ancient veneration to modern reinterpretation, the meaning of “Buddha” has been contested and renewed. Yet through all these perspectives runs a single thread: the conviction that awakening is both possible and transformative, and that a Buddha embodies the fullest realization of what such transformation can bring.

Introduction

The question What is a Buddha? remains foundational not only to understanding Buddhism as a tradition but also to engaging with its broader philosophical and ethical implications. In both ancient texts and modern discourse, the term “Buddha” is often surrounded by layers of interpretation, symbolism, and cultural projection. Many continue to conflate the Buddha with notions of deity, prophet, or religious founder, i.e., roles that do not align with how early Buddhist texts and later doctrinal developments define Buddhahood.

Buddhahood, in its most concise definition, refers to the state of full and final awakening marked by the eradication of all defilements (kleśas) and the complete realization of reality as it is. A being who has attained Buddhahood has eliminated ignorance, craving, and the illusion of self, and thereby transcended the cycle of birth and death (saṃsāra). But this awakening is not merely a personal liberation, it is coupled with perfect wisdom (prajñā), boundless compassion (karuṇā), and skillful means (upāya) to guide others toward the same freedom. A Buddha acts spontaneously and selflessly, responding to the needs of others without being bound by karmic residue or egoic interest. The state of Buddhahood thus combines the epistemological (seeing things as they are), the ethical (acting with compassion), and the pedagogical (transmitting liberating insight) in a fully integrated and irreversible way.

A Buddha is not a god who intervenes in the world from beyond, nor a prophet delivering a divinely revealed message. Nor is the Buddha merely a moral teacher or philosopher in the conventional sense. Instead, a Buddha is understood as one who has awakened fully to the nature of reality, i.e., to the impermanence, interdependence, and non-self character of all phenomena, and who shares this path of awakening with others. This definition rests on insight, not belief; on experiential realization, not divine inspiration.

To grasp what a Buddha is, one must also distinguish between the historical figure Siddhartha Gautama, a person born into a specific cultural and social context in ancient India, and the doctrinal role of a “Buddha” as formulated across various Buddhist traditions. Gautama is regarded as one historical instance of Buddhahood, but not the only one: past and future Buddhas are acknowledged in the canonical texts, and the state of Buddhahood itself is held to be accessible, in principle, to any being. Thus, understanding “Buddha” involves both biographical specificity and transhistorical significance. It opens a field of reflection on what it means to awaken, and what kind of being emerges from that process.

Etymology and early usage

The term Buddha derives from the Sanskrit root √budh, meaning “to wake”, “to become aware”, or “to know”. Its literal sense is “the awakened one”, referring not to physical awakening from sleep but to the complete and irreversible awakening to the nature of reality. In Pāli, the closely related language of the early Buddhist canon, the term retains the same core meaning. This linguistic root places emphasis on cognitive clarity and experiential understanding, rather than faith or divine inspiration. A Buddha is someone who has come to see and know reality as it truly is, free from distortion, projection, or ignorance.

This core meaning stands in contrast to other titles found in Buddhist discourse. The arahant is also an awakened being, particularly in early Buddhism, but one who reaches awakening by hearing and following the teachings of a Buddha. The term “sage” (e.g., muni) emphasizes meditative silence or insight, but does not imply the same level of spiritual independence. The Bodhisattva, meanwhile, refers to someone on the path to Buddhahood, often driven by compassion and motivated by the aspiration to attain full awakening for the sake of all beings. Thus, while these terms are related, Buddha occupies a distinct position: it refers specifically to one who attains awakening independently and teaches the Dharma from direct insight.

The following table provides an overview of these figures:

| Figure | Definition | Path to awakening | Motivation | Relation to others |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buddha | One who awakens fully and independently, and teaches the Dharma | Self-directed insight through deep meditation and wisdom | Universal compassion; liberates all beings | Guides others by rediscovering and teaching Dharma |

| Arhat | One who attains liberation by following the Buddha’s teachings | Discipleship; realization of the Four Noble Truths | Liberation from saṃsāra | No further rebirth; does not teach independently |

| Sage | A meditative knower or wise recluse (e.g., muni) | Often solitary; emphasizes renunciation and contemplation | Inner peace and clarity | May advise, but not systematically teach Dharma |

| Bodhisattva | One committed to Buddhahood for the benefit of all beings | Path of compassion and wisdom over multiple lifetimes | Altruistic vow (bodhicitta) | Delays own liberation to aid all beings |

Early canonical references, such as those in the Nikāyas of the Pāli Canon or the Āgamas of other early schools, already use the term with this specificity. The Buddha is often described as having rediscovered a timeless truth that had been lost to the world, the Dharma, and as possessing qualities such as perfect wisdom, limitless compassion, and fearlessness. These early texts do not frame the Buddha as a supernatural being, but as an exceptional human whose cognitive and moral capacities have been fully realized. Over time, this doctrinal role became more elaborated in both philosophical and devotional directions, especially in later traditions. Yet the linguistic and conceptual core, i.e, that a Buddha is an awakened knower and teacher of reality, remains remarkably consistent.

The Buddha in early Buddhism

Early Buddhist texts portray the Buddha first and foremost as a human being, Siddhartha Gautama, who lived and taught in northern India around the 5th century BCE. His significance lies not in his birth status or supernatural traits, but in the depth of his awakening: a profound insight into the impermanent, unsatisfactory, and non-self nature of all phenomena. This realization, attained through deep meditative investigation and ethical discipline, marks the turning point in his life from seeker to teacher.

Crucially, early Buddhism does not present the Buddha as a god or divine messenger. He explicitly denied being a god, an avatar, or an eternal soul. Instead, he emphasized that liberation is attainable through one’s own effort, discernment, and practice, and that his own awakening was the result of a long and arduous path of cultivation. His message was thus empowering: it declared that insight into the nature of reality, and the liberation that follows from it, are within reach for all beings willing to practice the path.

The defining qualities of the Buddha, as emphasized in the Nikāyas, include wisdom (paññā), compassion (karuṇā), and equanimity (upekkhā). These are not abstract virtues but embodied dispositions that guided his interactions and teachings. His wisdom enabled him to discern the root causes of suffering and the appropriate means to address them. His compassion motivated his tireless engagement with students of all backgrounds, regardless of caste, gender, or status. And his equanimity allowed him to remain undisturbed by praise and blame, success and failure, always responding from a place of clarity.

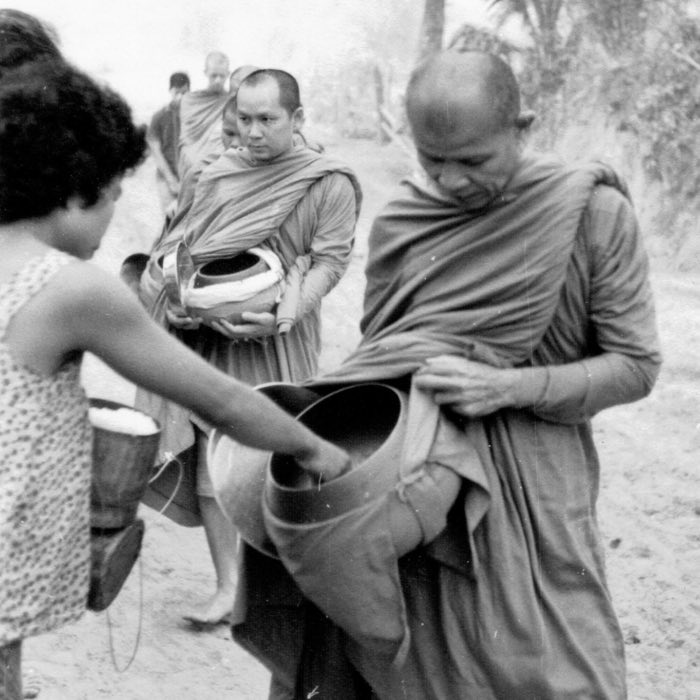

As a teacher, the Buddha described himself as a “finger pointing to the moon”, not the object of worship, but a guide to direct perception. He refused to perform miracles as proof of his authority, instead offering teachings that invited direct experience and personal verification. His role was that of a physician diagnosing illness and prescribing a cure, not a savior who could remove suffering on others’ behalf. This pedagogical model would go on to shape the early sangha and lay the foundation for generations of practitioners who understood awakening not as mystical salvation, but as a reproducible path grounded in reasoned insight and disciplined practice.

Doctrinal categories of awakening

Within classical Buddhist thought, awakening is not a singular, uniform event but a state that may manifest in different forms depending on one’s path and relationship to the Dharma. Buddhist tradition classifies awakened beings into three primary categories: the Samyaksambuddha, the Pratyekabuddha, and the Śrāvakabuddha. Each type is fully liberated, yet they differ in how they arrive at awakening and what role they play in the spiritual development of others.

The Samyaksambuddha (Pāli: Sammāsambuddha) is a fully awakened one who realizes the Dharma through their own insight, without the aid of a teacher, during a time when the true path has been forgotten or lost. This is the most exalted form of Buddhahood in both Theravāda and Mahāyāna traditions, because such a being not only attains enlightenment independently but also possesses the compassionate skill and resolve to teach the path to others. A Samyaksambuddha is thus both a rediscoverer of truth and a universal guide. Siddhartha Gautama is recognized as such a figure.

The Pratyekabuddha (Pāli: Paccekabuddha) also realizes the same truth, the cessation of suffering and the nature of reality, without guidance from another. However, they do not teach the Dharma or establish a community. Their awakening is real and complete, but it occurs in isolation, often during times when no Buddha or formal teaching is present in the world. The Pratyekabuddha is revered for their insight and restraint, but is generally seen as lacking the communicative compassion or the karmic affinity needed to become a world-teacher.

The Śrāvakabuddha is a disciple who attains awakening by hearing and following the teachings of a Samyaksambuddha. In most early texts, this refers to the Arhats who, through disciplined practice and understanding of the Four Noble Truths, attain liberation from saṃsāra. Their liberation is authentic, and they are honored as exemplars of the path. However, their awakening depends on the presence and instruction of a Buddha, and they do not rediscover the Dharma on their own.

The distinctions among these categories carry significant doctrinal and ethical implications. They mark a hierarchy not of spiritual purity or depth of realization since all three are liberated from delusion, but of pedagogical function and historical context. While the Samyaksambuddha assumes the burden of reviving the path for others, the Pratyekabuddha remains apart, and the Śrāvakabuddha completes the journey with the help of guidance.

In both Theravāda and Mahāyāna traditions, the Samyaksambuddha holds a central place. In Mahāyāna, this figure becomes the ideal that all Bodhisattvas aspire to embody, not merely for their own liberation, but for the salvation of all beings. In this sense, the classification is not merely descriptive but aspirational: it defines the framework for how awakening is understood, pursued, and transmitted within the Buddhist world, which we will further explore in the next section.

Buddhahood in Mahāyāna thought

As Mahāyāna Buddhism developed, the concept of Buddhahood underwent profound reinterpretation. While early Buddhist texts emphasized the Buddha’s human life and historical role as a teacher, Mahāyāna thinkers expanded the ontological and cosmological dimensions of what it means to be a Buddha. Rather than seeing the Buddha solely as a historical figure who attained awakening in a specific time and place, Mahāyāna traditions came to view the Buddha as a multidimensional presence that transcends temporal and spatial limits. This view did not negate the historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, but re-situated him within a much broader metaphysical and doctrinal framework.

Central to this redefinition is the doctrine of the Trikāya, the three bodies of the Buddha, which articulates the manifold ways in which a Buddha exists and operates. The Nirmāṇakāya, or “manifestation body”, refers to the physical form a Buddha takes in the world, such as the historical Gautama Buddha. This is the body perceived by ordinary beings, one that teaches, walks, and dies. The Saṃbhogakāya, or “enjoyment body”, is a subtler form accessible to highly advanced Bodhisattvas in meditative visions. It represents the reward of long spiritual cultivation and is often depicted in celestial realms surrounded by retinues of Bodhisattvas. Finally, the Dharmakāya, or “truth body”, is the unconditioned, formless reality that a Buddha embodies. It is the ultimate nature of all things, synonymous with emptiness (śūnyatā) or suchness (tathatā). The Dharmakāya is beyond birth and death and is present wherever truth is realized.

