Amitābha Buddha: The Buddha of infinite light

Amitābha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, is one of the most revered figures in Mahāyāna Buddhism, embodying boundless compassion and wisdom. As the presiding Buddha of the Pure Land of Sukhāvatī, Amitābha offers a path to liberation that is accessible to all beings through faith, aspiration, and devotion. In this post, we explore the origins, symbolism, and practices associated with Amitābha, highlighting his profound role in Buddhist soteriology and his relevance across cultures and traditions.

Standing Amida with light rays (48 in number, symbolizing his past vows), haloes and welcoming mudra, Japan, today: Museo d’arte orientale, Turin, Italy. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Introduction

Amitābha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, holds a central place in the devotional and philosophical imagination of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Revered as a cosmic Buddha who presides over the western Pure Land of Sukhāvatī, he embodies the boundless compassion and wisdom of awakened consciousness made accessible to all beings. Unlike the historical Buddha Siddhartha Gautama, Amitābha represents a transcendent and timeless dimension of Buddhahood, whose salvific power is mediated through faith, aspiration, and devotional practice.

His significance is most clearly articulated in the Pure Land traditions, which developed from Indian Mahāyāna sources and took on distinct forms as they spread through Central and East Asia. In India, early Mahāyāna sūtras presented Amitābha as a Buddha who, in a previous life as the Bodhisattva Dharmākara, made a series of vows to establish a realm free from obstacles to spiritual practice. These vows became the foundation for a system of soteriology centered not on monastic discipline or meditative achievement alone, but on the possibility of rebirth in a Buddha-field conducive to enlightenment.

As Pure Land thought evolved in China, Japan, and Tibet, Amitābha came to embody a highly inclusive vision of liberation. His vow to receive all who sincerely call upon his name created a path accessible even to those lacking the time, ability, or conditions to engage in advanced spiritual training. For many lay practitioners, Amitābha became not just a symbol of transcendence, but an intimate figure of refuge — a Buddha who listens, welcomes, and redeems.

This dual identity, as both a cosmic principle and a personal savior, makes Amitābha unique within the Buddhist pantheon. He bridges the abstract ideals of Mahāyāna metaphysics with the emotional immediacy of popular devotion, offering a vision of awakening that is both universally compassionate and pragmatically accessible.

Pure Land

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, a Pure Land (Sanskrit: buddhakṣetra) refers to a purified realm established by the merit, vows, and enlightened activity of a Buddha or advanced Bodhisattva. Unlike ordinary realms within saṃsāra, which are shaped by karmic impurities and afflictive emotions, Pure Lands are free from defilements and structured to support spiritual development. In these realms, the Dharma is readily available, and beings can progress toward awakening without the typical hindrances of suffering, ignorance, or moral confusion.

Each Pure Land reflects the particular vows and qualities of its presiding Buddha. While Sukhāvatī, the western Pure Land of Amitābha, is the most widely venerated, others include Abhirati (the eastern Pure Land of Akṣobhya) and Vaiḍūryanirbhāsa (the realm of Bhaiṣajyaguru, the Medicine Buddha). Whether understood cosmologically or metaphorically, Pure Lands represent idealized fields of practice that embody the compassionate responsiveness of awakened beings.

Scriptural foundations and historical origins

The core scriptural basis for Amitābha Buddha and his Pure Land is found in three principal Mahāyāna texts: the Shorter Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, the Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, and the Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra. Together, these form the textual foundation of the Pure Land tradition and present Amitābha as both a savior figure and a cosmic embodiment of enlightened compassion.

The Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra is especially significant, as it narrates the story of Dharmākara Bodhisattva, a former king who, inspired by the teachings of the Buddha Lokeśvararāja, renounced his throne to pursue enlightenment for the benefit of all beings. He made 48 vows, outlining the conditions for his future Buddha-field, Sukhāvatī, with the most important being the 18th vow. In it, he promises that any being who sincerely aspires to be reborn in his Pure Land and calls upon his name will be guaranteed entry — unless they are insincere or not yet spiritually committed. This emphasis on universal accessibility, faith, and aspiration became the doctrinal core of Pure Land belief.

The Shorter Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra provides a concise but vivid description of the splendor of Sukhāvatī, portraying it as a land free of suffering, where beings can hear the Dharma constantly and attain enlightenment with ease. The Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra, more meditative in character, teaches sixteen contemplations focused on Amitābha and his Pure Land. It became especially influential in Chinese and Japanese traditions as a guide for visualizing Amitābha at the time of death.

Historically, Pure Land ideas began to emerge within Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism between the 1st and 4th centuries CE, growing alongside other forms of devotional and cosmological thought. These texts likely developed in North India and Central Asia, in response to a growing emphasis on universal salvation and the recognition that most beings lacked the capacity for arduous meditative or monastic discipline. The vision of a Buddha-field open to ordinary practitioners provided a powerful alternative and complemented the Bodhisattva ideal of inclusive liberation. From these Indian origins, the Pure Land sūtras spread along the Silk Road and were later translated into Chinese, catalyzing new schools of Buddhist practice focused on Amitābha and the Pure Land as the soteriological goal.

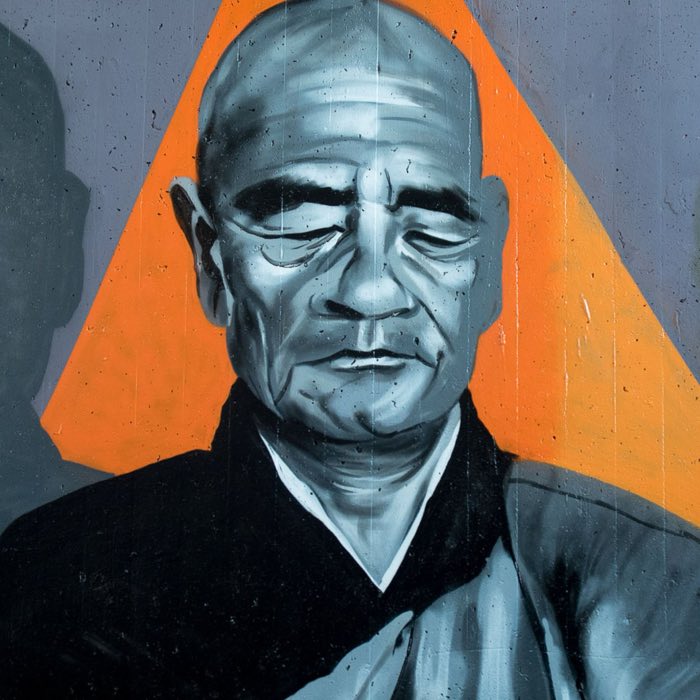

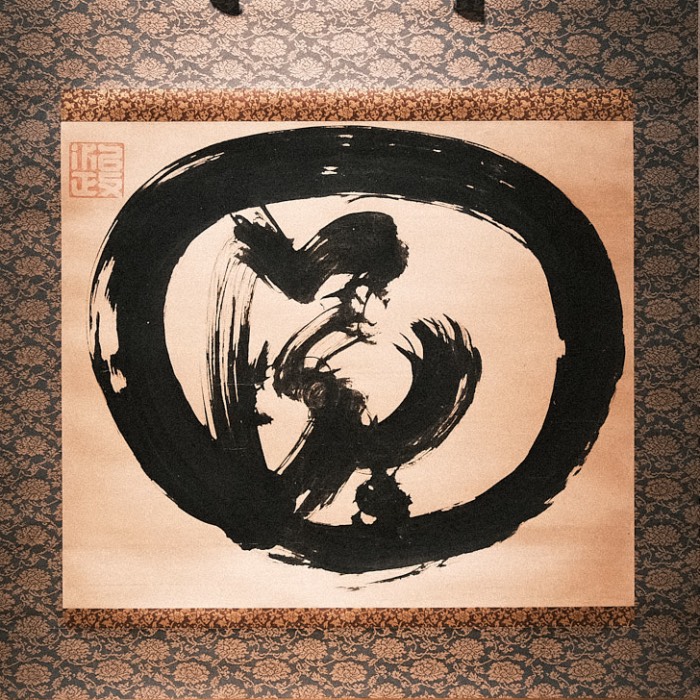

Symbolism and iconography

The symbolism and iconography associated with Amitābha are rich and layered, reflecting his role as a transcendent Buddha whose presence illuminates the path to liberation. His name, “Amitābha”, means “Infinite Light”, while the variant “Amitāyus” translates as “Infinite Life”. These two aspects highlight the dual symbolic significance of his nature: he is a source of both boundless spiritual illumination and limitless longevity. In Japanese traditions, he is also known as Amida, a name that similarly emphasizes his immeasurable qualities.

Amitābha is typically depicted in serene, meditative postures. He is most often shown seated in the lotus position, resting atop a lotus throne that signifies purity and spiritual emergence from the mire of samsāra. His hands form specific mudrās depending on context. In many East Asian depictions, he is seen performing the gesture of welcome (varada mudrā) with one or both hands lowered and open, symbolizing his readiness to receive beings into his Pure Land. In the context of the Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra, he may also appear with a vessel of nectar, representing the elixir of immortality and the nourishment of Dharma.

The dominant color associated with Amitābha is red, representing compassion, vitality, and the transformation of desire into discriminating wisdom. As a member of the Five Tathāgatas in tantric systems, he is associated with the western direction, the skandha of perception (samjñā), and the fire element. These associations tie him not only to devotional practice but to meditative cosmology and inner psychological transformation.

Light is perhaps the most pervasive motif in Amitābha’s symbolism. His Pure Land, Sukhāvatī, is described as a realm suffused with radiant brilliance, where Amitābha’s light reaches all corners of the cosmos, dispelling ignorance and illuminating the minds of beings. This imagery reinforces his role as a beacon of clarity and refuge in an often dark and chaotic world.

Taken together, Amitābha’s iconographic features do more than represent theological ideas: they function as visual meditations on the qualities of Buddhahood — serenity, receptivity, clarity, and all-embracing compassion. For the devotee, encountering an image of Amitābha is not simply an act of veneration, but an invitation to recognize and awaken these same luminous capacities within themselves.

The Pure Land (Sukhāvatī)

Sukhāvatī, the Pure Land over which Amitābha presides, occupies a unique place in Buddhist cosmology and soteriology. It is described in the Pure Land sūtras as a realm of extraordinary purity, beauty, and spiritual opportunity — an idealized world created by the merit and vows of Amitābha to support beings on their path to enlightenment. In contrast to the suffering and distractions of ordinary realms within saṃsāra, Sukhāvatī is envisioned as a realm devoid of pain, defilements, or obstacles to Dharma practice.

The sūtras portray Sukhāvatī as replete with shimmering lotus ponds, jewel-encrusted trees, melodious birds that recite the Dharma, and beings who are spontaneously born in lotus flowers rather than through karmically conditioned birth. These elements are not intended merely to dazzle the imagination but serve as didactic tools to emphasize the spiritual advantages of rebirth in such a place. In Sukhāvatī, beings hear the Dharma constantly, live without fear or distraction, and can swiftly progress toward Buddhahood under Amitābha’s guidance.

When compared to other Buddhist cosmologies, such as the multiple heavens and hells or the six realms of rebirth, Sukhāvatī functions as a distinct category of Buddha-field (Sanskrit: buddhakṣetra). Unlike the celestial realms associated with karmic reward and eventual decline, the Pure Land is designed specifically for spiritual acceleration. It is neither a temporary pleasure realm nor a final resting place but a strategic locus for practice leading to liberation. In this way, Sukhāvatī complements rather than replaces the traditional cosmological structure, offering a purified and idealized context for fulfilling the Bodhisattva vow.

Philosophical interpretations of Sukhāvatī vary across Buddhist traditions. Some lineages take the Pure Land as a literal realm that one is reborn into through faith and practice, while others interpret it metaphorically — as a symbolic representation of inner purity, the transformation of mind, or even the manifestation of non-dual awareness. In Chán and Zen Buddhism, for instance, Sukhāvatī is sometimes seen as a state of awakened mind rather than a geographical location. These divergent readings reflect broader debates within Mahāyāna about the role of faith, metaphor, and ontological realism in soteriology.

Despite these differences, the concept of Sukhāvatī retains its central function across traditions: it is a vision of the world purified by compassion and wisdom, offering hope to practitioners who may feel overwhelmed by the complexities of ordinary existence. Whether taken literally or metaphorically, the Pure Land continues to serve as a powerful symbol of accessible liberation and the compassionate reach of Amitābha’s vow.

Devotional practice and faith (śraddhā)

Central to the Pure Land tradition is the practice of invoking Amitābha’s name, a devotional act rooted in faith (śraddhā), gratitude, and aspiration. This recitation, known as the nembutsu in Japanese or nianfo in Chinese, typically takes the form “Namo Amitābhāya” in Sanskrit or “Namu Amida Butsu” in [Japanese](/weekend_stories/told/2024/2024-12-27-japanese_language_and_writing_system/. While simple in appearance, this practice carries deep soteriological significance. It is believed that sincere recitation of Amitābha’s name, grounded in trust and the desire for rebirth in the Pure Land, establishes a karmic link with the Buddha and fulfills the conditions of his 18th vow.

Faith in this context is not blind belief but a form of existential trust: an openness to the liberating power of the Buddha’s vow and a willingness to entrust one’s awakening to that compassionate force. The devotional recitation is often accompanied by mental visualization, ethical conduct, and an aspiration to be reborn in Sukhāvatī, where the conditions for practice are ideal. For many practitioners, particularly those unable to undertake rigorous meditation or monastic discipline, this path provides a practical and emotionally resonant method to engage the Dharma.

In China, this practice developed into a major religious movement, forming the basis of Pure Land schools such as those led by Tanluan, Daochuo, and Shandao. These teachers emphasized the power of Amitābha’s vow over the practitioner’s own efforts, thus centering salvation on Amitābha’s grace. Nianfo chanting became a widespread practice among monks and laypeople alike, often performed in communal settings, sometimes at the hour of death to facilitate a favorable rebirth.

In Japan, Pure Land thought reached new prominence with the development of the Jōdo and Jōdo Shinshū schools. The Jōdo tradition, founded by Hōnen, advocated exclusive reliance on the nembutsu, making it the sole practice necessary for rebirth. His disciple Shinran further radicalized this stance, asserting that even a single, sincerely uttered nembutsu, grounded in true entrusting faith (shinjin), was sufficient. For Shinran, human effort (jiriki) was inherently limited, and only the power of Amitābha (tariki) could ensure liberation. A view that redefined the relationship between self, practice, and grace.

Tibetan Buddhism, while typically more oriented toward tantric practices, also incorporates Amitābha devotion, particularly in contexts related to death and the intermediate state (bardo). Amitābha is often invoked during funerary rites, and visualizations of his Pure Land appear in certain terma texts and sādhanās. The Tibetan aspiration prayer to be reborn in Sukhāvatī reflects the pan-Mahāyāna appeal of Amitābha devotion.

Overall, the devotional practices associated with Amitābha illustrate a unique form of Buddhist engagement, where faith and repetition replace elaborate ritual or meditative mastery. They demonstrate a powerful democratization of the path, affirming that awakening is not restricted to elites but is accessible to all who sincerely call upon the Buddha of Infinite Light.

Soteriological role and philosophical debates

One of the most distinctive aspects of Pure Land thought is its emphasis on the role of “other-power” (tariki) as contrasted with “self-power” (jiriki). While traditional Mahāyāna practice often centers on meditative cultivation, ethical discipline, and intellectual understanding, i.e., paths that require significant individual effort, Pure Land Buddhism proposes a radically accessible alternative. It holds that the compassionate vows of Amitābha can support and even guarantee liberation for beings who entrust themselves to his power.

This dichotomy between self-power and other-power is not framed as a rejection of personal effort, but as a recognition of its limits in the face of karmic conditioning, spiritual fatigue, or existential despair. Especially in Jōdo Shinshū Buddhism, as articulated by Shinran, human beings are seen as mired in delusion and incapable of perfecting themselves through will alone. Therefore, entrusting oneself to Amitābha’s vow, and relying on his merit rather than one’s own, becomes the most viable soteriological strategy in the degenerate age (mappō).

This perspective raises important philosophical and doctrinal questions. Critics from within other Mahāyāna schools, including parts of the Chán and Zen traditions, have questioned whether reliance on other-power undermines the principle of direct insight into one’s own mind. For these schools, the idea of salvation through an external Buddha might seem to contradict the fundamental teaching that awakening arises from within. Some Chán critiques have argued that Pure Land reliance risks passivity or fatalism.

Defenders of the Pure Land path, however, have offered a robust response. They argue that other-power is not a form of dependency but an expression of interdependence, the insight that even spiritual progress is conditioned and that liberation cannot be fully separated from the relational fabric of existence. Amitābha’s vow is seen not as a supernatural shortcut but as a manifestation of the Bodhisattva ideal itself: the compassionate vow to make awakening accessible to all, especially the most burdened.

Furthermore, some thinkers have emphasized that the nembutsu itself is both an act of other-power and a practice of mindfulness, keeping the practitioner connected to the Dharma and the aspiration for awakening. Thus, the tension between self-effort and grace is not binary but dynamic, inviting a nuanced exploration of agency, humility, and spiritual trust.

In this light, the soteriological role of Amitābha is both profound and controversial. He challenges assumptions about spiritual elitism and opens a door for all beings, regardless of capacity or circumstance, to enter the path. Rather than abandoning the ideal of personal transformation, Pure Land thought redefines it through a radical reorientation toward faith, relationality, and the compassionate power of vow.

Amitābha in comparative context

Amitābha’s role within the Mahāyāna tradition extends beyond his centrality in Pure Land doctrine. He forms part of a triad alongside Avalokiteśvara (Guanyin/Kannon) and Mahāsthāmaprāpta (Daishizhi), who represent compassion and wisdom respectively. While Amitābha embodies infinite light and the salvific force of awakened vow, Avalokiteśvara and Mahāsthāmaprāpta serve as his principal attendants, assisting in the reception of beings into the Pure Land. This triadic structure reinforces a holistic soteriological vision wherein the emotional, intellectual, and spiritual faculties are harmonized.

Amitābha’s influence can also be traced through a broad spectrum of East Asian cultural forms. In visual art, he appears in paintings, sculptures, and temple murals across China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Iconographically, he is often shown descending at the moment of death to receive the faithful into Sukhāvatī, flanked by Avalokiteśvara and Mahāsthāmaprāpta in the “welcoming descent” (raigō) motif. Such imagery serves not only devotional purposes but reinforces the idea of death as a spiritual opportunity rather than a final end.

In literature, Amitābha features in popular tales, miracle accounts, and poetic evocations of Sukhāvatī. His presence in chanting liturgies, deathbed rituals, and aspiration prayers reflects a deeply integrated devotional culture that spans elite monastic institutions and household practice. The invocation of his name offers a unifying thread across otherwise diverse communities, linking doctrinal abstraction with emotional immediacy.

Comparatively, Amitābha’s figure also serves as a symbol of universal accessibility to enlightenment. In contrast to Buddhas who may be seen as remote or transcendent, Amitābha is defined by his relational approach to suffering beings. His vows frame salvation not as a reward for effort but as a gift made possible by deep compassion and the recognition of human limitation. As such, Amitābha bridges the gap between high philosophical ideal and everyday spiritual life, making the Dharma truly available to all who seek refuge in its light.

Conclusion

Amitābha Buddha represents one of the most integrative and accessible expressions of Mahāyāna Buddhist thought. As a transcendent figure rooted in sūtra and devotional practice, he bridges the domain of philosophical metaphysics with the emotional and ethical immediacy of lived faith. His 48 vows, particularly the promise of rebirth in the Pure Land for all who sincerely invoke his name, offer a radically inclusive vision of salvation that contrasts with more effort-based paths within the Buddhist tradition.

The appeal of Amitābha lies in this responsiveness to the human condition. His vow does not exclude those who are untrained, impure, or incapable of advanced meditative practice; instead, it provides a framework in which spiritual liberation remains possible through trust, aspiration, and moral commitment. For many, particularly in East Asia, this opens the Buddhist path to ordinary people and affirms that awakening is not the privilege of the elite but the potential of every being.

The Pure Land itself, whether understood literally or symbolically, functions as a conceptual space in which the ethical and epistemic conditions for awakening are optimized. It reflects a compassionate recalibration of Buddhist soteriology, adapted to the needs and limitations of the world. In this sense, the figure of Amitābha not only offers comfort or inspiration but also transforms the structure of Buddhist practice by emphasizing relationality, interdependence, and the salvific power of vow.

In contemporary global Buddhism, Amitābha continues to serve as a powerful focal point for ritual, reflection, and moral orientation. Whether invoked in daily chanting, depicted in temple art, or contemplated in philosophical dialogue, he remains a symbol of the Dharma’s responsiveness to human fragility. As traditions continue to evolve, the model offered by Amitābha, one that affirms both the universal accessibility of awakening and the necessity of compassionate presence, retains deep relevance in a world shaped by both existential uncertainty and spiritual aspiration.

References and further reading

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments