Buddhism: A short introduction to its history and heart

Buddhism stands as one of the most influential religious and philosophical traditions in the world, shaping not only spiritual practice but also art, literature, and social institutions across Asia and beyond. From its roots in ancient India to its far-reaching expansions via trade routes and patronage by powerful rulers, Buddhism embodies a complex mosaic of ideas, historical developments, and cultural adaptations. In this post, we give a short introduction to Buddhism as a start of a new series on the history and philosophy of this tradition.

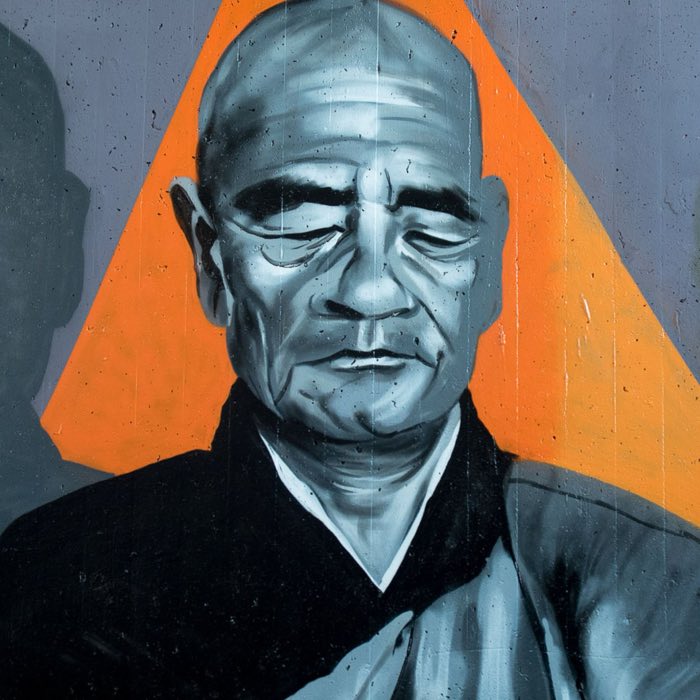

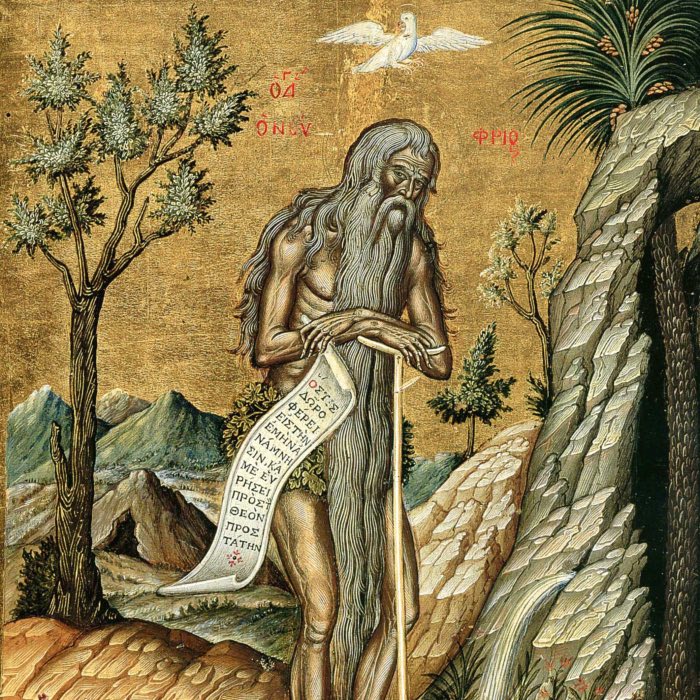

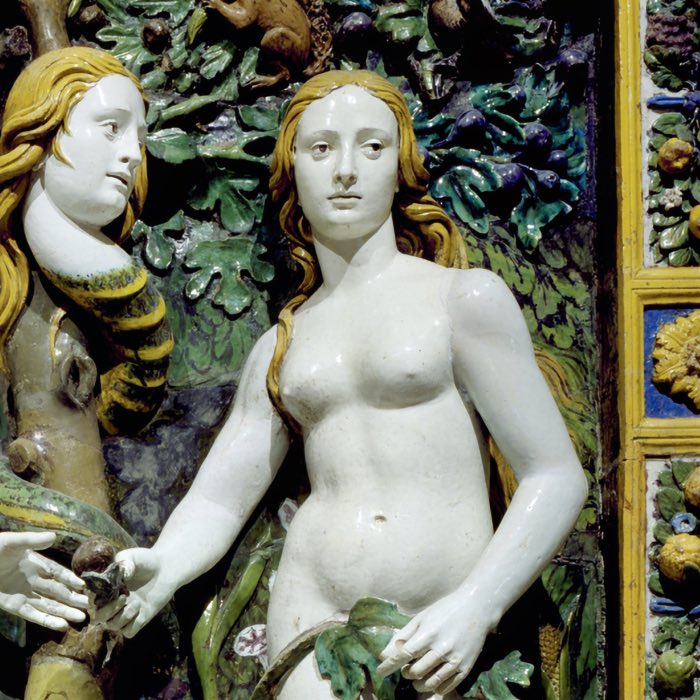

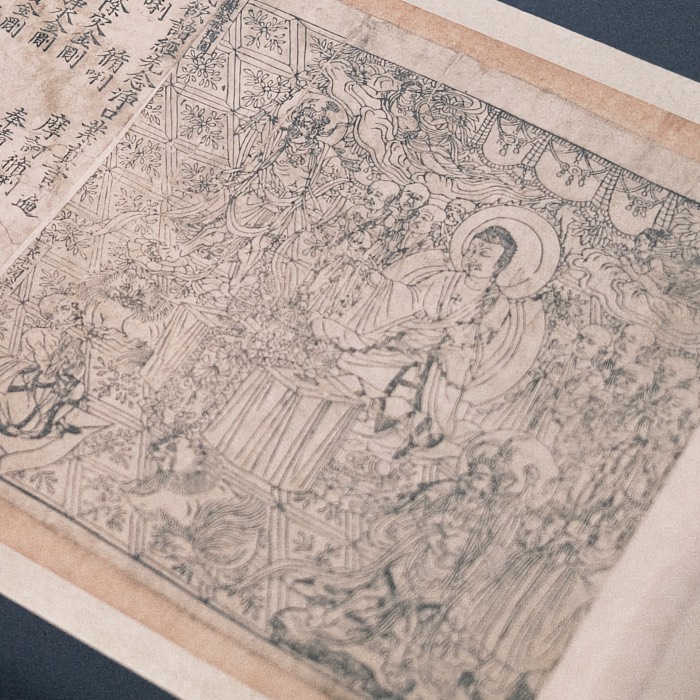

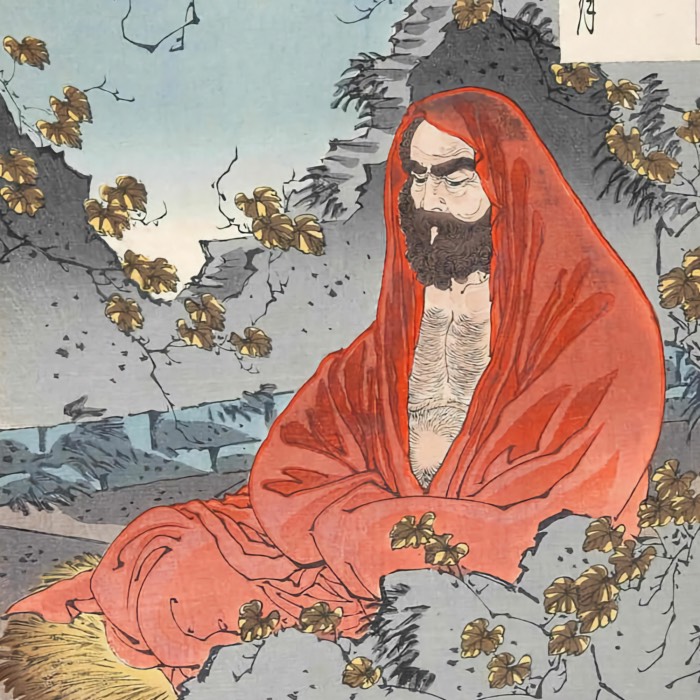

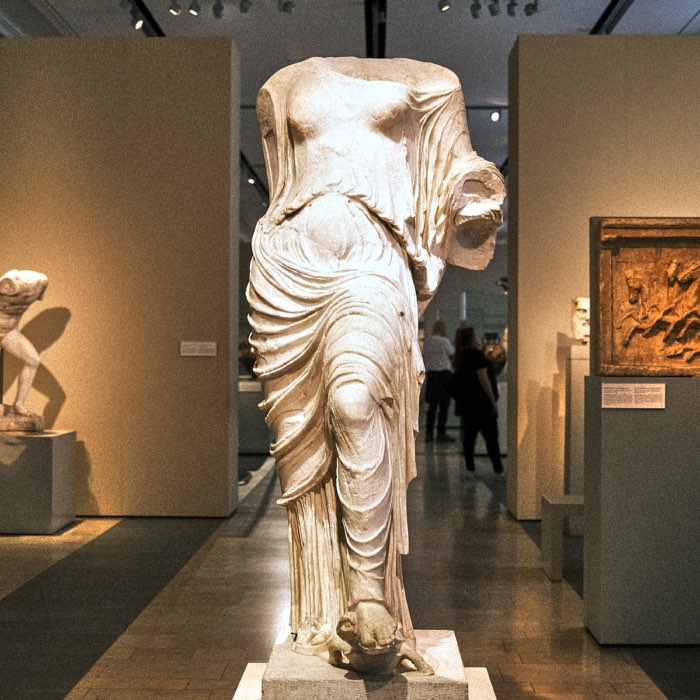

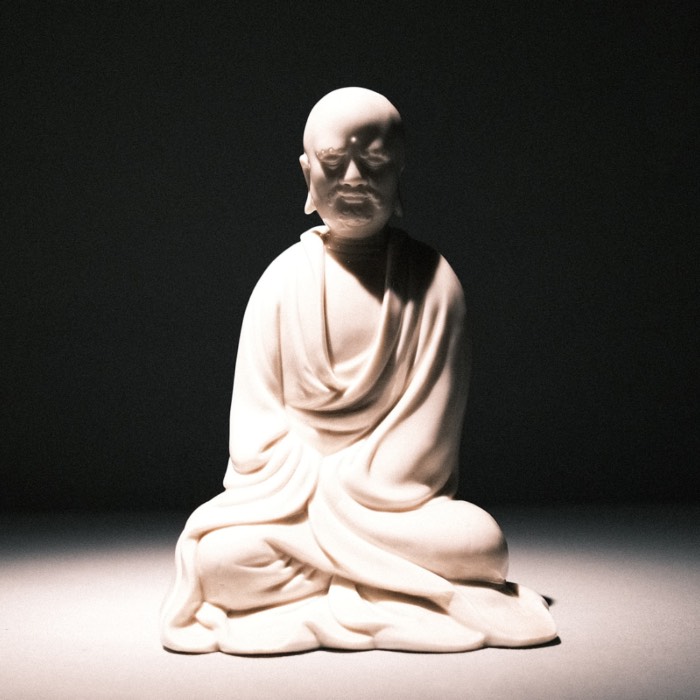

Torso of a Buddha statue, Northern Thailand, Lan Na Thai, c. 1500, bronze. The fragment belonged to an elegant seated Buddha figure whose right hand was probably pointing downwards in a gesture of touching the earth. The surface shows the jade-green patina typical of bronzes from northern Thailand. Siddhartha Gautama, stylized as the Buddha, is the most common motif in Buddhist art. Buddhism is a religion and philosophy that originated in ancient India and has since spread throughout Asia and beyond. This post is the first in a series of articles exploring the history and philosophy of Buddhism. The image was taken at the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in 2025.

Torso of a Buddha statue, Northern Thailand, Lan Na Thai, c. 1500, bronze. The fragment belonged to an elegant seated Buddha figure whose right hand was probably pointing downwards in a gesture of touching the earth. The surface shows the jade-green patina typical of bronzes from northern Thailand. Siddhartha Gautama, stylized as the Buddha, is the most common motif in Buddhist art. Buddhism is a religion and philosophy that originated in ancient India and has since spread throughout Asia and beyond. This post is the first in a series of articles exploring the history and philosophy of Buddhism. The image was taken at the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in 2025.

Core beliefs and worldview

Buddhism is not centered on worshiping a deity or adhering to a fixed set of dogmas but is best understood as a path of insight and liberation. It offers a profound examination of the human condition, recognizing suffering as an inherent part of existence and providing a means to transcend it through wisdom, ethical conduct, and mental discipline.

Central to Buddhism is the Dharma, a term that encompasses both the natural order of existence and the teachings that guide practitioners toward awakening. Unlike many religious traditions that place emphasis on divine intervention or obedience to sacred laws, Buddhism asserts that liberation is achieved through direct insight into reality. This is cultivated through practices that develop ethical awareness, meditative stability, and wisdom, qualities that dissolve ignorance and craving, which are seen as the root causes of suffering.

At its heart, Buddhism offers a radical reorientation of how we perceive existence: what we take as stable entities, including the self, are in fact fluid processes. The world is not made of things, but of events in constant flux, conditioned and interdependent.

Buddhism does not present a single, rigid doctrine but rather a dynamic tradition that has evolved over centuries. While it takes different forms in various cultural contexts, certain fundamental principles remain central across all Buddhist schools:

- Reality is characterized by impermanence and interdependence: Everything in existence is in a constant state of change, and all things arise through causes and conditions.

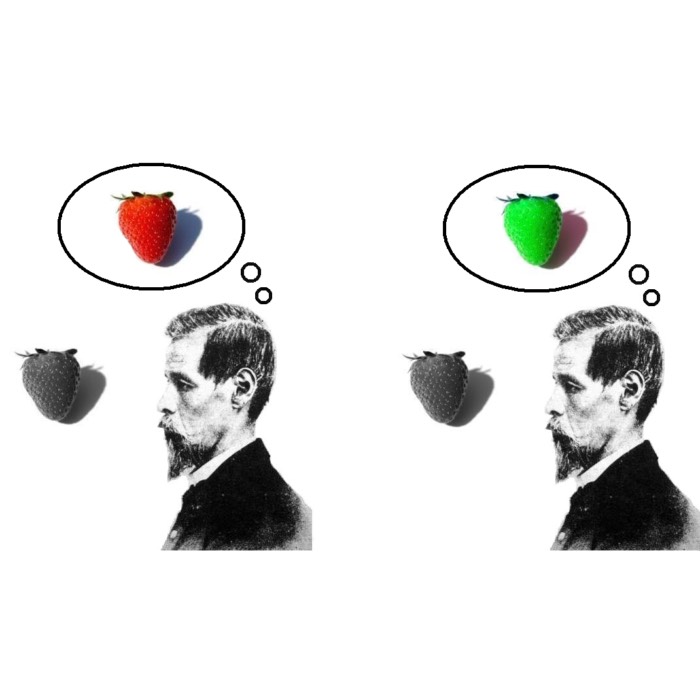

- There is no permanent, unchanging self: The sense of a fixed, independent identity is an illusion; all experiences arise from an interplay of constantly changing mental and physical processes. What we call a “self” is a conceptual label for a momentary configuration within this dynamic flow.

- Suffering arises from craving and ignorance: The cycle of dissatisfaction persists due to attachment and misperception, but it can be transcended through wisdom and disciplined practice.

- Liberation is possible: The path to awakening is accessible to anyone willing to cultivate ethical conduct, meditation, and insight.

Buddhism is not a belief system in the conventional sense but an experiential path, one that invites inquiry, reflection, and direct realization. It provides a practical framework for transformation, guiding individuals toward greater clarity, compassion, and freedom from suffering.

To further explore the diversity and depth of Buddhism, the following lists present key teachings, philosophical frameworks, and traditions that shape Buddhist thought and practice. This structure does not aim to present a strictly chronological or doctrinal development of Buddhist schools; rather, it reflects my particular interest and emphasis, especially on Zen Buddhism. Key branches like Theravāda, general Mahāyāna developments, and Vajrayāna Buddhism are touched upon or planned for future expansion. The lists below serve as both an overview and a navigational guide to explore the broad themes of Buddhist history, philosophy, and cultural expressions. These entries also define the structure and content of our article series, inviting deeper engagement with each topic across dedicated posts.

Intellectual and cultural background of early Buddhism

Before Buddhism emerged as a distinct tradition, the Indian subcontinent hosted a rich array of philosophical systems, ritual practices, and socio-religious upheavals. These movements and developments shaped the mental and cultural horizon from which Siddhartha Gautama’s insights arose and against which they defined themselves. Here is an overview of the key historical and intellectual contexts that influenced early Buddhism:

- Indian philosophy: An overview of ancient schools and concepts

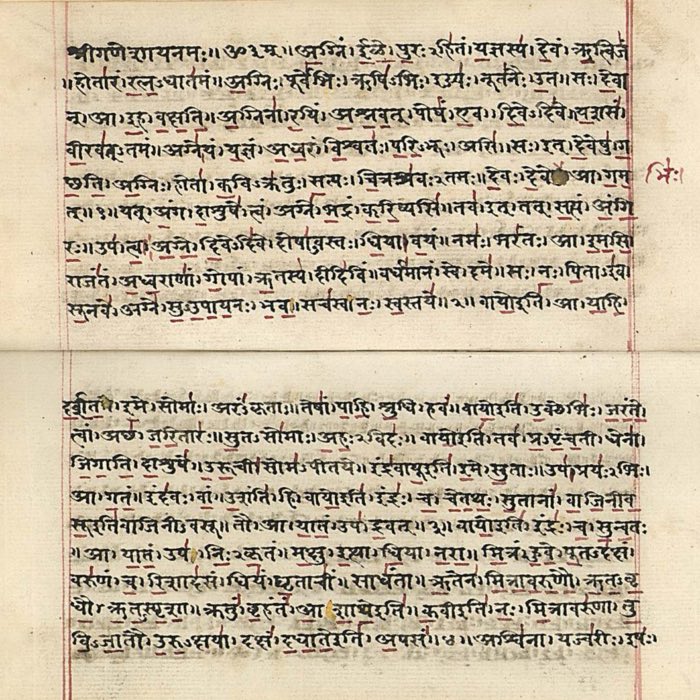

- The Vedas: Foundations of Indian civilization and spiritual thought

- Vedantic philosophy: The Upanishads and the Brahmanical tradition

- The second urbanization in ancient India: The rise of cities and the emergence of new religious movements

- The Sramana movements: The rise of asceticism and philosophical inquiry

- Buddhism: Philosophy or religion?

- The historical Buddha: Siddhartha Gautama

Buddhist core concepts

Foundational to all schools of Buddhism are concepts such as impermanence, non-self, and dependent origination — principles that challenge everyday assumptions about stability and identity. Together, they describe a process-like structure of existence, dissolve illusions of a fixed self, and lay the philosophical groundwork for liberation through insight, ethical action, and meditation:

- Dharma, the universal law or truth that governs existence

- The Four Noble Truths: The foundation of Buddhist teachings

- The Three Marks of Existence

- Dukkha: The core problem of existence

- Anatta: The illusion of self

- Tanha: Craving and attachment

- Upādāna, the clinging

- The Five Aggregates: The components that make up the illusion of a self

- The Three Poisons in Buddhist teachings: Greed, hatred, and delusion, that keep us in ignorance and thus prevent liberation

- Dependent Origination: The chain of causation that leads to suffering

- The Noble Eightfold Path: The path to liberation through ethical conduct, mental discipline, and wisdom

- Nirvana: The cessation of suffering

- Compassion and loving-kindness in Buddhism

- Samādhi: Meditation as the liberation from suffering

- The Middle Way: Avoiding extremes and finding balance

- Tathatā: Buddhism’s view on reality as it is

- Buddha-Nature (Tathāgatagarbha) and the process of awakening

- Avidyā: The Buddhist concept of ignorance

- Prajna: The wisdom of insight

- Sati: Mindfulness and its role in Buddhist practice

- Karma and Samsara in Indian thought and Siddhartha’s revolutionary reinterpretation

- The eight vijnanas: The Buddhist psychoanalysis

- Sīla – Buddhist ethics: The path of moral cultivation

- Upekkhā: The role of equanimity in Buddhist practice

- Upaya: The skillful means of teaching and practice

- The Three Jewels: The Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha

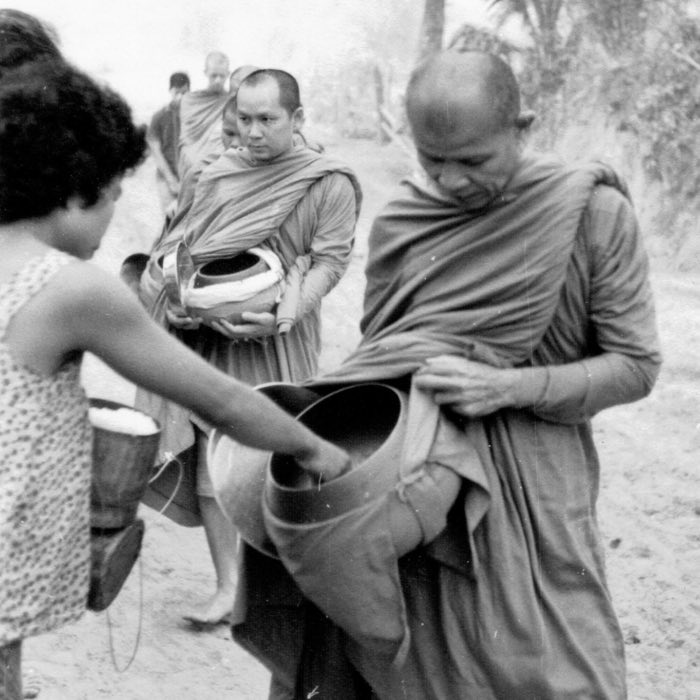

- The role of lay practitioners in Buddhism

- Written sources of Buddhism

- Three vehicles, three schools: How Buddhist teachings evolved and spread

- Going beyond the reachings: Buddhism as a path of transformation

Conceptual revolution by Nagarjuna

Nāgārjuna stands as one of the most influential Buddhist philosophers, offering a radical reinterpretation of core Buddhist doctrines through his philosophy of emptiness (śūnyatā). His thought, grounded in the principle of dependent origination, systematically dismantles all notions of intrinsic essence (svabhāva), opening the way to a profoundly non-essentialist view of reality. Through his foundational role in the Madhyamaka school, Nāgārjuna shaped Mahāyāna philosophy and deeply influenced later developments including Yogācāra and Chán/Zen:

- Nāgārjuna and his role in the development of Buddhist philosophy

- Śūnyatā and the Two Truths: Nāgārjuna’s Mādhyamika philosophy

- Interpenetration and the mirror of reality — From Dependent Origination to Huayan thought

- Nāgārjuna and the limits of conceptual thought: The unbinding of thought in Madhyamaka and its resonance in Zen

Beyond Nāgārjuna: Key developments in Mahāyāna philosophy

Building on the insights of Nāgārjuna, Mahāyāna Buddhism developed rich schools of thought such as Yogācāra. These later philosophical evolutions deepened the analysis of perception and experience, focusing on the workings of consciousness and its role in constructing reality. At the heart of this development is the idea that liberation arises from understanding and transforming the mind itself:

- Prajñāpāramitā literature and the language of emptiness

- The Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna: Unifying mind and suchness

- Asaṅga and Vasubandhu: Synthesizing Yogācāra thought

- Yogācāra and the nature of mind — Consciousness-only and the path to non-duality

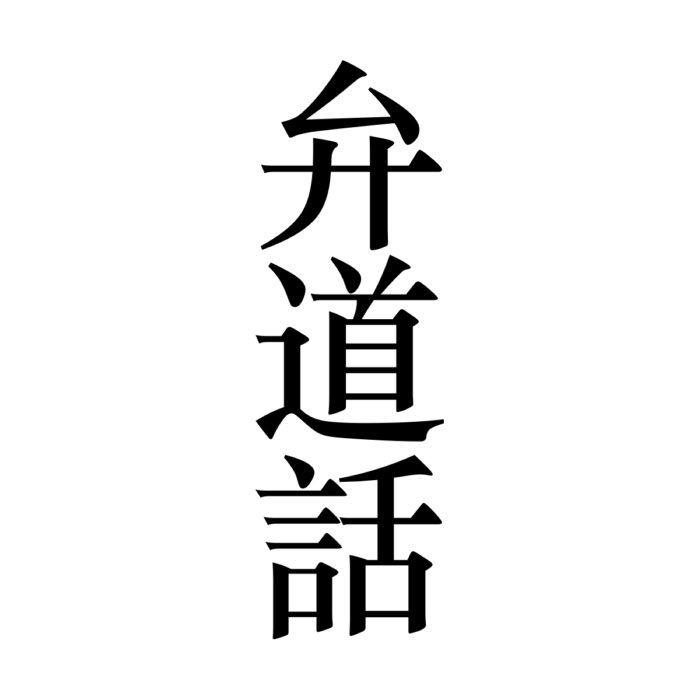

Chán/Zen Buddhism: Its development and contributions

Zen (Chán in Chinese) emphasizes direct experience, meditation, and the ineffability of awakening, favoring intuitive realization over analytical discourse. Its historical development and characteristic practices, from the legendary transmission by Bodhidharma to the formal systems of Japanese Rinzai and Sōtō, reflect a strong emphasis on practice over doctrine and embodiment over theory. Philosophically rooted in earlier Mahāyāna and Madhyamaka thought, Zen also integrates elements from Daoism and evolved into a distinct current within the broader Buddhist tradition:

- Zen: An overview of its historical and philosophical roots

- Foundations of Chán Buddhism:

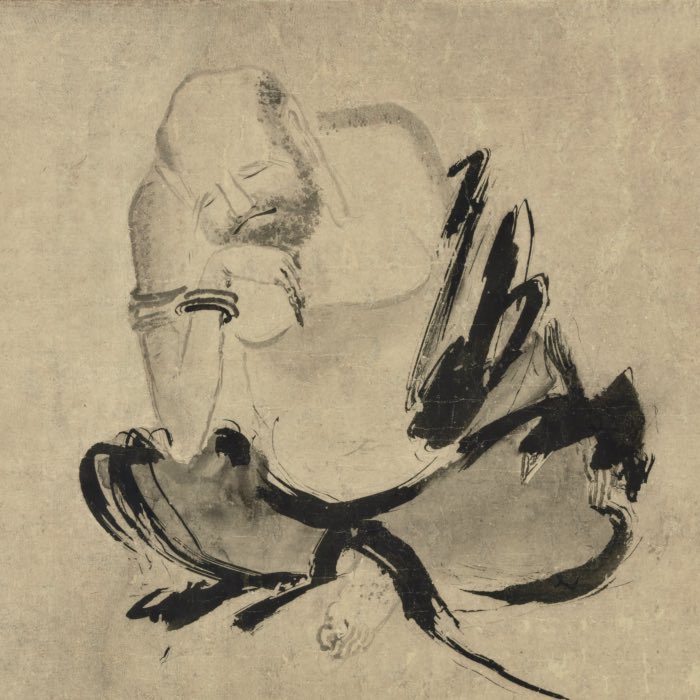

- Bodhidharma’s coming from the West: Reassessing the myth and its historical substance

- The Six Patriarchs of Zen: Foundations and transformations of the Chán tradition

- Dazu Huike: The second patriarch of Chán Buddhism and the embodiment of sincere seeking

- Sengcan: The third patriarch of Chán Buddhism and the spirit of equanimity

- Daoxin: The fourth patriarch and the institutional grounding of Zen

- Daman Hongren: The fifth patriarch and the maturation of East Mountain Zen

- Dajian Huineng: The sixth patriarch and the great divergence in Chinese Zen

- The Northern and Southern Schools of early Chinese Chán Buddhism

- The Five Houses of Chán: The diversification of Chinese Zen

- The influence of Daoism and Confucianism on Chán Buddhism

- Core concepts and practices:

- Zen’s way of knowing: From conceptual thought to direct realization

- Suchness as reality: Zen, tathatā, and the interplay of emptiness

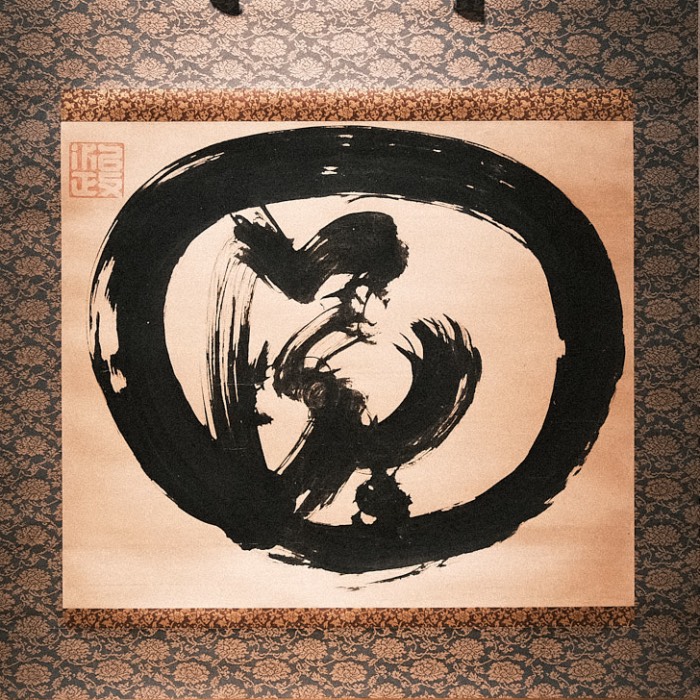

- The central element of Zen: Zazen

- Kenshō and Satori: Awakening in Zen

- Zen: Presence as practice

- The role of kōans in Zen

- The student-teacher relationship in Zen

- Dōgen Zenji and his significance for Zen Buddhism

- Mental qualities emphasized in Zen practice:

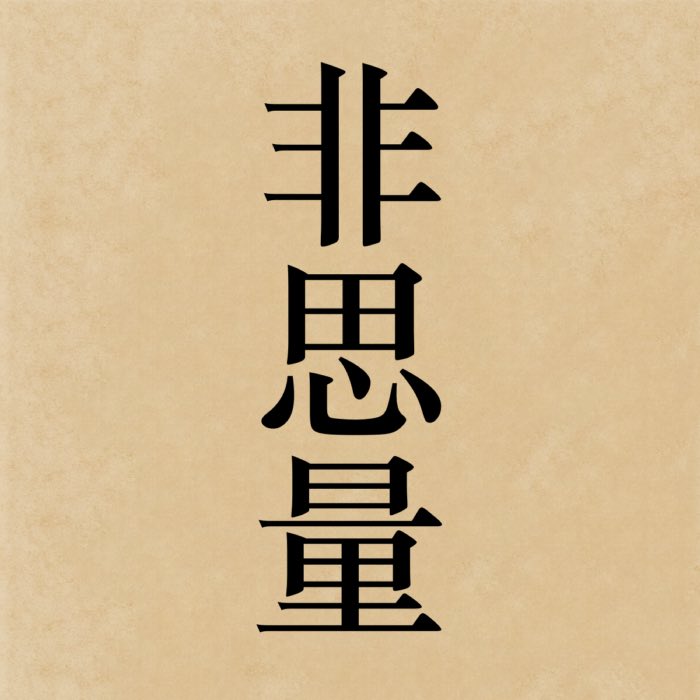

- Hishiryō: The Zen concept of non-thinking

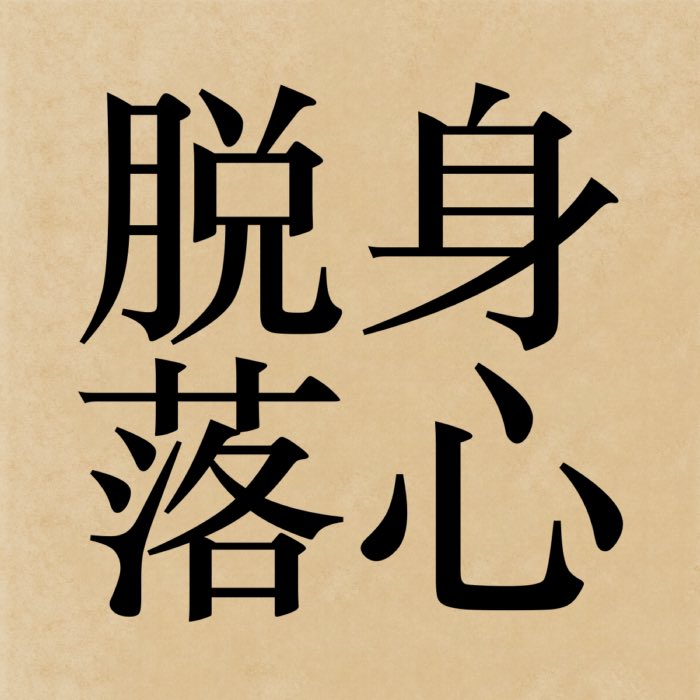

- Datsuraku: Dropping off body and mind

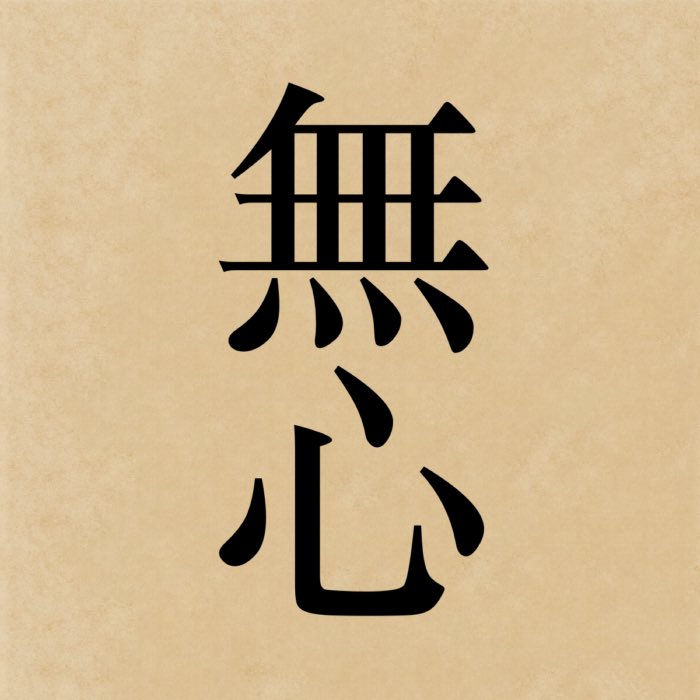

- Mushin: The Zen state of no-mind

- Samādhi: Meditative absorption in Zen

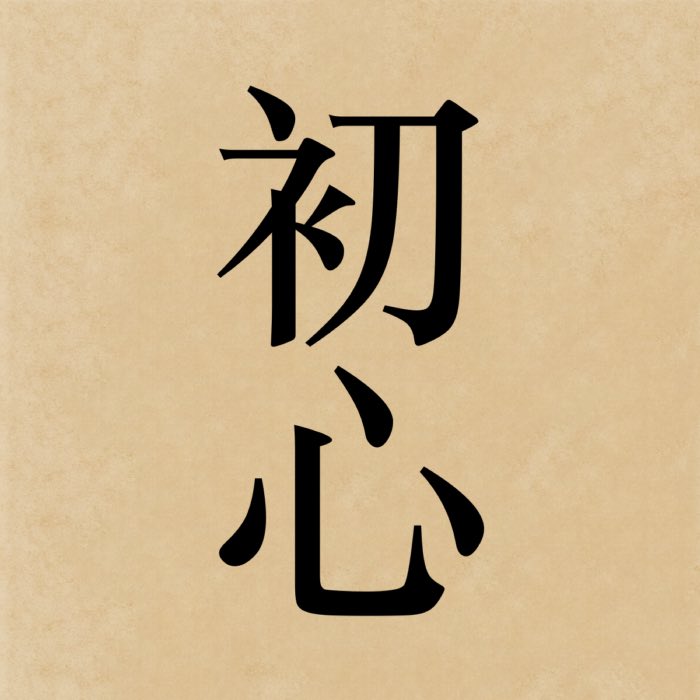

- Shoshin: The beginner’s mind in Zen

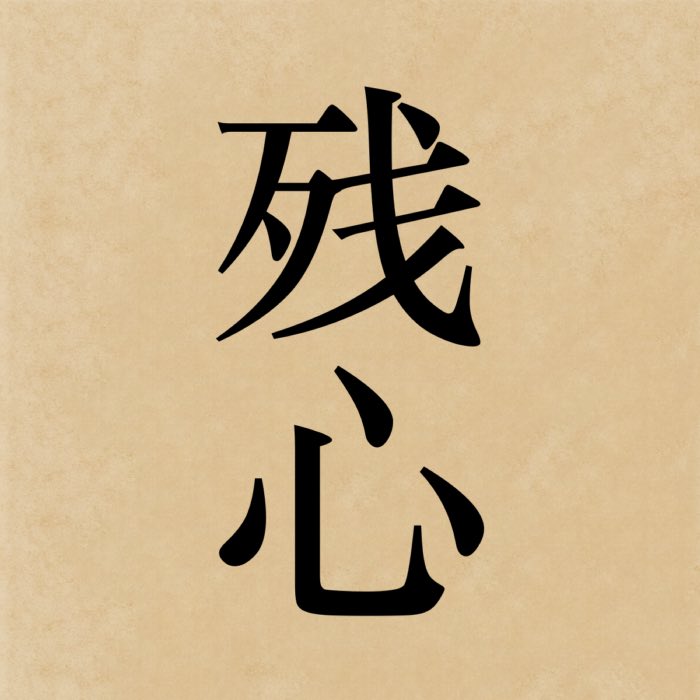

- Zanshin: Lingering awareness in Zen

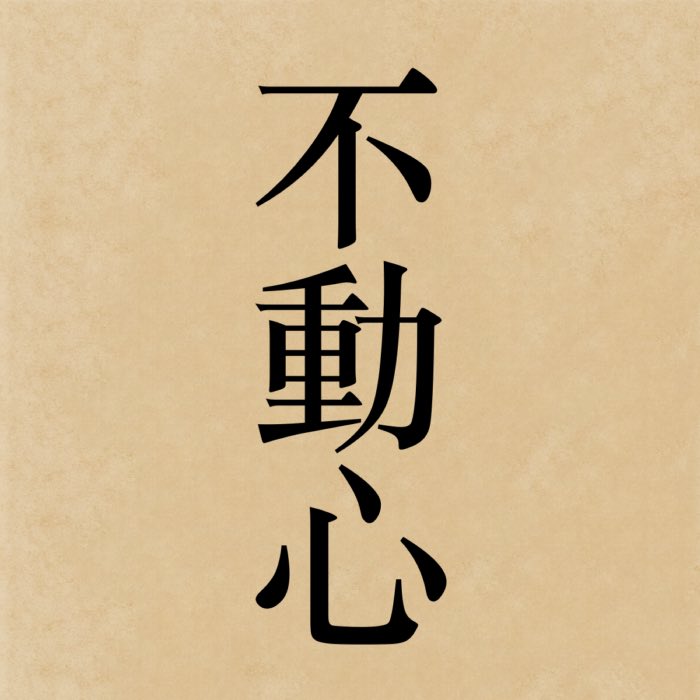

- Fudōshin: The immovable mind

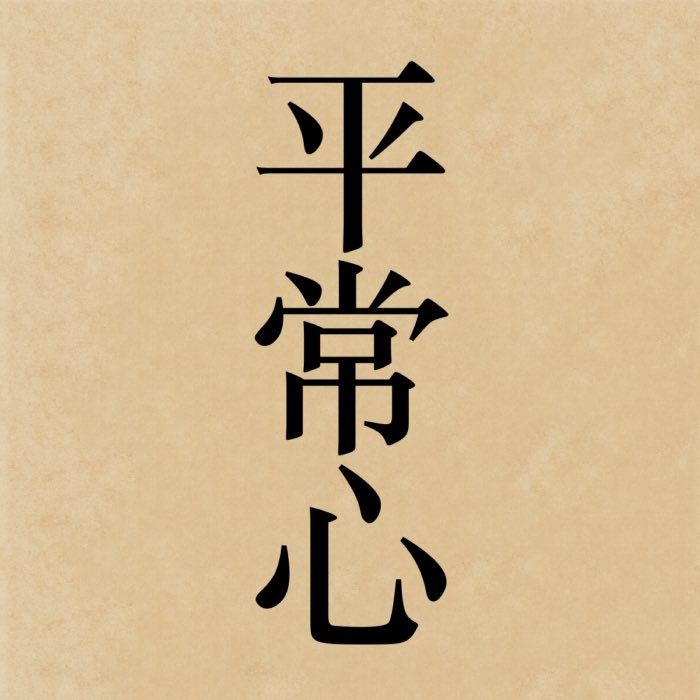

- Heijōshin: The everyday mind

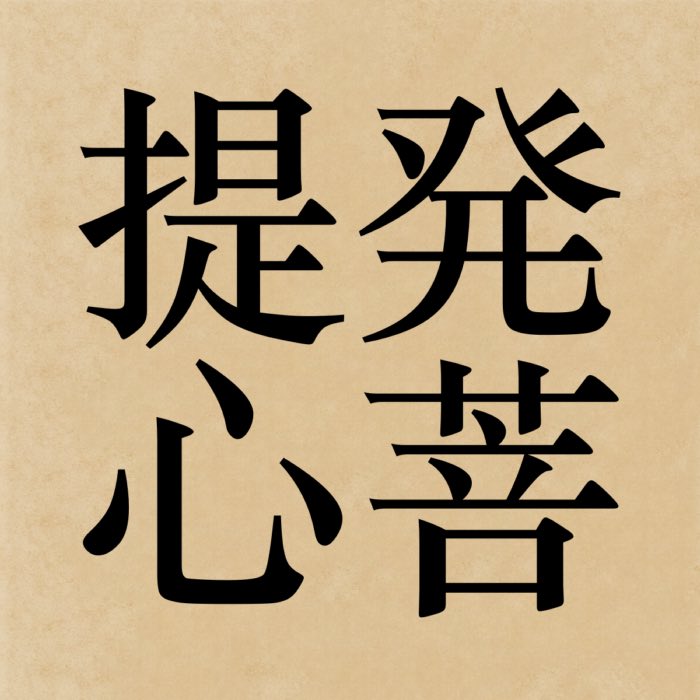

- Hotsu bodaishin: Arousing the mind of awakening

- Isshin: The undivided mind

- Shisei: Posture as mind-body presence in Zen

- Gaman: Enduring patience in Zen

- Kansha: Gratitude as a Zen practice

- Shingitai: The unity of mind, technique, and body

- Shinshin: The unity of mind and body

- Mosshōseki: What does it mean to leave no trace behind?

- Bankei’s ‘The Unborn’

- Hakuin Ekaku and his role in the revitalization of Rinzai Zen

- Daisetz Suzuki: Spreading Zen to the West and refreshing its spirit

- Shunryu Suzuki: Establishing Zen Practice in America

- Taisen Deshimaru and the transmission of Zen to Europe

Mythology and archetypes in Buddhist tradition

While rooted in rational analysis and meditative practice, Buddhism also developed a rich mythological world populated by Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, protectors, and other symbolic beings. These figures embody ethical ideals, meditative states, and cosmic functions, offering practitioners imaginative and devotional means to engage with the path of liberation:

- The Arhat: The ideal of liberation in early Buddhism

- The Bodhisattva: Mahāyāna ideal of compassion

- Bodhicitta: The heart of awakening

- What is a Buddha?

- Dharmapālas: Guardians of the Buddhist path

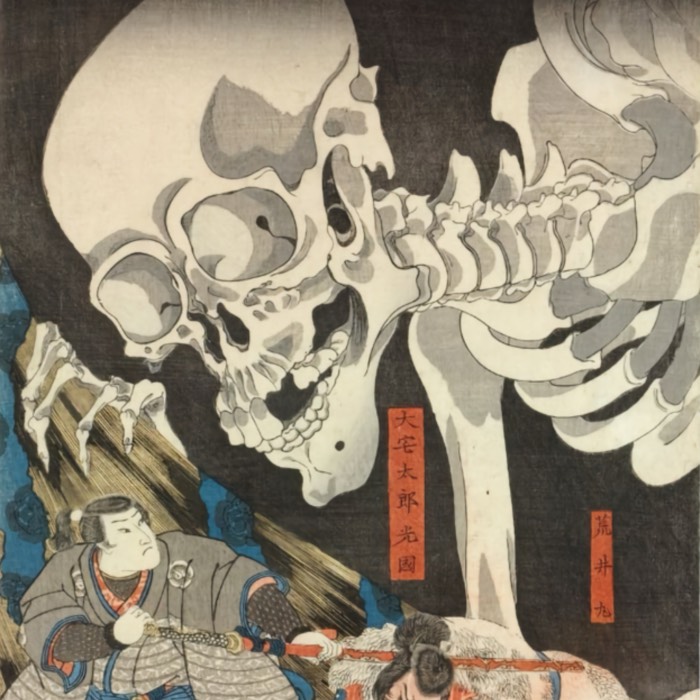

- Buddhist mythology: Symbol, function, and soteriological utility

- Buddhist hells

- Buddhist cosmology: Mount Meru and the Ocean of Milk

- Buddhist vs. Hindu cosmology: Inheritance, divergence, and polemical transformation

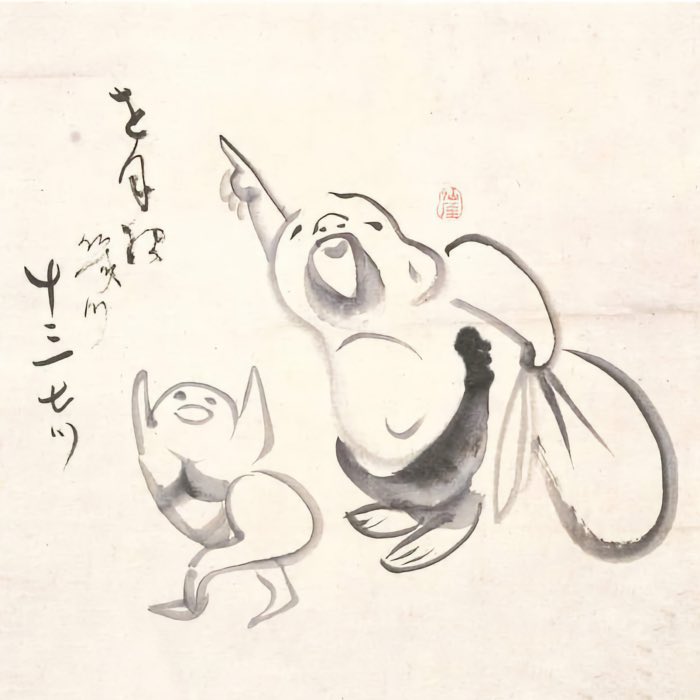

- The Jātakas: The tales of Siddhartha’s past lives

- Yakṣas, Nāgas, and other semi-divine beings in Buddhism

- Buddhist eschatology and the future Buddha Maitreya

- Adibuddhas and the Five Tathāgatas

- Avalokiteśvāra: The embodiment of compassion

- Amitābha Buddha: The Buddha of infinite light

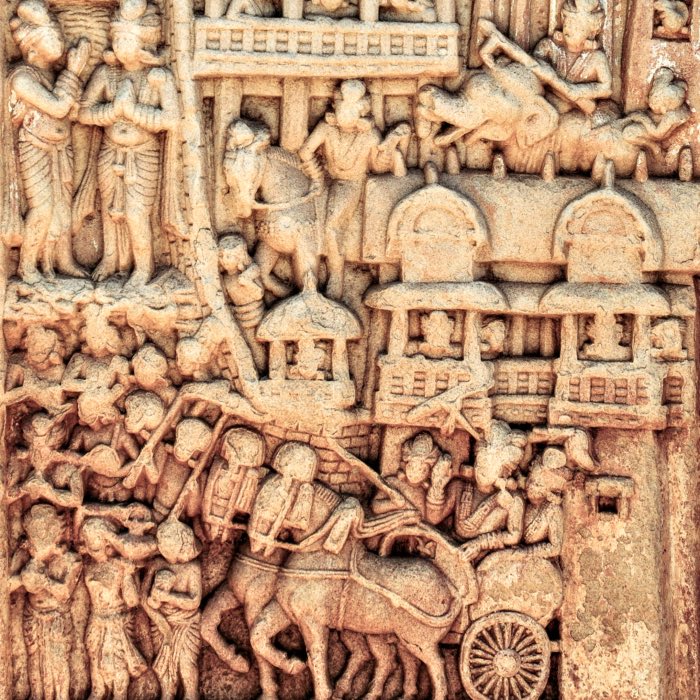

Art, architecture, and the institutional spread of Buddhism

Buddhism’s visual and spatial expressions played a crucial role in its transmission. Monasteries, stūpas, cave temples, and university complexes not only hosted religious life but also embodied key philosophical ideas and served as hubs of learning, art, and cross-cultural exchange. These architectural and artistic forms enabled Buddhism to take root in diverse cultural landscapes while preserving a shared symbolic and institutional foundation:

- Archaeology of Buddhist sites: Tracing the historicity of early Buddhism

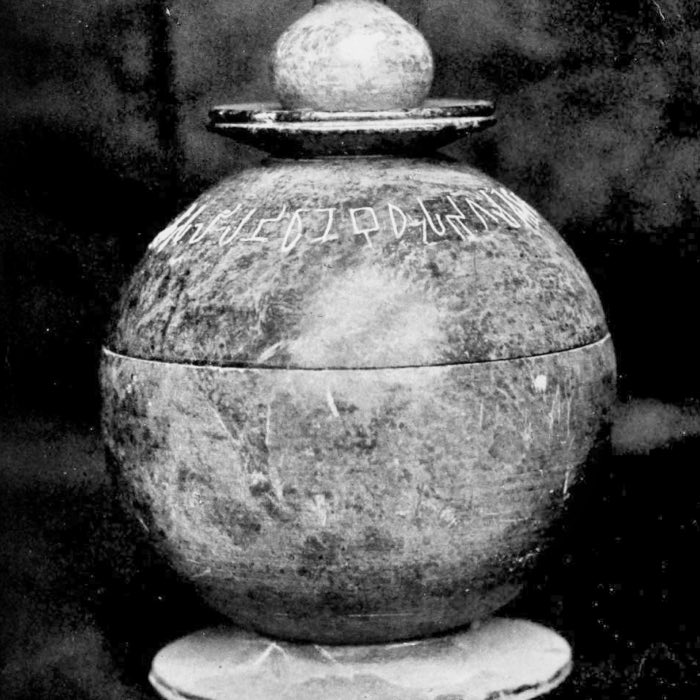

- Piprahwa: The Buddha’s relics and the history of their archaeological discovery

- Stūpas: Sacred architecture of Buddhism

- The earliest Buddhist monasteries

- Cave temples

- Buddhist universities: Innovation and transmission in monastic education

- Buddhist institutions and sacred sites across Asia, 500–1300 CE: Tracing the main phase of transregional and monumental institutional Buddhism

- Borobudur: A Buddhist mandala in stone

- Srivijaya: A Buddhist maritime empire in Southeast Asia

- Anurādhapura: Early Buddhist urbanism and monastic landscapes in Sri Lanka

- Bagan: The first unified polity of the Burmese heartland

- Angkor: The Khmer empire’s sacred center

- Bagan-era successor states: Buddhist continuities and regional transformations in myanmar

- Polonnaruwa: Buddhism, kingship, and urban renewal in medieval Sri Lanka

- Tibetan monastic sites: Samye, Sakya, and the foundations of institutional Buddhism in Tibet (8th–13th Century)

- Buddhist temple tradition in East Asia: China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam

- Monumental Buddhist architecture in the modern era

- Modern Buddhist monuments outside Asia

Cross-cultural encounters and transformations

Buddhism has continually transformed through encounters with other cultures and philosophies. Interactions with Hellenistic thought, Christian legends, and modern Western frameworks gave rise to new interpretations, hybrid forms, and renewed interest in core principles. These cross-cultural dialogues reveal Buddhism’s capacity to adapt while maintaining philosophical coherence:

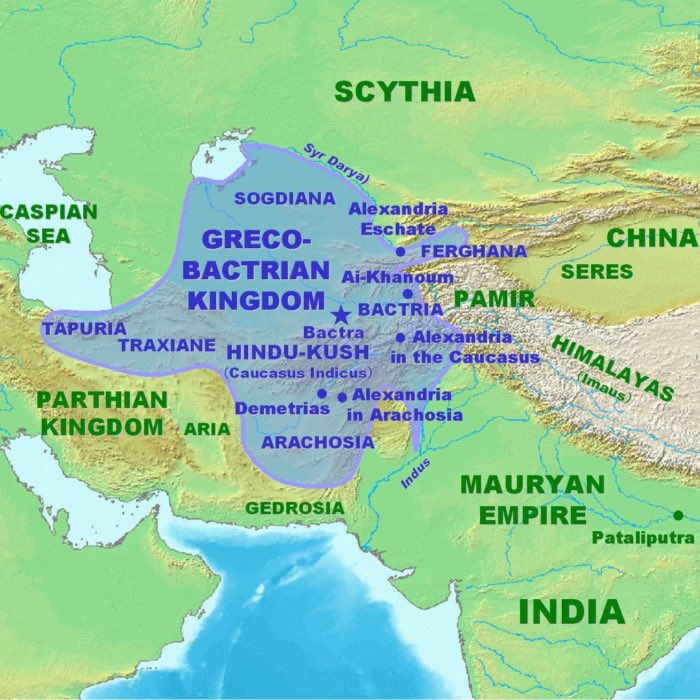

- Hellenistic encounters with India: Historical and cultural background

- Ai-Khanoum: The Greco-Buddhist city in Central Asia

- Menander I and the Milindapañha: Greek kingship and Buddhist philosophy

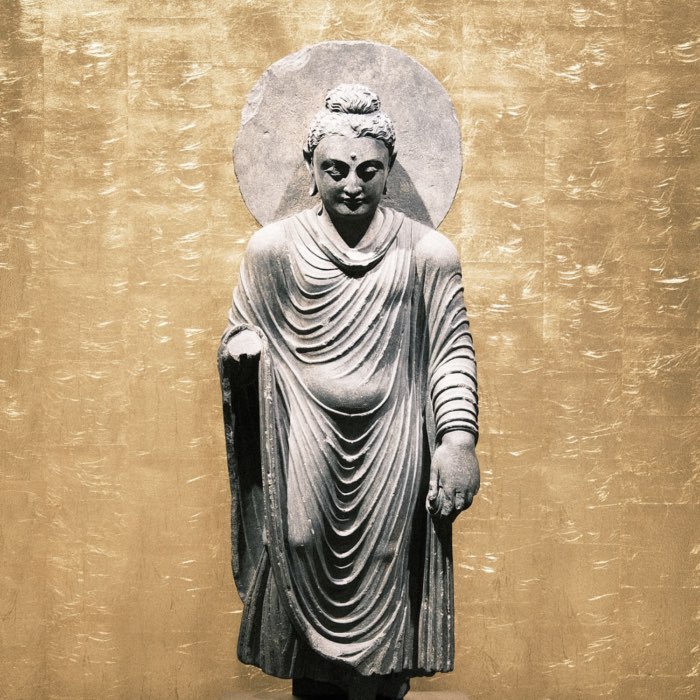

- Gandhāra: The Greco-Buddhist encounter and the birth of Buddhist figural art

- Buddha icons in unexpected places: Traces of Buddhist contact across Afro-Eurasia

- Barlaam and Josaphat: How Siddhartha became a Christian saint

- The first modern encounters between the West and Buddhism: Colonialism, rediscovery, and reform

Critical perspectives on Buddhism

Modern science, ethics, and social issues provide fresh angles to engage with Buddhist thought. Neuroscientific findings on consciousness and selfhood, ecological ethics, and debates on free will and moral agency all serve to reinterpret and test Buddhist insights in light of contemporary concerns. This ongoing dialogue reveals both convergences and tensions between traditional teachings and modern worldviews:

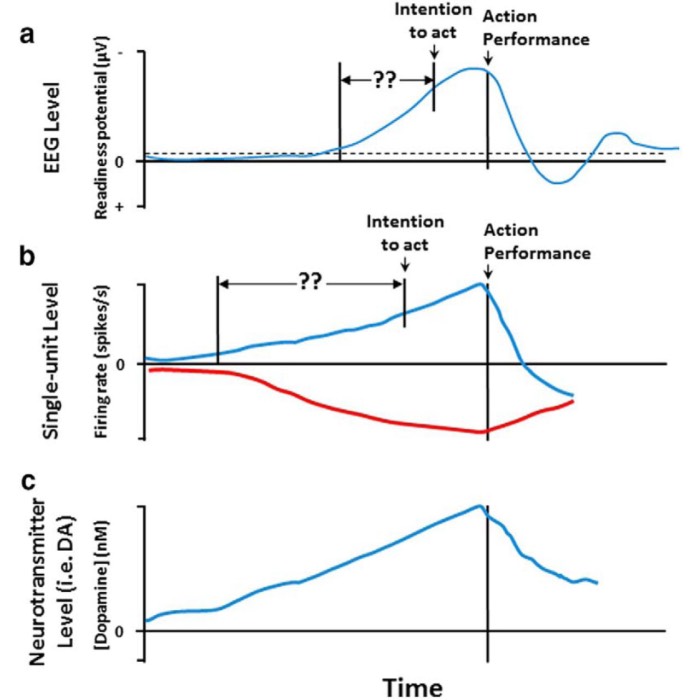

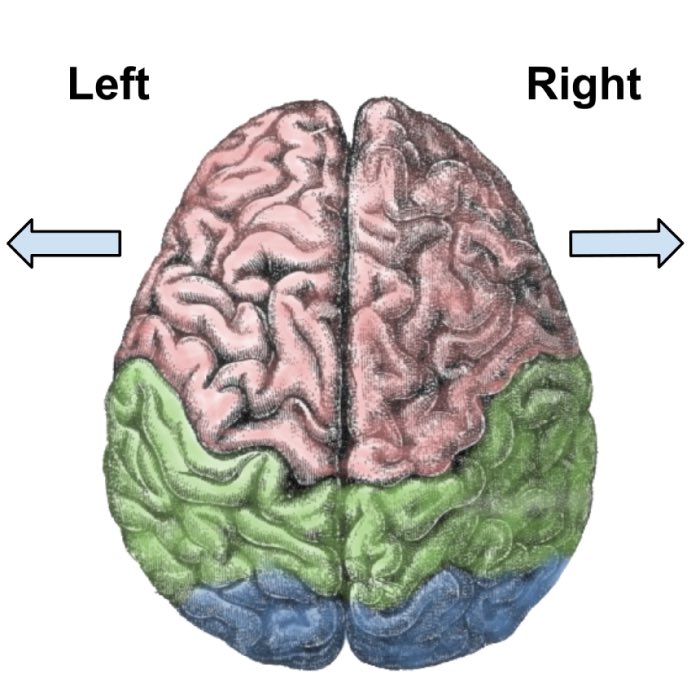

- Anattā and neuroscience: questioning the self through split-brain research

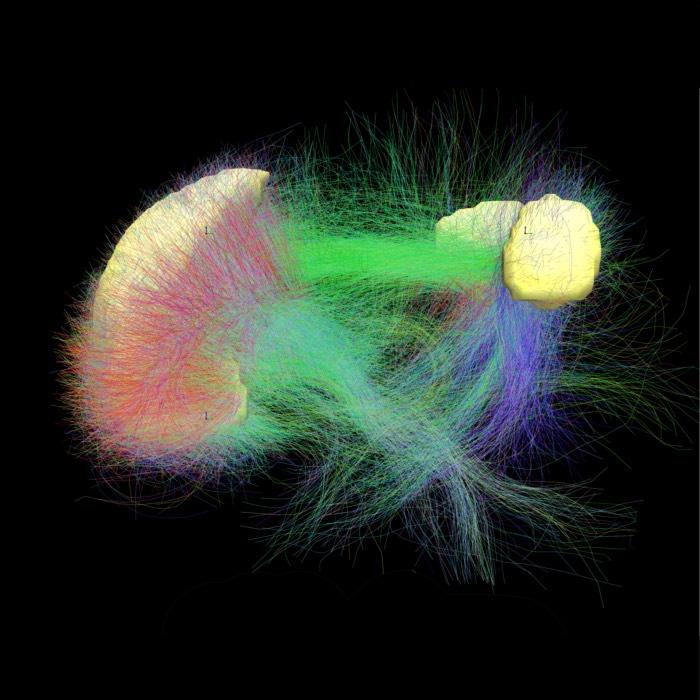

- How sustained meditation practice alters brain structure and function

- The illusion of free will and Buddhist ethics

- The default mode network and the dissolution of ego

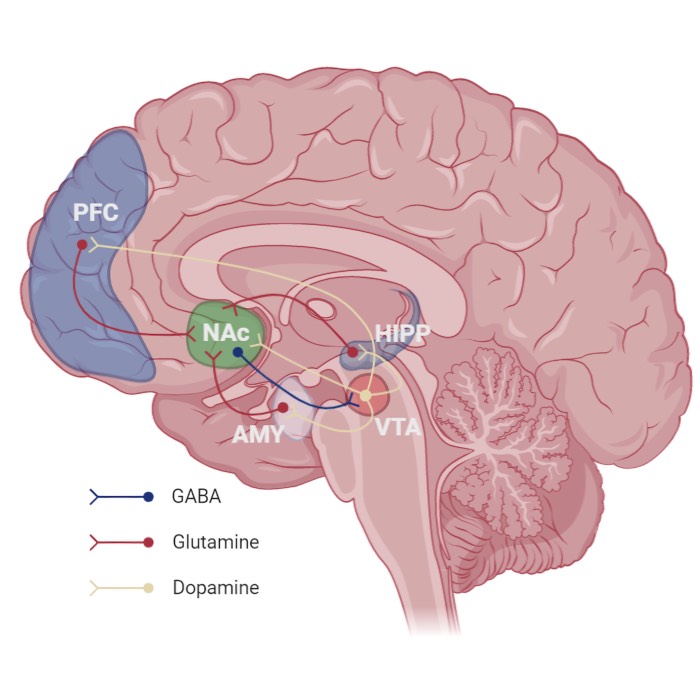

- Suffering, craving, and the brain’s reward system

- Consciousness and the ‘hard problem’ from a Buddhist angle

- Death, rebirth, and continuity of mind

- Buddhism and quantum physics: Parallels, projections, and problems

- Homosexuality and Buddhism: History, philosophy, and contemporary perspectives

- Buddhism and the environment: Impermanence, compassion, and climate responsibility

- Engaged Buddhism: Compassion in action

- Vegetarianism and Buddhism: Ethics, compassion, and practice

- Zen and Japanese militarism: Complicity and ethical failure

Historical overview

Buddhism did not emerge in a vacuum; its roots lie in the religious-philosophical ferment of late Vedic India. We will explore the historical context of Buddhism’s emergence and its further developments in the upcoming posts. The following list provides a brief overview of the historical periods and key events that help to navigate the complex history of Buddhism:

- 563 - 483 BCE: Life of Siddhartha Gautama Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha, is born in Lumbini (modern-day Nepal) and attains enlightenment in Bodh Gaya, India. After his awakening, he teaches the Dharma for over 40 years and passes away in Kushinagar. His teachings form the foundation of Buddhism.

- 483 BCE (approx.): First Buddhist Council

In Rajagriha, shortly after Siddhartha’s death, the first council is held to recite and codify his teachings. - c. 383 BCE: Second Buddhist Council

The second council is convened in Vaisali to address disputes over monastic discipline. - 268–232 BCE: Reign of Ashoka and Third Buddhist Council

Imperial patronage; Third Buddhist Council; widespread missions. - c. 165–130 BCE: Reign of Menander I

Greco-Bactrian king who embraced Buddhism and supported its spread in the Indo-Greek Kingdom. - c. 3rd–1st century BCE: Graeco-Buddhism

Cultural and artistic synthesis between Hellenistic and Buddhist traditions, centered in the Indo-Greek Kingdom and Gandhara. - 3rd century BCE: IntroductionSri Lanka

Buddhism introduced to Sri Lanka during the reign of Ashoka, traditionally attributed to the missionary Mahinda. - c. 29 BCE: Canonization of the Pali Tipitaka (Fourth Buddhist Council)

Key milestone in preserving early scriptures in Sri Lanka. - 1st century BCE: Formation of the Mahayana tradition

Emergence of texts emphasizing bodhisattva ideals. - 1st century: Ai-Khanoum

Important Greco-Bactrian city reflecting Buddhist and Hellenistic cultural exchange. - 1st–2nd century: Introduction to Central Asia

Carried along trade routes into regions like Bactria and the Tarim Basin. - c. 2nd century: Nāgārjuna and the Madhyamaka School

Philosophical developments on emptiness (śūnyatā). - 2nd–3rd century: Introduction to China

Initial spread through Silk Road exchanges, with translations of texts and establishment of early monastic communities. - 4th century: Introduction Korea

Introduced from China via the kingdom of Goguryeo. - c. 4th–7th century: Composition of the Heart Sūtra

One of the most influential Mahayana sutras. - 4th–5th century: Pure Land Buddhism emerges

Emerged in China around the 4th–5th century CE (notably associated with Huiyuan in the early 5th century); later popularized in Japan by figures such as Hōnen (1133–1212) and Shinran (1173–1263). - 5th–6th century: Bodhidharma

Traditionally regarded as the founder of Chán (Zen) Buddhism in China. - 5th–7th century: Introduction to Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia)

Mixed transmission routes, including both overland Mahayana influence from China and maritime Theravāda influence from South Asia. - 5th–13th century: Nālandā and Vikramaśīla (India)

Nālandā (5th–12th century) and Vikramaśīla (8th–13th century) emerge as major centers of monastic education and scholasticism in eastern India. They played a foundational role in preserving and transmitting Buddhist thought, including Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna teachings, across Asia. - 5th-7th century: The Six patriarchs of Chán

- 6th century: Buddhism arrives in Japan

Transmitted from Korea (Baekje). - 6th–7th century: Tiantai/Tendai

Founded by Zhiyi (538–597) in China; introduced to Japan by Saichō (767–822) in the early 9th century. - 7th century: Berenike Buddha

The discovery of a 7th centutry Buddha statue at Berenike, Egypt, in 2018 illustrates trade and cultural links between India and the Mediterranean. - 7th–8th century: Introduction to Tibet

Brought from India (Nālandā tradition) during the reign of King Songtsen Gampo and solidified under King Trisong Detsen. - 7th–13th century: Srivijaya (Sumatra)

The maritime empire of Srivijaya becomes a central Mahāyāna/Vajrayāna hub in maritime Southeast Asia, maintaining close ties with Nālandā and facilitating transmission to Java and beyond. - 8th century: Rise of Vajrayāna in Tibet

Introduction and establishment of Tantric Buddhism. - 8th–9th century: Borobudur (Java)

Constructed under the Sailendra dynasty, Borobudur exemplifies Mahāyāna-Vajrayāna cosmology through monumental architecture and narrative reliefs. It becomes a major site of ritual and pilgrimage. - 8th–13th century: Samye and Sakya (Tibet)

Samye (late 8th c.) is founded as the first monastery in Tibet, marking the institutional establishment of Buddhism on the plateau. Sakya rises to prominence in the 11th–13th centuries, producing influential texts and serving as a political-religious authority under Yuan rule. - 9th–13th century: Bagan (Myanmar)

Under King Anawrahta, Bagan becomes a major Theravāda center, with extensive temple-building and textual reform. It plays a decisive role in the consolidation of Theravāda Buddhism in mainland Southeast Asia. - Early 9th century: Shingon

Established by Kūkai (774–835) in early 9th-century Japan, emphasizing esoteric or Tantric practices. - 9th century: Rinzai School (Linji)

Founded by Linji Yixuan (d. 866) in China; later transmitted to Japan. - 11th–12th century: Kagyu (Tibetan)

Developed by Marpa (1012–1097) and refined by Milarepa (1052–1135), known for its oral lineage. - 11th–13th century: Polonnaruwa (Sri Lanka) As the new capital of Sri Lanka, Polonnaruwa becomes a hub of Theravāda monastic reform and state-monastic cooperation. King Parākramabāhu I implements major Vinaya and saṅgha reforms.

- 1073: Sakya (Tibetan)

Founded in 1073 by Khön Könchok Gyalpo, focusing on scholarship and tantric practice. - 12th–13th century: Angkor (Cambodia) During the reign of Jayavarman VII, Mahāyāna Buddhism becomes the state religion. Grand monuments like Bayon reflect the integration of Buddhist imagery into Khmer imperial architecture. A later shift to Theravāda Buddhism begins in the 13th century.

- 13th century: Dōgen and the Sōtō School

Dōgen (1200–1253) establishes Sōtō Zen in Japan. - 13th century: Nichiren

Founded by the monk Nichiren (1222–1282) in 13th-century Japan, emphasizing the Lotus Sūtra as the sole vehicle of salvation. - 13th century: Jōdo Shinshū

A branch of Pure Land founded by Shinran (1173–1263) in 13th-century Japan, emphasizing salvation by faith in Amida Buddha. - Late 14th century: Gelug (Tibetan)

Founded by Je Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), known for its emphasis on monastic discipline. - 19th–20th century: Spread to Western countries

Buddhism introduced through immigration, academic study, and interest in Eastern philosophy. - 19th century: Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki

Scholar and popularizer of Zen Buddhism in the West. 20th century: Shunryu Suzuki Zen master who played a key role in establishing Zen practice in the United States. - 20th century: Thich Nhat Hanh Vietnamese Zen master and peace activist known for his teachings on mindfulness and Engaged Buddhism.

- 20th century: Taisen Deshimaru

Japanese Zen master who brought Sōtō Zen to Europe. - 20th century: Buddhādasa

Buddhādasa (1906–1993) was a prominent Thai reformer advocating a rational and socially Engaged Buddhism. - 2th century: Dalai Lama

The 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, is a key figure in Tibetan Buddhism and a global advocate for peace and compassion. - 20th century: Engaged Buddhism A movement emphasizing social action and ethical engagement, often associated with figures like Thich Nhat Hanh and the Dalai Lama.

Conclusion

Buddhism is both a philosophical system and a spiritual tradition that originated in ancient India and gradually spread across much of Asia and, eventually, the world. At its core, Buddhism addresses the nature of suffering (dukkha) and offers a clear, practical path to overcome it. Unlike the Abrahamic religions, Buddhism does not center around a creator god or divine commandments, but rather around a deep investigation of human experience and the development of ethical conduct, meditative discipline, and wisdom. Central to all Buddhist schools is the Dharma, the universal law that describes both the nature of reality and the way of life aligned with that reality. Over time, Buddhism evolved into a diverse family of traditions, but all share this core concern: understanding and overcoming suffering.

Building on this foundation, Buddhist practice is grounded in the insight that both the self and the world are processes — impermanent, conditioned, and without fixed essence. Liberation comes not through belief, but through directly seeing this reality and aligning one’s life with it. By investigating the nature of reality — through the lenses of impermanence, no-self, and the workings of karma — Buddhist teachings guide practitioners toward insight, ethical conduct, and meditative discipline. Taken together, these foundational ideas have shaped a wide spectrum of Buddhist traditions, which, despite their diversity across regions and eras, all remain rooted in the shared goal of understanding suffering and cultivating the wisdom and compassion necessary for liberation.

This introduction is only the starting point for our broader exploration. In the upcoming posts, we will examine the historical evolution, the regional adaptations, and the philosophical developments that emerged as Buddhism spread across Asia and beyond. We will also take a closer look at the practices and worldviews that define Theravāda, Mahāyāna, Vajrayāna, and Zen, alongside Buddhist ethics, mythology, and its relevance in the modern world. Stay tuned.

References and further reading

Introductory books

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

Reference works

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Robert E. Buswell, William M. Bodiford, Donald S. Lopez, John S. Strong, Eugene Y. Wang, Encyclopedia of Buddhism, 2004, Vol. 1 and 2, Macmillan Reference, ISBN: 978-0028657189

- Keown, Damien, A dictionary of Buddhism, 2003, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0-19-860560-7

- Notz, Lexikon des Buddhismus, 2002, Marixverlag, ISBN-10: 3932412087

- Robert E. Buswell, William M. Bodiford, Donald S. Lopez, John S. Strong, Eugene Y. Wang, Encyclopedia of Buddhism, 2004, Vol. 1 and 2, Macmillan Reference, ISBN: 978-0028657189

Source texts

- Most Buddhist suttas are freely available in various languages online. The most important pages are:

- Wilhelm Geiger, Die Reden des Buddha - Gruppierte Sammlung Saṃyutta-nikāya, 1997, Beyerlein-Steinschulte, ISBN: 9783931095161

- Karl Neumann (Übers.), Die Reden des Buddha - Sammlungen in Versen, 2015, Stammbach: Beierlein-Steinschulte, ISBN: 9783931095956

- Karl Neumann (Übers.), Die Reden des Buddha - Längere Sammlung, 1996, Beyerlein-Steinschulte, ISBN: 9783931095154

- Karl Neumann (Übers.), Die Reden des Buddha - Mittlere Sammlung, 1995, Beyerlein-Steinschulte, ISBN: 9783931095000

- Nyanatiloka Mahathera (Übers.), Die Lehrreden des Buddha aus der Angereihten Sammlung, 2013, Stammbach: Beierlein-Steinschulte, ISBN: 978-3-931095-88-8

- Bhikkhu Bodhi, The connected discourses of the Buddha - A new translation of the Samyutta Nikaya, 2003, Wisdom Publications, ISBN: 9780861713318

- Bhikkhu Bodhi, The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha - A complete translation of the Anguttara Nikaya, 2012, Wisdom Publications, ISBN: 9781614290407

- Bhikkhu Bodhi, In the Buddha’s Words - An anthology of discourses from the Pali Canon, 2005, Wisdom Publications, ISBN: 978-0861714919

- Bhikkhu Nanamoli, Bhikkhu Bodhi, The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha - A translation of the Majjhima Nikaya, 1995, Wisdom Publications, ISBN: 9780861710720

- Ilse-Lore Gunsser, Reden des Buddha: Aus dem Palikanon, 2008, P. Reclam, ISBN: 978-3-15-019302-0

- Klaus Mylius, Die vier edlen Wahrheiten - Texte des ursprünglichen Buddhismus, 1998, Reclam, ISBN: 9783150034200

comments