In addition to these metaphysical formulations, Mahāyāna Buddhism introduced the concept of Buddha-nature (tathāgatagarbha), the idea that all sentient beings inherently possess the potential to attain Buddhahood. This notion reframes liberation not as the acquisition of something new, but as the uncovering or actualization of an innate capacity obscured by ignorance and defilements. While the doctrine of Buddha-nature took on various interpretations, from poetic metaphor to metaphysical assertion, it consistently emphasized the universality of the path and the immanence of awakening.

The Mahāyāna reinterpretation of Buddhahood thus blurs the line between historical individual and cosmic principle. The Buddha is both a compassionate teacher who once walked the earth and an ever-present expression of awakened reality. He is simultaneously immanent and transcendent, personal and universal. This expanded vision allowed Buddhists to see the Buddha not only as a past event, but as an ongoing presence manifesting in multiple forms, guiding sentient beings across time and space.

Symbolic and mythic dimensions

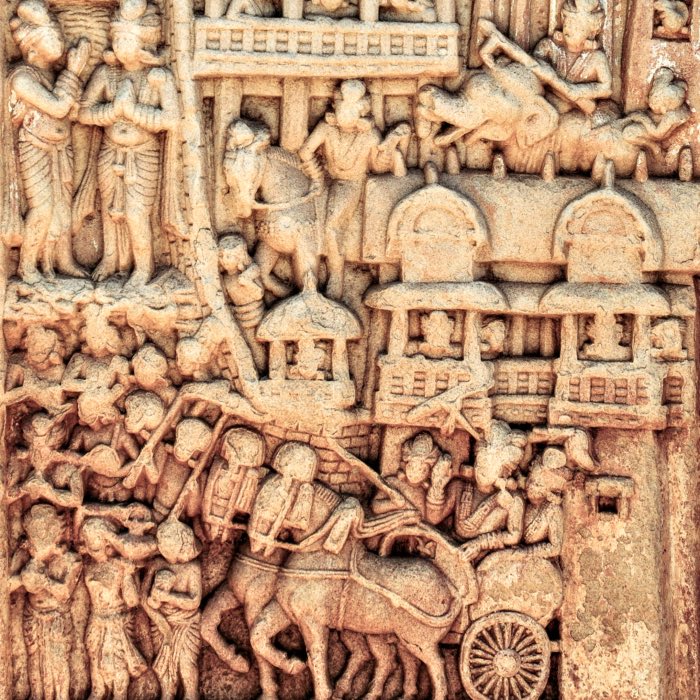

While early Buddhism emphasized the Buddha’s historical and human characteristics, later traditions, particularly Mahāyāna, developed increasingly symbolic and mythic representations that elevated the figure of the Buddha beyond historical time and personal biography. These symbolic layers do not replace the historical Buddha but reinterpret his significance in cosmological, psychological, and artistic terms.

One important development is the emergence of the Buddha as a timeless principle or archetype. Rather than a singular person, the Buddha is understood as the expression of awakened reality itself, the embodiment of wisdom and compassion wherever they arise. This symbolic function allows the Buddha to serve not just as a historical teacher, but as a universal presence accessible through devotion, meditation, and insight. In this way, the Buddha becomes a mirror of the awakened potential inherent in all beings.

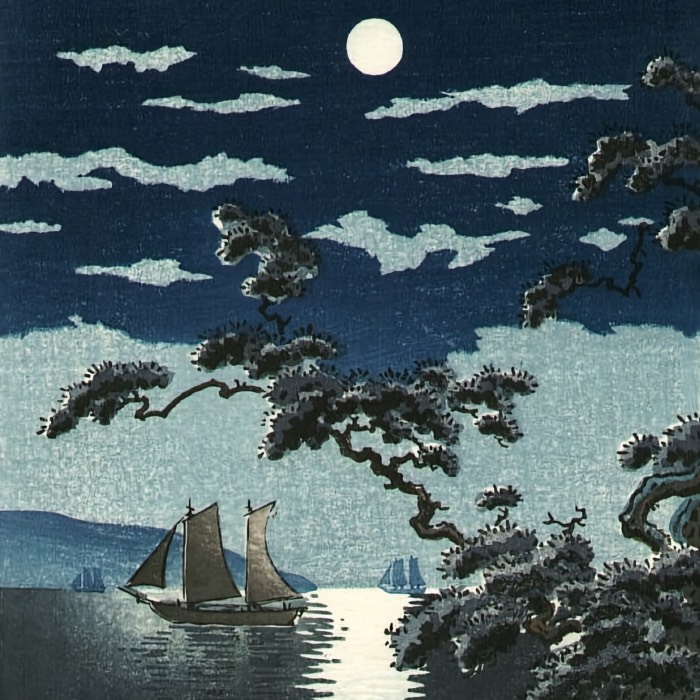

This timeless aspect is further expressed through the recognition of countless past and future Buddhas. Figures such as Dīpaṅkara, who is said to have prophesied the future awakening of Siddhartha Gautama, or Metteyya (Sanskrit: Maitreya), the next Buddha expected to appear in the future, point to a vision of awakening as a cosmic rhythm, not a one-time event. These Buddhas serve as symbols of continuity, hope, and the eternal availability of the path.

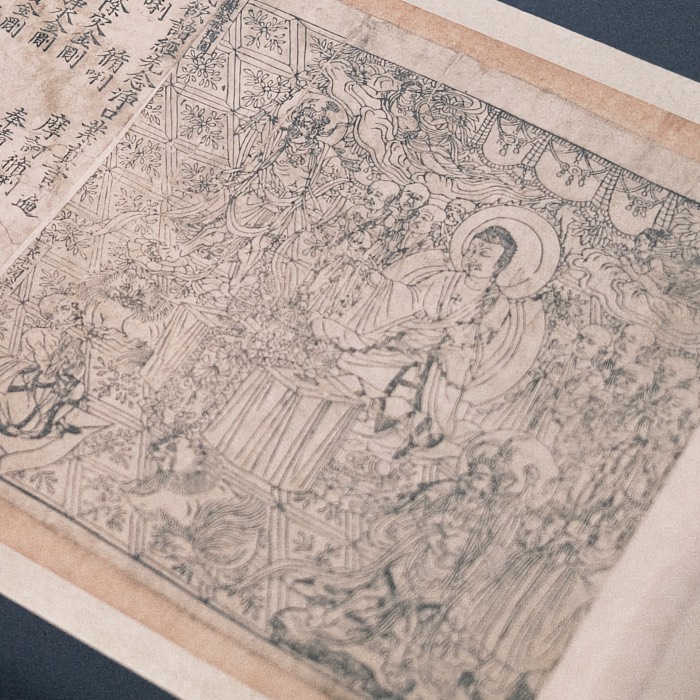

Mahāyāna sūtras elaborate these themes through rich mythic imagery. In the Lotus Sūtra, the Buddha reveals his timeless nature, stating that he attained Buddhahood in the inconceivably distant past and remains present through skillful appearances. The Avataṃsaka Sūtra offers a vision of the Buddha as the center of an infinitely interconnected cosmos, where each moment of reality reflects the whole. A view that dissolves the boundary between history and symbolism.

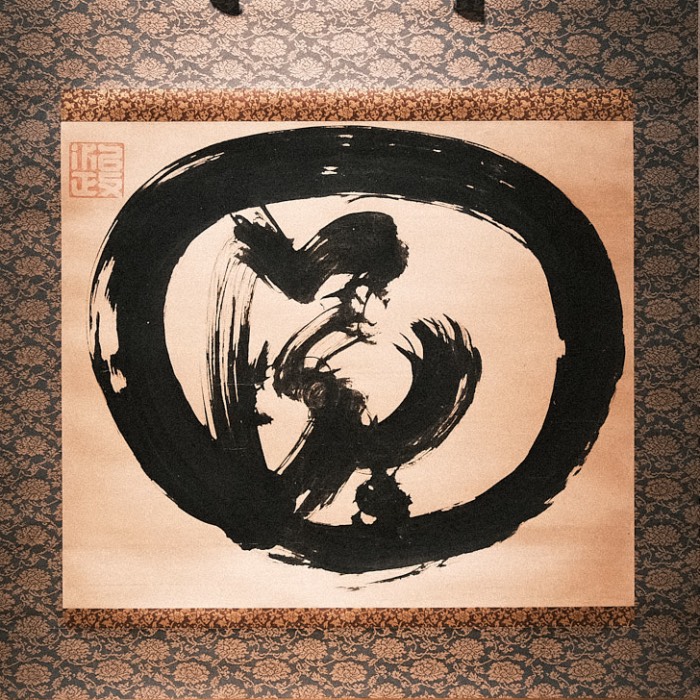

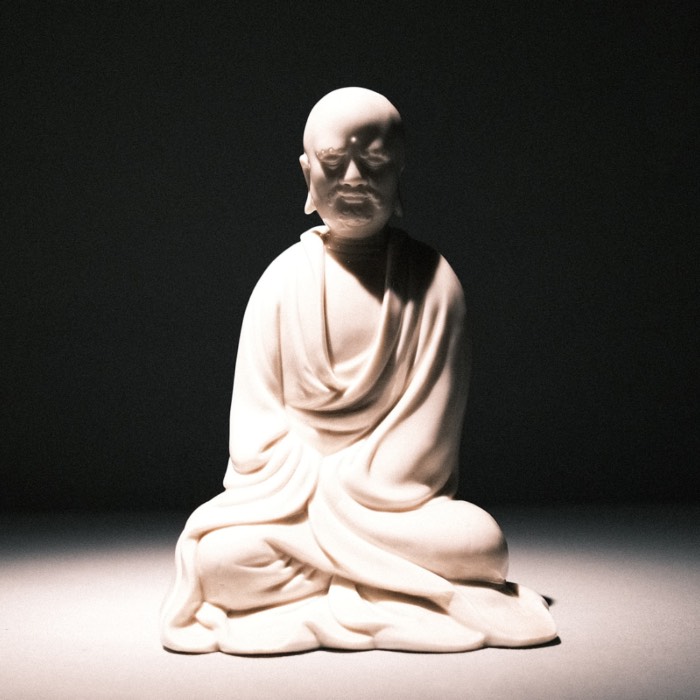

Visual art and iconography further deepen these mythic dimensions. The Buddha is depicted not only in serene meditation, but also surrounded by celestial assemblies, radiating light, seated on lotus thrones, or touching the earth to witness his awakening. These artistic forms do not merely illustrate doctrine but function as symbolic representations of the Buddha’s inner qualities and his cosmic role. They invite the viewer not simply to venerate, but to recognize and cultivate the same awakened potential within themselves.

Together, these symbolic and mythic layers expand the meaning of the Buddha far beyond a biographical figure. They allow the Buddha to function as both a historical exemplar and a timeless embodiment of awakening, a presence that guides, inspires, and reflects the deepest insights of the Buddhist tradition.

Philosophical reflections

To understand the significance of Buddhahood at a philosophical level requires a deeper inquiry into what it means to be awakened, how an awakened being relates to the world, and whether that state constitutes a fixed condition or a dynamic process.

First, awakening in Buddhist thought is not simply the acquisition of knowledge, but a radical transformation of perception. From an epistemological standpoint, a Buddha sees reality “as it is” (yathābhūtañāṇadassana), unfiltered by conceptual distortion, attachment, or egoic projection. This seeing involves the direct realization of three marks of existence: impermanence (anicca), unsatisfactoriness (dukkha), and non-self (anattā). It is not the perception of a hidden metaphysical truth, but the cessation of deluded cognition. In this way, awakening is less about attaining content than about the dissolution of false structuring of experience.

Ontologically, this realization shifts the way a being inhabits the world. A Buddha does not merely see the non-substantiality of self and things; they live from that insight. There is no longer any sense of “I am this” or “I own that”. All actions emerge from non-appropriative awareness. Yet, this does not lead to passivity or detachment in a nihilistic sense. Rather, it gives rise to spontaneous, unselfish responsiveness to suffering. A Buddha acts from the full recognition of interdependence, no longer driven by reactive patterns, but attuned to the needs of others.

This leads to a subtle question about whether Buddhahood is a final state, a perfected condition outside of change, or an ongoing relational presence. While classical sources sometimes speak of the Buddha as having reached the “end of the path”, later traditions, particularly in Mahāyāna, emphasize that a Buddha remains active in the world, continually manifesting for the benefit of beings. Buddhahood, in this view, is not stasis, but freedom: not the termination of activity, but its purification. Because the Buddha is no longer bound by ignorance or karma, their activity is not conditioned by personal interest or suffering, but is creative, responsive, and compassionate.

Thus, philosophically, Buddhahood resists reduction to either essentialism or negation. It is not a metaphysical essence that one attains and possesses, nor merely the absence of delusion. It is an awakened mode of being, clear, unobstructed, and engaged, that embodies the resolution of epistemic confusion, ethical suffering, and existential misidentification in a single unified condition.

Contemporary relevance

In contemporary discourse, the figure of the Buddha continues to serve as a source of ethical inspiration, philosophical depth, and cultural identity across diverse contexts. Yet this continued relevance is marked by a spectrum of reinterpretations, from devotional veneration to secular humanist appropriation, each of which reflects evolving understandings of what it means to be awakened in the modern world.

Many modern Buddhists, particularly in Western or globalized settings, view the Buddha less as a supernatural being and more as an exemplary human: a teacher of psychological insight and existential clarity. This framing emphasizes the reproducibility of awakening: the Buddha is understood as a model for transformation available to all who are willing to undertake the path of ethical discipline, meditative inquiry, and wisdom cultivation. In this context, terms such as “enlightenment” are often reframed in therapeutic or philosophical terms, making Buddhism accessible without the need for metaphysical commitment.

At the same time, there is a growing awareness that reducing the Buddha to a secular self-help figure risks stripping away the radical insights of his teaching. His critique of self, his analysis of dependent origination, and his emphasis on liberation from all forms of clinging offer a vision that challenges rather than affirms dominant cultural assumptions. A genuinely contemporary engagement with the Buddha must thus balance critical demythologization with a willingness to be challenged by his ethical and ontological vision.

Moreover, in many Asian traditions, devotional and ritual expressions remain central. Here, the Buddha is not just a model or idea but a relational presence, one evoked through prayer, visualization, and community. Such forms of devotion are not necessarily in tension with philosophical reflection; rather, they offer different modes of internalizing and actualizing the Buddha’s presence.

In this diversity of interpretations, what remains consistent is the Buddha’s symbolic function: he represents the possibility of transformation grounded in clarity, compassion, and responsibility. Whether approached through faith, philosophy, or practice, the Buddha continues to function as a living archetype, a figure who reminds us that liberation is both an individual task and a universal potential.

Conclusion

A Buddha occupies a distinct category within human and philosophical thought: neither divine nor conventionally ordinary, but rather an existential exemplar, one who has seen reality clearly, and whose life is an expression of that clarity. Defined not by belief but by transformation, a Buddha is a being who has overcome the ignorance and craving that fuel delusion and suffering. Yet this awakening is not an end-point of isolated transcendence. It unfolds in ethical presence and compassionate responsiveness to the world.

The figure of the Buddha integrates insight and action, grounding knowledge not in abstraction but in embodied wisdom. Buddhahood represents the culmination of a path, but also the opening of a new orientation: one no longer structured by egoic interest or reactive patterning. Such a being acts without appropriation, teaches without authority-seeking, and responds without attachment. The state of awakening is thus not passive liberation but active lucidity.

Across Buddhist traditions, the Buddha has been interpreted as historical teacher, cosmic principle, timeless archetype, and mirror of our own potential. These interpretations vary in metaphysical tone, but they converge on a core insight: that the capacity to wake up — to see clearly, act wisely, and live compassionately — is not reserved for the divine, but is rooted in the structure of human possibility itself.

In that sense, Buddhahood extends beyond sectarian boundaries. It functions as a model of integrated clarity and responsibility, relevant not only within Buddhist belief but as a symbol of what a life liberated from self-delusion might look like. Whether approached philosophically, ritually, or pragmatically, the Buddha remains a compelling figure: not to be worshiped, but to be understood, and perhaps, in part, emulated.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments