Written sources of Buddhism

The Buddhist textual tradition is among the richest in world religions, encompassing a wide range of genres, languages, and historical contexts. Buddhist teachings were originally transmitted orally for several centuries, preserved through rigorous memorization and recitation by monastic communities. Only later, in response to political and environmental threats to this oral tradition, were they written down. This transition from oral to written form marks a crucial moment in Buddhist history, not only safeguarding the teachings but also shaping their interpretation and institutional role. The resulting body of texts — spanning languages, regions, and centuries — offers a unique record of how Buddhist ideas were preserved, transformed, and systematized across time and cultures.

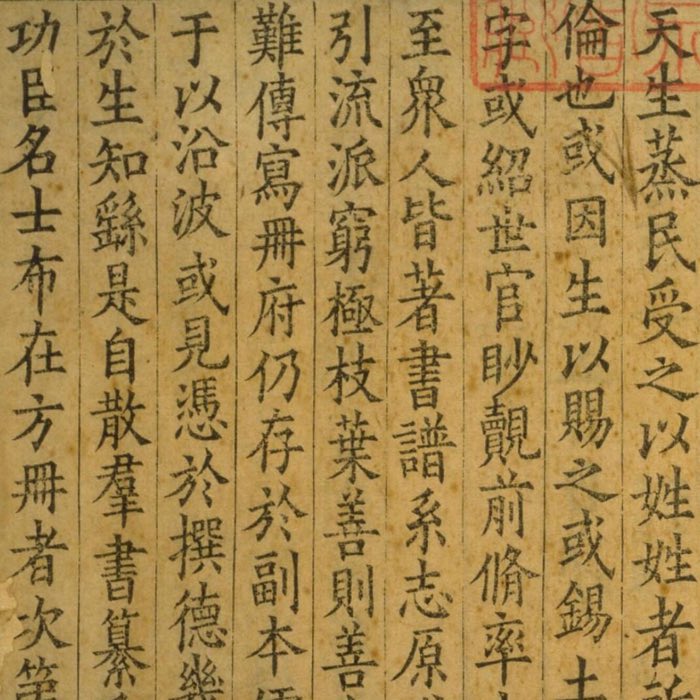

Palm-leaf manuscripts at the Batticaloa museum in Batticaloa, Sri Lanka. These traditional manuscripts exemplify one of the earliest and most enduring writing materials used to preserve Buddhist teachings in South and Southeast Asia. Inscribed with a stylus and blackened with soot or ink for legibility, palm-leaf texts were typically bound with string and stored in protective covers. They played a central role in the transmission of the Tipiṭaka and other canonical texts before the advent of printed editions. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Palm-leaf manuscripts at the Batticaloa museum in Batticaloa, Sri Lanka. These traditional manuscripts exemplify one of the earliest and most enduring writing materials used to preserve Buddhist teachings in South and Southeast Asia. Inscribed with a stylus and blackened with soot or ink for legibility, palm-leaf texts were typically bound with string and stored in protective covers. They played a central role in the transmission of the Tipiṭaka and other canonical texts before the advent of printed editions. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Oral origins and early codification

Initially, the teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama were not committed to writing. In accordance with cultural norms in ancient India, these teachings were preserved and transmitted orally by monastic communities through rigorous memorization and frequent communal recitations. Specific mnemonic devices and formulaic structures were used to aid memory and ensure consistency. The teachings were grouped according to themes such as ethics, meditation, and philosophical reflection, and were passed down from generation to generation within tightly knit monastic lineages.

Despite these efforts, oral transmission is inherently susceptible to change over time. Phrases could be altered, passages forgotten, and new interpretations introduced, whether intentionally or not. However, many scholars believe that the core elements of early Buddhist doctrine — such as the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path, and the emphasis on impermanence and non-self — have been reliably preserved.

The first known effort to write down the teachings occurred in Sri Lanka during the reign of King Vattagāmaṅi Abhaya in the 1st century BCE. Faced with political instability and natural disasters that threatened the continuity of the oral tradition, monastic leaders gathered to commit the teachings to writing. This effort produced the Pāli Canon, or Tipiṭaka (“Three Baskets”), which became the foundational scripture of the Theravāda tradition.

The Pāli Canon

The Pāli Canon remains the most complete early collection of Buddhist texts. It is written in Pāli, a Middle Indo-Aryan language closely related to the spoken vernaculars of Siddhartha’s time, though not identical to them. The canon is referred to as the Tipiṭaka, meaning “Three Baskets,” and divided into three sections: the Vinaya Piṭaka (monastic discipline), the Sutta Piṭaka (discourses), and the Abhidhamma Piṭaka (systematic philosophical and psychological analysis). The Vinaya Piṭaka outlines rules and procedures for monastic life, including detailed prescriptions for ethical conduct and the organization of the monastic community. The Abhidhamma Piṭaka presents a more abstract and systematic analysis of mental processes and doctrinal categories, forming the basis for later scholastic traditions.

The Sutta Piṭaka contains many of the discourses attributed to Siddhartha, including well-known texts such as the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, which outlines the Four Noble Truths. While scholars widely agree that the Pāli Canon contains material that can plausibly be traced back to the historical Siddhartha, it is also clear that layers of interpretation and redaction have shaped its final form.

Sanskrit and other canons

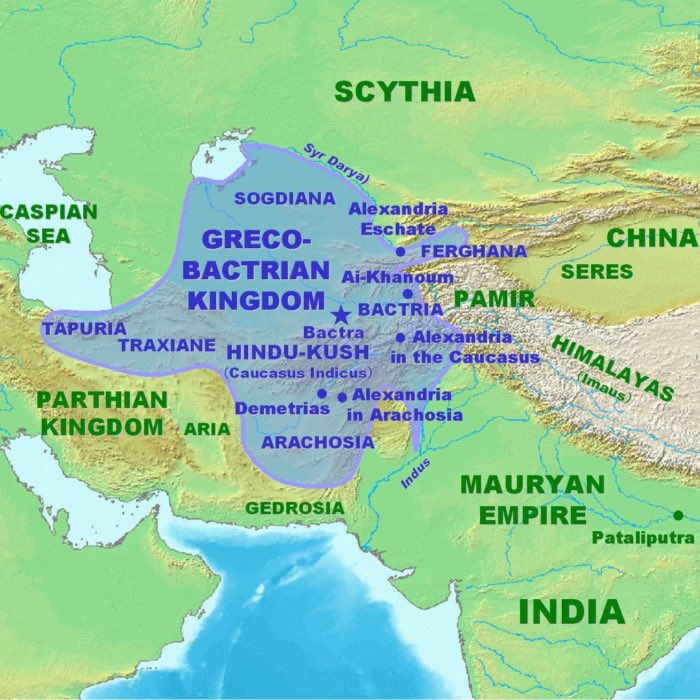

As Buddhism spread across Asia, its textual traditions diversified. In the northwest of the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia, Buddhist texts were composed and preserved in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and hybrid dialects. These texts often reflect the development of the Mahāyāna tradition, which introduced new philosophical ideas, cosmologies, and devotional practices.

The Sanskrit canon is not a single, unified body like the Pāli Canon, but consists of a wide range of texts including sutras, commentaries, and philosophical treatises. Notable examples include the Prajñāpāramitā (Perfection of wisdom) literature and the Lotus Sūtra, both of which had a significant impact on East Asian Buddhism. These texts were often preserved through translations into Chinese and Tibetan, as the original Sanskrit manuscripts were lost or fragmented over time.

Chinese Buddhist canon

With the arrival of Buddhism in China beginning in the Han dynasty (2nd century CE), translation efforts began on a massive scale. Chinese monks traveled to India in search of original Sanskrit texts and oral teachings, which they then helped translate upon returning. These pilgrimages were instrumental in enriching the Chinese understanding of Buddhist doctrine and were often facilitated by the routes of the Silk Road, which enabled the movement of people, texts, and ideas between India and East Asia.

Indian monks such as Kumārajīva also played a pivotal role in rendering Sanskrit texts into Chinese, leading to the creation of a voluminous Chinese Buddhist canon. This canon, known as the Dàzàngjījīng, grew over centuries and now contains thousands of texts. It includes translations of early suttas, Mahāyāna scriptures, esoteric (Tantric) works, and indigenous Chinese compositions. The Chinese canon is also notable for its inclusion of commentarial literature and treatises by Chinese Buddhist philosophers who contributed to schools like Tiantai, Huayan, and Chán.

Korean Buddhist canon

Korea played a significant role in the transmission and preservation of Buddhist texts, often acting as a cultural bridge between China and Japan. While Korea adopted much of its Buddhist textual heritage from Chinese sources, Korean monks also contributed to the canon’s organization and distribution, particularly during the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392).

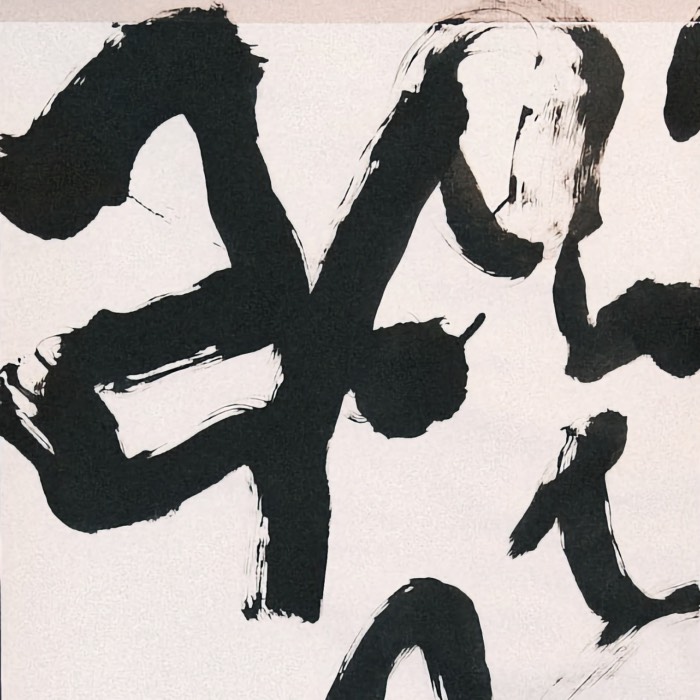

The most remarkable achievement in Korean Buddhist textual history is the Tripitaka Koreana, a complete woodblock edition of the Buddhist canon in classical Chinese. Commissioned in the 13th century as an offering to protect the nation from Mongol invasions, it consists of more than 80,000 meticulously carved wooden printing blocks. Housed at the Haeinsa Temple, the Tripitaka Koreana is celebrated for its textual accuracy, calligraphic beauty, and preservation. Unlike other versions of the canon, it was not based on a single earlier edition but compiled through comparison with multiple source texts, resulting in a uniquely authoritative version.

Korean Buddhism also developed its own scholastic and ritual texts, particularly within the Seon (Zen) tradition. These writings, although often produced in classical Chinese, addressed local doctrinal concerns and practices, reflecting the adaptive nature of the Buddhist tradition in the Korean context.

Japanese Buddhist canon

Japan inherited much of its Buddhist textual tradition from Chinese and Korean sources, but over time developed its own distinctive canonical framework. While there is no single, standardized Japanese Buddhist canon akin to the Chinese Dàzàngjījīng or the Tibetan Kangyur and Tengyur, Japanese Buddhist institutions preserved and adapted a wide range of texts from various traditions, especially those of Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna origin.

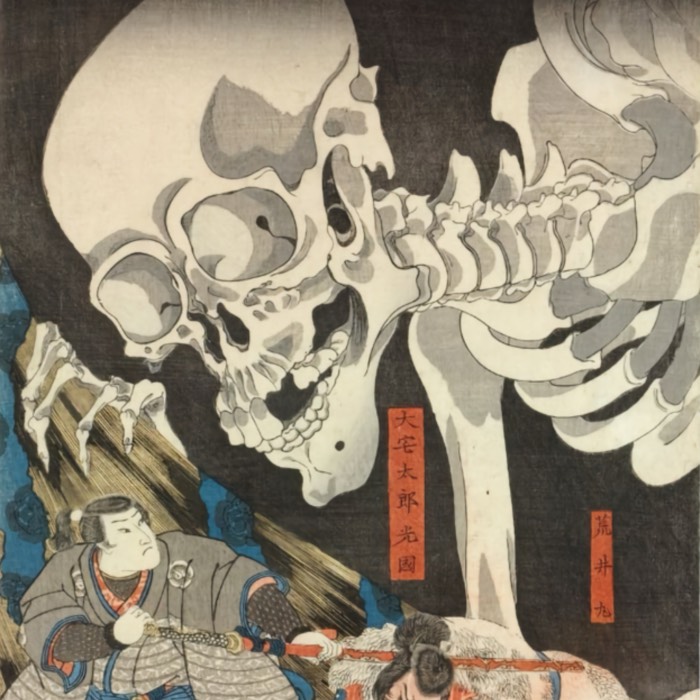

The Tendai and Shingon schools, established in the 9th century, relied heavily on Chinese translations of Mahāyāna sutras and esoteric scriptures, but they also contributed original commentaries and ritual manuals. During the Kamakura period (12th–14th centuries), reformist movements such as Pure Land (Jōdo), Nichiren, and Zen emphasized particular texts as central to their practice. For example, the Larger Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra became foundational for Pure Land Buddhism, while Nichiren Buddhism revolved almost entirely around the Lotus Sūtra, which was viewed not just as scripture but as a living expression of the Dharma.

Japanese Buddhist texts were often produced in vernacular language or kanbun (classical Chinese adapted for Japanese readers), and many were disseminated through temple printing operations. With the rise of woodblock printing in the Edo period, Buddhist literature became more widely available to the public, and commentarial traditions flourished.

While the Japanese canon is closely tied to the Chinese transmission, it demonstrates a high degree of selectivity, innovation, and institutional diversification. This reflects Japan’s unique religious landscape, in which doctrinal schools operated alongside localized ritual practices and temple-based social functions.

Tibetan Buddhist canon

Buddhism entered Tibet in the 7th century CE, where it encountered a different linguistic and cultural environment. The Tibetan Buddhist canon is divided into two major collections: the Kangyur (translated words of the Buddha) and the Tengyur (commentarial and scholastic works). Unlike the Pāli Canon, these texts were not exclusively based on early Buddhism but largely derived from Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions.

Tibetan translators, working with Indian scholars, created meticulous glossaries and developed a standardized technical vocabulary, which made Tibetan an important language for preserving Buddhist philosophy. The Tibetan canon contains translations of many works that are no longer extant in their original Sanskrit versions, making it a vital source for understanding the later developments of Indian Buddhism.

Apocryphal and vernacular texts

In addition to the major canonical collections, Buddhism has produced a wide range of apocryphal and vernacular texts. These include local scriptures, folk narratives, and devotional literature written in languages such as Japanese, Korean, Thai, Burmese, and others. Some of these texts were composed in imitation of canonical sutras, while others reflect popular adaptations of Buddhist themes.

For instance, in East Asia, new sutras occasionally appeared that claimed Indian origin but were likely composed locally to address particular doctrinal or institutional needs. Examples include the Śūraṇgama Sūtra and the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, which exhibit distinctively Chinese philosophical concerns. In the case of Japanese Buddhism, schools such as Pure Land and Nichiren developed their own scriptural traditions around texts like the Larger Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra or the Lotus Sūtra, emphasizing faith and practice over scholasticism.

Writing materials and technologies

The transmission of Buddhist teachings through written media was not only shaped by doctrinal needs but also by the material and technological conditions of different historical periods. In the early stages, Buddhist texts were written on perishable materials such as palm leaves and birch bark. Palm-leaf manuscripts, commonly used in South and Southeast Asia, were inscribed using a stylus and then treated with ink or soot to enhance legibility. In Central Asia and northern India, birch bark was sometimes used, though it was more fragile and less durable.

The preparation and copying of manuscripts were labor-intensive and required specialized scribes, often within monastic settings. Texts were typically preserved in manuscript libraries attached to temples or monasteries, though environmental factors like humidity and insects posed continual threats to their longevity.

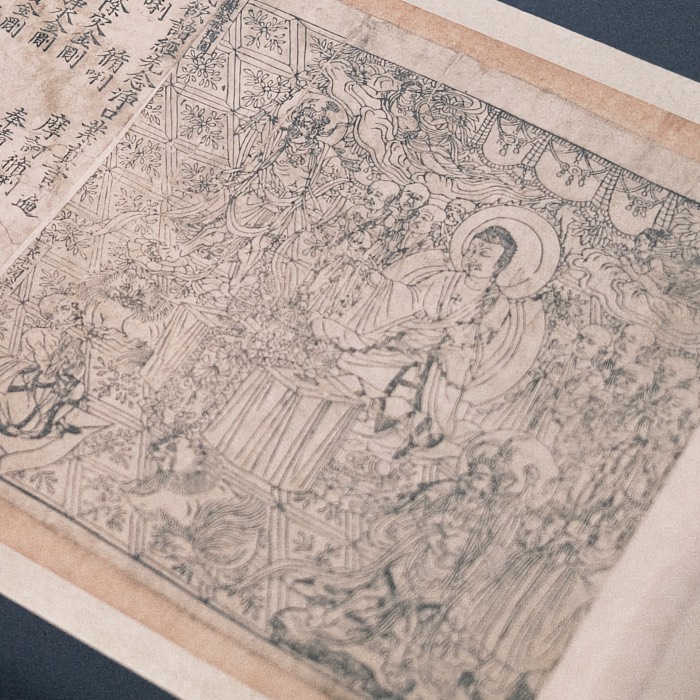

The advent of paper in China during the Han dynasty revolutionized textual production. By the 7th century, Buddhist texts were being reproduced using woodblock printing, making them among the first texts in the world to be mass-produced. The earliest known printed Buddhist text is a Chinese Dhāraṇī scroll dated to 868 CE, known as the Diamond Sūtra, discovered in the Dunhuang cave libraries. This predates Gutenberg’s movable type printing by nearly six centuries.

Korea also made significant contributions to printing technology. As previously noted in the section on the Korean canon, in the 13th century, Korean Buddhists produced the Tripitaka Koreana, a complete woodblock edition of the Buddhist canon carved onto more than 80,000 wooden blocks. It remains a remarkable achievement in both technical execution and textual accuracy. Korea also pioneered the use of movable metal type in the 13th century, further expanding the efficiency of text reproduction.

These advancements in writing materials and printing technologies not only facilitated the preservation and dissemination of Buddhist teachings but also contributed to the broader history of literacy and textual culture in Asia.

Textual criticism and modern scholarship

Modern academic scholarship has approached Buddhist texts with the tools of philology, historical analysis, and textual criticism. By comparing versions across different languages and manuscripts, scholars attempt to reconstruct earlier forms of the texts and understand the processes of redaction and transmission.

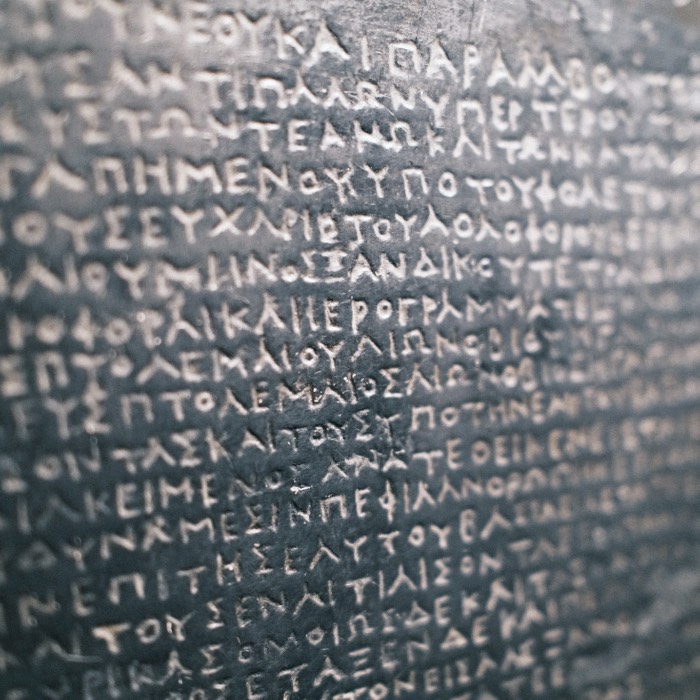

This work has revealed that even foundational texts, such as those in the Pāli Canon or Mahāyāna sutras, are composite and layered. The study of inconsistencies, repetitions, and interpolations provides insight into how communities adapted their teachings over time. Moreover, the discovery of manuscript caches — such as the Gandhāran texts written in Kharosthī — has opened new avenues for understanding the earliest phases of Buddhist writing.

Conclusion

The historical breadth and cultural diversity of Buddhist written sources highlight their significance not only as religious artifacts but as vehicles for the transmission, transformation, and adaptation of ideas across time and geography. From oral transmission rooted in ancient Indian memory practices to large-scale woodblock printing in East Asia, the evolution of Buddhist texts reflects the pragmatic and adaptive character of the tradition. The canonization processes in Pāli, Sanskrit, Chinese, Tibetan, Korean, and Japanese contexts demonstrate both continuity and creative divergence in the preservation of Buddhist doctrine.

Crucially, the Buddhist tradition did not treat textual transmission as inflexible or absolute. While great care was taken to preserve foundational teachings, texts were regularly contextualized, expanded, or newly composed to meet the needs of different communities. This flexibility stands in contrast to many Western religious traditions, where textual fixation and claims of unalterable scripture have often led to rigid orthodoxy. Buddhist textuality, by comparison, is marked by a layered structure that tolerates multiplicity and evolution.

Moreover, Buddhism’s early emphasis on impermanence (anicca), emptiness (śūnyatā), and the limitations of conceptualization arguably fostered a more critical and analytical engagement with its own scriptures. The development of vast commentarial traditions and scholastic reinterpretations is evidence of a culture that values the interrogation of inherited knowledge. In this respect, Buddhism may offer a model of religious literacy that integrates reverence with intellectual openness — a balance often difficult to achieve in Western scriptural traditions.

Ultimately, the written sources of Buddhism are not static repositories of doctrine but dynamic expressions of a living tradition. Their preservation and study continue to offer valuable insights into not only the nature of Buddhism but also broader questions about cultural transmission, textual authority, and the role of writing in shaping religious experience.

References and further readings

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments