Sīla – Buddhist ethics: The path of moral cultivation

Buddhist ethics, as explored in this article, builds directly upon the framework of the Noble Eightfold Path (Ariyo Aṭṭhaṅgiko Maggo), particularly its ethical dimension (sīla). While the Eightfold Path provides the structural foundation for ethical conduct, this post deepens the inquiry by examining Buddhist ethics as a form of virtue cultivation, character development, and compassionate responsiveness to suffering. It expands the understanding of ethical practice beyond basic precepts into a broader vision of personal transformation and universal compassion.

Expanding upon this foundation, the ethical vision in Buddhism presents a comprehensive framework for moral, psychological, and existential development. Unlike many Western ethical systems, which are often based on divine commandments, social contracts, or utility calculations, Buddhist ethics is deeply rooted in the interdependent concepts of karma, intentionality (cetanā), wisdom (prajñā), and compassion (karuṇā). It emphasizes the gradual cultivation of character through sustained practice, the refinement of mental dispositions, and the experiential realization of impermanence (anicca), non-self (anattā), and dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda). Ethical conduct is not merely a matter of conforming to rules but arises naturally from the transformation of perception and volition. It serves as a foundation for calming the mind, minimizing suffering, dissolving the boundary between self and other, and progressing toward liberation from cyclic existence (saṃsāra). In this post, we explore the foundations of Buddhist ethics, its expression through frameworks like the Five Precepts, the Brahmavihāras, and the Bodhisattva ideal, and its relevance as a model for ethical living in both ancient and contemporary contexts.

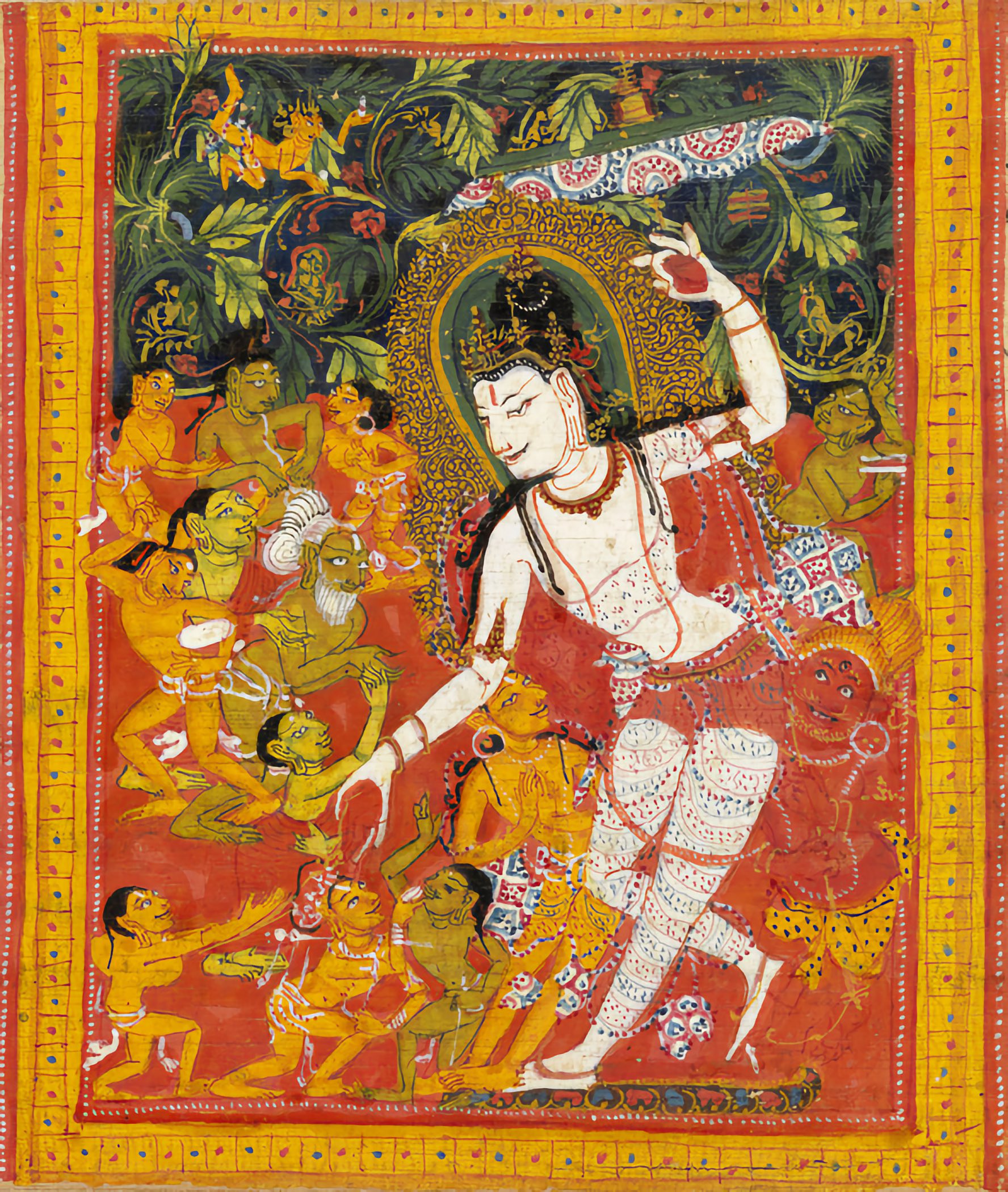

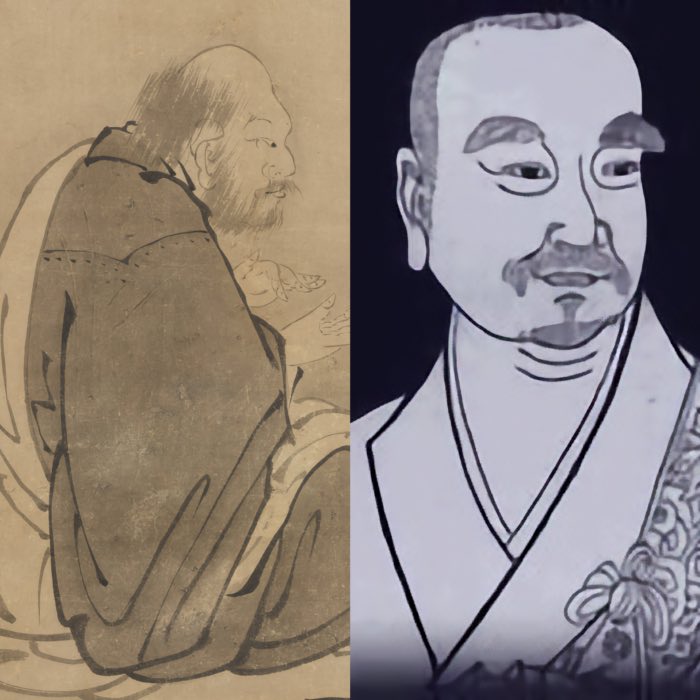

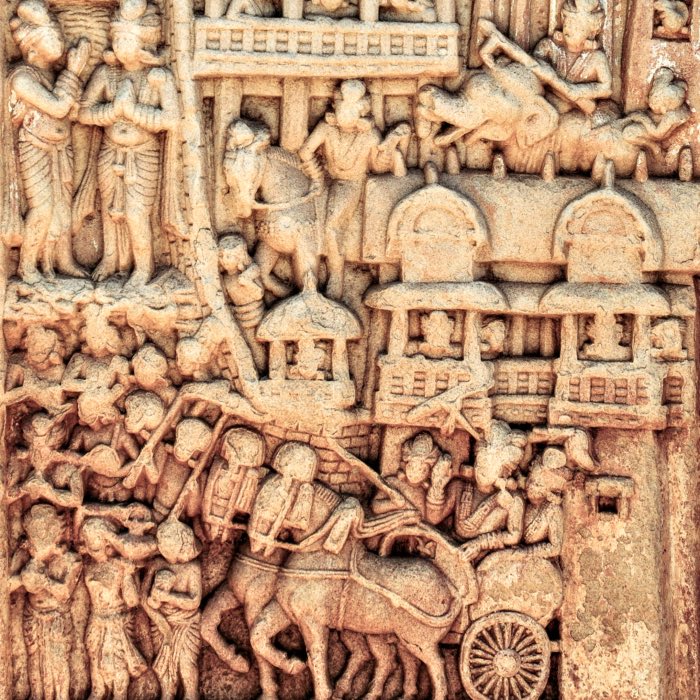

Depiction of a bodhisattva benefiting sentient beings, from a Sanskrit Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra manuscript in Rañjanā script, India, early 12th century. The bodhisattva, central to Mahāyāna Buddhist ethics, vows to postpone personal liberation in order to alleviate the suffering of all beings. This visual representation reflects a moral ideal rooted not in obligation, but in insight, empathy, and the deep realization of interdependence. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Depiction of a bodhisattva benefiting sentient beings, from a Sanskrit Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra manuscript in Rañjanā script, India, early 12th century. The bodhisattva, central to Mahāyāna Buddhist ethics, vows to postpone personal liberation in order to alleviate the suffering of all beings. This visual representation reflects a moral ideal rooted not in obligation, but in insight, empathy, and the deep realization of interdependence. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The foundations of Buddhist ethics

The moral system within Buddhism is underpinned by the concept of karma: the idea that intentional actions — those of body, speech, and mind — carry consequences that shape both current and future experiences. Ethical behavior is understood not as obedience to divine will, but as participation in a natural causal order. Actions imbued with greed, hatred, or delusion are said to lead to suffering, while those motivated by generosity, compassion, and clarity are thought to lead toward liberation. This entire framework finds structured expression within the Noble Eightfold Path, where ethical conduct (sīla) constitutes one of the three pillars of spiritual cultivation. The specific dimensions of sīla — Right Speech, Right Action, and Right Livelihood — serve as practical applications of the core Buddhist principle: to act in ways that reduce suffering for oneself and others.

One of the most widely cited ethical formulations is the set of Five1 Precepts (pañca sīla), guidelines representing a condensed version of Buddhist ethical teachings:

- To refrain from killing – This extends beyond the prohibition of murder and includes the fostering of a nonviolent attitude.

- To refrain from stealing – Respecting the property and autonomy of others is key.

- To refrain from sexual misconduct – Behavior that causes harm through sexuality is to be avoided.

- To refrain from false speech – Ethical communication is emphasized, including the avoidance of lying and malicious speech.

- To refrain from intoxicants – Substances that impair clarity and moral discernment are discouraged.

These Five Precepts embody Siddhartha Gautama’s foundational ethical principle: to act in ways that avoid causing suffering to oneself and others. They translate this abstract principle into practical instructions, illustrating a simple yet often ignored truth: existence is permeated by suffering, both for ourselves and for others. We are all entangled in suffering, not only as victims but also as contributors. Each of us plays a role in perpetuating suffering in the world. Beings suffer, and some suffer because of us. The Five Precepts represent a conscious response to this reality. They invite us to reflect on how our way of living may contribute to the proliferation of suffering and to consider how we might alter our conduct to avoid doing so.

Moreover, the principle of Right Livelihood (sammā-ājīva) carries an important ethical nuance: not all individuals have equal opportunities to lead ethically optimal lives. Poverty, illness, and systemic barriers often constrain people’s choices. Someone with a stable office job in an affluent society finds it easier to live according to moral standards than someone struggling to survive by collecting plastic bottles in a West African slum. Acknowledging the role of conditions in shaping ethical possibilities fosters a compassionate understanding: ethical expectations must be tempered by an awareness of the diverse circumstances people face.

Buddhist ethics as a virtue ethics

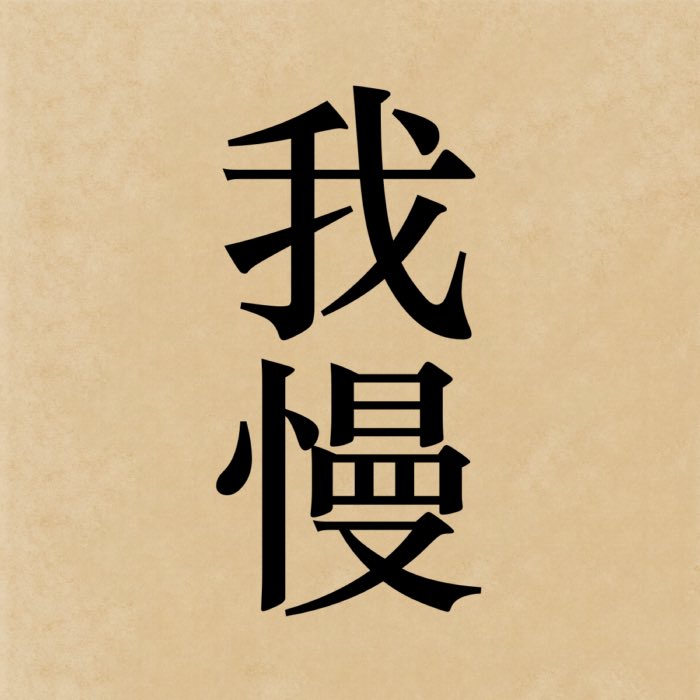

The Noble Eightfold Path is referred to as a “path” precisely because it outlines a long-term, transformative journey. It serves the cultivation of a new mental attitude, a process that inevitably demands time, energy, and perseverance. Genuine transformation cannot be achieved through intellectual understanding alone or by reading a few books; it requires steady, sustained practice over years. The ethical development envisaged in Buddhist virtue ethics thus rests fundamentally on consistent, long-term cultivation.

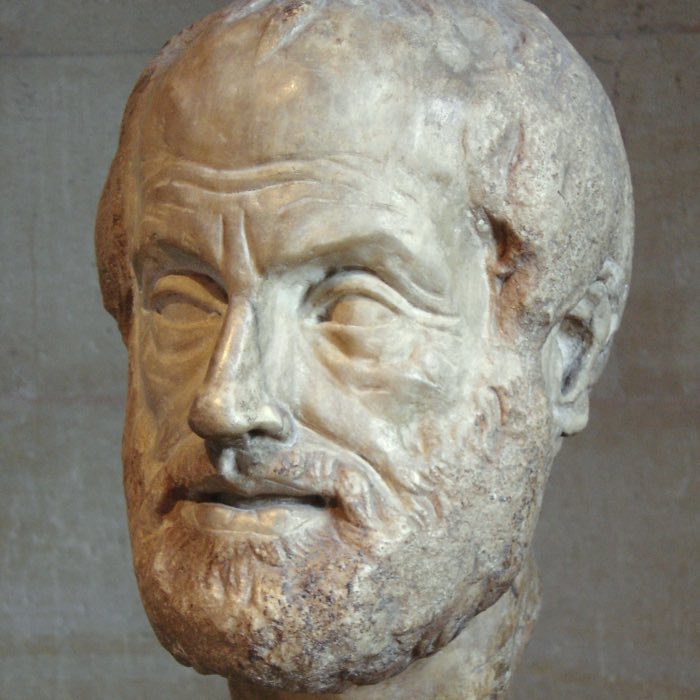

Unlike rule-based ethical systems that prioritize the question “What should I do?”, virtue ethics centers on the question “What kind of person should I become?” In Buddhist ethics, as in ancient and medieval philosophies such as those of Aristotle, Confucius, and Thomas Aquinas, the focus lies on cultivating character traits that predispose a person to act rightly in complex, real-world situations. Siddhartha’s ethics can be understood within this tradition of virtue ethics.

Virtues are stable dispositions of character, guiding individuals to act appropriately without needing external compulsion. Aristotle describes virtue (exis) as a positive character trait leading one to act rightly when circumstances demand it. Similarly, in Buddhism, ethical qualities become ingrained through repeated, conscious choices. Just as a glass is fragile because it tends to shatter when dropped, a generous person naturally acts generously when opportunities arise.

Virtues are not innate but are developed through deliberate practice and habituation. One becomes a skilled craftsperson by carefully practicing their craft; similarly, one becomes compassionate by repeatedly practicing compassion. Over time, isolated decisions consolidate into stable traits that shape future behavior spontaneously.

In this light, the Noble Eightfold Path presents not a rigid set of commandments but a developmental framework for transforming character. It provides an answer to the questions “What kind of person should I become?” and “What kind of life should I lead?” Ethical conduct (sīla), mental cultivation (samādhi), and wisdom (paññā) jointly form a process to overcome the egoistic dispositions rooted in the illusion of selfhood. Through this transformation, one gradually weakens attachment and the craving that perpetuates suffering.

The Eightfold Path is thus a practical response to the insight into non-self (anattā) and dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda). Ethical conduct arises not from external enforcement but from the natural unfolding of a well-trained character. When one genuinely realizes that all beings share the wish to be free from suffering, the impulse to harm or exploit others diminishes naturally. Thus, ethical behavior becomes the spontaneous expression of an awakened character, not an obligation imposed by external authority.

Ethics as a path to liberation

Buddhist ethical teachings, while rooted in virtue cultivation, are not aimed at virtue as an end in itself. Rather, they are embedded within a soteriological framework: virtues are cultivated as an essential part of the path toward liberation from suffering (dukkha). Ethical conduct (sīla) is one of the three core disciplines in Buddhism and forms part of the Noble Eightfold Path (Ariya-aṭṭhaṅgika-magga), specifically grouped with Right Speech (sammā-vācā), Right Action (sammā-kammanta), and Right Livelihood (sammā-ājīva). These are understood not merely as social behaviors but as practices intended to align one’s actions with a deeper internal clarity and intentional discipline. They are structurally interdependent with mental concentration (samādhi) and wisdom (paññā, Sanskrit: prajñā), forming a comprehensive approach to spiritual development known as the Threefold Training (tisikkhā).

Brahmavihāras

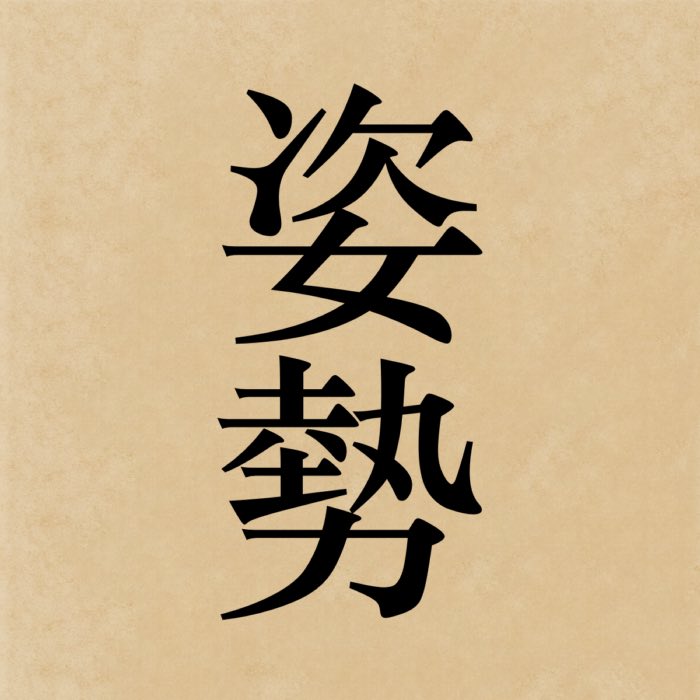

The long-term cultivation of character along the Buddhist path aims at integrating the deep insights into impermanence (anicca), non-self (anattā), and the origin of suffering (dukkha) into one’s entire being. The resulting character is marked by the dissolution of ego-centered tendencies and a selfless responsiveness to the world. In such a character, the distinction between one’s own suffering and the suffering of others fades, giving rise to a naturally compassionate and ethically attuned way of living.

This transformation is concretely expressed in the development of the four “sublime attitudes” or Brahmavihāras:

These are not fleeting emotional states but stable dispositions of character that embody a non-egocentric perspective on reality.

Loving-kindness (mettā) refers to an unconditional, impartial attitude of goodwill toward all beings, regardless of proximity or personal relationship. Unlike everyday forms of affection, which often carry hidden self-interest or preferential bias, mettā is grounded in the recognition that all beings wish to be free from suffering. It is not based on attachment or desire, but on a profound, unbiased benevolence. Cultivating mettā involves expanding the natural concern we might feel for close ones to encompass all sentient beings, without expectation of reward or reciprocation.

Compassion (karuṇā) complements mettā by focusing specifically on the suffering of others. True compassion acknowledges suffering without judgment or blame and is accompanied by the genuine wish and active intention to alleviate it. It is distinguished from emotional contagion or helpless sorrow; rather, karuṇā is a lucid, courageous engagement with the reality of suffering, rooted in the insight that there is no fundamental difference between oneself and others. In this way, compassion becomes the antidote to the habitual egoistic tendency to ignore, minimize, or justify the suffering of others.

Sympathetic joy (muditā) is the capacity to rejoice in the happiness and success of others without envy or resentment. It reflects a liberation from the self-centered impulse to measure one’s own worth against others or to begrudge their fortune. Like compassion, muditā is based on the recognition that others’ joy is as real and valid as one’s own and that joy itself is a movement away from suffering. Cultivating muditā involves training the heart to delight in goodness wherever it arises.

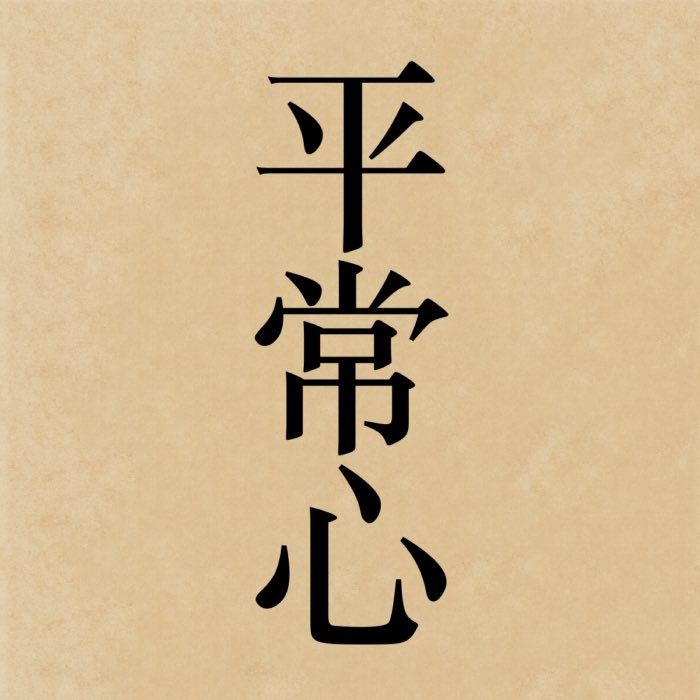

Equanimity (upekkhā) represents a deep, stable serenity in the face of life’s fluctuations. It is the culmination of insight into the impermanent and impersonal nature of phenomena. Upekkhā does not mean indifference or emotional numbness; rather, it signifies a realistic acceptance of the changing conditions of existence without clinging or aversion. This even-mindedness extends to oneself and to others equally, breaking the habitual privileging of one’s own happiness and misfortune. Through equanimity, one ceases to view the world from the distorted perspective of self-centered concern, responding instead with balance and wisdom.

Each of the Brahmavihāras represents a particular facet of a character freed from the illusions of fixed identity and egocentric craving. Together, they form a comprehensive ethical and emotional orientation, aligning the practitioner’s inner life with the fundamental truths recognized through Buddhist insight. They are not commandments to be followed under external compulsion, but natural expressions of an awakened character – manifestations of seeing reality as it truly is.

The role of compassion

Beyond its cultivation as an ethical virtue within the framework of the Brahmavihāras, compassion (karuṇā) occupies a pivotal role in Buddhist thought as an existential and cognitive condition for liberation from suffering (dukkha). It reflects not merely a moral quality but an insight-driven transformation of perception: the dissolution of the boundary between self and other through the recognition of interdependence and non-self (anattā). Compassion thus arises not from obligation or sentimentality, but from wisdom itself.

Compassion (karuṇā) in Buddhist thought is not merely a strategic method (upāya) or a doctrinal duty; it constitutes a fundamental existential and cognitive condition for liberation from suffering (dukkha). From this perspective, the aspiration for personal liberation alone proves insufficient if one remains emotionally attuned to the suffering of others. This is because the enduring presence of others’ suffering undermines the stability and completeness of one’s own happiness and peace; as long as others continue to suffer, empathetic awareness naturally gives rise to unease, sorrow, or moral urgency. The boundary between personal fortune and collective suffering becomes blurred through insight into interdependence and non-self, rendering the well-being of others integral to one’s own liberation.

This view is especially emphasized in Mahāyāna Buddhism, where the path of the bodhisattva is marked by the deliberate postponement of one’s own final liberation until all sentient beings are freed from suffering. This idea stands in contrast to certain interpretations of individual liberation in Theravāda contexts, where personal nibbāna is a legitimate and central goal (arahant-ship). Genuine liberation entails a deeply internalized, empathetic concern for others’ wellbeing — a spontaneous motivation to alleviate their suffering grounded in insight, not obligation.

This perspective is rooted in the recognition that suffering is a shared existential condition, and that personal liberation remains incomplete while others continue to suffer. As the practitioner’s insight into the absence of a fixed, autonomous self (anattā) deepens, the perceived boundary between self and other begins to dissolve. The pain of others is no longer regarded as external but is experienced as one’s own. Compassionate action thus arises not as a prescribed rule but as the natural expression of wisdom and interdependence.

Such action is not reducible to altruism in the conventional sense, but reflects a non-dual understanding: the illusion of a distinct and separate self dissolves, and the suffering of others becomes intimately inseparable from one’s own. Ethical conduct, in this light, emerges not from obligation but from the spontaneous unfolding of insight into the interconnected nature of existence. As expressed in foundational Mahāyāna texts such as the Śikṣāsamuccaya and the Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa Sūtra, this interconnectedness (pratītyasamutpāda) implies that no being can truly be free while others remain trapped in dukkha. Compassionate action is therefore not optional, but intrinsic to awakened understanding.

The role of intention and mindfulness

A distinguishing feature of Buddhist ethics is its strong emphasis on intention (cetanā). Moral valuation depends heavily on the quality of the volition behind the act rather than on outcomes alone. In Buddhist thought, volition is considered the essential seed of karma: “It is volition, monks, that I call karma; for having willed, one acts by body, speech, and mind” (AN 6.63). An action done out of malice or greed, even if it has beneficial consequences, is not ethically commendable. Conversely, a mistake arising from wholesome intentions is evaluated more leniently.

Mindfulness (sati) plays a crucial role in this ethical dynamic. It is not mere attention but a lucid awareness of one’s inner states and external conditions. Mindfulness enables the practitioner to recognize unwholesome impulses, such as anger, envy, or attachment, at the moment of their arising, thus creating the possibility of conscious ethical choice. Without mindfulness, one is easily swept away by habitual patterns rooted in craving and ignorance.

The cultivation of mindfulness strengthens the capacity to regulate and purify intentions. In turn, the continuous refinement of intention deepens mindfulness. Together, they form a dynamic loop of ethical development, supporting the gradual transformation of character envisaged in the broader Buddhist path. Ethical behavior thus becomes not a rigid adherence to rules, but the natural outcome of an aware and selfless mind responding appropriately to the conditions of each moment.

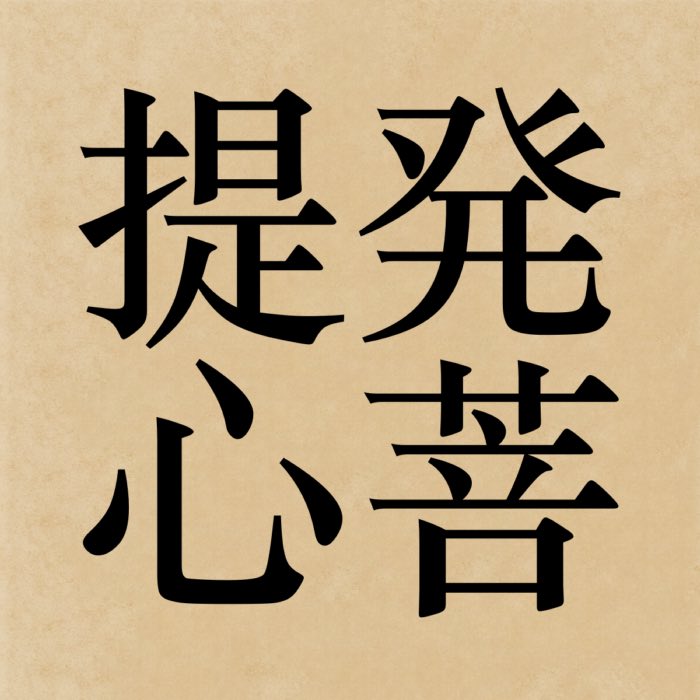

The Four Bodhisattva Vows in Mahāyāna Buddhism

As the practitioner’s ethical character matures, Buddhist traditions, particularly in Mahāyāna, articulate this commitment through profound, lifelong vows aimed at the liberation of all beings. A central ethical and spiritual commitment in Mahāyāna Buddhism is encapsulated in the Four Bodhisattva Vows, which express the aspiration to dedicate one’s life to the liberation of all sentient beings. These vows are not merely aspirational but serve as guiding ethical principles that shape the Mahāyāna path at its core:

- Sentient beings are numberless; I vow to liberate them all.

- Delusions are inexhaustible; I vow to extinguish them all.

- Dharma gates are boundless; I vow to enter them all.

- The path of awakening is unsurpassable; I vow to realize it.

These vows reflect a profound ethical ideal in which personal liberation is integrated with an open-ended and compassionate engagement with the world. They express both the infinite scope of the Mahāyāna vision and the resolve of the bodhisattva to confront suffering with limitless patience, wisdom, and determination. Although it is acknowledged that the vows describe goals that may never be fully completed, their significance lies in the enduring commitment they foster: the vows are renewed continuously, serving as ethical orientation points throughout one’s life and practice.

In this way, the Bodhisattva Vows do not prescribe specific behaviors but cultivate an existential attitude grounded in universal compassion (karuṇā) and wisdom (prajñā), aligning personal transformation with the liberation of all beings.

The Six Pāramitās (perfections)

Closely linked to the Bodhisattva Vows in Mahāyāna Buddhism are the Six Pāramitās (Sanskrit, Pāli: Pāramī, “other shore” in the sense of ‘transcendence’, “perfection”), which articulate the core ethical and spiritual qualities a bodhisattva cultivates on the path to full awakening. These are not isolated virtues but mutually reinforcing practices that combine ethical discipline, mental training, and insight.

- Generosity (dāna) – The practice of giving, materially or spiritually, without expectation of return. This includes not only offering goods and services but also sharing knowledge and protection.

- Ethical conduct (śīla) – Living in accordance with moral discipline, restraint, and integrity. This paramitā underpins all others by ensuring one’s actions do not cause harm.

- Patience (kṣānti) – The capacity to endure hardship, criticism, and provocation without anger or resentment. It reflects a deep emotional stability rooted in insight.

- Diligence (vīrya) – Energetic perseverance and enthusiasm in pursuing wholesome actions and avoiding unwholesome ones. It sustains long-term commitment to the bodhisattva path.

- Meditative concentration (dhyāna) – The cultivation of a focused and tranquil mind through meditative practice. This fosters clarity, calm, and the capacity for deep insight.

- Wisdom (prajñā) – The understanding of reality as it truly is, particularly the insights into impermanence (anicca), non-self (anattā), and interdependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda).

These perfections serve as both practical guidelines and aspirational ideals, progressively refining the Bodhisattva’s ability to act for the benefit of all beings. Importantly, they are not to be interpreted as sequential steps, but as qualities to be cultivated simultaneously and repeatedly throughout one’s ethical and spiritual development.

The Theravāda tradition, while not focused on the Bodhisattva ideal, also recognizes a series of perfections known as the Ten Pāramī. Five of these overlap with those in the Mahāyāna tradition. The Ten Pāramī are:

- Dāna Pāramī – Bearing-mindedness, liberality

- Sīla Pāramī – Ethical behavior, morality

- Nekkhamma Pāramī – Voluntary renunciation, renunciation

- Pajjā Pāramī – wisdom

- Viriya Pāramī – Willpower, energy

- Khanti Pāramī – Patience

- Sacca Pāramī – Truthfulness

- Adhiṭṭhāna Pāramī – Stamina, determination

- Metta Pāramī – Compassionate kindness, loving kindness

- Upekkhā Pāramī – Equanimity

Like the Mahāyāna perfections, they serve not only as ethical guidelines but also as tools for deep psychological and spiritual transformation.

The ten non-virtues and their opposites in karmic ethics

In addition to aspirational frameworks like the Six Pāramitās, Buddhist traditions also offer practical ethical guidelines based on avoiding unwholesome actions and cultivating their wholesome counterparts. A key feature of this ethical framework, particularly emphasized in Tibetan traditions but present across all schools, is the framework of the ten non-virtuous actions (akusala-kamma) and their corresponding virtuous opposites. This framework provides a concrete and psychologically nuanced approach to morality, focusing on intentionality and karmic consequences.

The ten unwholesome actions are divided into three categories — of body, speech, and mind — each contributing to the moral texture of a person’s life and future rebirths. Their opposites are not merely the absence of wrongdoing, but active qualities to be cultivated.

Body

- Killing → Abstaining from taking life; fostering protection and reverence for living beings

- Stealing → Respecting others’ property; practicing generosity and honesty

- Sexual misconduct → Engaging in respectful, consensual conduct; upholding personal and relational integrity

Speech

- Lying → Speaking truthfully and sincerely

- Divisive speech → Creating harmony; avoiding gossip or sowing discord

- Harsh speech → Using kind, gentle, and respectful language

- Idle chatter → Speaking meaningfully and purposefully

Mind

- Covetousness → Rejoicing in others’ good fortune and success

- Ill-will or malice → Cultivating goodwill, patience, and compassion

- Wrong views → Developing right understanding, especially concerning karma, ethical causality, and the path to liberation

This model does not serve merely as a checklist of moral dos and don’ts. Rather, it reflects the Buddhist view that actions arise from mental states and that ethical transformation requires attention to the roots of behavior — particularly greed (lobha), hatred (dosa), and delusion (moha). Practicing the opposites of these ten unwholesome actions gradually purifies these mental afflictions, aligning one’s intentions with the broader aim of reducing suffering for oneself and others.

A contemporary synthesis of Buddhist ethical commitments

The following is a personal compilation of vows and ethical precepts (śīlas), inspired by various Buddhist traditions and texts, which I have gathered and synthesized over the past years. These include the Five Precepts (pañca śīla), the Bodhisattva Vows of Mahāyāna Buddhism, the six pāramitās, the Ten Non-Virtues and their opposites as found in karmic ethics, the Forty-Eight Bodhisattva Precepts from the Brahmajāla Sūtra, the Four Immeasurables (brahmavihāras), and the principles of Engaged Buddhism. While no single text contains all of these commitments in this exact form, they together represent a synthesis of Buddhist moral and ethical teachings across diverse traditions. Alongside the Five Precepts, they support the daily cultivation of compassion and wisdom (prajñā) for the benefit of oneself and all sentient beings, and form the basis of the bodhicitta aspiration:

- Not to harm or kill any sentient being.

- To strive to alleviate the physical suffering of others.

- To relieve the emotional suffering of others.

- Not to take what has not been freely given.

- To handle what one receives with care and respect.

- Not to accept anything known to have been stolen.

- Not to engage in sexual relations without love, and to respect both others’ relationships and one’s own.

- Not to use words to harm or injure.

- Not to speak untruths.

- To allow others to express themselves and to listen attentively.

- To show respect toward elders.

- To care for the sick and vulnerable.

- To respond to questions one is capable of answering.

- To offer assistance when it is genuinely needed.

- To accept help when it is sincerely offered.

- Not to expect gratitude in return for giving.

- To share possessions with those in need, when asked appropriately and without attachment.

- Not to refuse a gift and to appreciate every offering.

- Not to accept an invitation for the following reasons:

- Out of anger, with the intent to harm another

- Out of pride, believing oneself too superior to associate with those of lower status

- Out of jealousy, fearing disapproval from others of higher status

- Not to respond to insults with insults, to scolding with scolding, to anger with anger, to violence with violence, or to criticism with retaliation.

- Not to act on feelings of anger or allow them to dominate one’s mind.

- To uphold aesthetic and ethical principles that promote well-being for oneself and others.

- Not to damage or leave a place in a state unfit, harmful, or inhospitable for other living beings.

- To act in accordance with the inclinations of others, where appropriate and compassionate.

- To speak in praise of others’ talents and virtues.

- To prevent harmful actions, especially by those who pose a threat to the Dharma, using skillful and appropriate means.

- Not to speak ill of any sentient being.

- Not to praise oneself or criticize others out of desire, greed, jealousy, a need for recognition, or a craving for affection — regardless of whether what is said is true or false, or of the social status involved. Even entertaining such thoughts for these reasons is to be regarded as blameworthy.

- Not to create discord or confusion among others.

- Not to lead others away from their convictions or their chosen path.

- To listen and empathize when others apologize, rather than ignoring, dismissing, or despising them; and not to follow angry thoughts with acts of harm.

- Not to despise or reject others, nor to see them as inferior, merely because they do not share one’s beliefs.

- Not to denigrate or declare invalid any views that one no longer holds or has never held; rather, to recognize the potential value such views may hold for personal insight.

- Not to hold views that contradict the Dharma, especially the Four Immeasurables. This includes neither denying what is true and valuable, nor expressing hostility toward these teachings or those who uphold them.

- Not to falsely claim realization of the profound nature of emptiness.

- Not to teach the concept of emptiness to those not yet ready to understand it.

- Not to withhold the Dharma due to misguided notions of spiritual stinginess when it is sincerely and appropriately requested.

- Not to lead others into one’s own misconceptions, nor to disparage alternative paths of realization by claiming that they do not lead to liberation. Many paths may differ in method, yet share a common foundation and goal.

- Not to dissuade others from striving for complete enlightenment, nor to encourage them to seek only their own release from suffering.

- Not to encourage abandonment of moral vows or ethical commitments once taken.

- To care for the needs of those under one’s guidance.

- Not to create unjust conditions by redirecting resources away from those practicing concentration due to bias or hostility, and favoring those merely reciting texts.

- To earnestly cultivate the Four Immeasurables: loving-kindness (mettā), compassion (karuṇā), sympathetic joy (muditā), and equanimity (upekkhā).

- Not to neglect the daily practice of mindfulness.

- Not to neglect care for the body.

- Not to neglect care for the mind.

- Not to seek out distractions when time could be used for Dharma practice.

- Not to indulge in idle or meaningless chatter.

- Not to judge others based solely on hearsay or public opinion. One easily forms absolute judgments from a distance, but true understanding requires openness and the possibility of offering unconditional compassion.

- Not to give in to the grasping and desirous tendencies of the mind.

- Not to cloud the mind with intoxicants — whether substances, words, actions, or thoughts.

- Not to devalue one’s individuality in comparison to others, nor to abandon it out of self-negation or spiritual euphoria.

These vows should not be understood as a rigid or exclusionary set of rules. They are not intended to limit modes of insight, nor do they imply that simply following them guarantees realization. As ethical commitments (śīlas), they function as guides — an attitude toward life oriented toward restraint from harmful behaviors. Maintaining them requires mindfulness, vigilance, and self-discipline, all of which form part of the daily practice of mindfulness (sati), right livelihood, right speech, and right action within the Noble Eightfold Path.

Addressing the breach of vows in Buddhist contexts

From a Buddhist perspective, the breach of ethical precepts is not handled through punishment or concepts of sin but through a process of ethical reflection and restorative practice:

- Regret – Distinct from guilt, regret is the wish that one had not committed a certain action, without attaching it to self-condemnation. While guilt may lead to psychological stagnation, regret is viewed as a constructive attitude that opens the way to ethical renewal.

- Resolution – One reaffirms the intention not to repeat the harmful behavior, even if this intention was already present during the breach.

- Reorientation – This involves consciously returning to one’s ethical foundation and rededicating one’s life to the goals of mental clarity and universal benefit.

- Compensatory action – Actions such as meditation on compassion, acts of generosity, or apologies are considered effective means to counteract the karmic impact of transgressions. These serve to re-establish self-respect and mindful accountability.

This approach differs notably from many Western ethical systems, particularly those shaped by Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) or Enlightenment rationalism. In Western contexts, moral transgressions are often interpreted through frameworks of guilt, punishment, or sin — typically anchored in divine law, legalistic norms, or social contracts. Buddhism, by contrast, approaches ethical failure as part of a process of ongoing mental cultivation. Instead of viewing the transgressor as inherently flawed or morally corrupt, Buddhist ethics emphasizes volitional clarity, contextual analysis, and the possibility of ethical rehabilitation through conscious effort. This orientation supports a dynamic and individualized response to moral failure, one that integrates psychological insight with practical re-alignment.

Conclusion

Buddhist ethics, as developed across its various traditions, emerges as a comprehensive model of moral and psychological transformation. It is grounded in intentionality (cetanā), mindful awareness (sati), virtue cultivation, and the pragmatic aim of reducing suffering (dukkha). Unlike many Western ethical systems that prioritize obedience to external rules, social contracts, or divine commandments, Buddhist ethics emphasizes internal transformation, character development, and insight into the impermanent and interdependent nature of existence.

Rather than focusing on rigid prescriptions, Buddhist ethics fosters the gradual formation of an awakened character: a selfless disposition that naturally expresses compassion (karuṇā), sympathetic joy (muditā), loving-kindness (mettā), and equanimity (upekkhā). Ethical conduct is not separated from cognitive and existential insight but arises as its natural unfolding. Particularly in Mahāyāna contexts, the aspiration to liberate all sentient beings, as expressed in the Bodhisattva Vows and cultivated through the Six Pāramitās, demonstrates how moral responsibility expands beyond the self, rooted in the recognition of shared suffering and the dissolution of self/other boundaries.

At the heart of this model lies the understanding that ethical transformation is a long-term, embodied practice. The Noble Eightfold Path (Ariyo Aṭṭhaṅgiko Maggo) serves as both the structural foundation and the developmental process guiding this transformation, linking ethical conduct (sīla), mental discipline (samādhi), and wisdom (paññā) into a single, integrated path. Far from being reducible to altruism, Buddhist ethics presents an existential vision in which genuine freedom and ethical responsiveness arise from the same realization of non-self (anattā) and dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda).

Whereas Western ethical thought has historically emphasized justice, obligation, or rational autonomy, Buddhist ethics anchors morality in mental purification, volitional clarity, and universal empathy. By dissolving the self/other dichotomy, it shifts moral responsibility from external enforcement to the spontaneous compassion of an awakened mind. In an age increasingly marked by pluralism, global interconnection, and ethical uncertainty, the Buddhist approach, with its emphasis on self-cultivation, interdependence, and the transformation of intention, offers, in my view, a particularly promising framework for meaningful global ethical dialogue.

References and further readings

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments