Archaeology of Buddhist sites: Tracing the historicity of early Buddhism

Buddhism is not only a system of philosophical insight and religious practice, but also a historical tradition grounded in the biography of its founder. While Siddhartha Gautama has long been the subject of canonical texts and devotional legends, archaeology offers a complementary perspective: one grounded in material remains, inscriptions, and the spatial development of sacred sites. In this post, we explore the scientific investigation of the most important places traditionally associated with Siddhartha’s life. We also examine what archaeology can contribute to our understanding of Siddhartha’s historicity and the earliest phases of Buddhist institutional development, while aiming to provide a nuanced perspective that balances faith and historical inquiry.

Remains of some structures (houses or the Royal Palace?) in Tilaurakot, the site of the city of Kapilavastu in Nepal (close to Lumbini). It is said that Siddhartha Gautama grew up in this city. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Introduction

The life of Siddhartha Gautama, known as the historical Buddha, has inspired reverence, legend, and philosophical inquiry for more than two millennia. Yet from a historical and scientific standpoint, one of the most pressing questions remains: What can archaeology tell us about the man behind the tradition? The physical remains of early Buddhist sites provide a rare but crucial window into this question.

Archaeological evidence plays a central role in contextualizing the development of early Buddhism. Excavations at sites traditionally linked to events in Siddhartha’s life — his birth, awakening, teaching, and death — offer material support for the plausibility of the canonical narratives. More importantly, these sites shed light on the formation of the early monastic community (sangha), the sociopolitical conditions of early Buddhist practice, and the expansion of Buddhist institutions.

At the same time, Buddhist archaeology presents unique challenges. Many sites underwent centuries of renovation, reinterpretation, and layering by later dynasties and devotional movements. Structures considered sacred were often rebuilt over older ones, sometimes obliterating the original context. The use of symbolism, anachronistic claims, and pious inscriptions complicates the task of distinguishing historical memory from devotional myth.

Despite these challenges, archaeological science, combined with epigraphy, stratigraphy, and carbon dating, allows for a cautious but increasingly nuanced reconstruction of Buddhism’s earliest phase. This article explores major archaeological sites linked to Siddhartha’s life and evaluates what they reveal about his historicity and the emergence of the Buddhist tradition.

Methodology and historical framework

Understanding the archaeological basis of early Buddhist sites requires a multidisciplinary approach that draws upon stratigraphy, material culture analysis, epigraphy, and radiocarbon dating. Each of these methods contributes uniquely to establishing a historical framework that can support or challenge traditional narratives about the life of Siddhartha Gautama and the early Buddhist community.

Stratigraphy, the analysis of soil and cultural layers, allows archaeologists to reconstruct chronological sequences of occupation and construction at sacred sites. For example, at Bodhgayā and Lumbinī, excavations have uncovered multiple occupational phases, including timber structures beneath later brick shrines, suggesting pre-Mauryan cultic activity that may be contemporaneous with Siddhartha’s lifetime.

Epigraphy plays a particularly decisive role. Inscriptions found on pillars, railings, and reliquaries provide not only dating anchors but also historical insights. The most critical examples include the Ashokan pillars, which directly reference the Buddha and his birthplace, and reliquary inscriptions at Piprahwa mentioning the “Sākya brethren” (refers to members of the Śākya clan, the noble family to which Siddhartha Gautama belonged). These inscriptions offer the earliest textual evidence for a historical Buddha figure and for the veneration of his relics.

Radiocarbon dating of organic materials (such as wooden postholes or burnt offerings) further refines chronological estimates, especially when applied to early structural remains predating monumental construction. Coupled with typological analysis of ceramics and architectural elements, radiocarbon data can establish whether a site shows continuity from the purported time of Siddhartha to the era of institutional Buddhism.

An essential actor in this historical reconstruction is Emperor Ashoka (3rd century BCE), whose patronage of Buddhist monuments across the Indian subcontinent dramatically shaped the physical and commemorative landscape of early Buddhism. Ashoka not only erected pillars and stupas at major sites associated with Siddhartha’s life, but also left inscriptions that identify those sites explicitly. Without Ashoka’s interventions, many of these sacred locations may never have survived — or been known — as loci of ancient Buddhist devotion.

However, scholars must exercise caution when interpreting these findings. The correspondence between traditional accounts and archaeological data is not always precise or uncontested. Sacred sites often underwent centuries of reinterpretation and rebuilding, especially during periods of Buddhist resurgence or royal sponsorship. Later identifications of a place as a “Buddha site” may reflect devotional memory more than historical accuracy.

Therefore, while archaeology can corroborate aspects of early Buddhist tradition, it must be approached critically and comparatively. The goal is not to confirm legend, but to illuminate the historical processes that gave rise to it. In this post, we therefore adopt a balanced perspective that respects both the devotional significance of these sites and the rigorous demands of historical inquiry.

Lumbinī: Siddhartha’s birthplace

Lumbinī, located in present-day Rupandehi District of Nepal, is universally recognized in Buddhist tradition as the birthplace of Siddhartha Gautama. The most compelling archaeological support for this claim came in 1896, when a team led by Khadga Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana and Alois Anton Führer uncovered a sandstone pillar bearing a Brahmi inscription. This Ashokan pillar, erected during the 3rd century BCE, states that Emperor Ashoka visited Lumbinī and identified it as the Buddha’s birth site. The inscription notes that Ashoka exempted the village from tax and endowed it with a reduced land revenue obligation, an action consistent with his other known acts of religious patronage.

Ancient ruins at Lumbini, Nepal. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

While the Ashokan pillar alone is strong evidence for the traditional identification of Lumbinī, further archaeological discoveries have deepened the site’s significance. Excavations at the Maya Devi Temple, particularly between 2010 and 2013, revealed structural remains below the brick platform of the later temple. Among the most significant findings was a wooden posthole structure, interpreted as part of a pre-Mauryan timber shrine dating to the 6th century BCE. This places it roughly within the plausible time frame of Siddhartha’s life, according to both traditional and some modern scholarly chronologies.

Ashoka Pillar of Lumbini, Nepal. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

This earlier shrine, surrounded by evidence of ritual activity such as burnt soil and votive offerings, suggests that Lumbinī had already become a place of pilgrimage before Ashoka’s time. The architectural continuity from a modest wooden structure to a monumental brick temple reflects the sanctification and monumentalization of key sites over centuries. Importantly, the pre-Mauryan remains support the idea that Lumbinī was not simply assigned sacred status retrospectively but had local significance that predated imperial endorsement.

Marker stone, supposedly marking the exact spot of Siddhartha Gautama’s birth, Lumbini, Nepal. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Taken together, the epigraphic, stratigraphic, and structural evidence makes Lumbinī one of the most archaeologically credible sites linked to Siddhartha Gautama. It stands as a key case where traditional Buddhist narratives and material findings converge, offering a rare and tangible reference point in the study of early Buddhism.

Kapilavastu: Siddhartha’s early years

Kapilavastu is traditionally identified as the capital of the Śākya clan and the place where Siddhartha Gautama spent his childhood and early adult life. However, the precise location of ancient Kapilavastu remains a matter of scholarly debate. Two main archaeological sites compete for this identification: Tilaurakot, in present-day Nepal, and Piprahwa, located across the border in India.

Remains of the East Gate of the ancient city of Kapilavastu, Tilaurakot, Nepal. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Tilaurakot has gained increasing favor among archaeologists due to its extensive urban layout, fortified gates, and long-term occupation layers. Excavations there have revealed thick walls, moats, and urban planning consistent with an administrative or noble settlement from the 9th to the 6th centuries BCE. Numerous small artifacts such as coins, seals, and pottery sherds indicate sustained settlement and local governance. The site’s strategic location and alignment with ancient trade routes further reinforce its plausibility as a Śākya stronghold.

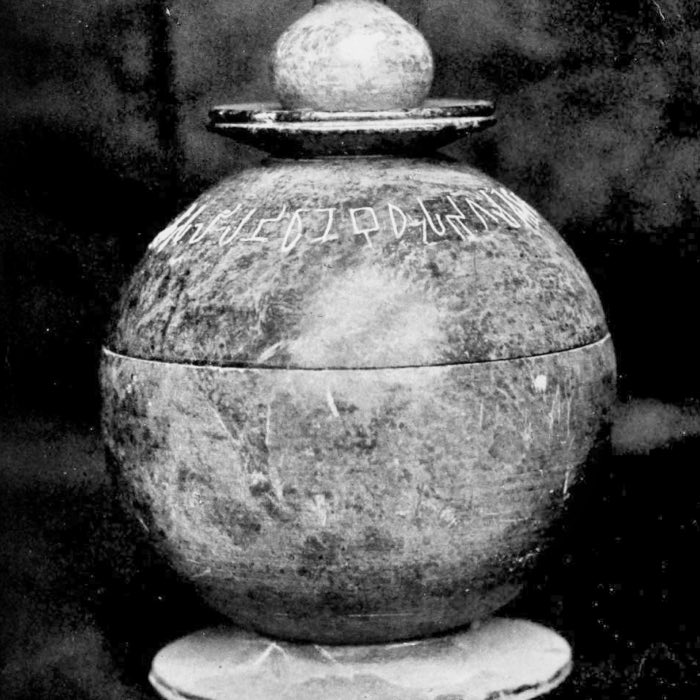

Piprahwa, on the other hand, is most famous for the discovery of a reliquary stūpa in 1898 by William Claxton Peppé. Inside the stūpa was a soapstone casket bearing a Brahmi inscription that some scholars interpret as referring to the “brethren of the Śākya clan” and the relics of the Buddha himself. If authentic and correctly interpreted, this would be an extraordinary find. However, controversy persists around the exact reading and dating of the inscription. Some have raised doubts about its paleography and the context of the discovery. Nonetheless, the Piprahwa site does contain later-period stūpas and monastic ruins, indicating it was a place of early Buddhist reverence.

The broader region, including both Piprahwa and Tilaurakot, likely formed part of the Śākya domain, and it is possible that both sites reflect different aspects of early Śākya and Buddhist history. From an archaeological standpoint, Tilaurakot presents the strongest urban and architectural evidence for a political center corresponding to the narrative of Siddhartha’s princely background. Piprahwa, while less architecturally informative, offers potential insights into relic worship and early Buddhist devotional practices.

The dual possibilities serve as a reminder of both the richness and complexity of early Buddhist geography. Archaeology here does not resolve the debate with finality, but it does reveal a robust material culture that supports the existence of a politically and culturally significant Śākya center in the region during the likely time of Siddhartha Gautama.

Bodhgayā: Enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree

Bodhgayā, located in the modern Indian state of Bihar, is universally revered as the site where Siddhartha Gautama attained enlightenment beneath the Bodhi Tree, becoming the Buddha. Of all locations associated with his life, Bodhgayā has remained a continuous center of pilgrimage and worship for over two millennia. Its archaeological and architectural layers reflect this deep and uninterrupted veneration.

The Bodhi Tree at Bodhgayā, India, is a sacred fig tree (Ficus religiosa) located in the Mahābodhi Temple complex. It is revered as the tree under which Gautama Buddha is said to have obtained Enlightenment. The current tree is believed to be a direct descendant of the original Bodhi Tree. The temple complex surrounding it has been a pilgrimage site for centuries, and it is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Bodhi Tree symbolizes wisdom and enlightenment in Buddhism, and it continues to attract pilgrims and visitors from around the world. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Modern excavations have provided compelling stratigraphic evidence for the site’s antiquity. Beneath the current Mahābodhi Temple complex, archaeologists have uncovered earlier brick platforms and traces of structural foundations, including circular shrine bases and postholes. These strata suggest the existence of cultic activity at the site well before the major constructions of the Mauryan period. Some timber elements suggest possible ritual use of the site as early as the 6th century BCE, aligning with traditional timelines for Siddhartha’s enlightenment.

The most significant historical developments at Bodhgayā came during the reign of Emperor Ashoka, who is credited with transforming the site into a monumental center of Buddhist devotion. Ashoka is believed to have constructed the first temple at the location, referred to in later texts as the Vajrāsana, or “Diamond Throne”, marking the exact spot of the Buddha’s awakening. Fragments of this Mauryan structure, including polished stone railings and carved sandstone panels, survive and form the oldest datable elements of the current temple complex.

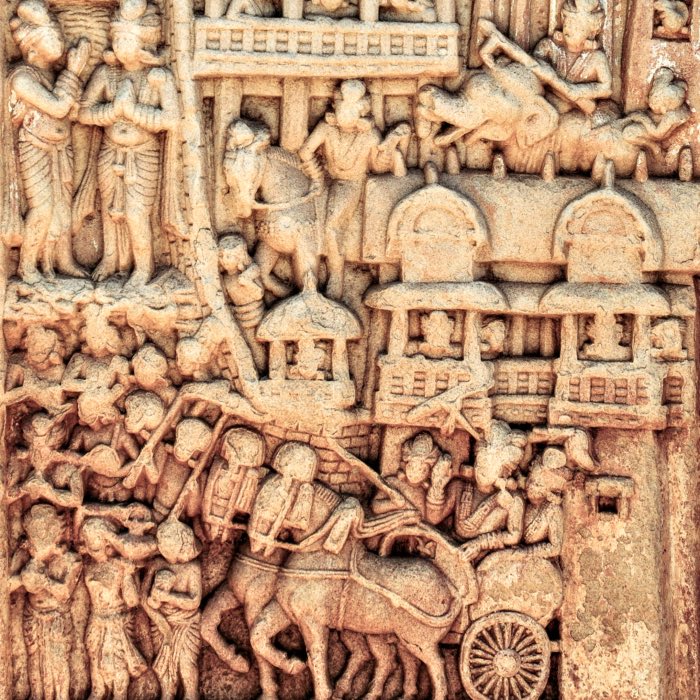

The railings around the temple, some dating to the 2nd century BCE, depict scenes from the Buddha’s life in symbolic, aniconic forms, such as footprints, trees, and thrones. These carvings reflect early doctrinal approaches that avoided direct anthropomorphic representation, and they serve as important material witnesses to the evolution of Buddhist art and theology.

Maha Bodhi Temple, Bodhgaya, India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Importantly, the Bodhi Tree itself has been replanted multiple times through history, yet its symbolic and ritual importance has remained constant. Pilgrims from across the Buddhist world have contributed to the upkeep and reconstruction of the site during various historical periods, including the Gupta, Pāla, and even colonial eras. Inscriptions left by foreign pilgrims such as Faxian and Xuanzang, both traveling monks from China from the 5th and 7th centuries CE respectively, further confirm the site’s longstanding transregional importance.

Great Buddha statue at Bodhgaya, India. The statue is 24 m tall and is located in the Mahabodhi Temple complex, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The statue depicts the Buddha in a meditative posture, symbolizing peace and enlightenment. It was inaugurated in 1989 and has since become a significant pilgrimage site for Buddhists from around the world. The statue is surrounded by beautiful gardens and offers a serene atmosphere for meditation and reflection. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Today, Bodhgayā stands not only as a spiritual landmark but also as a site where tradition and archaeology meet in tangible harmony. Its stratigraphy and architectural evolution attest to a layered history of veneration, imperial patronage, and international pilgrimage. As a result, Bodhgayā offers one of the strongest archaeological validations of a key episode in the canonical life of the historical Buddha.

Sārnāth: First teaching

Sārnāth, located near the sacred city of Vārāṇasī in Uttar Pradesh, holds a central place in Buddhist tradition as the site where Siddhartha Gautama delivered his first sermon following his enlightenment. This event, traditionally known as the “Turning of the Wheel of Dharma” (Dharmacakrapravartana), marks the formation of the Buddhist sangha and the beginning of the public dissemination of his teachings.

View of Sarnath, looking from the ancient Mulagandha Kuty Vihara towards the Dhamek Stupa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

The archaeological remains at Sārnāth are extensive and reflect centuries of religious activity and architectural patronage. One of the most prominent monuments at the site is the Dhamek Stupa, a massive cylindrical structure originally commissioned in the Gupta period (5th–6th century CE) but believed to have been built atop an earlier Ashokan structure. The stupa, nearly 43 meters tall, is made of stone and brick, and features floral and geometric carvings characteristic of later Buddhist art. Its scale and permanence underscore the long-standing importance of this location in the Buddhist world.

The Lion Capital of Ashoka, the Buddha Preaching his First Sermon sculpture, and the Ashokan pillar, along with other antiquities as they appeared upon their exhumation at Sarnath on 15 March 1905 (photograph by F. O. Oertel). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Surrounding the Dhamek Stupa are the foundations of numerous monastic buildings, stupas, and shrines, revealing the complex layout of what was once a thriving monastic center. Excavations at the site have uncovered ruins of ancient viharas (monasteries), a library, and assembly halls, indicating that Sārnāth functioned not only as a pilgrimage site but also as an educational and doctrinal hub for Buddhist practice.

Buddha statue inside a votive stupa at Sarnath. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: Government Open Data License - India (GODL))

Equally important is the discovery of an Ashokan pillar at Sārnāth, which further legitimizes the traditional claim of the site’s importance. Although the pillar is now broken, its base remains in place near the stupa. The pillar originally bore the Lion Capital of Ashoka, which has since been relocated to the Sarnath Museum and serves today as the national emblem of India. The pillar’s inscription, written in Brahmi script, records Ashoka’s visit to the site and his efforts to propagate and institutionalize the Buddha’s teachings.

The convergence of monumental architecture, imperial inscriptions, and literary testimony from pilgrims such as Faxian and Xuanzang make Sārnāth one of the most firmly attested sites in the early Buddhist landscape. It represents the transition from the solitary path of Siddhartha’s personal awakening to the communal and pedagogical dimension of Buddhism. Archaeologically, it offers insight into how Buddhist doctrine was anchored in physical space and how early Buddhist institutions were formed, maintained, and celebrated through imperial patronage and popular devotion.

Rājagaha: Political center and early discourse

Rājagaha (modern-day Rajgir in Bihar) was one of the principal cities during Siddhartha Gautama’s lifetime and served as a significant political and religious center. According to canonical texts, it was here that Siddhartha was received by King Bimbisāra of Magadha, who became one of his earliest royal patrons. Rājagaha’s strategic location in a valley surrounded by hills made it a natural fortress and a political capital before the rise of Pāṭaliputra.

Ruins of the Akhara (place where martial arts are practiced) of king Jarasandha, Rajgir, Bihar. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Archaeologically, the site is rich with remnants of fortifications, stone walls, gateways, and early urban planning, consistent with descriptions of an important early city. The cyclopean walls around the hilltops of Rajgir, made of massive undressed stones, are among the oldest surviving fortifications in India and likely date back to the 6th century BCE, thus overlapping with the purported lifetime of Siddhartha.

The historic locality is surrounded by the Rajgir hills and remains of cyclopean walls. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Two particularly important locations associated with early Buddhism in Rājagaha are Vulture Peak (Gijjhakūṭa) and Venuvana. Vulture Peak is often cited in the suttas as the setting for numerous discourses delivered by the Buddha. Although no major architectural structures survive on the peak itself, its identification is based on consistent literary tradition and geographic continuity. The surrounding area has yielded ruins of rock-cut steps, meditation shelters, and retaining walls that point to long-term monastic use.

Vulture Peak (Pāli: Gijjhakūṭa; Sanskrit: Gṛdhrakūṭa), also known as the Holy Eagle Peak, is a mountain in the Rajgir hills of Bihar, India. It is a significant site in Buddhism, as it is believed to be the place where Gautama Buddha delivered many important teachings and discourses. The peak is associated with various events in the Buddha’s life, including the famous “Sermon at Vulture Peak”. The area around Vulture Peak has been a pilgrimage site for centuries and continues to attract visitors interested in Buddhist history and spirituality. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Venuvana, or the “Bamboo Grove”, was reportedly the first monastery donated to the Buddha and his disciples, offered by King Bimbisāra. While the exact location is uncertain, an identified site bearing this name contains remnants of early brick structures, a water reservoir, and monastic cells, suggesting a planned residential complex consistent with an early vihara.

In addition to these religious sites, Rājagaha’s prominence in the early Buddhist canon underscores its centrality to the social and political dynamics of the time. King Bimbisāra’s documented support for Siddhartha, along with his role in facilitating interactions with other major contemporaneous figures such as Mahāvīra, points to a fertile religious milieu in which Buddhism was one of several emerging spiritual movements.

Together, the archaeological remains and textual associations of Rājagaha support its status as a vital hub of early Buddhist activity. The city’s built environment, royal patronage, and topographical features all reflect its importance in the historical spread of Siddhartha Gautama’s teachings and the consolidation of the early sangha.

Śrāvastī: The longest residence

Śrāvastī, located in present-day Uttar Pradesh, was one of the most important urban centers in ancient India and a key site in the life of Siddhartha Gautama. According to the Buddhist canon, the Buddha spent more rainy seasons here than at any other location, traditionally recorded as twenty-five out of the forty-five years of his teaching life. As such, it was a critical center for the development of early Buddhist thought, monastic practice, and community-building.

View on a section of Jetavana Monastery, Sravasti, India, showing part (the entry) of the Mulagandhakuti, and the Anandabodhi tree in the background. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

The heart of Śrāvastī’s Buddhist heritage is the Jetavana Monastery, donated by the wealthy merchant Anāthapiṇḍika, a prominent lay follower and early patron of the Buddha. The site is traditionally identified with the extensive ruins at Saheth-Maheth, where excavations have revealed a dense and layered complex of monastic buildings, stupas, temples, and courtyards. The remains include structural foundations from the Kushan and Gupta periods, with architectural continuity indicating continuous occupation and religious activity well into the medieval era.

View on a section of Jetavana Monastery, Sravasti, India, showing a collection of smaller stupas, with more large structures in the background. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Among the most striking finds at Jetavana are early brick structures, cells arranged around central courtyards, and a sophisticated water management system. These features point to the site’s importance as a well-organized and resource-rich monastic establishment. Numerous inscribed artifacts, including seals and reliquaries, attest to the monastery’s institutional complexity and the broader network of Buddhist lay and clerical participants who supported it.

Gandhakuti (‘Buddha’s hut’), Jetavana Monastery, Sravasti. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Śrāvastī also holds an important place in Buddhist literature, with many key suttas delivered here. The Anāthapiṇḍikovāda Sutta and numerous Jātaka tales are associated with the setting of Jetavana, which functioned as both a retreat and a public platform for ethical discourse, meditation instruction, and community interaction.

The patronage of figures like Anāthapiṇḍika reflects the deep integration of lay society into the monastic and doctrinal life of early Buddhism. The architectural scale and symbolic placement of buildings within Jetavana underscore the sophisticated interplay between donors, monastics, and political powers that enabled Buddhism to flourish in urban settings.

Stupa of Angulimala, Sravasti. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Taken together, the archaeological and literary evidence from Śrāvastī reinforces its reputation as one of the most vibrant centers of early Buddhist life. Its enduring structures and the richness of its historical associations make it a cornerstone for understanding the lived experience of the early sangha and the material foundations of the Buddha’s long-term residence.

Vaiśālī: Early reforms and women’s ordination

Vaiśālī, located in present-day Bihar, holds a distinguished place in early Buddhist history as both a political and religious center. It was the capital of the Licchavi republic and, according to tradition, a frequent destination of Siddhartha Gautama. Vaiśālī is particularly significant for two major developments in the evolution of the sangha: the ordination of women and the early Buddhist councils that shaped the doctrinal foundations of Buddhism.

Ānanda Stupa, with an Asokan pillar at Kolhua, Vaiśālī. It is said to contain the relics of Ananda, Buddha’s attendant monk and cousin. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

One of the most enduring narratives associated with Vaiśālī is the ordination of Mahāprajāpatī Gotamī, the Buddha’s foster mother and the first woman to be admitted into the monastic order. This event, which marked a revolutionary moment in ancient religious traditions, is believed to have occurred in or near Vaiśālī. Though no direct archaeological evidence confirms the location of this ordination, the tradition is deeply rooted in early texts and commentaries, and Vaiśālī’s status as a progressive and politically autonomous center lends historical plausibility to this event.

Ashoka pillar at Vaishali. Ashoka’s edicts, inscribed on pillars and rock surfaces, highlight the ethical and administrative ideals of the Mauryan state, rooted in the Dharma, the Buddhist concept of moral law. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Archaeological remains at Vaiśālī include a well-preserved Ashokan pillar, topped with a single lion capital, characteristic of Ashoka’s architectural program in the 3rd century BCE. The pillar stands near the site of a stūpa that is traditionally identified as marking the place where the Buddha delivered his final sermon. The presence of the pillar confirms Ashoka’s recognition of Vaiśālī’s importance in the Buddhist sacred geography and his efforts to monumentalize it.

In addition to these imperial markers, the site features numerous stūpas, monastic ruins, and structural remains that suggest a long-standing and vibrant religious community. Of particular note is the relic stūpa believed to have enshrined a portion of the Buddha’s ashes following his cremation. The presence of such a structure indicates Vaiśālī’s early integration into the network of relic veneration that played a central role in Buddhist devotional culture.

Relic Stupa of Vaishali, built by the Licchavis, and possibly the earliest archaeologically known stupa. It is said to contain ashes of Siddhartha Gautama. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Vaiśālī is also associated with the Second Buddhist Council, which was convened approximately a century after the Buddha’s death. This council, held to address disputes about monastic discipline and practice, marks one of the earliest known attempts to codify Buddhist teachings and regulate the sangha. While the council’s exact location within Vaiśālī is unknown and archaeological traces of the gathering are absent, the literary sources naming Vaiśālī as the venue lend additional religious and institutional weight to the site.

The convergence of imperial patronage, monastic activity, and doctrinal consolidation makes Vaiśālī a key node in the early Buddhist world. It reflects both the dynamism of early sangha governance and the inclusive aspirations of the tradition, epitomized in the ordination of women and the attempt to maintain unity through councils. As with other sites, archaeology and tradition intertwine here to illuminate the historical landscape of early Buddhism.

Kuśinagara: Death and relic distribution

Kuśinagara, located in modern-day Uttar Pradesh, is traditionally identified as the site where Siddhartha Gautama passed into paranirvāṇa, the final state beyond suffering. This momentous event — his physical death and spiritual liberation — is commemorated in Buddhist texts as a pivotal transition. As such, Kuśinagara became an early and enduring site of pilgrimage, relic veneration, and imperial patronage.

Ramabhar Stupa in Kushinagara, built over part of the Siddhartha’s ashes on the spot where he was cremated. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

The most prominent structure at the site is the paranirvāṇa Temple, which houses a massive reclining Buddha statue symbolizing the Buddha’s final moments. The current structure and sculpture date to the Gupta period (5th–6th century CE), but archaeological investigations suggest that the site was already significant in the centuries immediately following the Buddha’s death. Excavations have uncovered earlier brick foundations beneath the existing temple, as well as fragments of stupas and platforms that indicate a layered history of ritual use.

Buddha statue at Mata Kuar site. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Nearby stands the Ramabhar Stupa, traditionally believed to mark the cremation site of the Buddha. It is a large, hemispherical mound of bricks with no remaining superstructure, yet its form and dimensions resemble early examples of stūpa architecture. Though its current visible form likely postdates the Buddha by several centuries, archaeological probes have confirmed earlier construction phases. The presence of ash, burnt soil, and charred wood in some strata lends some credence to the association with cremation rites, though direct dating to the time of Siddhartha remains uncertain.

The broader archaeological landscape of Kuśinagara includes monastery ruins, sculptures, and numerous smaller stupas built in later periods, suggesting the area’s continuing importance across centuries. Chinese pilgrims such as Faxian and Xuanzang recorded their visits to the site in the 5th and 7th centuries CE, noting the reverence still paid there and helping later archaeologists identify the location with confidence.

Kuśinagara’s significance lies not only in its association with the historical Buddha’s death but also in what it represents about the Buddhist practice of relic veneration. The cremation and subsequent distribution of the Buddha’s relics formed the basis for the construction of stupas throughout the Indian subcontinent. Kuśinagara is thus not just a memorial but a model for how memory, materiality, and devotion intersect in Buddhist culture. Its archaeological remains reinforce this function by preserving tangible expressions of grief, reverence, and theological continuity.

Synthesis and assessment of historicity

The archaeological exploration of sites associated with the life of Siddhartha Gautama has greatly enriched our understanding of early Buddhism, but it also highlights the methodological boundaries of what archaeology can and cannot achieve. Material evidence, such as inscriptions, structural remains, and stratigraphic data, can affirm the long-standing significance of specific locations, demonstrate the development of religious practices, and align with traditional narratives in meaningful ways. However, archaeology does not directly verify the biographical details of Siddhartha’s life as preserved in canonical texts.

What archaeology can do is corroborate the antiquity and continuity of religious activity at places like Lumbinī, Bodhgayā, Sārnāth, and Kuśinagara. It can establish the plausibility of certain events and offer a physical framework for understanding how sites were revered, repurposed, and monumentalized across time. Inscriptions such as those on Ashokan pillars provide critical epigraphic anchors that connect religious memory with historical rulership, and in some cases, they reference the Buddha directly. These pieces of evidence strengthen the argument that a historical figure named Siddhartha, who later became known as the Buddha, did indeed live and inspire a growing religious community.

At the same time, what archaeology cannot offer is definitive proof of Siddhartha’s internal spiritual journey, his exact teachings as originally spoken, or the precise chronology of his life events. The layers of symbolic and devotional interpretation found at these sites often reflect centuries of evolving religious meaning. The absence of unbroken material continuity between the time of Siddhartha and the earliest extant structures, most of which date from the Mauryan period onward, means that much of what is known about his life remains in the domain of tradition.

Nevertheless, the convergence of literary, archaeological, and epigraphic evidence offers a powerful cumulative case for the historicity of the Buddha and the early formation of the sangha. The emergence of organized monastic complexes, relic veneration practices, and doctrinal councils, many with material traces, suggests a rapid institutionalization of the tradition shortly after the life of its founder.

In sum, archaeology does not dissolve the distinction between myth and history, but it does offer a rigorous lens through which elements of tradition can be evaluated, contextualized, and, in many cases, affirmed. The material record complements textual transmission by grounding abstract teachings and revered memories in physical space, helping us understand how Buddhism moved from a solitary awakening beneath a tree to a global religious civilization.

Conclusion

The archaeological study of sites connected to the life of Siddhartha Gautama provides both compelling confirmations and unavoidable ambiguities. At key locations such as Lumbinī, Bodhgayā, and Sārnāth, material evidence, including Ashokan inscriptions, pre-Mauryan structural remains, and long-standing patterns of ritual use, supports the long-standing tradition that these places were revered from a very early period. These findings lend credibility to the canonical narratives not by verifying their theological claims, but by affirming that they arose in real historical and geographic contexts.

At the same time, many sites, such as Kapilavastu and Kuśinagara, reveal the interpretive limits of archaeology. Disputes over site identification, contested inscriptions, and the often indirect nature of material correlations remind us that archaeology operates with partial evidence and must be interpreted within a broader critical framework. The absence of direct physical artifacts from Siddhartha’s lifetime does not negate his historicity but highlights the challenge of reconstructing a life largely preserved through oral transmission and devotional memory.

Ongoing excavations at existing and newly identified sites continue to refine the historical picture. Innovations in archaeological science such as micro-stratigraphy, isotopic analysis, and geophysical surveying, promise to yield more precise data and perhaps uncover structures and patterns yet unknown. International collaboration and comparative studies across Buddhist regions may also help contextualize early Indian Buddhist sites within a wider religious and cultural history.

The role of scientific archaeology in this domain is not to affirm or deny religious belief but to offer a disciplined inquiry into how religious traditions take shape in space and time. When applied with methodological care and historical sensitivity, archaeology becomes a critical tool for understanding the formation, transmission, and institutionalization of Buddhism. It deepens — not replaces — our understanding of tradition by tracing the physical footprints of ideas that have transformed civilizations.

References and further reading

- Coningham, Robin & Ruth Young, The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE–200 CE, 2023, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521609722

- Trainor, Kevin, Relics, Ritual, and Representation in Buddhism: Rematerializing the Sri Lankan Theravāda Tradition, 1997, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521582803

- Allen, Charles, The Buddha and the Sahibs: The Men Who Discovered India’s Lost Religion, 2003, John Murray, ISBN: 978-0719554285

- Lahiri, Nayanjot, Ashoka in Ancient India, 2015, Harvard University Press, ISBN: 978-0674057777

- Bechert, Heinz (ed.), When Did the Buddha Live? The Controversy on the Dating of the Historical Buddha, 1996, Sri Satguru Publications, ISBN: 978-8170304692

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Hans Wolfgang Schumann, Der historische Buddha: Leben und Lehre des Gotama, 2004, Diederichs, ISBN: 9783896314390

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Robert E. Buswell, William M. Bodiford, Donald S. Lopez, John S. Strong, Eugene Y. Wang, Encyclopedia of Buddhism, 2004, Vol. 1 and 2, Macmillan Reference, ISBN: 978-0028657189

- Keown, Damien, A dictionary of Buddhism, 2003 , Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0-19-860560-7

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

comments