Avalokiteśvāra: The embodiment of compassion

Avalokiteśvāra, the Bodhisattva of compassion, is one of the most beloved and enduring figures in Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism. Revered across cultures and traditions, he embodies the ideal of boundless compassion and the commitment to alleviate the suffering of all beings. This post explores Avalokiteśvāra’s origins, iconography, philosophical significance, and cultural adaptations, highlighting his role as both a devotional focus and an ethical model for practitioners on the path to awakening.

Bronze statue of Avalokiteśvara from Sri Lanka, ca. 750 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Introduction

Avalokiteśvāra is one of the most revered and enduring figures in Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism, embodying the ideal of boundless compassion that lies at the heart of the Bodhisattva path. As a cosmic Bodhisattva, he represents the active dimension of wisdom responding to the suffering of sentient beings, tirelessly working to alleviate distress and guide others toward liberation. His name, which can be translated as “Lord Who Looks Down” or “Observer of the Cries of the World”, signifies this commitment to attentiveness and responsiveness.

Across Buddhist cultures, Avalokiteśvāra has inspired widespread devotion and has taken on diverse iconographic and ritual forms. In India, he emerged in Mahāyāna sūtras as a celestial being of great power and compassion. In Tibet, he is venerated as Chenrezig and is intimately associated with the Dalai Lama lineage, seen as its human incarnation. In China, Avalokiteśvāra evolved into the widely worshiped and often female Guanyin, while in Japan, the Bodhisattva is honored as Kannon, a figure of mercy and intercession. Similar expressions can be found across Southeast Asia, reflecting the flexibility and cultural integration of his compassionate presence.

More than a divine savior, Avalokiteśvāra serves as a moral and contemplative model. He exemplifies the fusion of wisdom and compassion that characterizes the Mahāyāna vision of enlightenment — not as personal escape from saṃsāra, but as the commitment to remain engaged within it for the benefit of others. His symbolism and practice thus speak equally to doctrinal depth and devotional immediacy, offering practitioners a deeply human path of empathy, responsiveness, and ethical resolve.

Origins and scriptural foundations

Avalokiteśvāra first appears prominently in Mahāyāna sūtras, particularly the Saddharmapuṇḍarīka Sūtra (Lotus Sūtra), where he is depicted as a compassionate being who responds to the cries of suffering sentient beings in any form necessary. The 25th chapter of the Lotus Sūtra, often circulated as a standalone text in East Asia, presents Avalokiteśvāra as a near-universal savior who can manifest in countless ways — male or female, monk or layperson, human or celestial — to aid those in distress. Another early source, the Karuṇāpuṇḍarīka Sūtra, elaborates on his boundless mercy and his vow to alleviate the suffering of all beings through skillful means.

Initially described as a celestial Bodhisattva who had made a profound vow to remain within saṃsāra until all beings are liberated, Avalokiteśvāra gradually evolved into one of the most beloved and accessible figures of devotion. This evolution reflects not only doctrinal developments within Mahāyāna thought but also a widespread popular need for a compassionate intermediary between ultimate truth and everyday suffering. Over time, Avalokiteśvāra was no longer simply a rarefied philosophical symbol of compassion but a central devotional figure worshiped across Buddhist cultures.

In the broader Mahāyāna pantheon, Avalokiteśvāra is often described as the spiritual offspring or emanation of Amitābha Buddha, particularly in texts associated with Pure Land traditions and certain tantric cycles. This affiliation reflects a deeper symbolic alignment: Amitābha embodies boundless light and wisdom, while Avalokiteśvāra embodies the active manifestation of that wisdom as compassionate response. Their relationship affirms the Mahāyāna vision of Buddhahood as inseparable from the vow to serve others, and it situates Avalokiteśvāra as the ideal Bodhisattva whose presence bridges the transcendent and the immanent.

Iconography and symbolism

Avalokiteśvāra’s iconography is as rich and varied as his cultural manifestations, reflecting his protean ability to assume countless forms in service of sentient beings. He appears in a wide array of depictions, ranging from the serene two-armed figure holding a lotus flower to the complex and visually striking thousand-armed, eleven-headed manifestation.

The most basic form portrays Avalokiteśvāra as a seated or standing figure with two arms, often holding a lotus (padma), symbolizing purity and spiritual awakening. This lotus is typically depicted as either blossoming or budding, representing the unfolding of compassion in a defiled world. In more elaborate depictions, Avalokiteśvāra is shown with four arms: two joined in the gesture of devotion (anjali mudrā), and two holding sacred implements such as a crystal rosary and a lotus. These symbolize his continuous activity in the world and the unity of method and wisdom.

Perhaps the most dramatic visual form is the eleven-headed, thousand-armed Avalokiteśvāra. According to legend, upon seeing the suffering of beings across the cosmos, Avalokiteśvāra’s head shattered into ten pieces from the sheer intensity of compassion. Amitābha, his spiritual father, reassembled the fragments into eleven heads, including one wrathful face to subdue negative forces. To further enhance his ability to aid beings, he was granted a thousand arms, each with an eye in the palm, symbolizing the union of wisdom (eye) and compassionate activity (hand). This iconographic form conveys his boundless responsiveness to suffering in all directions.

Across cultures, Avalokiteśvāra assumes locally adapted forms. In India and Southeast Asia, he appears as Lokeśvara, often in regal posture, adorned with princely ornaments. In Tibet, he is Chenrezig, commonly visualized as four-armed and white in color, embodying pure compassion. In Chinese Buddhism, Avalokiteśvāra evolved into Guanyin, frequently portrayed as a female figure clothed in white robes, sometimes standing on a lotus or near a willow tree. This feminization reflects a cultural shift toward maternal qualities of mercy and tenderness. In Japan, the same figure appears as Kannon, often with a more understated, contemplative demeanor, yet equally accessible and compassionate.

The recurring motifs in Avalokiteśvāra’s imagery — the downward gaze, the gentle smile, the posture of receptivity — all reinforce his role as a compassionate witness and responder. Each gesture, implement, and form is laden with symbolic meaning, reinforcing the idea that his compassion is not abstract or aloof but intimately involved with the lived experience of suffering beings.

Philosophical and soteriological dimensions

Avalokiteśvara holds a central position in Mahāyāna philosophical thought as the embodiment of bodhicitta, the awakened mind imbued with the intention to liberate all beings. More than a symbolic figure, he represents the dynamic expression of compassion informed by wisdom, a foundational ideal in the Bodhisattva path. His compassionate responsiveness is not sentimental or impulsive but is grounded in profound insight into the nature of reality, making him a primary model of upāya (skillful means): the ability to adapt one’s actions to the conditions and capacities of others in order to lead them toward liberation.

This integration of wisdom and compassion is key to Avalokiteśvara’s philosophical significance. Compassion (karuṇā) alone, without the insight of emptiness, risks becoming entangled in emotional reactivity or self-reference. Conversely, wisdom (prajñā) without compassion can devolve into cold abstraction. Avalokiteśvara transcends this dichotomy by acting from a state of non-dual awareness, where compassionate engagement arises spontaneously from the recognition that there are no fixed selves to save or be saved. His activity is neither passive nor coercive but perfectly attuned to the interdependent fabric of experience.

In this light, Avalokiteśvara’s responsiveness is closely linked to the Mahāyāna understanding of śūnyatā (emptiness). Since all phenomena lack inherent existence and arise in dependence upon causes and conditions, the suffering of beings is both real in its effects and empty in its essence. Avalokiteśvara’s compassion recognizes this paradox and responds with both urgency and equanimity. He is not saving beings in the conventional sense, but liberating them from the misperception that their suffering and selfhood are fixed or immutable. His manifold manifestations thus serve as metaphors for how enlightened awareness meets the world: with skill, flexibility, and profound empathy.

Through this lens, Avalokiteśvara is not merely a devotional focus but a philosophical exemplar. He illustrates the practical enactment of Buddhist metaphysics in ethical and existential terms. His soteriological function lies in modeling how the insight into emptiness does not lead to disengagement but to a deepened capacity to respond to suffering without attachment or aversion. In this way, Avalokiteśvara makes visible the core Mahāyāna claim that wisdom and compassion are not separate virtues, but two facets of the same awakened mind.

Devotional cult and practices

Avalokiteśvara occupies a central place in the devotional landscape of Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism, serving as both an accessible object of worship and a powerful aid in spiritual practice. Across Buddhist cultures, his name is invoked, his image revered, and his mantra repeated as acts of both veneration and personal transformation.

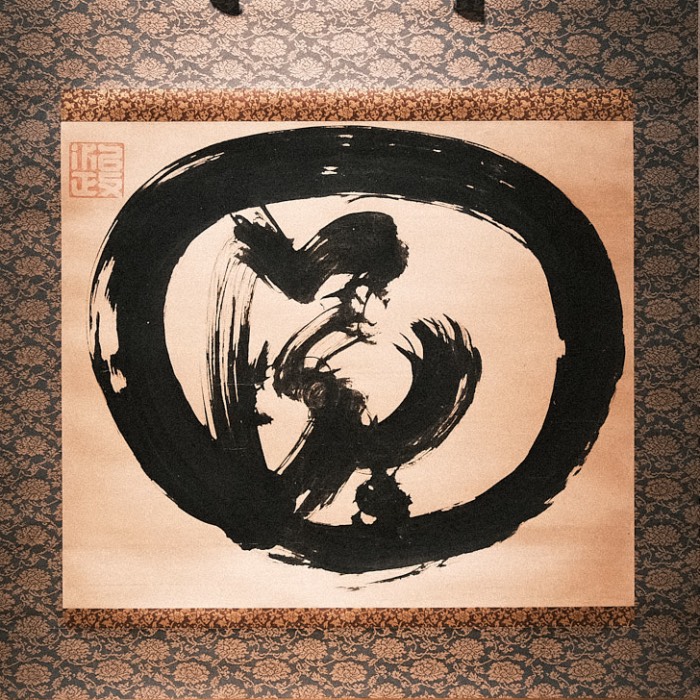

One of the most well-known expressions of devotion to Avalokiteśvara is the recitation of his six-syllable mantra: Om Maṇi Padme Hūm. This mantra, especially prevalent in Tibetan Buddhism, is considered a complete encapsulation of the Bodhisattva path. Each syllable is said to purify one of the six realms of saṃsāric existence, transforming negative emotions into their corresponding enlightened wisdoms. While interpretations vary, the phrase is broadly understood as an invocation of the jewel (maṇi) of compassion in the lotus (padme) of wisdom. The mantra is recited during meditation, inscribed on prayer wheels, carved into stones, and worn as amulets, functioning both as a sonic expression of devotion and a tool for mental cultivation.

In Vajrayāna practice, Avalokiteśvara features prominently in visualizations and sādhanās (structured meditative rituals). Practitioners are guided to visualize Avalokiteśvara either before them or as their own divine form, surrounded by radiating light, adorned with symbolic ornaments, and emitting his mantra. These practices are designed to purify perception, cultivate bodhicitta, and establish a direct affective and cognitive connection with the Bodhisattva. Through repeated engagement, the practitioner internalizes Avalokiteśvara’s qualities, gradually embodying his compassionate responsiveness.

Devotion to Avalokiteśvara also plays a significant role in Pure Land Buddhism, particularly in East Asia. Although Amitābha is the central figure in Pure Land traditions, Avalokiteśvara is often described in sūtras as his primary attendant, assisting practitioners at the moment of death and guiding them into the Pure Land. In this context, Avalokiteśvara functions as a compassionate intermediary, responding to sincere calls for help and easing the transition between life and rebirth. For many lay practitioners, prayers to Avalokiteśvara offer comfort, moral guidance, and spiritual assurance.

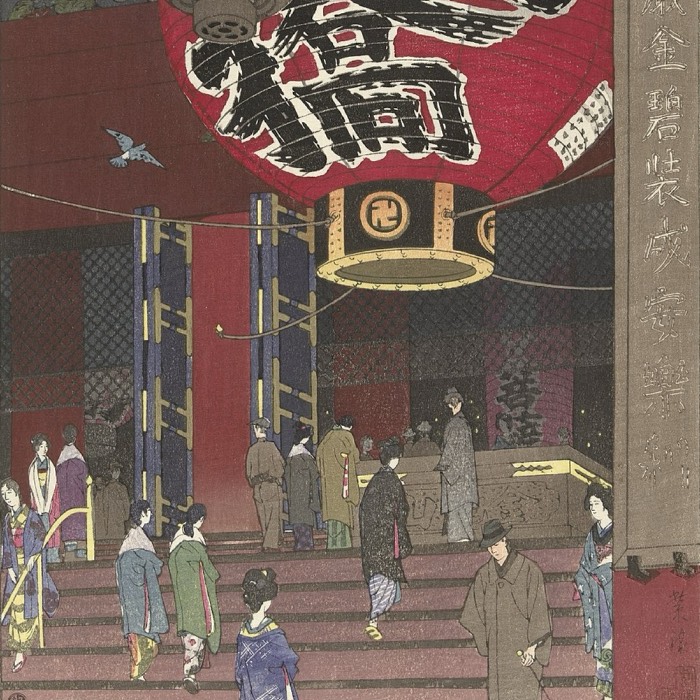

In addition to monastic and tantric contexts, Avalokiteśvara devotion is widely practiced among lay Buddhists through temple rituals, chanting assemblies, and offerings of incense and flowers. His presence is invoked in times of illness, grief, fear, and joy. This accessibility makes Avalokiteśvara not only a philosophical ideal but a living presence in the devotional lives of millions, reinforcing the Mahāyāna emphasis on compassion as the most immediate and universal expression of the awakened mind.

Cultural adaptations and local expressions

Avalokiteśvāra’s cultural adaptability is one of the most striking features of his long historical presence. As Buddhism spread across Asia, local religious, artistic, and social traditions shaped the appearance and worship of this Bodhisattva in diverse ways, often leading to new interpretations that reflected regional values and devotional styles.

In Chinese Buddhism, Avalokiteśvāra underwent a notable transformation into the female figure of Guanyin. While early representations in China maintained the Bodhisattva’s traditionally masculine or androgynous form, by the Tang dynasty Guanyin had increasingly taken on a feminine appearance. This feminization was not merely aesthetic but reflected deep cultural associations between compassion, maternal care, and mercy. Guanyin became a beloved figure of popular piety, worshipped not only in temples but also in household shrines. She was invoked for protection, fertility, healing, and safe travel, and her accessible, human-like demeanor allowed her to bridge elite monastic practice and folk devotion. Her iconography became softer, often showing her in flowing robes, holding a willow branch or vase, or accompanied by a child, reinforcing her maternal qualities.

In Tibet, Avalokiteśvāra is venerated as Chenrezig and holds a central place in Tibetan religious identity. The Dalai Lamas are believed to be emanations of Chenrezig, a connection that not only underscores the Bodhisattva’s spiritual stature but also grounds Tibetan political authority in a soteriological framework. The four-armed form of Chenrezig is particularly prominent in Tibetan ritual and visualization, and his mantra Om Maṇi Padme Hūm is inscribed on countless prayer wheels, flags, and stones across the Himalayan landscape. His presence permeates Tibetan cultural and religious life, embodying the collective aspiration for compassion and spiritual resilience.

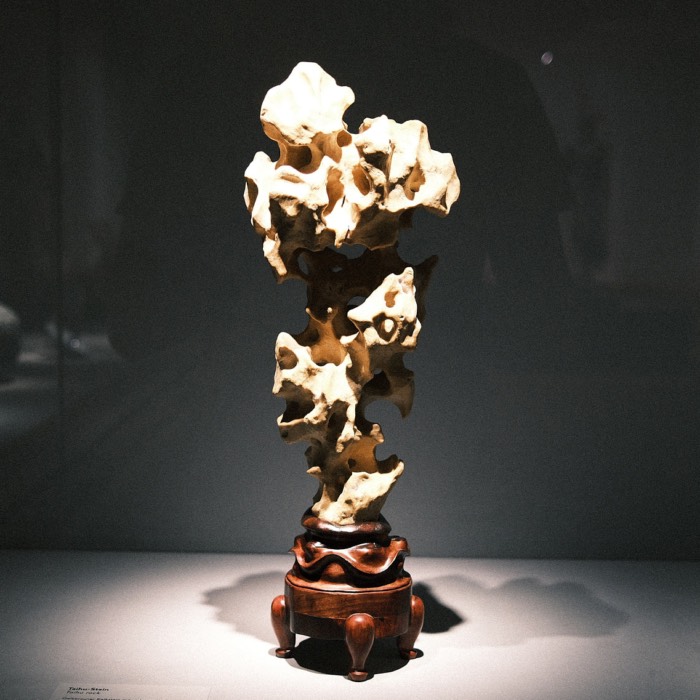

In Southeast Asia, Avalokiteśvāra appears in early Mahāyāna art and inscriptions, particularly in regions influenced by Indianized kingdoms such as Srivijaya, Champa, and Khmer Cambodia. While Theravāda traditions eventually became dominant in these regions, historical evidence shows that Avalokiteśvāra was once widely revered. Artistic depictions from this period often show Avalokiteśvāra in elegant, regal poses, adorned with jewels and seated in niches within temple architecture. These forms emphasize his majesty and benevolence, suggesting a vision of kingship aligned with compassionate rule.

These regional expressions demonstrate Avalokiteśvāra’s remarkable versatility and his capacity to resonate with a wide array of cultural and devotional contexts. Whether as the maternal Guanyin, the sovereign Chenrezig, or the noble Lokeśvara, he remains a dynamic figure whose core symbolism adapts without losing its essence: the vow to hear the cries of the world and respond with unwavering compassion.

Avalokiteśvāra and the ethical ideal of the Bodhisattva

Avalokiteśvāra is not only an icon of devotion but also a profound ethical model within Mahāyāna Buddhism. He exemplifies the Bodhisattva ideal in its most committed and engaged form: the vow to forgo final liberation until all sentient beings are freed from suffering. This commitment underlines the Mahāyāna emphasis on solidarity over self-liberation, and makes Avalokiteśvāra a paradigm of non-abandonment and ethical interdependence.

This ethical stance is deeply embedded in the concept of bodhicitta, the aspiration to awaken not for personal salvation but for the benefit of all beings. Avalokiteśvāra’s defining quality is his refusal to withdraw from saṃsāra, even after attaining a level of realization that could permit it. Instead, he listens to the cries of the world and responds with unceasing compassion. This model of engaged presence challenges any conception of spiritual detachment that neglects the suffering of others and affirms that wisdom must be coupled with ethical responsibility.

In Mahāyāna ethics, Avalokiteśvāra’s example inspires a relational view of morality, one rooted in attentiveness, responsiveness, and the refusal to ignore the pain of others. He embodies what might be called intersubjective responsibility, i.e., the recognition that one’s own liberation is inseparable from the well-being of others. This vision promotes a form of ethical behavior that is not rooted in rigid rules but in empathy, situational awareness, and a vow to alleviate suffering wherever it appears.

In contemporary contexts, Avalokiteśvāra continues to serve as a source of ethical inspiration for Buddhist humanitarianism and social engagement. His iconography and narrative have been invoked by socially engaged Buddhists who see in him a model for active compassion in the face of structural violence, environmental degradation, and social injustice. The idea that one should listen carefully and respond skillfully to suffering, even when it is overwhelming, remains a powerful guide for those integrating Buddhist ethics into the challenges of modern life.

Thus, Avalokiteśvāra offers not just an object of veneration but a practical ethical framework. His example affirms that true compassion does not retreat from the world but engages it fully, and that the path to awakening lies not in escape but in courageous solidarity with all beings.

Conclusion

Avalokiteśvāra stands as one of the most powerful embodiments of Mahāyāna values, uniting the philosophical sophistication of Buddhist doctrine with the emotional immediacy of devotional practice. Across cultures and historical periods, he has remained a symbol of engaged compassion, not as an abstract principle but as an actionable path of ethical responsiveness and meditative clarity.

Through his multifaceted iconography, Avalokiteśvāra makes visible the Mahāyāna understanding that wisdom and compassion are not separate qualities but mutually reinforcing dimensions of awakening. His many forms reflect the core Buddhist insight into non-self and interdependence, demonstrating how responsiveness to suffering must be both skillful and grounded in the realization of emptiness. His ethical stance, grounded in the Bodhisattva vow, challenges any inclination toward individual escape from saṃsāra and affirms a commitment to universal liberation.

Soteriologically, Avalokiteśvāra represents the possibility that enlightenment does not entail disengagement but manifests most fully in the capacity to meet the world without aversion or appropriation. Whether visualized in tantric ritual, invoked in popular devotion, or modeled in ethical life, his presence affirms that the path to Buddhahood is found not beyond the world but within it — through the sustained, fearless embrace of its suffering and complexity.

In this sense, Avalokiteśvāra is not merely a figure of comfort or aspiration. He functions as a mirror of the practitioner’s own potential for clarity, courage, and care. His relevance lies in his ability to bring together doctrinal insight and practical compassion, offering a vision of awakening that is both transcendent in scope and intimately human in application.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments