Stūpas: Sacred architecture of Buddhism

The stūpa is one of the most iconic and enduring forms of Buddhist sacred architecture. Emerging from ancient Indian burial traditions, it evolved into a structure that not only houses relics but also embodies the cosmological and spiritual worldview of Buddhism. Unlike conventional buildings, the stūpa is not meant to be entered. It is meant to be circumambulated, meditated upon, and venerated, making it as much a ritual space as an architectural form.

The Great Stupa at Sanchi. The stūpa consists of a hemispherical dome (anda) and a square base (harmikā), topped by a spire (chattra). The stūpa is surrounded by a stone railing and four gateways, or toranas (built from the 1st c. BCE to the 1st c. CE), which are richly decorated with reliefs depicting scenes from the life of the Buddha and Jātaka tales. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Over centuries, the stūpa has served multiple roles: a reliquary for the remains of the Buddha and other enlightened figures, a symbol of enlightenment itself, and a focal point for communal and devotional activity. Its significance extends beyond its physical design, integrating symbolism, ritual, and identity across Buddhist traditions.

This post aims to offer a historical and architectural overview of the stūpa, tracing its development from ancient India to its regional adaptations across Asia. It also examines how the stūpa functions as a medium of religious expression and cultural continuity within the broader Buddhist world.

Origins and early development

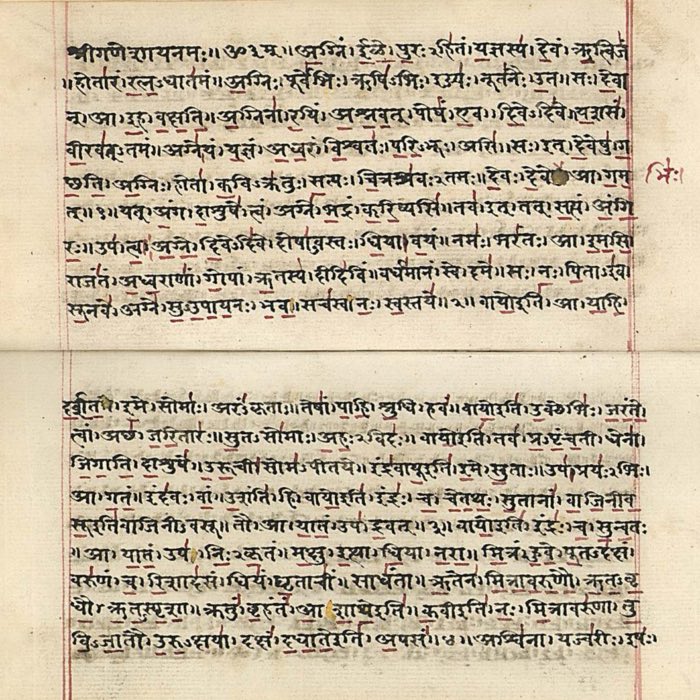

The origins of the stūpa are deeply rooted in pre-Buddhist burial practices of the Indian subcontinent. In Vedic and other early Indic traditions, cremated remains of important individuals were interred in mounds or tumuli, often marked by stones or earthen constructions. These ancestral mounds were sites of reverence and memorial rituals, reflecting a cultural continuity in funerary veneration that would later be adapted by Buddhist communities.

Relic Stupa of Vaishali, built by the Licchavis, and possibly the earliest archaeologically known stupa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

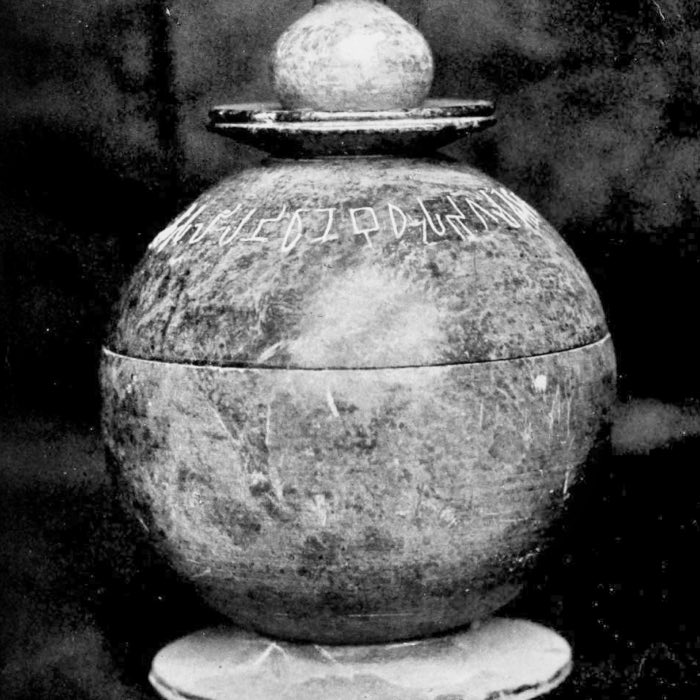

The transformation of the funerary mound into the distinctively Buddhist stūpa began with the paranirvāṇa (final passing) of Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha, around the 5th century BCE. According to the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta, his cremated remains were divided among eight claimant groups, including the Śākyas of Kapilavastu and several powerful republics and kingdoms. Each group constructed a mound to house their share of the relics, giving rise to the first eight stūpas.

The Piprahwa stupa is one of the earliest surviving stupas. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

This initial act of relic enshrinement laid the foundation for a ritual and architectural tradition that would become central to Buddhism. The stūpa served as both a reliquary and a symbol of the Buddha’s ongoing spiritual presence. The practice was dramatically expanded during the reign of Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE, who, according to legend, redistributed the original relics into 84,000 stūpas across his vast empire. While the precise number may be symbolic, Ashoka’s historical role in spreading Buddhism and commissioning monumental architecture is well-attested in both inscriptions and archaeological remains.

Thus, the early stūpa was born from a confluence of ancient funerary traditions, doctrinal reverence for the Buddha’s body, and imperial support. It quickly evolved into one of Buddhism’s most recognizable and meaningful forms of sacred architecture.

Symbolism and cosmology

Beyond their architectural function, stūpas are imbued with profound cosmological and symbolic meanings in Buddhist traditions. The stūpa is often understood as a three-dimensional mandala, a sacred diagram that represents the Buddhist universe. Its form is not merely aesthetic or commemorative, but reflects deep metaphysical ideas about reality, the path to awakening, and the structure of the cosmos.

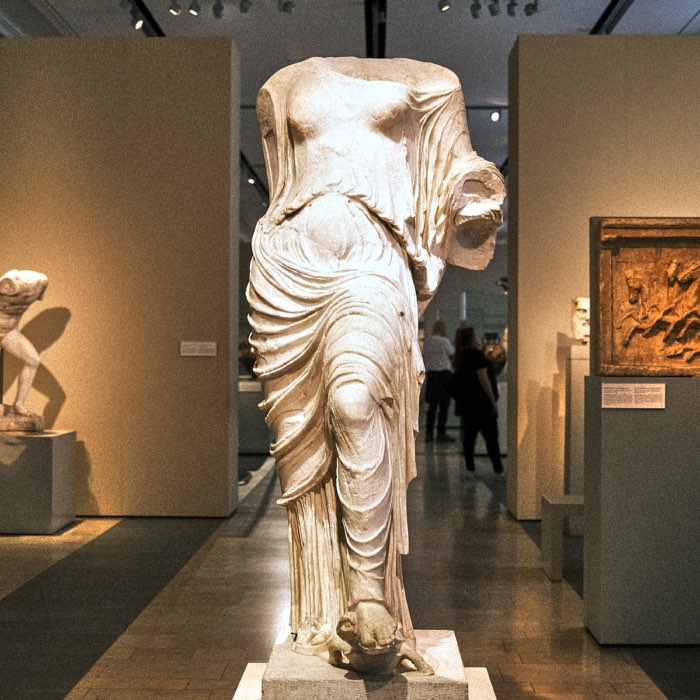

Adoration of a stupa, Central India, Sanchi, 1st c. CE, sandstone, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin. Before anthropomorphizing the Buddha, the stūpa was a symbol of the Buddha’s presence and was often adorned.

Adoration of a stupa, Central India, Sanchi, 1st c. CE, sandstone, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin. Before anthropomorphizing the Buddha, the stūpa was a symbol of the Buddha’s presence and was often adorned.

At its most basic level, the stūpa symbolizes the body of the Buddha, and by extension, the potential for enlightenment that resides in all beings. Its components correspond to aspects of the path: the square base represents mindfulness and moral discipline; the dome (anda) signifies the boundless sky or the infinite nature of the Dharma; the harmikā and chattra at the top stand for spiritual realization and the stages of awakening.

In many traditions, stūpas are said to embody the five great elements (mahābhūta):

- earth (base),

- water (dome),

- fire (spire),

- air (umbrella discs), and

- space (the void within and around the structure).

This elemental layering not only anchors the stūpa in physical cosmology but also underscores the doctrine of impermanence and interdependence.

A vertical axis, rising from the base through the relic chamber and culminating in the finial, symbolizes Mount Meru, the mythological center of the Buddhist universe. At the very heart of the stūpa lies the relic or symbolic core, considered a spiritual nucleus from which blessings emanate. This centrality is both physical and doctrinal: the relic enshrined at the center is not only a sacred object but a focal point for meditative visualization and cosmic alignment.

In this way, the stūpa becomes a sacred center, where spatial geometry, ritual practice, and cosmological vision converge. Pilgrims walking clockwise around the stūpa (pradakṣiṇā) are not merely performing a devotional act. They are also moving within and in relation to a symbolic universe, aligning body and mind with the Dharma.

Architectural structure and regional variations

Despite regional diversity, most stūpas share a set of fundamental architectural features that symbolize elements of the Buddhist path and cosmology. The anda or dome represents the womb of the universe and often houses the relic chamber. Rising above it is the harmikā, a square enclosure symbolizing the celestial realm, which supports the chattra, a series of umbrella-like discs representing stages of spiritual attainment or the protection of the Dharma. The entire structure is surrounded by toranas (ornamental gateways) and a pradakṣiṇā path, used for ritual circumambulation. These components reflect a balance of spiritual metaphor and practical devotional use.

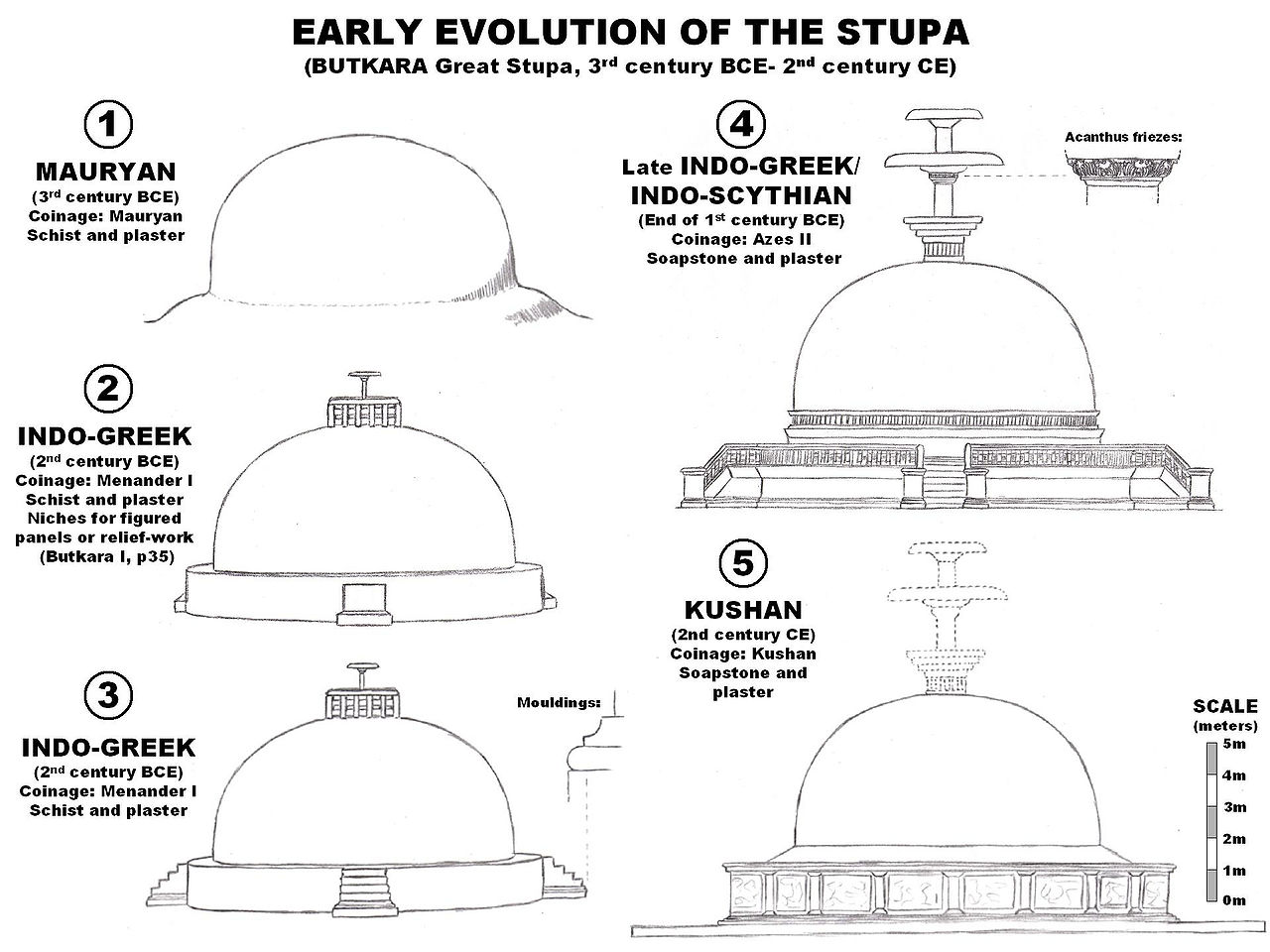

Evolution of the Great Stupa at Butkara, Gandhara, 3rd c. BCE to 2nd c. CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Over time, stūpa architecture diversified significantly across the Buddhist world, adapting to regional styles, materials, and symbolic emphases while retaining core elements of form and function:

- Indian stūpas, such as those at Sanchi, Bharhut, and Amaravati, emphasize large hemispherical domes and intricately carved railings and gateways. These early examples are among the best-preserved and most richly decorated, serving as models for later forms.

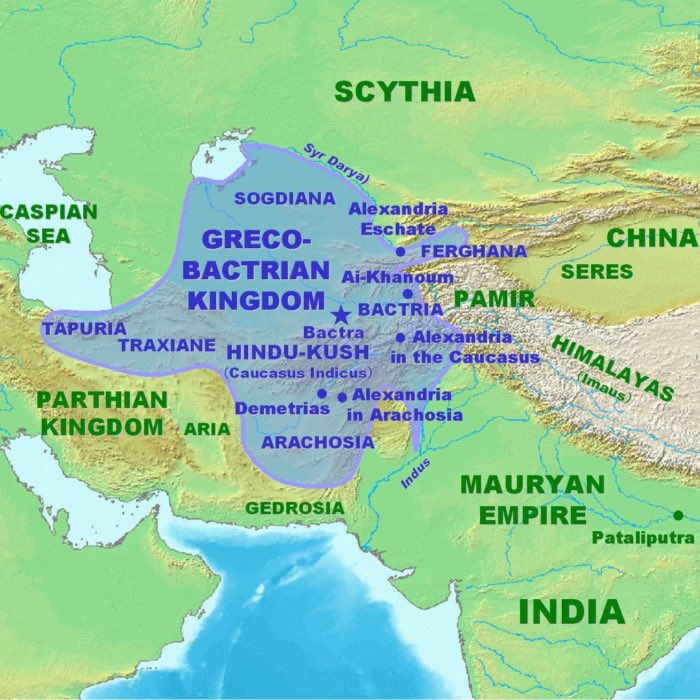

- Gandhāran and Central Asian stūpas reflect Greco-Roman artistic influences, with elongated drums and decorative niches housing Buddha images. Their location along the Silk Road facilitated cross-cultural architectural exchanges.

- Sri Lankan dagobas are characterized by their massive size and smooth white domes, such as the Ruwanwelisaya and Jetavanaramaya in Anuradhapura. These structures often feature square bases and prominent chattra spires, emphasizing royal patronage and centralized religious authority.

- Tibetan chörtens (also called stupas) vary in form depending on their symbolic function, often built in accordance with the “Eight Great Stūpas” typology commemorating key events in the Buddha’s life. Tibetan stupas commonly incorporate tantric symbolism and are often richly painted or adorned with prayer flags.

- Southeast Asian stupas, such as those in Myanmar (e.g., Shwedagon Pagoda), Thailand (e.g., Wat Phra That Doi Suthep), Laos (e.g., That Luang), and Cambodia (e.g., Wat Phnom), often take slender, spire-like forms. These may be covered in gold or other reflective materials, symbolizing the radiance of enlightenment.

Sanchi Stupa No.2, the earliest known stupa with important displays of decorative reliefs, c. 125 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

This regional adaptation demonstrates the stūpa’s capacity to serve as both a universal symbol of the Dharma and a culturally localized expression of Buddhist art and devotion.

A stūpa representing Mount Meru, the center of the universe in Buddhist cosmology, at the temple complex of Wat Mahathat, Sukhothai, Thailand. The stūpa’s design reflects both Indian influences and local architectural traditions, showcasing the syncretic nature of Buddhist art in Southeast Asia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Abhayagiriya Stupa in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

An early stupa at Guntupalle, probably Maurya Empire, 3rd c. BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Chorten near Potala Palace, Lhasa, Tibet. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Jetavanaramaya in Sri Lanka, the tallest stupa in the ancient world. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The stūpa’s transformation into the pagoda

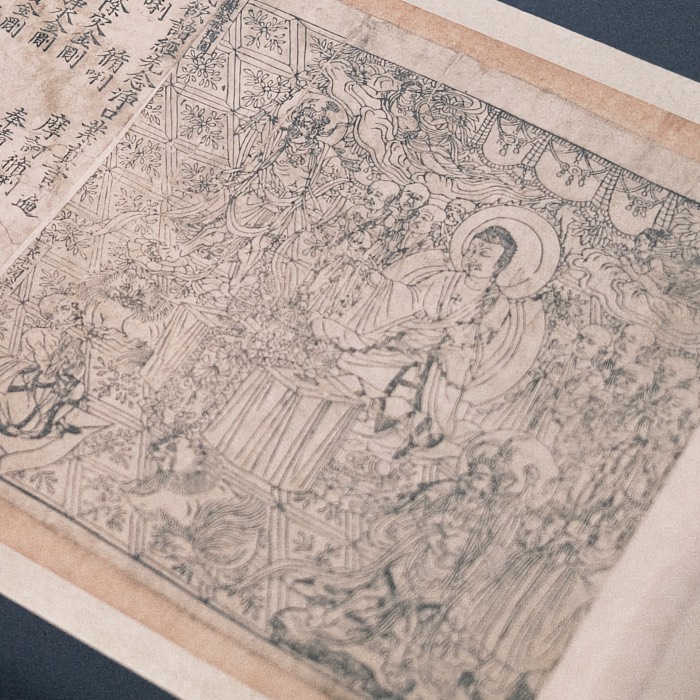

One of the most striking developments in Buddhist architecture occurred with the transformation of the Indian stūpa into the multi-storied pagoda form in East Asia. As Buddhism spread along trade and pilgrimage routes into China, Korea, and Japan, the stūpa was reinterpreted through the lens of local building traditions, especially timber construction and multi-tiered tower architecture.

The Xumi Pagoda, built in 636 CE during the Tang dynasty. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

In China, the pagoda evolved under the influence of both Buddhist symbolism and native architectural forms such as watchtowers and Taoist shrines. Early Chinese pagodas, often made of wood and later brick, preserved the stūpa’s function as a reliquary but expressed it in vertical, ascending tiers. These levels were interpreted as stages of spiritual ascent or as symbolic of the Buddhist cosmos.

The 40-metre-tall Songyue Pagoda of 523 CE, the oldest extant stone pagoda in China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

In Korea, pagodas retained the verticality and symbolism of Chinese forms but were often constructed in stone and on a more compact scale. Iconic examples such as the three-storied pagoda at Bulguksa Temple highlight the Korean emphasis on geometric clarity and integration into temple layouts.

Bunhwangsa Pagoda, Gyeongju, South Korea. The pagoda is a three-story stone structure built in the 7th century CE, reflecting the influence of Chinese and Indian architectural styles. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

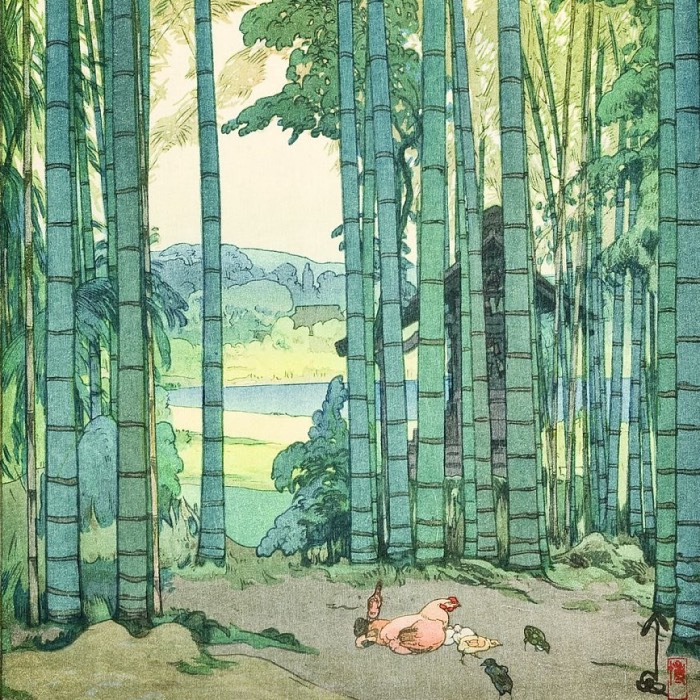

Japanese pagodas similarly preserved the stūpa’s symbolic intent while adopting local design preferences. The typical five-story Japanese pagoda reflects the five elements (earth, water, fire, wind, and space) and serves as a visual representation of the Dharma’s universality. While many Japanese pagodas are now part of Shingon and Tendai temple complexes, their origins are firmly rooted in earlier Buddhist funerary and devotional practices.

Five-story pagoda of Mount Haguro, Japan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Across these East Asian cultures, the transformation of the stūpa into the pagoda represents both continuity and innovation, preserving the sacred center of relic enshrinement while allowing form to evolve in dialogue with new environments and aesthetic sensibilities. The pagoda stands today as a uniquely East Asian expression of Buddhist sacred space, with its roots still traceable to the ancient Indian stūpa.

Ritual, worship, and social function

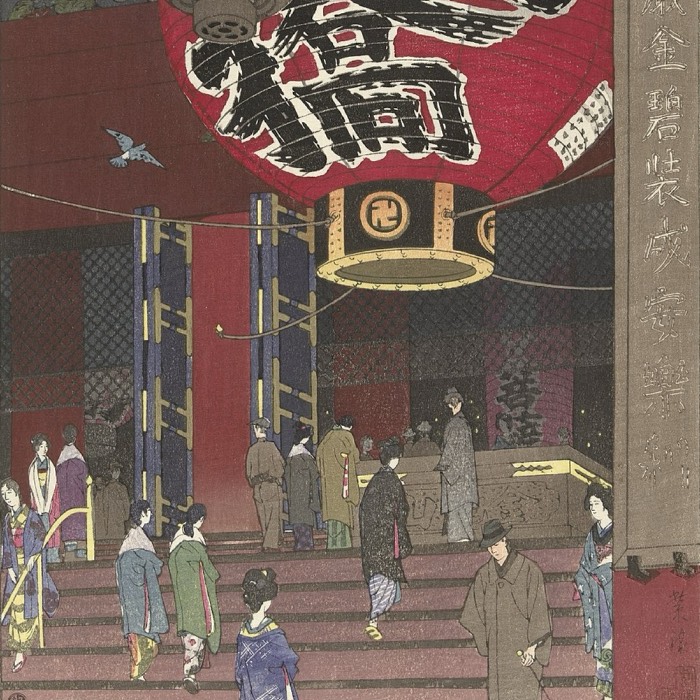

Stūpas serve as dynamic centers of ritual practice and communal worship across Buddhist cultures. One of the most prominent devotional activities associated with the stūpa is circumambulation (pradakṣiṇā), in which practitioners walk clockwise around the structure. This act is deeply symbolic: it reflects the cyclical nature of existence and aligns the devotee with the Dharma through embodied movement. Circumambulation is often performed while reciting mantras or prayers, and is believed to accumulate puṇya, or merit, which supports spiritual progress and favorable rebirths.

Stūpas also play a significant role in monastic life and festival cycles. Major festivals such as Vesak (Buddha’s birth, enlightenment, and paranirvāṇa) or relic veneration days draw large numbers of monastics and laypeople to the stūpa, where rituals, chanting, and offerings are performed. Monasteries often incorporate stūpas as central features of their sacred geography, reinforcing the presence of the Buddha and providing focal points for daily acts of veneration.

Beyond monastic contexts, stūpas function as a key medium for lay devotion, merit-making, and acts of generosity. Laypeople make offerings, such as candles, incense, flowers, and textiles, to the stūpa as a way to express reverence and accumulate merit. Financial and material donations are also common, contributing to the construction, maintenance, or restoration of stūpas. Throughout history, royal patronage has played a crucial role in stūpa development, with kings and emperors commissioning grand structures as expressions of piety, political legitimacy, and religious merit. Such acts served both spiritual and political functions, embedding the stūpa within the socio-religious fabric of Buddhist society.

Evolution over time

The evolution of the stūpa reflects the dynamic interplay between changing religious ideologies, artistic innovation, and political patronage across Buddhist cultures. Originally conceived as simple relic mounds, stūpas were intended to house the cremated remains of the Buddha and prominent disciples. These early forms were modest in structure but sacred in meaning, serving as tangible connections to the Buddha’s spiritual presence and a focus of veneration for the early saṅgha.

Over time, however, stūpas underwent a significant transformation into symbolic monuments — structures not only defined by their function as reliquaries but also by their capacity to convey profound doctrinal, cosmological, and narrative meanings. They began to incorporate inscriptions, narrative reliefs, and architectural refinements, evolving into visual sermons and embodiments of Buddhist philosophy. Monumental examples like the Great Stūpa at Sanchi exemplify this shift, featuring elaborate stone railings and sculptural panels that narrate Jātaka tales and key episodes from the Buddha’s life.

In addition to their role as reliquaries, stūpas became narrative vessels and political instruments. Rulers and patrons used stūpa construction to legitimize power, demonstrate piety, and foster unity within their realms. The stūpa thus became both a religious and civic symbol — an emblem of the Dharma and of political sovereignty. This dual function is evident in the actions of rulers such as Ashoka in India, Anawrahta in Myanmar, and Songtsen Gampo in Tibet.

As Buddhism spread and diversified, stūpas were increasingly integrated into temple complexes and adapted according to regional and sectarian needs. In Mahāyāna contexts, stūpas came to symbolize the universal Buddha-nature and the goal of full awakening, often incorporating symbolic representations rather than physical relics. In Vajrayāna Buddhism, especially in Tibet and the Himalayas, stūpas (chörtens) gained esoteric dimensions, serving as ritual mandalas, mnemonic devices for tantric teachings, and aids in meditation and visualization practices. Their architecture was codified into specific types, such as the Eight Great Chörtens, each commemorating a pivotal moment in the Buddha’s life.

Thus, from humble funerary origins, the stūpa evolved into a complex and multifunctional symbol: a reliquary, a didactic medium, a political monument, and a ritual centerpiece. Its adaptability across regions and epochs testifies to its central role in the architectural, devotional, and ideological history of Buddhism.

Modern rediscovery and conservation

The modern rediscovery of ancient stūpas owes much to the efforts of colonial archaeologists and scholars, particularly during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Under British colonial rule in India, figures such as Alexander Cunningham and James Fergusson began systematic documentation of Buddhist monuments. These efforts were driven by a combination of antiquarian interest, imperial curiosity, and nascent academic disciplines like archaeology and art history. Major sites such as Sanchi, Amaravati, and Bharhut were surveyed, excavated, and, in some cases, partially reconstructed. Their findings, published in detailed reports and illustrated volumes, sparked global scholarly interest in Buddhist heritage and contributed to the formation of Buddhist studies as a modern field.

Alongside excavation, restoration practices emerged as a central concern. Many stūpas had suffered from centuries of neglect, environmental degradation, or human repurposing. Restoration efforts, initiated both during and after the colonial period, aimed to preserve these structures and sometimes to rebuild them based on archaeological inference and textual evidence. While early restorations were often criticized for being speculative or intrusive, later efforts embraced more rigorous standards of conservation. Institutions such as UNESCO and national archaeological departments began overseeing preservation with an emphasis on historical integrity, cultural sensitivity, and sustainable tourism.

The 20th century also witnessed a global revival of Buddhism, which paralleled and supported stūpa restoration and construction. As Buddhist communities reasserted their heritage and identity in the face of colonial disruption and modern secularization, stūpas became potent symbols of cultural resilience and spiritual continuity. International figures like Anagarika Dharmapala and organizations such as the Maha Bodhi Society played a key role in reconnecting diasporic and global Buddhists to ancient sacred sites. New stūpas were built as acts of devotion and unity, often with international collaboration, reflecting the transnational nature of contemporary Buddhism.

In the present day, contemporary Buddhist architecture continues to draw inspiration from the stūpa form. Modern stūpas are erected not only in traditional Buddhist regions but also in the West and other global contexts, adapting to local materials and aesthetic preferences while retaining symbolic fidelity. Examples include the Peace Pagodas built by the Nipponzan Myōhōji order across several continents, and modern temples in urban centers where the stūpa anchors meditation gardens or interfaith spaces. In this way, the stūpa remains a living tradition, revered as much for its spiritual symbolism as for its architectural elegance and historical legacy.

Conclusion

The stūpa stands as one of the most enduring and multifaceted symbols of Buddhism. From its origin as a funerary mound to its role as a reliquary, cosmological diagram, artistic monument, and devotional focal point, the stūpa has served as a tangible expression of Buddhist teachings and aspirations. Religiously, it embodies core doctrines such as impermanence (anatta), the path to awakening (magga), and the continuing presence of the Buddha. Artistically, its evolution across regions has given rise to a diverse yet thematically unified architectural tradition, one that bridges narrative, symbolism, and sacred geometry. Historically, the stūpa reflects the transmission and transformation of Buddhism across time, shaped by cultural exchange, political patronage, and spiritual innovation.

Boudhanath Stupa, Kathmandu, Nepal. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

As a living tradition, the stūpa links past and present. Whether standing in ancient ruins, restored heritage sites, or newly built temples, it functions as a site of memory and aspiration. For Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike, the stūpa remains a focal point for understanding how architecture can express a worldview, preserve a legacy, and inspire ongoing engagement with the intellectual and spiritual heritage of Buddhism.

References and further reading

- Snodgrass, Adrian, The Symbolism of the Stupa, 1992, Motilal Banarsidass Publications, ISBN: 978-8120807815

- Huntington, Susan L., The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, 1985, Weatherhill, ISBN: 978-0834801837

- Dehejia, Vidya, Indian Art, 1997, Phaidon Press, ISBN: 978-0714834962

- Strong, John S., Relics of the Buddha, 2024, Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House, ISBN: 978-9359035284

- Coningham, Robin & Ruth Young, The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE–200 CE, 2023, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521609722

- Bandaranayake, Senake, Sinhalese Monastic Architecture: The Viháras of Anurádhapura, 1997, Brill, ISBN: 978-9004039926

comments